Litigiousness, lawyers and Spanish regional differences

Another post on why the Canary Islands are peculiar, while subtly hinting at the implications for understanding Latin America

Some societies are more litigious than others.

Also, some countries have more or less lawyers than others1.

Writing about litigiousness - the American kind in particular - Helle Porsdam tells us2:

It may well be, that is, that the adversarial framework of litigation encourages hostility and competitive aggression at the cost of trust and helpfulness, but it seems, by and large, to be the least harmful and most legitimate means in this democratic and pluralistic day and age of seeking and winning one’s just deserts. Ultimately, the question is not one of either/or - law or no law - but rather one of degree - how much or how many and what kind of law(s)!

I wouldn’t go so far as to assert that there’s a clear relationship between a society’s level of litigiousness and its level of trust, but some research and a few data points suggest that there is such a connection3, and that it could be related to what is known as social capital:

Where the regional culture is one of high cohesion and trust, people may exercise a higher degree of caution and vigilance in their interaction with others, and feel less inclination to file lawsuits subsequent to accidents4.

What I will argue in this post is that some connection exists between litigiousness and culture. Whether a culture leans more (or less) towards violence, litigation, informal arbitration, or any other means to resolve its conflicts reveals something meaningful about that culture.

I want to make this argument specifically for Spanish cultures.

But before diving into Spain and the litigiousness of its various regions, I’d like to first take a look at other nations so we can better understand how litigiousness varies between regions, countries, and even across time.

Let’s start with Japan.

Japanese litigiousness

At first glance, it might be a good idea to compare the level of litigiousness of various societies in order to understand the differences in social capital and level of trust5 among them. Though this might give us some insights into the causes of litigiousness, it wouldn’t be a fair comparison.

Consider Japan, a country famous for its low litigiousness and small number of practicing lawyers, which undertook a number of legal system reforms in the 1990s:

In 1991, an agreement among the three main actors led to a revision of the National Bar Examination Act and a gradual expansion in the size of the bar passage group, combined with a reduction in the term needed to complete the LTRI course…The report calls for expanding the bar to an expected number of 50,000 lawyers by 2018, roughly tripling in 18 years6.

This massive increase in the number of practicing lawyers in Japan clearly shows that other factors beyond culture, such as legal reforms, certainly impact a country’s level of litigiousness.

The paper I just quoted, Ginsburg and Hoetker (2016), finds that the increase in the number of lawyers did lead to higher litigiousness, supporting the notion that there is a relationship, albeit a modest one, between a country’s number of lawyers and its litigiousness:

we see that Japan added 4,030 lawyers between 1986 and 2001. On the basis of the 2001 Japanese population, these lawyers were responsible for approximately 8,622 more new common actions in 2001 (out of a total of 146,113 new common actions that year)7.

While also finding a clear relationship between litigiousness and cultural factors, such as willingness to break commercial relationships:

we also find that change in economic activity over time affects litigation. During downturns in which the prefectural income has declined since the previous year, litigation increases. This is consistent with the literature that finds that litigation is countercyclical, as bad times mean more broken contracts and a willingness to break relationships8.

Yet, to keep things in perspective, even after these reforms, the level of litigation in Japan remains significantly lower than in the (famously litigious?9) United States:

Compared with the United States, the unavailability of punitive damages for many kinds of civil disputes means that attorneys have no positive incentive to seek out plaintiffs. Furthermore, plaintiffs have relatively less incentive to litigate when at best they will be made whole, without the “tort lottery” that allows them to get a share of punitive damages10.

To summarize, the very limited research and data available on this subject suggest what seems to be some relation between number of lawyers in a country and litigiousness in said country, and some relationship between a nation’s culture (social capital) and its level of litigiousness.

Moreover, changes in the number of lawyers may be mediated by shifts in litigiousness, driven by increased or decreased demand for legal services. And conversely, changes in the level of litigiousness may also be mediated by changes in the number of lawyers, due to the elasticity of demand for (cheaper or more expensive) legal services.

I wouldn’t consider the relationship between culture and litigiousness to be firmly established (yet), though. In fact, the reason I’m referencing a paper on Japanese litigiousness is because a large part of the scant research I found on the connection between litigiousness and social trust focuses on Japan.

Now, let’s look at another country.

American litigiousness

Regardless of whether the United States is highly litigious or not, it does provides us with an example of multiple comparable jurisdictions with similar, though not identical, legal systems, and varying levels of litigiousness.

In the case of the U.S., New England states seem to have lower levels of litigiousness compared to most other states, with per capita rates ranging from 10% to 50% below the American median11, yet I haven’t noticed any clear pattern among states with high levels of civil litigation.

The New England pattern appears to hold, albeit less strongly, when looking at family law cases.

This again suggests a connection between culture and litigiousness, as seen in New England, which aligns with the idea that higher litigiousness correlates with lower levels of social trust.

That pattern seems interesting, but unless I can exclude the effect of certain legal principles, such as permitting or banning no-fault divorce, from the state data, there’s not much more I can do with American data.

Let’s now move on to France, Spain’s northern neighbor.

Now French litigiousness

You may have noticed that when exploring litigiousness in the U.S. I left out criminal cases, focusing instead on civil and family law cases.

This is because I want to concentrate on legal cases that I believe more clearly reflect trust and social capital, while omitting legal cases that probably relate to criminality levels (violent or property crime) or driving culture (traffic cases).

The difficulty in omitting those cases lies in the varying ways countries use to classify legal cases. While most countries seem to make a clear distinction between civil and criminal cases12, applying specific filters to a country’s data - such as excluding traffic cases - is not always possible due to the categorization system used by that country.

Why am I complaining about this now? Because the French judicial statistics system, while highly detailed and complete, makes it difficult for me to obtain data directly comparable to the American and Spanish data.

The best I could do was to select the following (first and second level) legal case categories, and assume they adequately represent French civil and family litigation13. WARNING: French legalese follows:

Infractions économiques

Infractions financières (Contrefaçon, etc)

Infraction à la législation du travail

Atteinte à l’environnement

Affaires non pénales (Affairs prud'homales, etc)

Atteinte à la vie privée

Atteinte à la famille

Atteinte à la dignité de la personne (Dénonciation calomnieuse, etc)

While this is not good enough for comparing French litigiousness with other countries14, it’s at least good enough for comparisons across French regions:

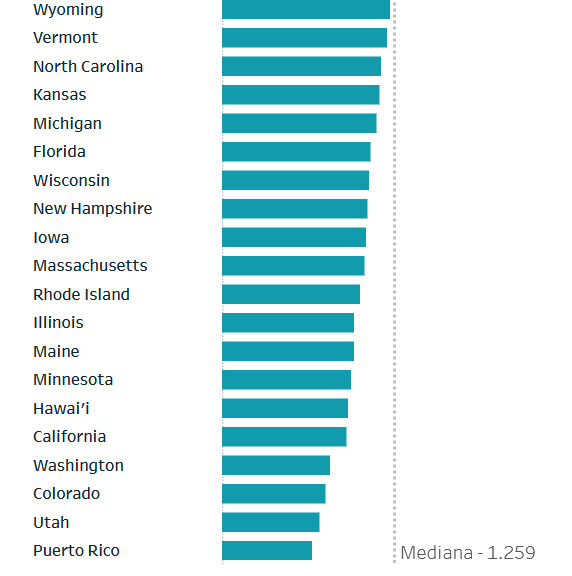

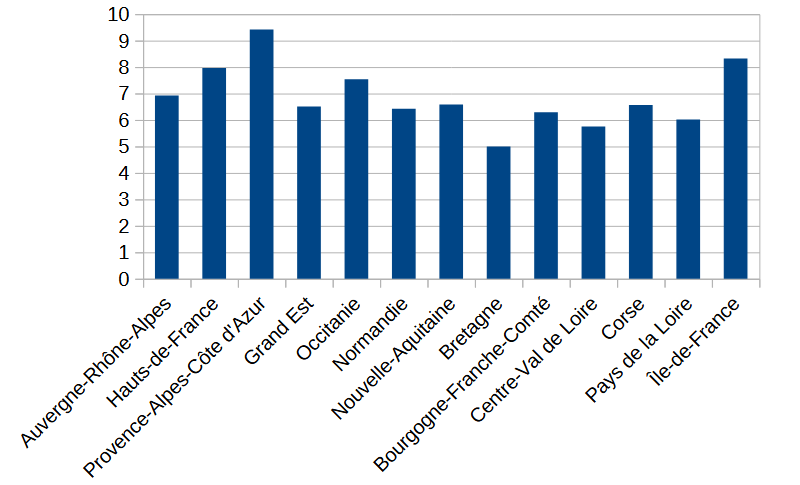

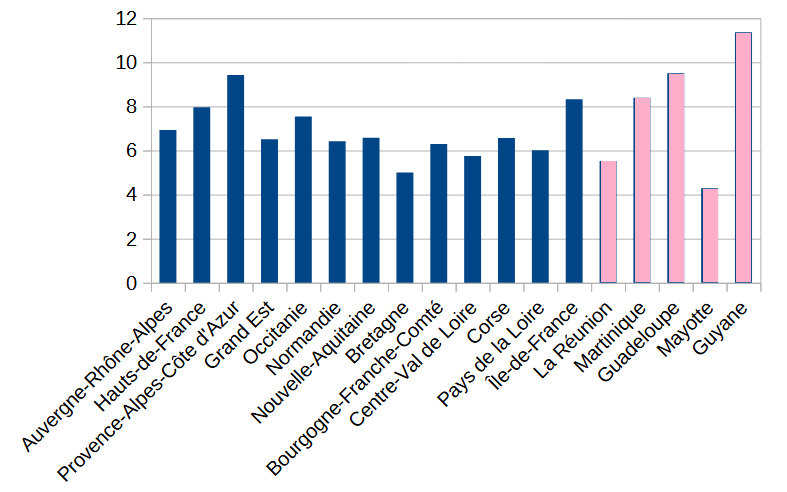

First thing to notice in the above chart is that the French legal system, more homogeneous than the American one, shows less regional variation in litigiousness compared to the stark differences we saw among U.S. states.

Still, France’s most litigious regions, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur with 9.4 cases per 1,000 people Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur and Corsica with litigiousness rates of around 8.8-8.9 cases per 1,000 people, is 88% are 66% more litigious than its least litigious region - Bretagne.

The first and second more litigious regions, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur and Île-de-France15, correspond to the second and first most urbanized regions of France. In fact, the correlation between urbanization rate and litigiousness in France is a very high 0.84 0.66.

UPDATE: Please see my follow-up post, where I’ve corrected some errors in the calculations I made for France.

Can we distill any additional insights from the French data beyond the strong correlation between litigiousness and urbanization?

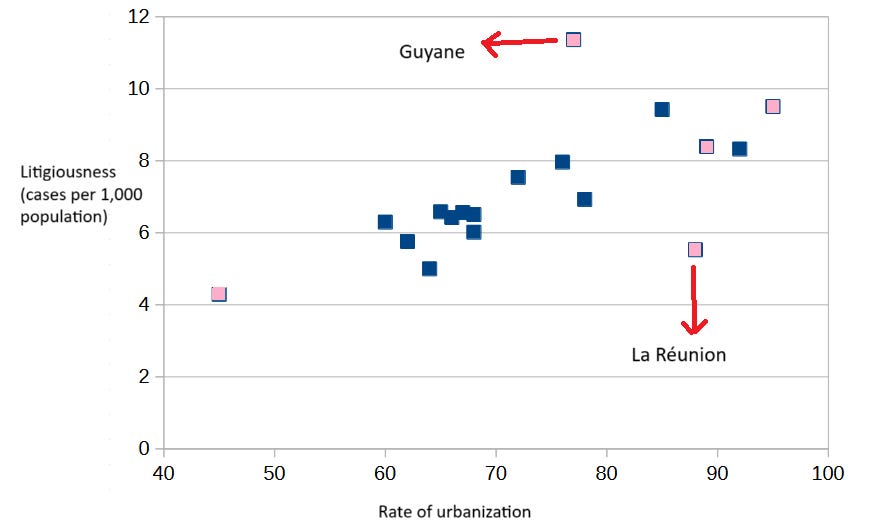

Well, yes. France has five overseas departments and regions, each with its own unique culture, influenced by yet distinct from European French culture.

And it so happens that when I include these five territories in the analysis, it’s now one of them, French Guiana Guadeloupe, that takes the top spot for litigiousness (UPDATE: see fixed chart).

And this time, the degree of urbanization cannot explain the low litigiousness of La Réunion or the high litigiousness of French Guiana Guadeloupe, as shown by the following chart of litigiousness against urbanization rate for each region or territory (UPDATE: see fixed chart):

Which again seems to point to a strong relationship between culture and litigiousness, even when looking at jurisdictions that share the same legal system16.

I should probably look at French data from other years later on (see footnote 16) to better understand the variations in litigiousness in France, but I think I’ve spent enough time on France already, and I should really move on to Spain.

UPDATE: I should do the thing instead of writing that I should probably do the thing!

Finally Spain (and by Spain I really mean the Canary Islands)

The Spanish Wikipedia article on Canarian culture focuses almost exclusively on architecture, painting and sculpture, with no mention of litigiousness, social trust or political culture. If you’ve read my previous posts on the relationship between the Canary Islands and Latin America, you might already suspect this isn’t what I’d usually refer to as Canarian culture.

So, delving into the aspect of culture that I want to explore in this post, what can I say about Canarian litigiousness?

Before I even take a look at the Spanish judicial data, just by reading the press I can say it’s high:

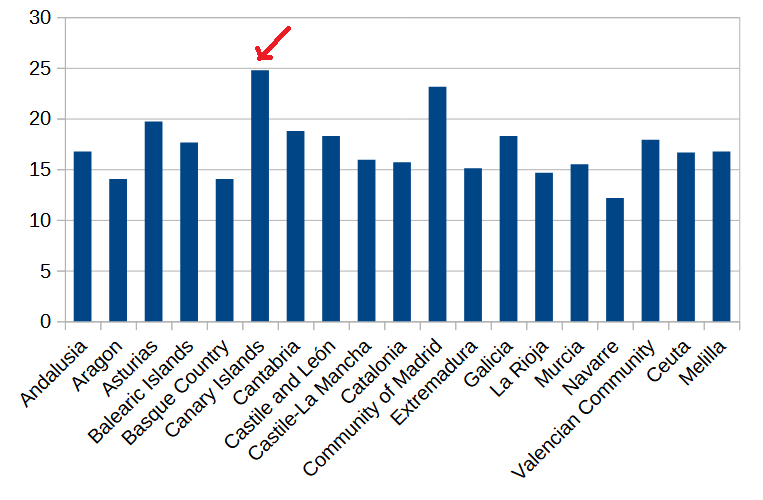

According to the data from the TSJC Report, the Canary Islands are once again, for the fourth consecutive year, the territory in the [Spanish] State where the most litigation took place: 188.67 lawsuits per 1,000 inhabitants, 43.01 more than the State average (145.66) and 31.91 more than the second in the ranking, Andalusia, which recorded 156.76 lawsuits per 1,000 inhabitants17.

The figures mentioned in the media piece I just quoted - The Canary Islands are 30% more litigious than Spain as a whole - should raise some skepticism on your part. The per capita litigiousness rates we just saw, ranging from 4 to 12 cases per 1,000 people in France and averaging around 40 per 1,000 in the United States, are significantly lower than those reported for Spain.

The high figures result from the media piece grouping all cases together: criminal, traffic, labor law, etc18. These are not the numbers I want to review.

Luckily (?), the Spanish judicial authority provides more detailed data; though not disaggregated in the same manner as French or American data, it’s good enough for analyzing and gaining some insights into Spanish litigiousness.

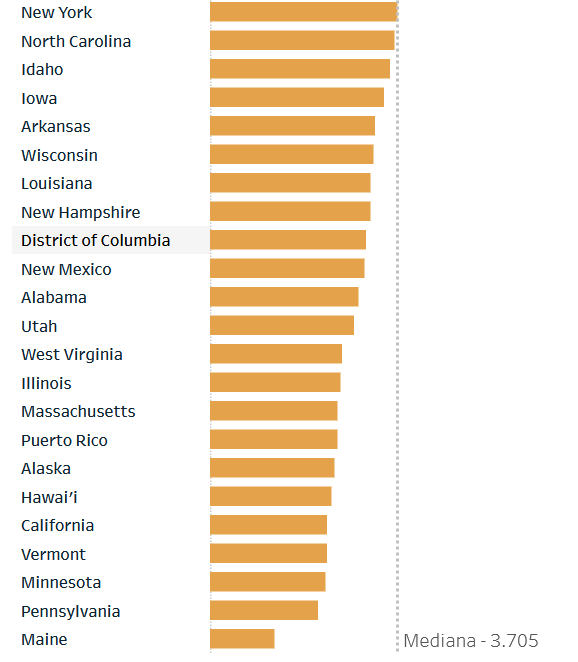

So, here’s a bar chart showing per capita litigiousness for each Spanish region (autonomous community) in 2023, focusing solely on civil and labor19 cases:

No surprises here. The Canary Islands remain Spain’s most litigious region, though its rate is now 38.5% higher than the national rate.

For comparison, France’s most litigious European region, Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, is 32.7% more litigious than France as a whole. So, at first glance, the Canary Islands seem more exceptional than Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur, though not by much.

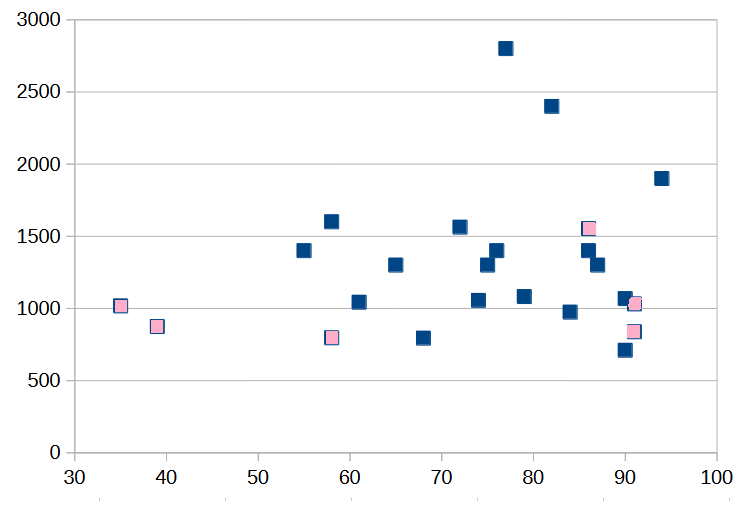

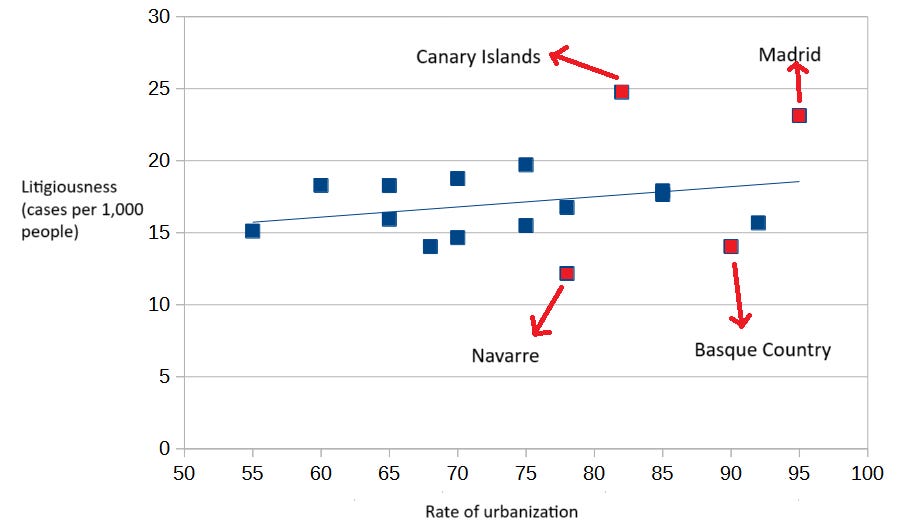

If the correlation between urbanization and litigiousness we observed in France is not spurious20, and urbanization rates indeed help explain variations in litigiousness - when comparing jurisdictions with the same legal system and culture - then it might be interesting to plot litigiousness against urbanization rates for Spanish regions:

A few takeaways from that last chart:

The correlation between urbanization and litigiousness in Spanish regions is much lower than in French regions. Just 0.25 compared with 0.84.

Despite the Canaries being more urbanized than the average Spanish region, the archipelago is still the most significant outlier in terms of litigiousness.

Not surprisingly, Navarre and the Basque Country are also outliers, though due to their low litigiousness.

Could it be that, if litigiousness is related to the number of lawyers, the Canary Islands simply have more lawyers per capita than the rest of Spain?

I can’t find data on this, but it seems highly unlikely. The Canary Islands is one of the poorest regions of Spain, and with no legal barriers to practicing elsewhere in the country, Canarian lawyers actually have a strong economic incentive to leave the archipelago.

I’ve plotted litigiousness against urbanization rates for France and Spain because I believe urbanization explains a large part (most?) of the variation in litigiousness between regions and territories in the absence of significant cultural differences.

Yet I still want to focus on the relationship between culture and litigiousness.

Lacking examples of two or more culturally distant countries with a shared legal system21, the best I can do to test a potential link between culture and litigiousness is to look at places like French Guiana.

And if I can describe French Guiana as culturally distant from European France when measured by its litigiousness level, then I should also be allowed to describe the Canary Islands as fairly distant from Spain on the same measure22.

In fact, excluding the Canaries, Navarre and the Basque Country from the litigiousness versus urbanization plot, on the grounds that they are culturally distant from the rest of Spain, raises the correlation coefficient to 0.4323.

The thing is, no Latin American countries - yes, I was getting to Latin America eventually - derive a large share (say 20% or more) of their Spanish ancestry from the regions of Navarre and the Basque Country24, yet several Latin American countries draw a very large share of their ancestry from the Canary Islands.

This means that, from the point of view of understanding Latin America, its culture, its progress towards development (or lack thereof), and challenges, it seems like a good idea to spend some time trying to understand Canarian culture.

And it also means it might be a good idea to look at whether Canari America, the Latin American countries heavily settled by Canarians, shows some distinctiveness in terms of litigiousness and social trust compared to the rest of the continent, mirroring the Canary Islands’ distinctiveness within Spain.

But that is a subject for another post.

Litigiousness is… something

Is high litigiousness bad? Is it good?

I’ll refrain from judging the merits or faults of litigiousness. If a country, or region, has a culture that predisposes its people toward litigation, I’ll just take that as a given. Different cultures resolve conflicts in different ways.

And it seems to me that Canarian culture is substantially different from Spanish culture.

Maybe Canarians and Guianese are spiteful people with very bad attitudes, harboring grudges left and right, always looking to drag others into a courtroom.

Or perhaps Canarians and Guianese are proud, upstanding people who cherish the law and the functioning of the legal system, and who properly engage the legal system while others, less meticulous and conscientious, would rather look the other way in the face of wrongdoing.

Trust me, it’s something

As I mentioned earlier, some research25 and a few data points suggest that there is a connection between litigiousness and social trust.

And regarding the relationship between social trust and the institutions that typically characterize developed countries, in a 2006 paper published in the journal Kyklos, Berggren and Jordahl conclude that:

On a purely econometric level EFI2 [(Legal structure and security of property rights)] has the largest coefficients in the second column of Table 2 which confirms the relevance of variables such as independence of courts, which Knack and Keefer (1997) find to be strongly related to Trust. Figures 2 and 3 plot Trust against the EFI and against EFI2, in both cases depicting a positive relationship26.

While Zak and Knack (2001), writing about the connection between investment and income on one hand, and trust on the other, state that:

Equation 1 shows that investment is higher where incomes are higher, where investment goods prices are relatively low, and where trust is higher. The investment/GDP share rises by nearly one percentage point for each seven-percentage point increase in trust27.

And even civic participation seems to be correlated to trust:

Controlling for income and education, trust is associated with an 8.6 percentage-point increase in the probability of voting, and with similar increases in interest in political campaigns and in public affairs generally, and with agreement that voting is a civic duty28.

The links between social trust and development seem to be well established in the literature.

These connections between trust and development are what motivates me to explore the subject of litigiousness and how it varies between countries and regions.

Especially if it can help explain Latin America’s underdevelopment.

On a per capita basis, of course.

Take this possible relationship with a big grain of salt. When I asked Grok for help in finding literature on the subject, it came up with four hallucinated papers to help me understand how scarce such literature is.

Think of social trust as just one component of social capital.

“The Unreluctant Litigant? An Empirical Analysis of Japan’s Turn to Litigation”, Tom Ginsburg and Glenn Hoetker, 2016.

“The Unreluctant Litigant? An Empirical Analysis of Japan’s Turn to Litigation”, Tom Ginsburg and Glenn Hoetker, 2016.

“The Unreluctant Litigant? An Empirical Analysis of Japan’s Turn to Litigation”, Tom Ginsburg and Glenn Hoetker, 2016.

There seems to be some true to this assertion. A quick internet search on “famously litigious United States“ returned some results challenging the notion of high American litigiousness, citing sources that claim Germany is the most litigious country in the world. However, official data from German and U.S. sources shows that per the per capita number of civil cases in Germany is around one-fourth of the American rate, at 900 per 100,000 population. This is in line with Germany having a per capita lawyer rate that is roughly half that of the U.S.

“The Unreluctant Litigant? An Empirical Analysis of Japan’s Turn to Litigation”, Tom Ginsburg and Glenn Hoetker, 2016, page 12.

For civil law cases. Rhode Island is an exception, but I understand that Rhode Island is usually regarded as atypical among New England states.

Although Japan apparently doesn’t have separate courts for civil and criminal cases.

The French average, under this definition of “civil and family” cases, is 7.1 new cases per 1,000 population per year (2024).

Île-de-France is actually the Paris region. Apparently, the reason it’s called Île-de-France is because the region’s so full of itself, it thinks it’s an island floating above the rest of France (blame Grok for the bad joke).

The exceptionality of the five overseas departments and regions is clearly confirmed by examining data for 2023, where Mayotte becomes a near outlier and Guadeloupe a clear outlier with litigiousness rates of 5.54 and 14.48 cases per 1,000 respectively. Also, La Réunion with a litigiousness rate of 9.57, is no longer a low-litigiousness outlier, and Guyane (11.58) and Martinique (9.74) remain unchanged.

“Canarias necesita siete juzgados más para afrontar el exceso de litigios”, La Provincia, 24 May 2024.

The article does provide figures for some categories I’m interested in, such as divorces, later in the text: “[In 2023] the civil courts of the Archipelago recorded a total of 5,473 claims for separation, divorce, or annulment of marriage… This represents a rate of 247.3 marriage breakups per 100,000 inhabitants, the highest in Spain during the reference period… The national average was 192.1 marriage breakups per 100,000 inhabitants.”

Labor law cases are labeled as “Jurisdicción social”.

Correlation does not imply causation.

To the best of my knowledge.

Comparing the standardized residuals - from the litigiousness versus urbanization regression - of the Canary Islands (2.27) and French Guiana (2.95) shows French Guiana as a greater outlier in France than the Canary Islands is in Spain, though not by much.

When excluding Catalonia as well, it raises to 0.58.

I’ve mentioned before the overrepresentation of Basques among Latin American elites, and plan to revisit that topic in due course.

See “The Resolution of Karaoke Disputes: The Calculus of Institutions and Social Capital“, Mark D. West (2002): “I look particularly at social capital, borrowing Robert Putnam’s now-standard definition of social capital as ‘features of social organization, such as networks, norms, and trust, that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit.’ In the karaoke dispute context, social capital helps explain why some disputants do not complain even when complaining is free, as well as why counselors often successfully resolve disputes despite their lack of coercive authority“.

Free to Trust: Economic Freedom and Social Capital, Berggren and Jordahl (2006). I don’t agree with the direction of causality proposed by Berggren and Jordahl. They argue that legal structure and security of property rights foster trust, but this contradicts the data for France and Spain that I have presented in this post.

Trust and Growth, Zak and Knack (2001).

Does Social Capital Have an Economic Payoff? A Cross-Country Investigation, Knack and Keefer (1997).