Canarian religious culture in the Americas

What does religiosity tell us about the Spanish Caribbean

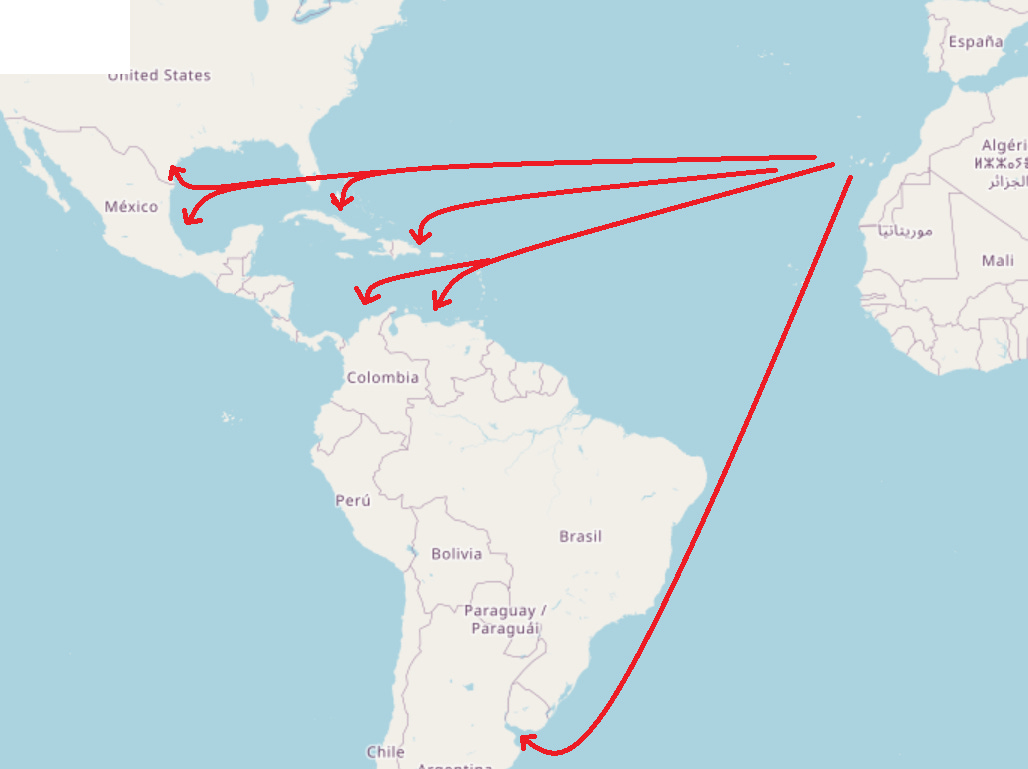

I’ve previously written about the cultural variances across different regions of Latin America, and how those differences could arise from distinct migration flows, originating in various regions of Spain, that colonized what are now separate Latin American countries or regions.

In particular, I explored the differences between the Andean region of Venezuela and Coastal Venezuela from the point of view of political culture:

And I linked those differences to the significant migration of Canarians to Coastal Caribbean Venezuela and other parts of the Caribbean, contrasting this with the relatively lower level of Canarian migration to the Andean region of Venezuela.

I now want to explore the Canarian legacy in Latin America from another angle: that of religious culture.

Measuring religiosity

When it comes to religion, assessing differences in religiosity among populations is challenging. Should we just ask people how religious they think they are? Self-reporting can produce misleading and inconsistent results, and so researchers often resort to surveys that ask quantitative questions, such as the frequency of attendance to religious services and the frequency of prayer.

But even those objective questions are influenced by the specifics of religious practices across different religions (such as the prescribed frequency of daily prayers). Moreover, since surveys are a relatively modern tool, we can’t look at old surveys that could tell us about the religiosity of populations from many decades ago.

Therefore, I decided to use an alternative measure of religiosity, one which is very objective and allows for analysis over a broader historical span, rather than being limited to recent decades.

Allow me to introduce you to Catholic-Hierarchy.org, a website dedicated to collecting and cataloging both current and historical information about the bishops and dioceses of the Catholic Church’s hierarchy.

This website has collated a very interesting metric for every Catholic diocese in the world: the ratio of Catholics per priest1. This indicator is calculated by dividing the Catholic population of a diocese by the number of priests (diocesan or religious) in that same diocese.

Is the Catholics per priest (CPP) ratio for a diocese a good measure of the religiosity of that diocese’s flock?

I’ll skip this question for the time being. For now, suffice to say that it is an objective, not self-reported, metric.

We really didn’t like opium anyway

One important factor to take into account when assessing the religiosity of a population is the effect of top-down or governmental policies. Are religious practices being suppressed by the civil authorities? Does the local government expel or repress the clergy that leads religious life?

Such top-down policies can influence the Catholics per priest (CPP) ratio for a country, thus compromising this metric’s reliability as an accurate indicator of a population’s religiosity.

When analyzing how religious culture varies between Latin American countries, the only nation where the distorting effect of religious repression on the CPP ratio significantly worries me is Cuba.

The tropical island nation experienced religious repression beginning in 19592, following the Cuban Revolution. So, in order to avoid the effects of the revolution on Cuban religious culture and on Cuba’s CPP, I’ll examine religiosity within Cuba, and across Latin America, before 19593.

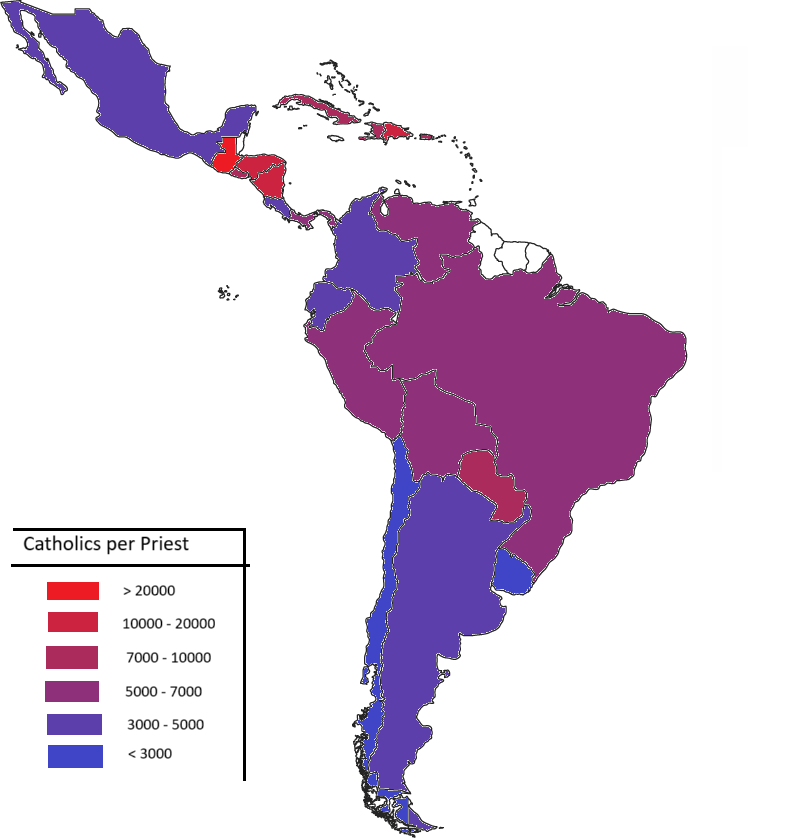

Here’s a color-coded map illustrating the Catholics per priest ratio for each Latin American country in 1950:

Red represents the highest CPP values, meaning a high number of Catholics for each priest. Blue represents the lowest CPP values, signifying a low number of Catholics for each Catholic priest.

For now, I’ll ask you to trust my interpretation of lower CPP as indicating greater religiosity (blue on the map), while a higher CPP implies less religiosity (red on the map).

A CPP of 22,815, as seen in Guatemala (the highest in Latin America for 1950), means that on average each Catholic priest has to care for more than 22,000 parishioners. While a CPP of 2,696, like that of Uruguay, means that each priest is responsible for the spiritual care of less than 3,000 Catholics.

Uruguayan Catholics “consumed” considerably more religious services, as provided by priests in 1950, than Guatemalans did4.

The above map shows that, relatively speaking, Central American Catholics - with the exception of Costa Ricans and Panamanians - were the less religious of all Latin Americans. Conversely, the inhabitants of the Southern Cone of South America were the most religious5 - with the exception of Paraguay.

It also reveals the Caribbean region as particularly irreligious within Latin America. For Latin America as a whole there are 5,159 Catholics per priest, whereas the four Hispanic Caribbean nations average a much higher CPP ratio of 8,324.

The four Hispanic Caribbean countries I am discussing are Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and Venezuela. Collectively, these are what I have previously referred to as Canari America.

Regarding Cuba (with a CPP of 7,189), I can assert with confidence that, even before religion was declared to be the opium of the people, it was not a particularly religious country.

Having said that, Caribbean nations don’t appear particularly irreligious either, at least compared with Andean countries (Peru and Bolivia) and the aforementioned four Central American countries.

If I’m trying to persuade you that Caribbean countries, which received a large demographic input from the Canary Islands during their colonization, are remarkably less religious than their Latin American counterparts due to this Canarian heritage, I should present more evidence to back this claim.

For now, I will sidestep the issue of the Central American and Andean countries to focus on why I believe the (presumed) lower levels of religiosity in the Hispanic Caribbean are related to its Canarian heritage.

The mother nation(s)

Spain is one of the most diverse nations in Europe. Thanks to its expansive territory, being the fourth largest country in the continent, it harbors a multitude of unique regional identities.

How do these regional cultures vary in their religiosity?

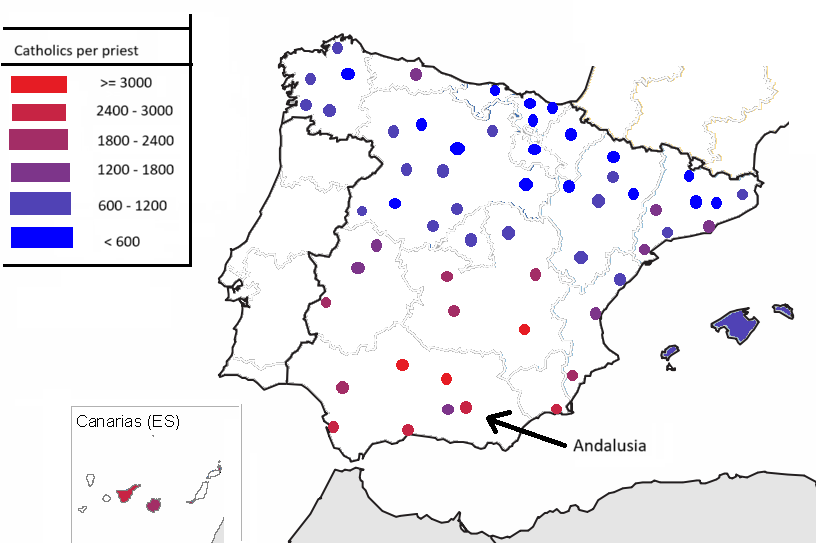

The following is a map of Spain showing the Catholics per priest ratio for all Spanish dioceses in 1950:

It’s quite evident that Southern Spain - particularly Andalusia, along with the Canary Islands - is less religious than Northern Spain. Moreover, it’s also clear by looking at the dioceses in Catalonia and Eastern Aragon (Northeastern Spain) that this disparity is not simply a consequence of the anticlericalism from the Republican side during the Spanish Civil War6.

The distinctiveness of the Canary Islands is corroborated when looking at post-1950 data. By 1970, the archipelago’s CPP was approximately 20% higher than that of Andalusia7.

Given my interpretation that a higher CPP means lower religiosity, the Canary Islands is likely the less religious region of Spain.

Assuming that Hispanic Caribbean religiosity is remarkably low compared to the rest of Latin America - which I haven’t fully proved yet - it seems logical to infer this is not accidental. The region of Spain from which a large part, if not the majority, of the European ancestors of Caribbean Latin Americans originated is also characterized by its low, perhaps the lowest, levels of religiosity in the mother country.

Having journeyed across the ocean to the Iberian Peninsula, let’s examine the religiosity of Portugal, Spain’s neighbor, before we return to the Americas.

In 1950, Portugal had a ratio of 1,511 Catholics per priest, about 50% higher than that of Spain at the time, and intermediate between the ratios for the Spanish regions of Extremadura and Valencia8.

On the other side of the Atlantic, Brazil, predominantly populated by descendants of Portuguese, showed a significantly higher ratio of Catholics per priest at 6,479, compared to the 4,734 in the rest of (Spanish) Latin America, mirroring the disparity observed between Portugal and Spain.

Since I want to highlight the uniqueness of the Canarian regions within Spanish America, in contrast with areas where Canarian colonization was small or insignificant9, I will exclude Portuguese-America, namely Brazil, from the remainder of this analysis.

Back to Latin (Spanish) America

Some Hispanic countries of Latin America are more Hispanic than others. Although migration from Spain to its colonies was widely diffused before the Wars of Independence in the early 19th century, the following century saw a more focused flow of Spanish migrants into certain regions of the continent, resulting in a more varied demographic landscape where, beyond the mestizo population at the core of Latin American societies, some populations shifted further towards their Spanish roots (Argentina, Cuba, Uruguay, etc.), while others remained close to their Indigenous American origins10.

Among the latter, Guatemala, along with its eastern neighbors, as well as Bolivia and Peru, display significantly less Spanish ancestry compared to the rest of Latin America11.

To assess the specific impact of Canarian heritage on Latin American religious culture, as opposed to other regional Spanish heritages (like Andalusian, Basque, Castilian, etc.) in the former Spanish colonies, I will exclude from this analysis the aforementioned countries12 where overall Spanish ancestry - from any region of the mother country - is not predominant.

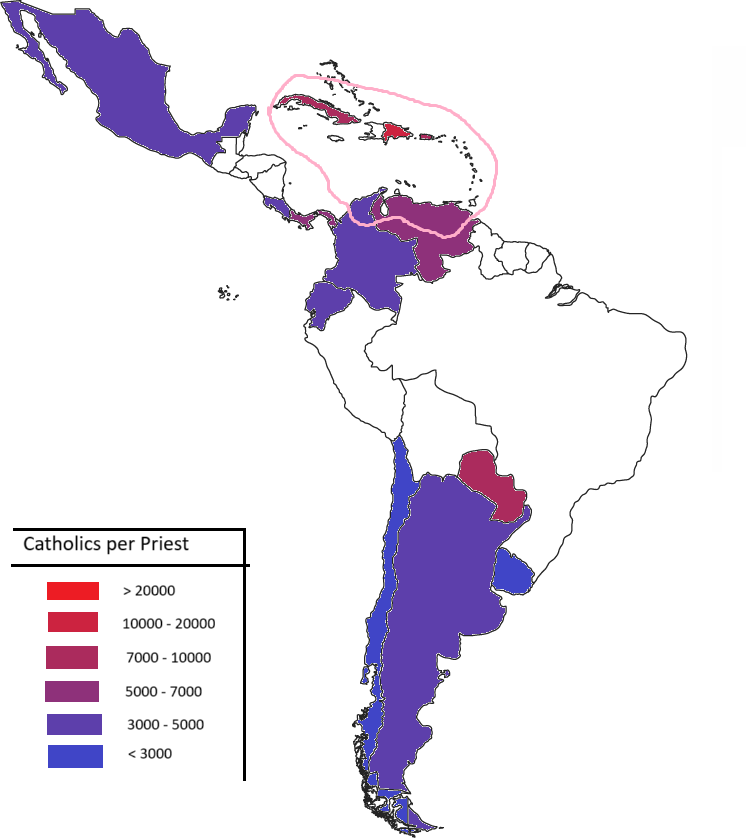

With this in mind, the earlier map showing the ratio of Catholics per priest in Latin America can now be updated:

Now that I’ve removed the less Hispanic countries, the contrast between the four Caribbean countries and the rest of (predominantly Hispanic) Latin America becomes clearer.

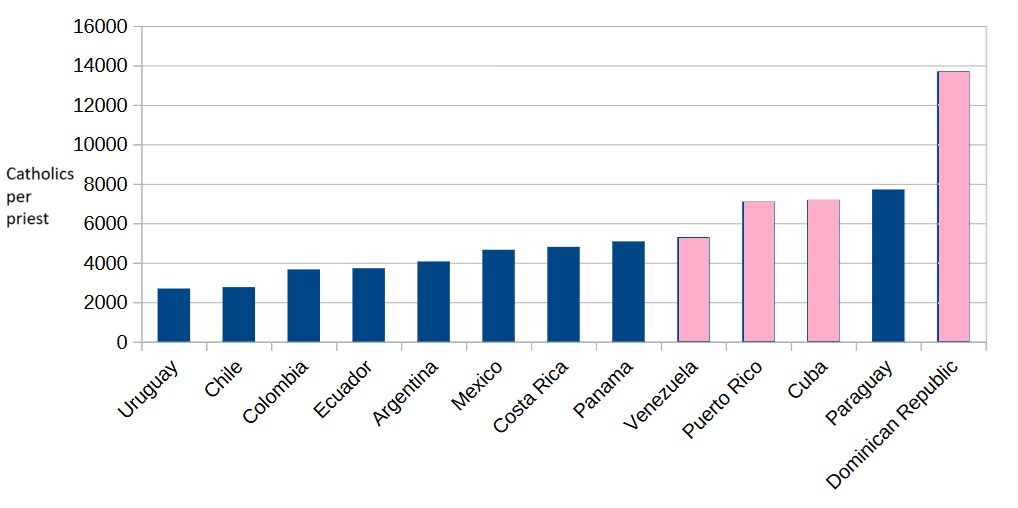

This contrast is also apparent in a bar chart.

The previous chart, contrasting the four Hispanic Caribbean countries that form the core of Canari America with other similarly Hispanic countries, makes the lower religiosity of this region of Latin America conspicuously evident.

(No, I have no explanation for why Paraguay has such a high ratio of Catholics per priest. I’m sorry. I’m not proposing that the religiosity, or the CPP ratio, of a population can be solely explained by the religiosity of its ancestral origins.

UPDATE: See footnote 7 of this later post)

Old frontiers and current borders

Until now, I have been using modern countries13, now restricted to only those with comparable levels of Spanish ancestry, as the geographic units for my comparisons of religiosity.

This assumes that the set of countries to which I have restricted the comparison can be neatly divided into those with a high degree of Canarian ancestry and those with slight or no Canarian ancestry. The former showing lower levels of religiosity, and the latter higher levels of religiosity.

Yet, the demographic and geographic reality is not so straightforward.

The migration of Canarians to the Caribbean was driven by push factors such as poverty, famine and natural disasters that compelled them to leave their home islands in search of a new life across the ocean.

It was also motivated by pull factors like the abundance of land in the Americas, a familiar tropical climate and agricultural practices, and Spanish colonial policies aimed at populating the sparsely settled Caribbean to face threats from rival European powers.

These factors led to disparate settlement patterns in what is now the Caribbean country of Venezuela, where certain regions became densely settled by Canarians, while others did not. Particularly, Venezuela’s Caribbean coast was an attractive target for Canarian colonization, whereas its mountainous Andean Region was much less appealing14.

A similar pattern of colonization can be observed in the neighboring country of Colombia, as I mentioned in a previous post:

In the 17th-century, Canarians started settling the Caribbean coast of northern Colombia in significant numbers, encouraged by the Spanish government which feared that the sparsely populated region would be a tempting target for foreign actors, including pirates.

These immigrants eventually imbued the Colombian Caribbean coast with a distinct Canarian character, similar to that found in other Caribbean regions. Even now, the local Spanish dialect, Costeño, more closely resembles other varieties of Caribbean Spanish than it does the Spanish spoken in the Andean interior of Colombia (Paisa, Cundiboyacense, etc).

If the variations in religiosity among different regions of Latin America are primarily attributable to varying degrees of Canarian colonization, shouldn’t we expect to see a similar phenomenon across different regions of Colombia and Venezuela?

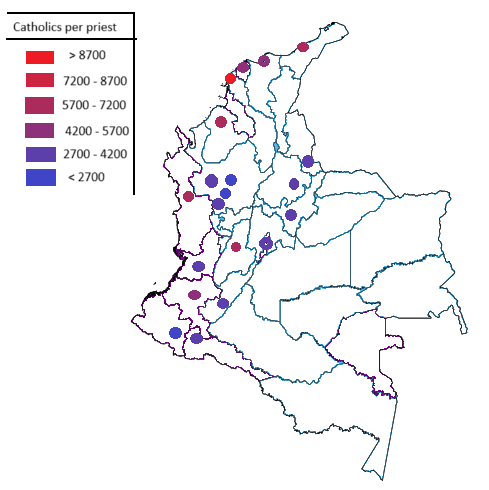

Bellow is a map showing the Catholics per priest ratio for each Colombian diocese in 1950:

The pattern is maybe not as clear as that seen across the whole of Latin America, yet a noticeable trend emerges with higher (red) CPP ratios along Colombia’s Caribbean coast (up North), the region where Canarian settlement was more intense.

In fact, the CPP ratio for Colombia’s Caribbean coast15 stands at 6,705 Catholics per priest, well within the range of Canari America. And conversely, when excluding its Caribbean coast, Colombia’s CPP ratio goes down to less than 3,100.

A similar exercise for Venezuela results in a CPP ratio of 5,508 when excluding its Andean Region, and a CPP of 4,547 for Venezuela’s Andean Region (dioceses of Mérida and San Cristóbal)16.

So, dividing Colombia into a Caribbean and a non-Caribbean region seems to corroborate the relationship between Canarian influence and lower religiosity. While applying the same division to Venezuela, although it doesn’t contradict the premise, does not provide such a strong support for the relationship17.

I’m being uncharitable, or something

Throughout this post, I’ve assumed that a higher ratio of Catholics per priest indicates lower religiosity. When a Catholic diocese has fewer priests in proportion to its Catholic population, it suggests that its flock “consumes” less spiritual services, and consuming less of an essentially free18 service reveals a lower (relative) preference for that service.

This is a demand-focused interpretation of the Catholics per priest ratio.

And it seems to me that this interpretation aligns well with the colloquial understanding of “low religiosity”. Not many parishioners in churches, and not many priests in churches either.

Then, there is the supply-focused interpretation of the Catholics per priest ratio.

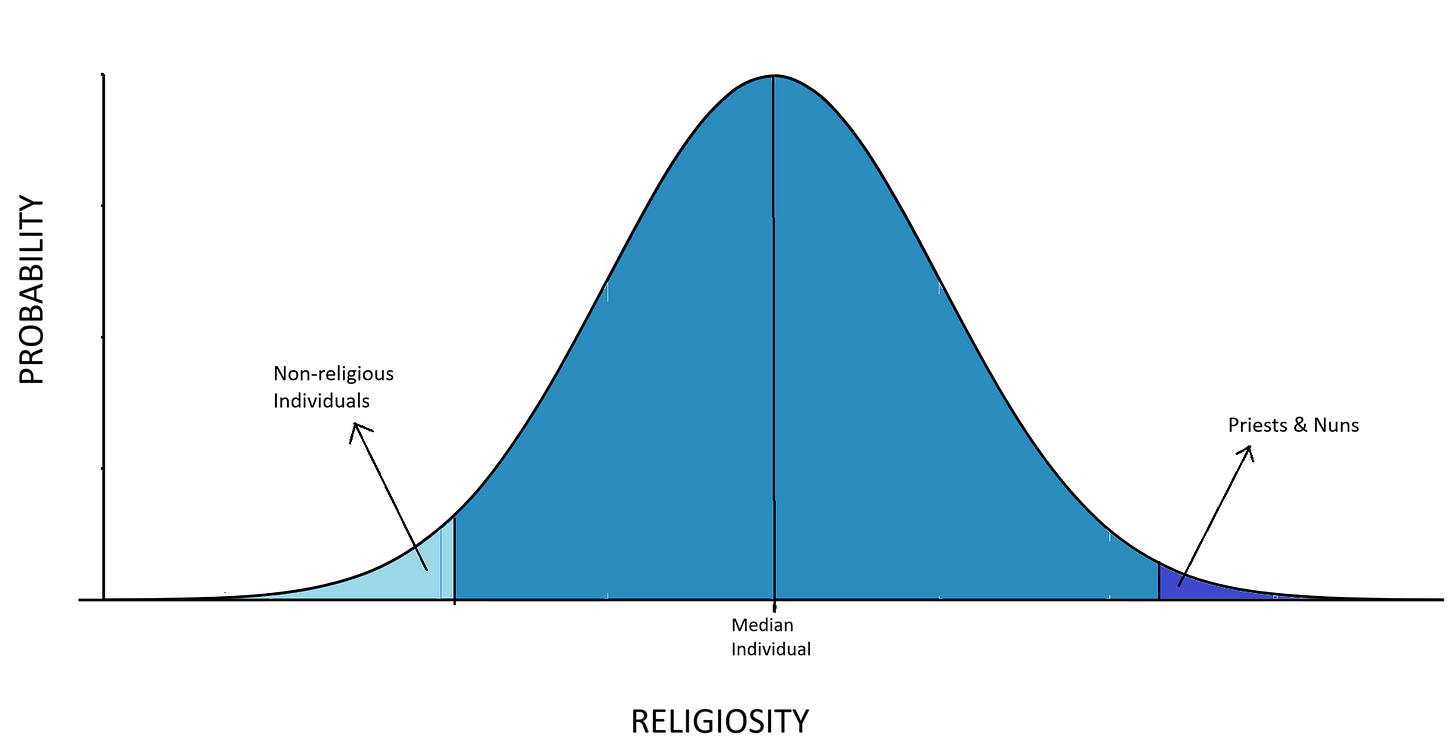

Each individual has a certain degree of inclination towards matters of the spirit. A small minority may exhibit little to no interest in these matters, but conversely, at the opposite end of the religious inclination spectrum, another small group will have a high preference for religious pursuits, actively engaging in the religious life of their community, above and beyond what is minimally prescribed by their religion.

A few in the latter group have such a high preference for religious life that they will dedicate themselves entirely to this calling19. Within a Catholic community, these select few might choose to become priests or nuns.

Assuming that the religious inclination of individuals conforms to a normal distribution, we can graphically represent the religious inclination distribution in the following way:

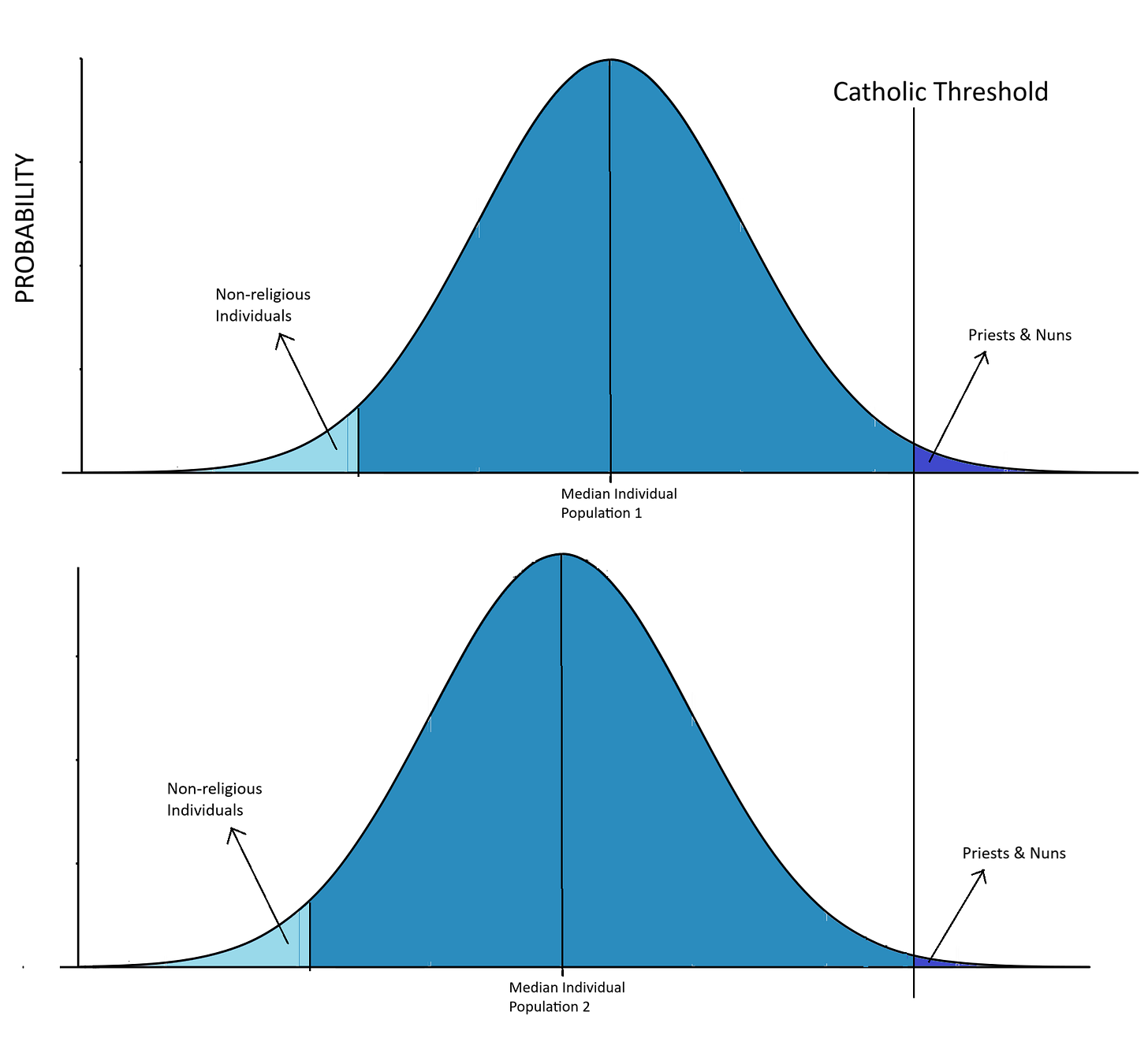

If there is a threshold in the religious inclination distribution beyond which individuals will choose to pursue a religious life (as I imply in the previous chart), this threshold can largely be attributed to the characteristics of the religion that the population adheres to, rather to the inherent traits of the population itself.

Regardless of an individual’s perceived level of religiosity (relative to others?), the Catholic Church sets specific requirements - a threshold - that must be met by those seeking to take lifelong vows.

For two distinct (Catholic) populations with two differing distributions of religious inclination, this threshold will be positioned at different points along their respective distributions.

The variations in religious inclination between different populations imply that, all else being equal, these populations will supply significantly different numbers of priests. In particular, populations with a religiosity distribution shifted to the left - less religious - will produce less priests.

Not many priests in churches, and (likely?) not many parishioners in churches either.

Another feature of Canari America

Regardless of whether you agree with my view that the CPP ratio is a reliable indicator of religiosity, the fact stands that it captures a core feature distinguishing the various Catholic cultures within Latin America. A feature that is consistent over time, and correlates very strongly with Canarian influence and culture.

This is just one of several cultural traits that set Hispanic Caribbean countries, heavily settled by Canarians, apart from the rest of Latin America. And it plays an important role in explaining the unique identity and history of the Spanish Caribbean.

Defined in catholic-hierarchy.org’s main source, the Annuario Pontificio.

See “The Catholic Church in Cuba, 1959-62”, Joseph Holbrook.

The oldest CPP data available on catholic-hierarchy.org is precisely for 1950 - or 1948-1949 depending on the diocese. This data comes from the Annuario Pontificio of 1951. The earliest CPP data accessible on Catholic-Hierarchy.org dates back to 1950, or 1948-1949 for some dioceses, sourced from the 1951 Annuario Pontificio.

They still do, as of 2020.

Uruguay, Chile and Argentina had CPP values of 2,696, 2,764 and 4,067 respectively.

During the majority of the Spanish Civil War, Catalonia and most of Aragon were under Republican control.

In 1970, the two dioceses in the Canary Islands ranked as the second and fourth less religious in Spain based on their CPP ratio.

And migration from continental Spain was consequently larger.

The African component is of course also significant, but besides a few regions in some Latin American nations where African ancestry is dominant and African culture is a major source of the local identity, its weight is decidedly less than that of the other two components.

In Guatemala, approximately 60% of the population identifies as Ladino (mestizo), with the remaining 40% identifying as Maya or indigenous according to Söchtig et al. (“Genomic insights on the ethno-history of the Maya and the ‘Ladinos’ from Guatemala“, 2015). The Ladino population is approximately 40% European in ancestry while the Maya population is less than 10% European in ancestry (Figure 2C in Söchtig et al.).

Bolivia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Peru.

Or self-governing unincorporated American territory in the case of Puerto Rico.

Internal migration, particularly throughout the 20th century, has altered this settlement pattern, which is no longer as pronounced as it used to be.

The dioceses of Barranquilla, Cartagena, Guajira, Santa Marta and San Jorge (Córdoba).

The relatively small disparity between the CPP ratios of Venezuela’s two regions appears to be, at least in part, a consequence of the high concentration of priests in Venezuela’s capital of Caracas. If I exclude Caracas, the CPP ratio of Caribbean Venezuela raises to 7,363 (I’ll leave my speculations on this for another time).

I’d rather stick to comparing similar countries over reasonably proximate time periods and under similar social circumstances. But. I decided to calculate the ratios for Venezuela in the year 2000 anyways. In 2000, Andean Venezuela has a CPP of 7,202 (alternatively with Barinas 7,874; with Trujillo 7,510), while the rest of Venezuela has a CPP of 12,917. That is to say the Andean Region’s ratio is 45% lower than that of “Caribbean Venezuela”.

It’s not really free from the point of view of the congregation/parish. For the most part, it is the Catholic community itself that supports the priests who minister to them.

I think of this preference as a relative one. Relative to the array of activities that individuals can choose from. As the range of available activities expands over time, the threshold beyond which individuals choose a religious life over other options should logically shift further to the right in the distribution.

Hi, Javiero. Interesting analysis.

I'm not sure about the supply-side argument for more people called to be priests = more religious people, just because priests don't always (or typically) come from the local community. There were probably more home-grown priests in the past (i.e., in the 1950s), but certainly there were lots of transplant priests then, too. I mean, the whole premise of the Jesuits is that they should be sent hither and yon to found churches and schools.

For instance, I live on the Caribbean island of Saba, and our priest is from Poland. The priest before him was from the Philippines. Oh, by the way, Saba currently has a population of 2035, of which 50% are Catholic. So we've got one priest per about 1018 Catholics.

Living on Saba as I do, I wanted to see what Catholic-Hierarchy.org had to say about priests in the Dutch Caribbean. Alas, this is not possible, since this website clusters a ton of very disparate islands, from the Bahamas to the Virgins, as "antilles," of which the Dutch Caribbean (n.b., "Netherlands Antilles" is a defunct category, having been dissolved in 2010) is one part. So I did my own investigating.

The most recent photo showing all the priests in the Diocese of Willemstad, the diocese that includes all the Dutch islands of Aruba, Bonaire, Curacao, Saba, St. Eustatius, and St. Maarten is from 2016, and shows 38 priests (see here: https://diocesewillemstad.com/priest/ )

In 2016, there were on each island (see here for data on BES islands: https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/publication/2016/44/trends-in-the-caribbean-netherlands-2016):

Aruba: 105,000 people, 75% Catholic = 78750 Catholics

Bonaire: 19400 people, 68% Catholic = 13192 Catholics

Curacao: 160,000 people, 73% Catholic = 116,800 Catholics

Saba: 1900 people, 42% Catholic (yes, the population of Catholics on Saba has increased in recent years) = 798 Catholics

St. Eustatius: 3200 people, 24% Catholic = 768 Catholics

St. Maarten: 39,000 people, 33% Catholics = 12,870 Catholics

In 2016, therefore, we have a total of 223,178 Catholics and 38 priests, for a parishioner-to-priest ratio of 5873:1--not the lowest ratio, but not the highest. If there were a pixel for the tiny island of Saba on your map, it would be the darkest of dark blue, though.

I think this is interesting, because, per your Canaries hypothesis, the Dutch Caribbean's colonizing country, the Netherlands, is one of the least religious countries ever--both now, and at the time of conquest. And insofar as the Netherlands is religious, the official religion is Dutch protestant. In 2017, 51% of the Dutch were not religious. About 15% of the total population is some variety of Dutch protestant, and 24% is Catholic. (Data here: https://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/news/2018/43/over-half-of-the-dutch-population-are-not-religious) So, for the Caribbean Netherlands, it's not like the colonizing country is a Catholic powerhouse.

Your CCP ratio interpretation is radically WRONG. Northern Spain and very especially the Basque Country and Catalonia are extremely atheist/agnostic areas, probably even more than France. I'm Basque an most people is totally non-religious or even strongly anti-religious over here (and I know for a fact that only Catalans are in the same anti-religion page as we are in all the State of Spain). Andalusians on the contrary are famous for being hyper-religious and going totally nuts about Easter processions, for example.

The CCP ratio may have various interpretations but the most obvious one is that every parish gets one priest (maybe more but at least one) no matter how many Christians there are left, so higher CCP ratio surely tends to represent greater religiosity, not less.