Correction. And more data on litigiousness and trust

Incorporating Italy into my analysis of cooperation, litigiousness, and trust.

In my previous post I wrote:

I should probably look at French data from other years later on (see footnote 16) to better understand the variations in litigiousness in France,

And I was right. After checking data from previous years, I realized that the 2024 figures for French legal cases are still being revised. That means the litigiousness rates I reported for some French regions could rise and, of course, some could increase more than others1.

So, I did the calculations again. This time I calculated average litigiousness rates using French data from the years 2018, 2019, 2022, and 2023 to avoid having to revise the computed rates again in the future2.

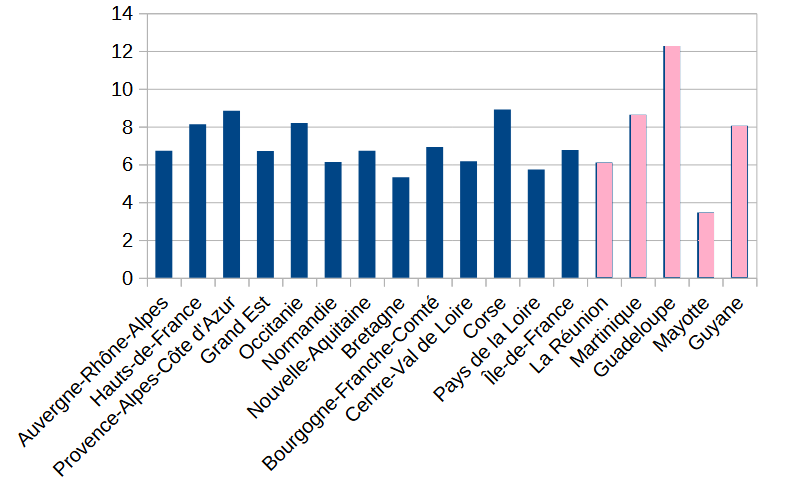

Here is the updated bar chart showing litigiousness per capita for each French region or overseas department.

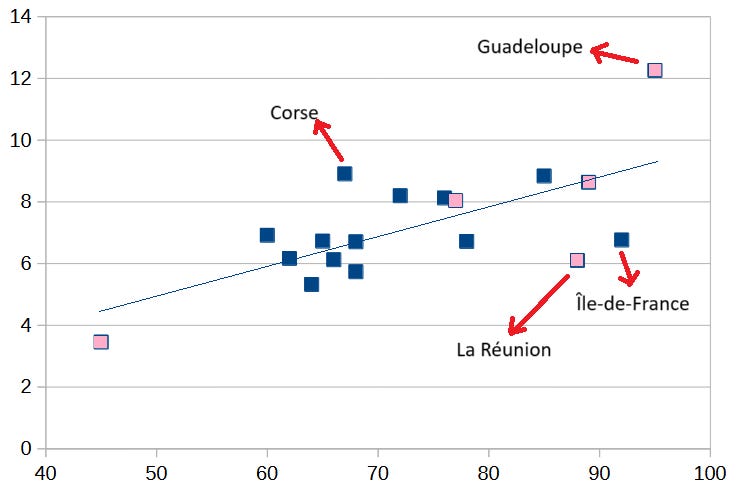

And here is the updated plot of litigiousness against urbanization rate.

This alters some conclusions about French litigiousness from my previous post, while others remain unchanged.

What results are affected?

Guadeloupe, not French Guiana, shows the highest litigiousness rate among all regions. So one French overseas department replaces another at the top spot.

Île-de-France, the region of Paris, is no longer the second most litigious French European region; it’s now an outlier (red arrow in the graph above) due to its low litigiousness.

And which conclusions remain unchanged?

Litigiousness remains strongly correlated with urbanization, although less so than I previously thought. The correlation coefficient drops from the 0.84 I previously reported to 0.67.

Overseas departments and regions are still exceptional in terms of their litigiousness, with two out of five territories as outliers: Guadeloupe with an exceptionally high rate of litigiousness and La Réunion with a remarkably low rate.

It’s also interesting to note that Corsica, the culturally Italian island which only became part of France in 17693, stands out in the updated plot as a highly litigious outlier.

Now that I’ve used better French data, certain data points have shifted in the litigiousness vs urbanization plot, but the general result - that regions with distinct cultures also diverge in litigiousness - still holds.

And it also holds in Spain, where the Canary Islands and the Basque country4 diverge from mainstream Spanish culture.

Also in my last post, I briefly touched upon the subject of social capital. Now, I would like to explore it a bit further, starting with the work of Robert Putnam, one of the most influential academics writing on the subject of social capital5.

Putnam’s first work in the area of social capital was Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. published in 1993. It is a comparative study of regional governments in Italy that drew great scholarly attention for its argument that the success of democracies depends in large part on the horizontal bonds that make up social capital. Putnam writes that northern Italy’s history of community, guilds, clubs, and choral societies led to greater civic involvement and greater economic prosperity. Meanwhile, the agrarian society of Southern Italy is less prosperous economically and democratically because of less social capital6.

Putnam is widely recognized for his research on Italy and the U.S., and while his definition of social capital as “connections among individuals - social networks and the norms of reciprocity and trustworthiness that arise from them” is well regarded, other scholars, such as Pierre Bourdieu7, propose a slightly different definition.

social capital is the sum of the resources, actual or virtual, that accrue to an individual or a group by virtue of possessing a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition8.

These scholars emphasize horizontal bonds, or network ties, as a key (potentially measurable?) social structure underpinning social capital.

Yet, at least in the case of Putnam, trust is also explicitly mentioned as a foundation of social capital, though in the following quote, civic life - a more measurable aspect of it9 - substitutes for social capital:

Certain communities do not enjoy a more vital civic life because they are prosperous, they are prosperous because they have a vital civic life. How do you make democracy work better? Start by strengthening the norms of trust, reciprocity and civic engagement that are indispensable to collective existence10.

Notice how Putnam relates civic life (social capital) to prosperity and democracy. This proposed link is likely a major reason behind the growing interest in social capital over the last few decades.

Despite these links, there is some controversy regarding whether, beyond the clear social benefits of having more social capital, there might also be some adverse effects stemming from certain forms of social capital, such as criminal networks.

In that debate, I’m inclined to answer no, based on social capital’s trust element. Criminal networks don’t operate on trust, but on a “don’t betray us or we’ll kill you“ rule. Criminal networks do not constitute social capital.

Now that I’ve hopefully made the fuzzy concept of social capital a little less vague, I’ll follow Putnam’s lead and take a look at Italy, the focus of much of his academic work.

La bella fiducia11

Before presenting any data on Italy, I must concede that the data I’m about to show you would likely not be acceptable to some scholars studying social capital.

Why? Because most sociologists measure social capital by focusing solely on one indicator, membership in voluntary associations, over all others.

When it comes to tackle people’s community involvement, all comparative studies of social capital focus on membership in voluntary associations… Admittedly, supposedly civic attitudes, such as interpersonal trust and trustworthiness, are used as indicators of social capital as well…. But civic attitudes are not accepted as indicators of social capital among scholars who follow Coleman (1990) in insisting that social capital should be defined as referring only to community networks and not psychological attribute12.

Luckily, I’m not a sociologist, and I don’t feel obligated to use only voluntary association membership figures to assess Italian social capital. So I won’t.

I must confess though, that I’m not the first to measure Italian social capital using other indicators. In their 2004 paper, “The Role of Social Capital in Financial Development”, Luigi Guiso, Paola Sapienza and Luigi Zingales employed three alternative indicators to measure social capital: voter turnover in referenda, anonymous blood donations and incidence of cooperatives before 1915.

I do plan to take a look at cooperatives’ figures and voter turnover in the future, but for now, I’ll just focus on Italian litigiousness.

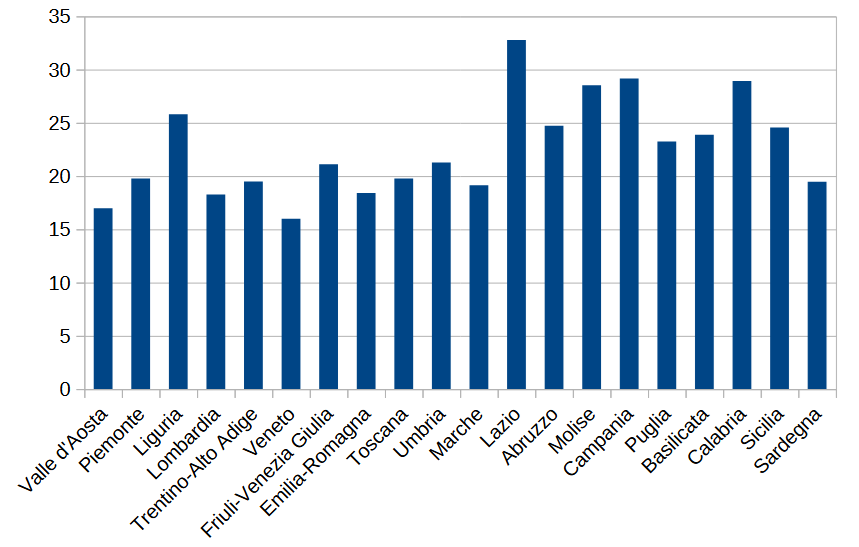

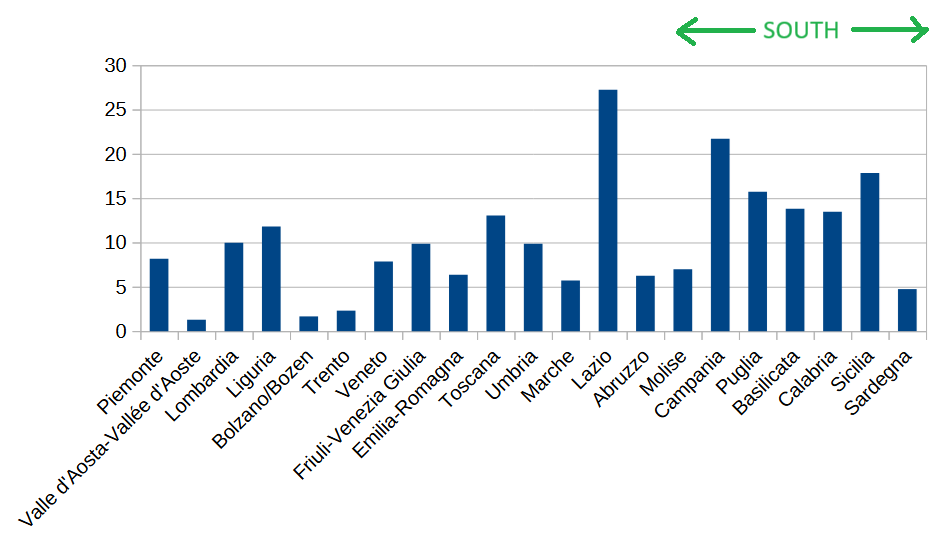

So, without further ado, here’s a bar chart of litigiousness13 per capita for each of the twenty Italian regions.

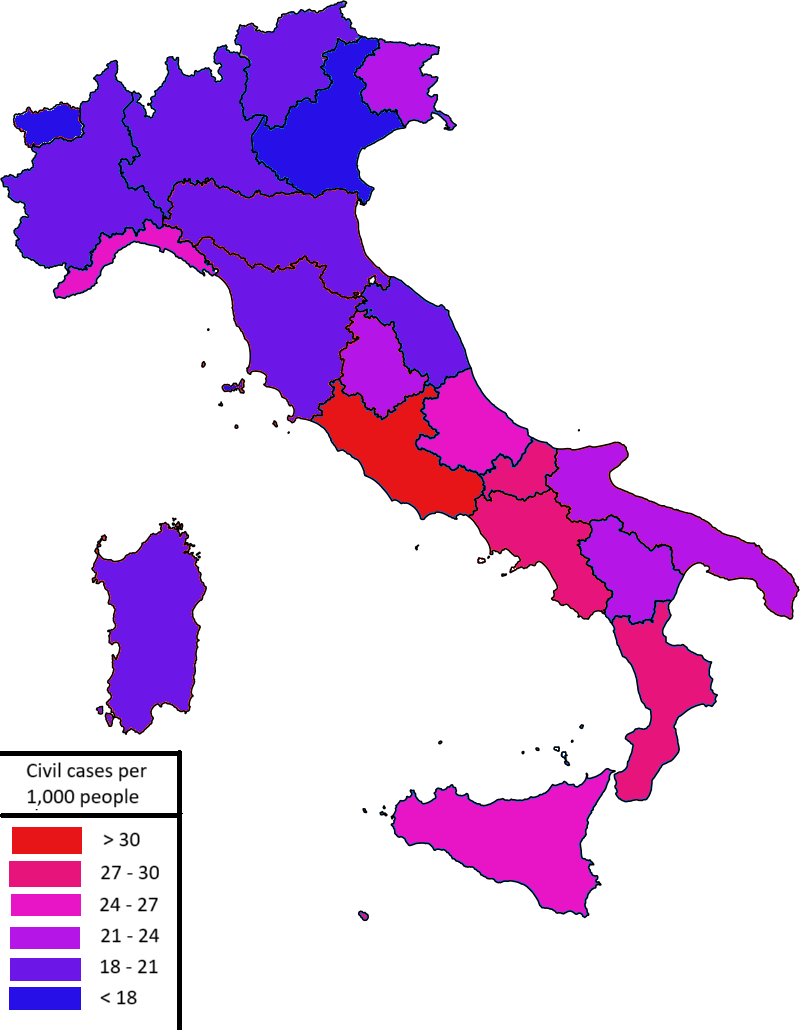

Or better yet, a map of Italy showing the same data:

The contrast in litigiousness between northern and southern Italy is remarkable. With the exceptions of Liguria and perhaps Friuli-Venezia Giulia, the north is substantially less litigious than the south.

This is the same divergence that Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales (GSZ), and many others before them, have noticed:

In 1958 when Banfield wrote “The Moral Basis of a Backward Society”, few economists, with the exception of Arrow noticed. His thesis that the underdevelopment of Southern Italy was due to the lack of social trust outside the strict family circle was hard to reconcile with the economic models prevailing at that time. Forty years later, however, developments in economic theory allow us to appreciate the intrinsic limitations agents face in contracting and the potential role social capital can play in reducing the deadweight loss generated by these limitations14.

And among southern regions, Lazio - home to the capital, Rome - is the most litigious, with a rate 45.5% higher than the Italian national rate15. This mirrors the case of Madrid, Spain’s capital and second most litigious region, with a rate 29.5% above the Spanish national rate.

There are reasons to doubt that Lazio has the most litigious culture in Italy, even if Lazio is nevertheless a highly litigious region16. First reason is: Lazio’s rate, like that of Madrid, might be inflated because it hosts the country’s capital. Second reason is: IANAL (I am not a lawyer). I might not have chosen the best legal categories to reflect litigiousness tied to trust - though I did my best effort.

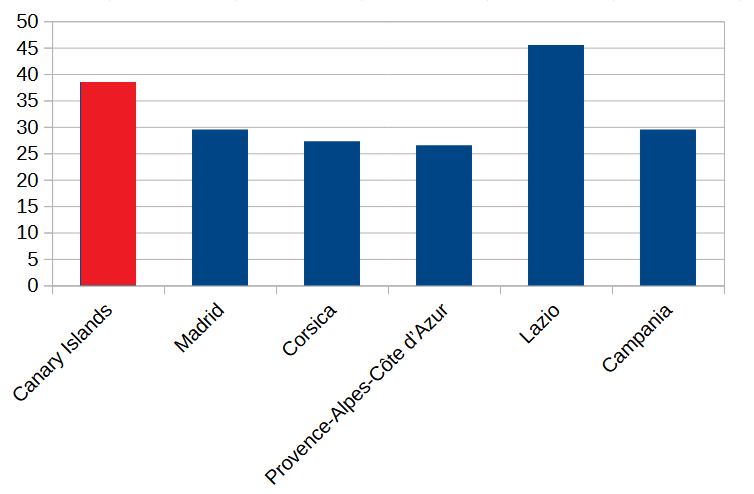

To better compare these French, Italian, and Spanish regions I’ve been talking about, here’s a chart showing how much more litigious the two most litigious regions in each country are compared to the rate of their nation.

At first sight, the Canary Islands don’t look as divergent from the rest of Spain as Lazio does from the rest of Italy, but the archipelago would probably look more divergent if I could adjust Lazio’s rate to remove the effect of hosting the national capital (see footnote 15).

Once more, I must stress that comparing levels of litigiousness across countries with different legal systems is a perilous task. My view is not that the Canary Islands are definitively the most litigious region across the three countries analyzed, but that they diverge from its national (Spanish) level more than any other region - with the already noted exception of Lazio.

Italians’ culture runs deep in their veins

Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales (GSZ) propose that blood donation, one of their three social capital measures, relies on purely “altruistic” behavior as it is not compensated in Italy17.

I agree with them, and indeed, I believe trust and cooperation are interconnected. The more you trust your fellow citizens, the more likely you are to cooperate with them, and act altruistically toward them. Correspondingly, greater cooperation foments trust in others.

In fact, blood donations in Italy have a strong inverse correlation with the litigiousness levels I just calculated, with a coefficient of -0.6618. Generally speaking, the more blood donations take place in an Italian region, the less litigation occurs in that region.

I’m very interested in blood donations as a measure of cooperation - and perhaps altruism - not only for its reliability and (I assume) availability, but also because it lacks a limitation that other measures suffer from: donation data can be compared across many countries and territories without worrying about local legal frameworks (litigiousness, cooperatives), political systems (voter turnover), or local cultural factors19 (sports association membership) affecting the comparison.

But for now, I don’t have any more data on blood donations.

Until contention do us part

Since I’m already writing about trust and cooperation, I thought I might take a look at one of humankind’s most fundamental cooperative institutions: marriage. My reasoning is, if a society has low levels of trust and cooperation, I would expect that this cooperative partnership would dissolve more frequently among members of such a society.

I’ve already accounted for divorces within the Affari contenziosi category of legal cases, which I included when measuring the litigiousness rates of Italian regions; but I wanted to see, probably influenced by a news report about the Canary Islands having the highest divorce rate in Spain, whether divorce rates in Italy show any geographic pattern.

And the answer is: no.

There’s definitely no discernible pattern20.

And then, while I was wallowing in defeat, I noticed something in the figures for Italy’s various divorce processes.

Italy has four different divorce processes that differ in whether they involve lawyers or not, whether they involve the courts or not, and most importantly, whether the process is contentious or consensual:

Judicial at the courts; not consensual (Giudiziali presso i tribunali).

Consensual at the Courts (Consensuali presso i Tribunali).

Consensual with negotiations assisted by lawyers (Consensuali con negoziazioni assistite da avvocati (ex art.6)).

Consensual at the civil registry office; no courts (Consensuali presso lo stato civile (ex art.12)).

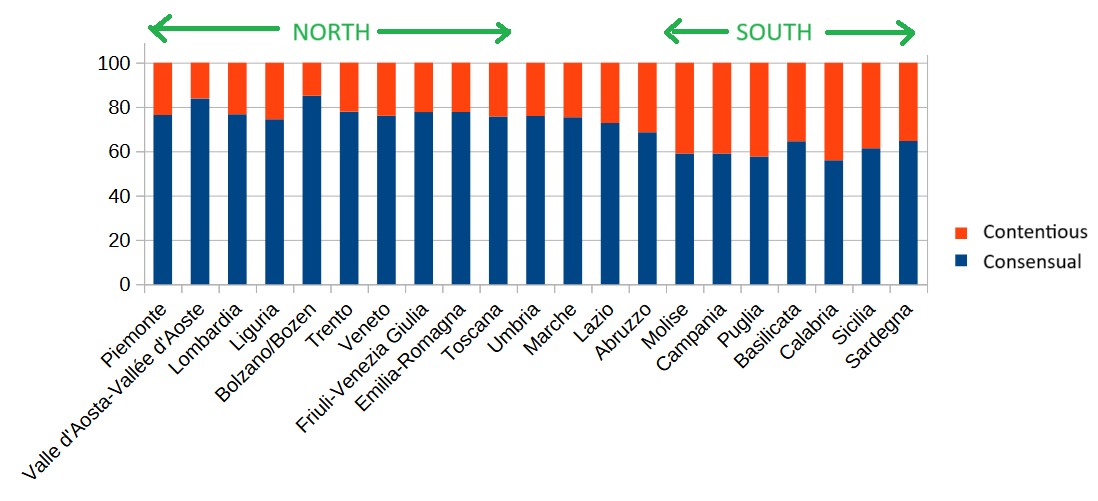

Using this data I can now differentiate between contentious divorces (“you heartless snake! you freeloading vulture!”) on the one hand, and consensual divorces on the other (we’ve shared years together, let’s just cooperate one last time).

And the results are remarkable: in some regions, less than 20% of divorces are contentious, while in others over 40% are.

Once again, southern Italy appears more contentious/litigious than the north.

The takeaway seems to be that divorce numbers, influenced by population structure (proportion of divorce-age individuals) and marriage rates, are a poor measurement of trust or cooperation, while the rate of contentious divorces appears to be a much better indicator.

The only reason I can think of that could explain the higher rate of contentious divorces in southern Italy, other than a more confrontational culture, is that the south’s relative poverty might encourage former spouses to prefer a contentious divorce in hopes of securing a better economic outcome.

Yet this seems unlikely to me, given that consensual divorces assisted by lawyers are more favored in southern Italy compared to the other two consensual divorce options; and, as you might expect if you’ve dealt with lawyers in the past, the consensual divorce with negotiations assisted by lawyers unsurprisingly turns out to be the most expensive type of consensual divorce.

Seems implausible that southern Italians prefer contentious divorces for economic reasons, but then also prefer divorces assisted by lawyers over other forms of consensual divorce.

So I’m sticking with the confrontational culture hypothesis.

I will probably apply what I’ve learned from writing this post to other countries in the near future, but for now, my main conclusion is that even in a country like Italy, known for large regional differences in social capital, there remains untapped data that could add to our understanding of social capital.

Also, fixed a minor error regarding Guadeloupe’s population. It’s 378k people, not 395k.

I excluded 2020 and 2021 to avoid the potential impact COVID may have had on those years.

The same year Napoleon was born in the island.

Alongside Navarre.

He’s the eighth most cited author on English-language political science syllabi according to the Open Syllabus Project.

Bourdieu is the seventh most cited sociology author, according to the aforementioned Open Syllabus Project.

Wikipedia article on Bourdieu. I disagree with him on the “accrue to an individual” part.

According to Wikipedia’s article on Putnam, civic, social, associational, and political life equate to, or closely approximate, social capital.

“What makes democracy work?“, Robert Putnam (1993).

Yes, fiducia is the Italian word for trust.

“Social Capital, Voluntary Associations and Collective Action: Which Aspects of Social Capital Have the Greatest ‘Civic’ Payoff?“, Welzel, Inglehart and Deutsch (2005). Grok disagrees about Coleman, though: “James Coleman, another key sociologist, defines social capital functionally - structures like obligations or information channels that facilitate action - where trust is just one component, not the whole. He doesn’t position trust as synonymous with social capital, suggesting they’re distinct but related: trust enables social capital but isn’t identical to it.”

The categories of legal cases included are: Contentious affairs, Labour, Social security and welfare, and Voluntary jurisdiction affairs (Affari contenziosi, Lavoro, Previdenza e assistenza, Affari di volontaria giurisdizione). I excluded mostly bankruptcy cases: Mobility foreclosures, Immovable property foreclosures, Bankruptcy applications, Bankruptcy, Other insolvency procedures, Declaration phase - judicial liquidation, Declaration phase - CCS procedures, Declaration phase - other insolvency procedures, Execution phase - judicial liquidation, Execution phase - CCS procedures, Execution phase - other insolvency procedures (Esecuzioni mobiliari, Esecuzioni immobiliari, Istanze di fallimento, Fallimenti, Altre procedure concorsuali, Fase dichiarativa - liquidazione giudiziale, Fase dichiarativa - procedure di CCS, Fase dichiarativa - altre procedure concorsuali, Fase esecutiva - liquidazione giudiziale, Fase esecutiva - procedure di CCS, Fase esecutiva - altre procedure concorsuali).

“The Role of Social Capital in Financial Development”, Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales (2004).

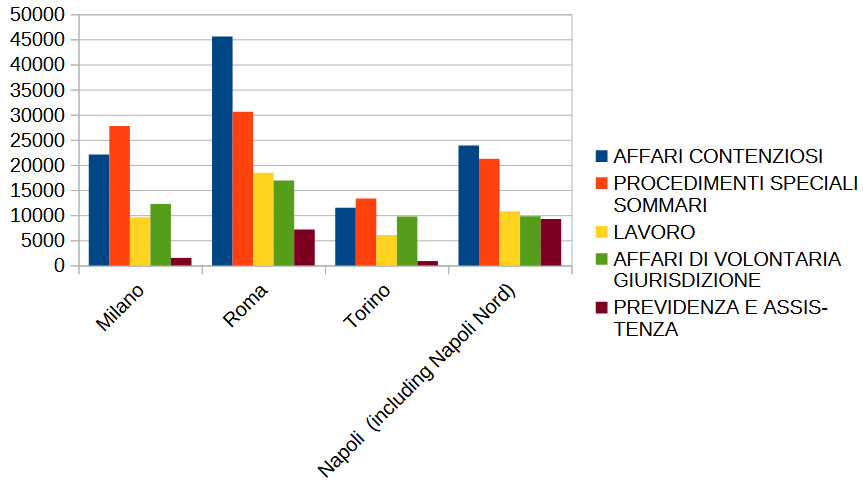

Comparing Rome to the other major Italian cities, it appears that the exceptional litigiousness of the capital is concentrated mostly on Contentious affairs (Affari Contenziosi). If I try to adjust for this effect (by using the number of cases that would be expected if Rome had the same rate as Naples in that category), the rate of litigiousness of Lazio remains very high at 29-30 cases per 1,000 people - though less than 34% above the national rate.

Excluding Rome, the provinces of Lazio have litigiousness rates ranging between 20 and 30 per 1,000, suggesting that, even if Rome’s rate were close to that of its surrounding provinces, Lazio would likely still be among the top five or six most litigious regions.

“The Role of Social Capital in Financial Development”, Guiso, Sapienza and Zingales (2004). This is true when talking about paid compensation, though blood donation is compensated with a paid day off work in Italy.

For the year 2023. Compiled by Grok using data from the Italian Blood Donors Association (AVIS).

Unless we are talking of an area with a with a significant Jehovah’s Witnesses population.

Don’t let news reports influence you.

Hey, really love your posts man, you go really in depth into some really unique and niche topics no one else seems to cover. Question for you, how do you source ideas (and find research) on what to write about?