Canari America, the enduring legacy of a Spanish archipelago in the Americas.

How the Fortunate Isles spread their fortune.

According to Kevin Kenny, author of Diaspora: A Very Short Introduction, some 70 million people worldwide claim Irish descent:

From 1700 to the present, fully ten million Irish men, women and children left Ireland and settled abroad. Remarkably, this figure is more than twice the population of the Republic of Ireland today (4.8 million). It exceeds the population of the island of Ireland, north and south (6.6 million). And it is greater than the population of Ireland at its peak in 1845, on the eve of the Famine (8.5 million).1

This small European nation has left an oversized imprint in the populations and cultures of the countries where its people have migrated: America, Canada, Australia.

Bounded by the Irish Sea and the Atlantic Ocean, many Irish people, especially during the 19th century, felt that their only hope for a better life, or even to escape the devastating 1840s famine, was to board a ship and sail towards the setting sun across the ocean.

This is all well known in the English-speaking world. Some countries had a huge role in the settling of the New World, a demographic process triggered by the Age of Discovery, while others had less impact.

Since I’m a numbers guy, I’m not content with knowing the number of people who claim Irish descent. I want a more precise measure of Ireland’s demographic impact on the rest of the world, allowing me to compare Ireland with other countries.

If a Canadian person has only Irish ancestors, I can count that individual as one Irish descendant. If two Australian persons are half Irish - meaning half of their ancestors were Irish - I can count them collectively as one equivalent Irish descendant.

I can assume that most people who claim exclusively Irish ancestry (without any other ancestry) are not fully Irish, but actually half Irish, or three-quarters Irish, or seven-eighths Irish. Assuming that for every person who exclusively claims Irish ancestry, even though they are three-quarters Irish, there is at least another person who non-exclusively claims Irish ancestry and is one-quarter Irish, then simply considering the number of individuals claiming Irish ancestry exclusively should provide a rough estimate of the minimum number of equivalent Irish descendants.2

An alternative approach to estimate the number of equivalent Irish descendants is by taking advantage of the fact that interfaith marriage was not common in the countries settled by the Irish until the 20th century. Assuming that a majority of Catholics were Irish Catholics at a certain point in history, that historical Irish Catholic population can be projected by using a reasonable growth rate to provide an estimate for the present-day equivalent Irish descendants.3

(If you are interested in the specifics of my calculations, you can read the footnotes for a detailed look at my unedited notes.4)

Using the methods I just described, I arrived at an estimate of 30 to 40 million equivalent Irish descendants. Considering the current populations of the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland amount to 6.6 million people5, I estimate the equivalent Irish descendants account for between 4.5X and 6X the population of Ireland.

Although it is a rough estimate, I believe it should be good enough to compare it with an estimate of the number of equivalent Portuguese descendants, which is what I will attempt to do next.

Now let’s do Portugal

The motivations behind Portuguese migration to the Americas differed significantly from those of the Irish. Portuguese migration was largely driven by the dream of striking it rich in the New World, a pull migration, rather than a push migration triggered by the threat of famine.

There’s also the factor of timing. Catholic Irish emigration was predominantly a 19th-century phenomenon, while Portuguese emigration to Brazil was already very significant in the 17th and 18th century. Those who migrated earlier had more descendants than those who migrated later or stayed due to the higher fertility rates among Mestizos and Europeans settled in the Americas compared to those remaining in Europe.

You can think of this phenomenon of compounded natural population growth as similar to compounded interest, producing increasingly larger effects over time. This difference in fertility was such that by the time of Brazil's independence in 1822, the country's population already exceeded that of its mother country Portugal.6

To produce a rough estimate of the number of equivalent Portuguese descendants, I will focus solely on Brazil, treating other migration destinations as minor. But this presents a challenge, as Brazil is a racially fluid country and most Brazilians have mixed ethnic origins.

Here’s where genetics can help us to address this challenge. Genetics studies indicate that approximately 65% of Brazilian ancestry is of European origin.7

Needless to say, European ancestry does not necessarily mean Portuguese ancestry, and around 20% of Brazilians declare one or more European ancestries other than Portuguese.

Assuming 20% of Brazilians translates to 15% of equivalent non-Portuguese descendants, and considering the current Brazilian population of 203 million, the number of equivalent Portuguese descendants in Brazil is 102 million.

Very roughly, the equivalent Portuguese descendants (in Brazil) outnumber those in Portugal by a factor of 10.

If we are ranking European populations in terms of their relative - not absolute - impact outside of their historical land, and assuming this crude demographic measure of equivalent descendants is a valid indicator, then the Portuguese are even more remarkable than the Irish.

But there’s an even more remarkable European population that you might not be familiar with.

Canari America

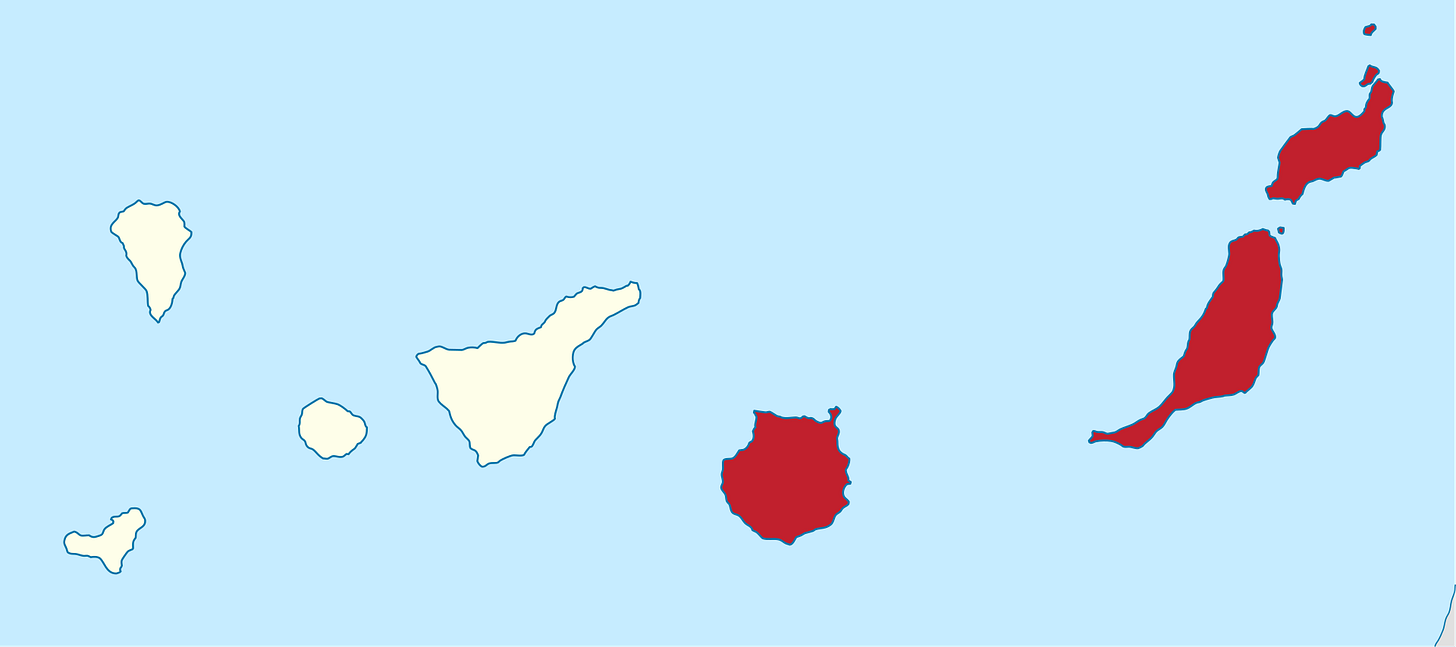

Geographically, the subtropical Spanish archipelago of the Canary Islands can be considered a part of Africa, not Europe, as it is located just 100 km (62 mi) from the African coast, but nearly 940 km (587 mi) from the European mainland.

Being part of the geographical region known as Macaronesia, a group of archipelagos in the North Atlantic Ocean conveniently located on the way from Europe to the Americas, it’s no surprise that its history has been closely tied to the New World.

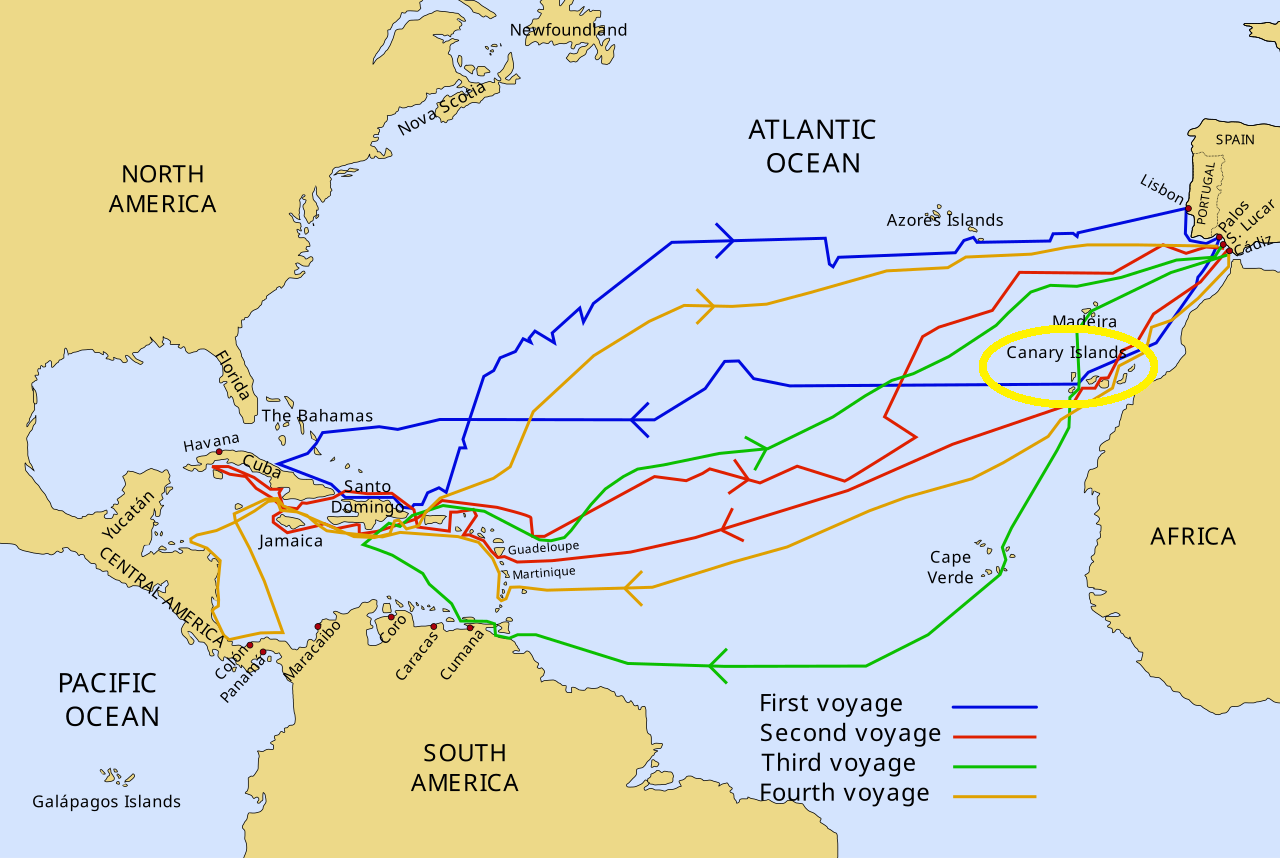

Indeed, on his first voyage to the Americas, Christopher Columbus made a crucial stop in the Canary Islands, which had been conquered by the Spanish during the previous century in a historical process that foreshadowed many aspects of the subsequent conquest of the Americas.

It might seem ironic to the millions of tourists who now flock to the Canary Islands every year, but for several centuries these beautiful subtropical volcanic islands have not been a desirable destination but instead a point of departure for migrants seeking better fortunes across the Atlantic Ocean.

The archipelago's economy, heavily dependent on cash crops like sugar, cochineal, and grapes, was susceptible to the whims of extreme weather and the vagaries of the market. Consequently, each agricultural crisis experienced by the islands resulted in the departure of thousands of Canarians, not to an already densely populated Spain, but to the sparsely populated American continent.

Furthermore, like all Macaronesian islands, the Canaries were formed by volcanic activity8, and they have occasionally experienced episodes of severe destruction, such as the 1730 Timanfaya eruption on the island of Lanzarote:

On September 1, 1730, between nine and ten at night, the earth opened up in Timanfaya, two leagues from Yaiza... and an enormous mountain rose from the bosom of the earth", according to the testimony of the parish priest Lorenzo Curbelo. The island was completely transformed. Nine towns were buried and for six years the lava spread across the southern area covering a quarter of the island and filling the nearby plains with volcanic ash. In 1824 eruptions began again in Timanfaya, giving rise to the so-called Tinguatón, Tao and Fuego volcanoes. Terrible famines occurred and a large part of the population was forced to emigrate.

The fact that the island's climate allowed for the cultivation of tropical crops was a distinct advantage not shared by mainland Spaniards, making emigration to the American tropics, where similar crops could be grown, even more appealing to the islanders.

Additionally, the Canary Islands were the only region of Spain where the Spanish Empire consistently promoted emigration to the new world. Starting in 16789, Canarian traders were required to transport five Canarian families for each 100 tons of cargo shipped to the Americas.

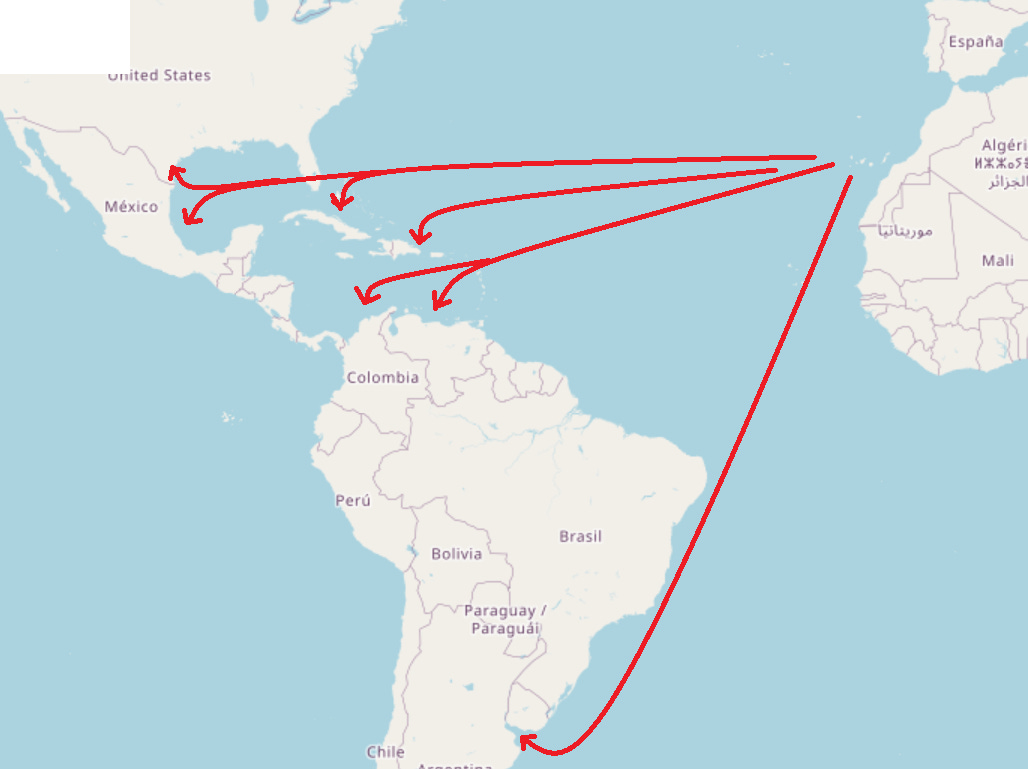

Spanish policy was to settle these emigrants in lightly populated areas of its colonies, such as the Caribbean, Texas (northern Mexico) and the Portuguese-Spanish colonial border (Uruguay), where they could become a bulwark against the encroachment of foreign powers.

Tens of thousands of Canarians emigrated during the 17th and 18th centuries, before the Spanish American wars of independence, settling primarily in the Caribbean. But while Spanish migration to the Americas slowed down considerably after the wars10, Canarian migration in particular, driven by chain migration, continued at a high pace, both to the newly independent Latin American nations and to the colonies of Cuba and Puerto Rico, which remained under Spanish control.

During this 19th-century wave of migration, Canarians predominantly chose Cuba, and particularly Havana, as a destination:11

For the islanders, Havana has become an inexhaustible goldmine that they are exploiting with determination. For the past twenty years, emigration to this land of choice, the sole objective of their desires and the goal of all their dreams, has been constantly increasing…Many of them perish due to the climate, a certain number settle there permanently and others return to the country. Among the latter, some are content to return after having made a few savings; it is true that they return to [Cuba] when their funds have been exhausted.

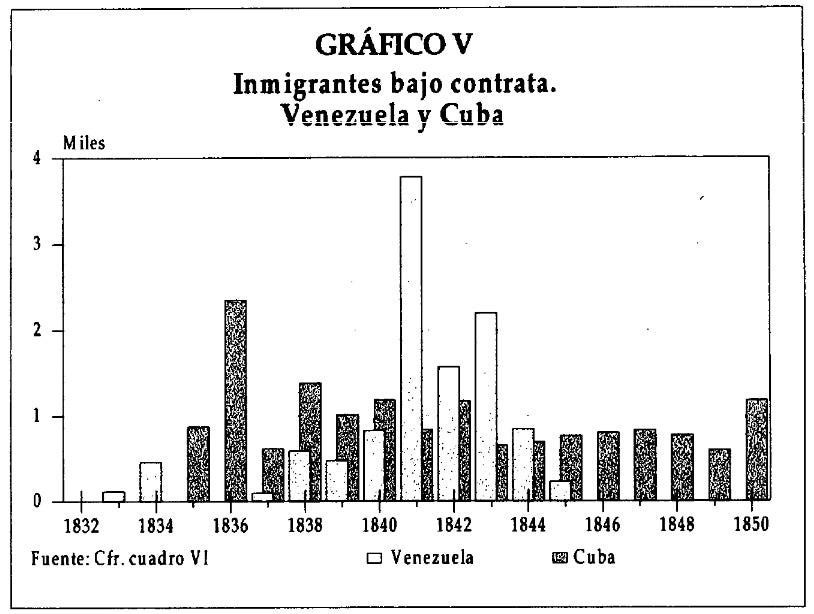

But they also, defying the law if necessary, chose Venezuela as their goal. And the Venezuelan government promoted the migration of Canary Islanders, mostly under work contracts, by subsidizing the cost of transportation.

It is estimated that nearly 20% of the islands' population, approximately 50,000 individuals, migrated to the Americas during the period 1835-1850.12

This wave continued into the late 19th century when other regions of Spain once again became a major source of migrants. Yet the causes of Canarian emigration remained the same:13

From 1871 to 1879, there was no rain on [the Canarian islands of Lanzarote and Fuerteventura]. In the face of this long period of drought, and despite the efforts made not to waste the collected supplies, they were quickly exhausted. Then all the inhabitants were forced to emigrate. I have seen these unfortunate people arrive in Tenerife, almost dead from starvation, taking with them the animals that had survived... A large number of inhabitants emigrated to America at that time, abandoning their homes...

As long as land was plentiful and wages were high in the Americas, emigration remained attractive for the islanders. But the same high Latin American fertility rates that led to a faster growth of the Canarian-descended population in the new world compared to the archipelago, meant that by the early 20th century agricultural land was no longer as plentiful in the new world.

By the 1920s, Canarian emigration to Latin America appeared to be a thing of the past, and it might have ceased entirely had it not been for the discovery of an almost magical substance that makes wages go up: Venezuelan oil.

Between 1950 and 1964, more than 100,000 Canarians14 - approximately a quarter of the population of the Western half of the archipelago15 - migrated to Venezuela, drawn by the economic boom resulting from the transformation of the South American country into one of the world's leading oil producers.

This would be the final wave of Canarian migration to Venezuela, and due to Venezuela's relatively large population of 7 million at the time, it had a much smaller impact on Venezuela's current population than previous waves.

So, what was the cumulative impact of all those waves of Canarian migration to Latin America?

To answer that question, I have to go back to the 15th century Spanish conquest of the Canary Islands.

The conquest was brutal, and the indigenous population of the islands was largely replaced by Spaniards - from Andalusia and Galicia mostly - and Portuguese16 settlers. Largely, but not entirely.

Around 20% of the genes of modern Canary Islanders can be traced back to the original inhabitants of the archipelago, the Guanches. They migrated from the nearby North African coast17, and unsurprisingly, were closely related to the Berber population of North Africa.

Fortunately, this means that certain genetic lineages (maternal mtDNA haplogroups and paternal Y-chromosome haplogroups) are distinctly Guanche18, allowing me to estimate (albeit very roughly) the proportion of Canarian lineages in a population partially descended from Canarians by comparing the prevalence of these lineages in that population with their prevalence in the Canarian population.19

Unfortunately though, I couldn’t find such a study for Venezuela.

But I did find a list of common Venezuelan surnames20, and took advantage of the fact that many Canarian surnames are specific to the Canary Islands and rarely occur in Spain outside of the archipelago to roughly estimate the proportion of European ancestry that is specifically Canarian.21

The Canarian proportion for Venezuela is lower than the one I estimated for Cuba (45%)22, but still accounts for an impressive 40% of all European ancestry.

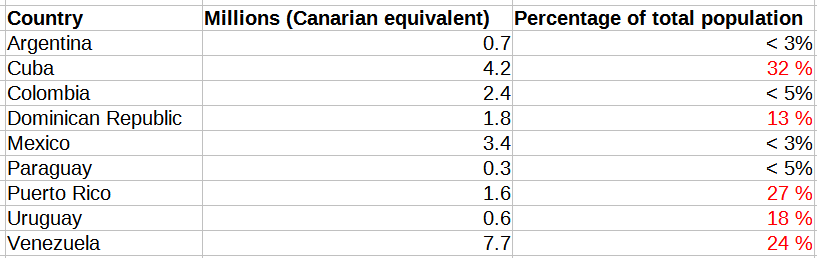

Based on that 40% estimate23, there are approximately 7.7 million equivalent Canarian descendants in Venezuela24, accounting for a quarter of the country's total population.

Cuba, whose total population amounts to 13 million compared to Venezuela's 32 million, has approximately 4.2 million equivalent Canarian descendants, which constitutes a third of Cuba’s total population.

I made similar estimations for Argentina25, Colombia26, the Dominican Republic27, Mexico28, Paraguay29, Puerto Rico30 and Uruguay31 to calculate a total for all of Latin America:

The combined total of equivalent Canarian descendants in those nine countries is 22.7 million people. This new world population of Canarian descent outnumbers the current native32 population of the Canary Islands by a factor of 14.

And while 22 million might seem like a small number compared to the over 400 million people who now live in Latin America (excluding Brazil), they played a significant role in shaping the contemporary societies of a few countries: Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

I doubt there’s any other well-defined region of the world that has had such a large demographic impact outside of its original borders in the last few centuries.

And this demographic impact was accompanied by a not less significant cultural impact, which I plan to discuss in future posts.

(UPDATE: I wrote a couple of additional Canari America posts discussing Venezuela and Colombia.)

This only makes sense when a population has not experienced significant intermarriage. The more ancestries a person has, the less likely that she will report all of those ancestries. And as time passes, there's an increasing tendency for people to identify with more general ancestries, such as “American”, “Australian”, or “Canadian”.

I’m aware that this last approach is useless when estimating the number of descendants of Irish Protestants. However, I did try to include Protestants (Scotch-Irish) in my rough estimate for the U.S.

The UK: Assuming 1961 Irish descended population in Great Britain (not UK) was entirely Catholic, and Catholics were (almost) entirely of Irish descent, and considering the 3.5 million Catholics in Great Britain at the time (https://www.drgareth.info/CathStat.pdf), and growth from 52 million (assuming all white) UK population in 1961 to 55.5 million white UK population today, that makes a total of 3.7 Irish-equivalent people in Great Britain. The U.S.: Self-declared in 2020: 10.9 million (only one ancestry; 30 million multiple). 40 million self-declared in 1980 excluding Scotch-Irish? (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irish_Americans#From_the_17th_century_to_the_mid-19th_century).

306,000 (190 prot and 116 cath) in 1790 census, making them 9.6% of total white pop. Maybe 10X from 1790 to 1900? (that would mean for all Irish old stock, 3 million in 1900). If only Catholic, in 1900 14% of total population was catholic (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Religion_in_the_United_States#Statistics), assuming half were Irish Catholic, that makes 5.3 million Irish Catholics, or 14.8 million Irish Catholics today (ignoring 20th century European migration and 20th century Irish migration). Maybe between 20 and 25 million in total. Australia: 10% of all pop, so 2.4 million self-declared (only one declared ancestry). Also, 921,000 Catholics in 1911 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1911_Australian_census#Religion). Assuming almost all of them were Irish, and population tripled from 1911 to 2024, that’s approximately 2.4 to 2.7 million. Canada: between 4 and 6 million (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irish_Canadians). New Zealand: 0.8 million? (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Irish_New_Zealanders). All together (US + ANZAC + UK), low estimate 30 million. High estimate 40 million.

Actually, it’s more like 7 million. I assume Kevin Kenny uses this number as the total of ethnic Irish in Ireland, which makes sense for the purpose of this post.

Not all immigrants arrived willingly in Brazil. Millions of slaves were forcibly transported from Africa, contributing significantly to the country’s demographic growth.

“O impacto das migrações na constituição genética de populações latino-americanas“, Neide Maria de Oliveira Godinho (2008), https://web.archive.org/web/20160416095955/http://repositorio.unb.br/bitstream/10482/5542/1/2008_NeideMOGodinho.pdf

Indeed, the Teide volcano, located on the Canarian island of Tenerife, is the highest mountain in all of Spain.

This was partially due to a ban on emigration to the new American nations, which was lifted in 1853.

“Historia natural de las Islas Canarias, Geografía descriptiva”, Sabin Berthelot, quoted in “Viajeros del siglo XIX en Canarias“.

"Canarias-Venezuela. Política inmigratoria y migración isleña (1831-1859)", Antonio M. Macías Hernandez, page 50.

“Cinco años de estancia en las Islas Canarias”, René Verneau, quoted in “Viajeros del siglo XIX en Canarias“.

Yes, I know. No, I’m not going to adjust my estimates. These are rough estimates.

The date of their arrival is a subject of debate. Previously, it was believed to have occurred during the first half of the first millennium BC, but a recent study has dated the arrival of the Guanches to the 1st to 3rd centuries AD.

“Demographic history of Canary Islands male gene-pool: replacement of native lineages by European“, R Fregel, V Gomes (2009).

Assuming that the ratio of Canarian women to all European women immigrants is the same as the ratio of Canarian men to all European men immigrants.

I validated this estimate against those of other Latin American countries where genetic studies and surnames lists were available.

My unedited notes for how I calculated that 45% for Cuba: From “Genetic origin, admixture, and asymmetry in maternal and paternal human lineages in Cuba“, on Cuban mtDNA: “Within the African lineages, the vast majority of sequences belong to sub-Saharan L haplogroups (43.3% of the total sample), whereas a small proportion (2% of the total sample) fall into the typical North African U6 haplogroup. Interestingly, most of these U6 sequences belong to the sub-clade U6b1, which is characteristic of Canary Islands. The main U6b1 profile A16163G T16172C A16219G T16311C (three matches in Cuba) is in fact highly prevalent in the Canary Islands (~10%), and outside these islands, it appears only sporadically in some other Latin-American countries such as Uruguay“. The characteristically North African U6 (some lineages are only found in the Canaries) is 9.4% of West Eurasian mtDNA haplogroups in Cuba (https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1471-2148-8-213), while it’s 21.1% of indigenous haplogroups in the Canaries (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6426200/). That suggests a little less than half (45%) of all female European - or West Eurasian more generally - ancestors of Cuban being Canary Islanders. “An autosomal study from 2014 found the genetic ancestry in Cuba to be 72% European, 20% African and 8% Amerindian“ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cubans#Genetics). Cuban Y-haplogroups: 6.1% for E1b1b-M81, 8.3% for I, 50.8% for R1b (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_Cuba#Y-DNA). In modern Canary Islanders E1b1b-M81 is around 11-13%. The indigenous (Guanche) Y-haplogroups share in modern Canary Islanders is so low (16%?) that it doesn’t make much sense to try estimate the Canarian share in Cuba based on Cuban Y-haplogroups (though it fits with around 50% Canarian).. If 45% of Cuba’s European ancestry is Canarian, and 72% of ancestry is European, that suggests 4.2 million Canarian-equivalent descendants.

My unedited notes for how I calculated the 7.7 million for Venezuela: Brazilian study (which says PR is 60% when it’s really 66%, seems to systematically report lower) says Venezuela has 60.6% European ancestry (https://web.archive.org/web/20160416095955/http://repositorio.unb.br/bitstream/10482/5542/1/2008_NeideMOGodinho.pdf). Very rough (average of low socioeconomic and high socioeconomic levels) estimate for Venezuela (Caracas) is 60% European (https://bioone.org/journals/human-biology/volume-79/issue-2/hub.2007.0032/Admixture-Estimates-for-Caracas-Venezuela-Based-on-Autosomal-Y-Chromosome/10.1353/hub.2007.0032.short). Canarian ancestry in Venezuela seems to be a little lower than in Cuba (can’t find mtDNA studies for Venezuela, but surname analysis says Venezuela is a little less 50% vs 52.8% Canarian than Cuba). Assuming it’s 40%, and 60% of Venezuelan ancestry is European, that suggests 7.7 million Canarian-equivalent descendants.

Including the Venezuelan diaspora. All estimations of equivalent Canarian descendants were made including the diapora of each country (Mexico, Puerto Rico, Cuba, Dominican Republic).

My unedited notes for Argentina: 2 out of 214 West Eurasian mtDNA lineages for Argentina are U6 (https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/1471-2156-12-77#MOESM1), characteristically Canarian, while it’s 21.1% of indigenous haplogroups in the Canaries (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6426200/). That suggests 4.3% of all female European - or West Eurasian more generally - ancestors of Argentines being Canary Islanders. Since those Canary Islanders arrived before the massive European migrations of the late 19th century (which were skewed male), I’ll assume only 2% of European Argentine ancestry is Canary Islander. Assuming European ancestry in Argentina is 75%, and 2% of that ancestry is Canarian, that suggests 0.7 million Canarian-equivalent descendants.

My unedited notes for Colombia: If 10% of Colombia’s European ancestry is Canarian (Atlantic region population is 25% of the total), and 46% of ancestry is European (https://web.archive.org/web/20160416095955/http://repositorio.unb.br/bitstream/10482/5542/1/2008_NeideMOGodinho.pdf), that suggests 2.4 million Canarian-equivalent descendants.

My unedited notes for the Dominican Republic: From “Y Haplogroup Diversity of the Dominican Republic“ (https://academic.oup.com/gbe/article/12/9/1579/5896526), 2.6% of paternal lineages in the DR are E1b1b-M81. Considering that 8.3% of paternal lineages in the Canaries are E1b1b-M81, that suggests 31.3% of all male European - or West Eurasian more generally - ancestors of Dominicans being Canary Islanders. I’ll use 30% as the percentage of Canarian ancestry among European ancestry. “The average admixture of founder Dominican population was 73% European, 10% Native, and 17% African, but due to transatlantic slave trade, and migration from Haiti and Afro-Caribbean countries, the current overall admixture is 47%-57% European, 8%-12% Native and 35%-42% African“ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/People_of_the_Dominican_Republic#Genetics_and_ethnicities). If European ancestry in the Dominican Republic is 50%, and 30% of that ancestry is Canarian, that suggests 2.1 million Canarian-equivalent descendants.

My unedited notes for Mexico: 3 out of 2021 mtDNA lineages are U6 (https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4425/12/9/1453; table S5), characteristically Canarian. Since 8% of all mtDNA lineages are West Eurasian, that means 1.85% of all Eurasian lineages are Canarian. That suggests 8.8% of all female European - or West Eurasian more generally - ancestors of Mexicans being Canary Islanders. 2 out of 131 paternal lineages in Mexico are E1b1b-M81 (or subclade M183). Considering that 8.3% of paternal lineages in the Canaries are E1b1b-M81, that suggests 1.8% of all male European - or West Eurasian more generally - ancestors of Mexicans being Canary Islanders. Source: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/suppl/10.1080/19485565.2015.1117938?scroll=top. If 5% of Mexico’s European ancestry is Canarian, and 45% of ancestry is European, that suggests 3.4 million Canarian-equivalent descendants.

My unedited notes for Paraguay: “The Ancestry of Eastern Paraguay: A Typical South American Profile with a Unique Pattern of Admixture“: “The ancestry proportions obtained were as follows: 55.4% European, 33.8% Native American and 10.8% African” (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8625094/; https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4425/12/11/1788). No haplogroups studies, so using surname estimates. If 10% of Paraguay’s European ancestry is Canarian, and 55.4% of ancestry is European, that suggests 0.3 million Canarian-equivalent descendants.

My unedited notes for Puerto Rico: “The average genomewide individual ancestry proportions have been estimated as .66, .18, and .16, for European, West African, and Native American, respectively” (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1950843/). 3 out of 18 West Eurasian mtDNA lineages for Puerto Rico are U6 (https://sci-hub.ru/10.1002/ajpa.20108), characteristically Canarian, while it’s 21.1% of indigenous haplogroups in the Canaries (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6426200/). That suggests 79.1% of all female European - or West Eurasian more generally - ancestors of Puerto Ricans being Canary Islanders. That seems way too high. Also: “Our study shows that up to 38% of West Eurasian and North African mitochondrial ancestry in Puerto Rico most likely migrated from the Canary Islands.“ (https://bioone.org/journals/human-biology/volume-89/issue-2/humanbiology.89.2.04/A-Mainly-Circum-Mediterranean-Origin-for-West-Eurasian-and-North/10.13110/humanbiology.89.2.04.short). From “Y Haplogroup Diversity of the Dominican Republic“ (https://academic.oup.com/gbe/article/12/9/1579/5896526), 5.6% of paternal lineages in Puerto Rico are E1b1b-M81. Considering that 8.3% of paternal lineages in the Canaries are E1b1b-M81, that suggests 67.5% of all male European - or West Eurasian more generally - ancestors of Puerto Ricans being Canary Islanders. If European ancestry in Puerto Rico is 66%, and 40% of that ancestry is Canarian, that suggests 1.4 million Canarian-equivalent descendants.

My unedited notes for Uruguay: “Haplogroup U6 has a unique distribution, being found primarily in North Africa and the Canary Islands (Pereira et al., 2010). Its presence in Uruguay“ (https://sci-hub.ru/10.1002/ajhb.22667). 2 out of the 30 West Eurasian mtDNA lineages for Uruguay are U6, characteristically Canarian, while it’s 21.1% for the indigenous haplogroups in the Canaries (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6426200/). That suggests a little less than half (47.4%) of all female European - or West Eurasian more generally - ancestors of Uruguayans being Canary Islanders. It’s probably too high (small town in northern Uruguay). But, maybe 30% is reasonable. Assuming European ancestry in Uruguay is 75% (same as Argentina), and 30% of that ancestry is Canarian, that suggests 0.6 million Canarian-equivalent descendants.

As of 2019, 28% of the 2.2 million population of the Canary Islands was not born in the archipelago.

Your article is fascinating. Thank you for reading my post. If you scroll down the page to the update from March 14th, 2019, I mention that I think it’s a mistake to take these estimates from ADMIXTURE too literally for several reasons, which I addressed there in more detail. There are caveats to most “prepackaged” statistical software in population genetics which, I think, are important to consider when trying to interpret admixture results.

In my view, it’s difficult (if not impossible in some cases) to use autosomal DNA to clearly differentiate between present-day groups which already share a significant degree of ancient genetic proximity. Furthermore, in this case, an adequate dataset should ideally include ancient Canarian samples that are representative of all the Canarian Islands and not just North African samples to be used as proxies for Guanche DNA. This is because meaningful genetic variations between ancient Canarian samples & present-day North Africans were observed in a recent paper from Serrano et al (2023). It’s called “The genomic history of the indigenous people of the Canary Islands.” In the paper, the authors analyzed ancient Canarian samples from individuals that are estimated to have lived from the 3rd to the 16th century. See this link: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-023-40198-w

This is why I think this topic as it relates to genetics should be further investigated and corroborated with more diversified analyses before reaching a definitive conclusion.

Hi there. This was very interesting but I have some caveats re. your historical approach. Why? Because, some years ago, an acquaintance of mine, Thierno (with my help but it was mostly his work) made a mini-study on actual genetic ancestry of Puerto Ricans and the actual results, which you can read here: https://forwhattheywereweare.blogspot.com/2018/10/the-major-guanche-genetic-influence-in.html (my old blog), show that every single Puerto Rican has some Guanche (Berber, the proxies were Moroccans and Sahrawis, the latter being probably more representative) ancestry, what is only logical if you consider that people do admix every generation. The average Guanche ancestry is in the ballpark of 40-50%.

Comparing your estimates and Thierno's, I think I can give a rough estimate of the likely Guanche ancestry in the Caribbean countries you considered (Central America should have also been affected):

Puerto Rico: 45%

Cuba: 53%

Dominican Rep.: 22%

Venezuela: 40%

Colombia: 8% ?

Mexico: 5% ?

Another caveat I have is about the "colonialist" (benevolent) narrative you spouse for this major migration: the anticolonialist narrative, which is, as usual hidden under the rug, talks of "Tributo de Sangre" (Blood Tax) and forced displacement of poorer (and typically more aboriginal) Canarians to the Caribbean and not by choice. The exact method varied through the centuries but it was very persistent.