The riddle of Canarian political elites in Latin America

Also, Basques and others in Cuba, Uruguay and Venezuela

In my previous posts exploring the impact and cultural contributions of the Canary Islands in Latin America, I’ve noted that the small country of Uruguay experienced considerable immigration from the Canary Islands.

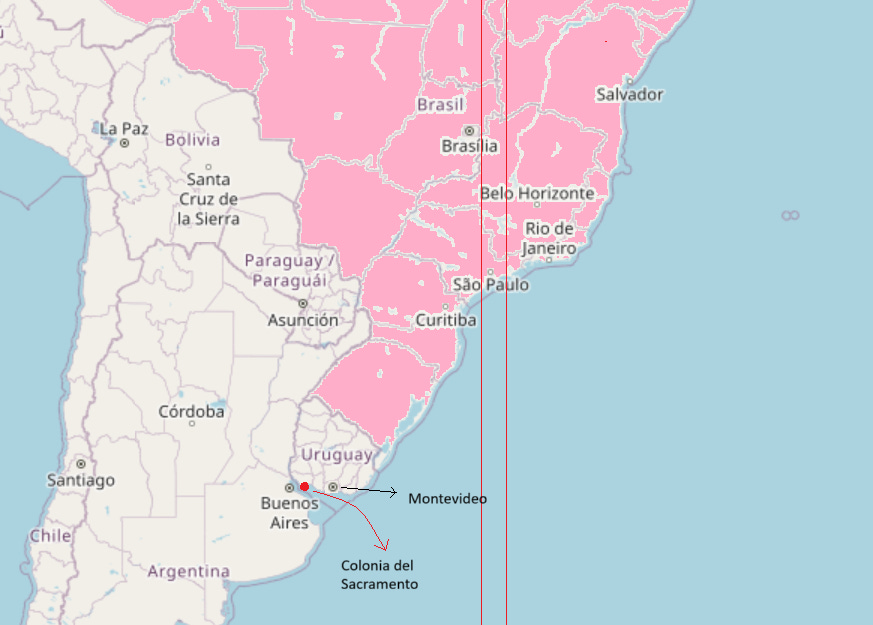

Despite being far from the Caribbean, where most Canarian settlement took place, Uruguay received a substantial number of Canarian settlers due to its location between the major Spanish colonies of the River Plate (current Argentina and Paraguay) and the neighboring Portuguese colony of Brazil.

Portuguese encroachment in the region, exemplified by the founding of Colonia del Sacramento in 1680 in contravention of the treaty of Tordesillas, prompted Spanish authorities to adopt similar colonization policies as those used in the Caribbean, by settling Canarian colonists in Uruguay - then known as the Banda Oriental, or Eastern Bank, of the River Plate.

After several decades, Spanish authorities established Montevideo as a port in the Banda Oriental to counter Portuguese influence and serve as a base for further colonization. The founding population of Montevideo, as well as many subsequent cities, largely came from the Canary Islands.

In the first expedition on the ship "Nuestra Señora del Encina", which left Santa Cruz de Tenerife on August 21, 1726, the families of Aquino Rivero García and Bernabé González were present, and in the second in 1729, which was on the ship "San Martín" that arrived in Montevideo on March 27, 1729, the Lanzarote families of Lorenzo Calleros Sosa, Antonio Méndez and Cristóbal Cayetano de Herrera were present. All of them contributed to the founding of the city of Montevideo1.

After multiple successful sieges of Colonia del Sacramento in 1680, 1705, and 1762, followed by several negotiated returns to Portuguese control, Spain permanently annexed the city in 1777. Despite the change of hands, some Portuguese settlers chose to remain, eventually becoming part of Uruguay’s population.

In 1828, Uruguay finally gained its independence as a sovereign nation after a long and tortuous process that spanned nearly two decades, which included a temporary annexation by Brazil (1817-1828). But the protracted wars and Brazilian occupation did not stop the influx of immigrants to Uruguay.

More than twenty expeditions of [Canarians from the island of Lanzarote] to Uruguay are recorded in the period from 1803 to 1845, the first one leaving from Santa Cruz de Tenerife and the last one led by the sons of Juan Bautista. We highlight the expeditions of 1838 in which the brig “Indio Oriental” left with 206 passengers, the brig “Zaragoza” with 515, the “Leonor”, “La Circunstancia” with 214 and the brig “Uruguay” with 1542.

Alongside these Canarian and Portuguese settlers, Galicians were among the largest groups of Spanish colonists in the Banda Oriental3. This migration during colonial times, together with the massive migration of Galicians during the late 19th century and early 20th century, explains the significant Galician ancestry in the modern population of Uruguay, and it’s reflected in the high prevalence of Galician surnames among Uruguayans.

Surnames

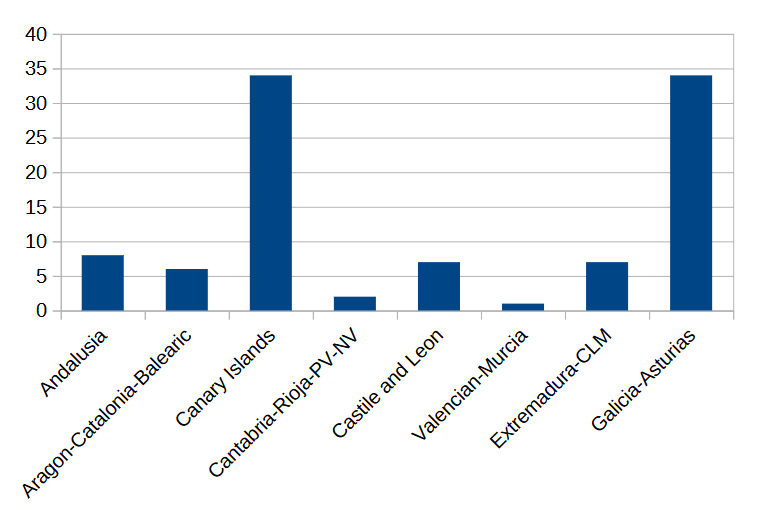

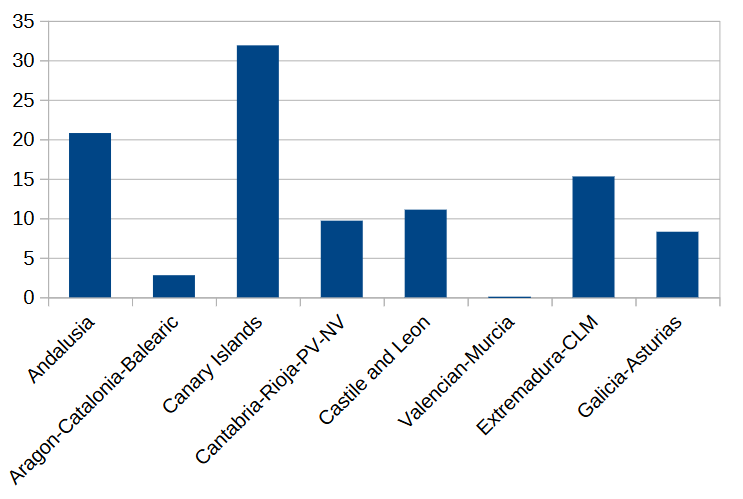

I did a surname analysis of the most common surnames in Uruguay, and according to its results4, Galician surnames represent around 32% of all5 surnames among the modern Uruguayan population while Canarian surnames represent around 34%6.

After doing an initial analysis where each Spanish autonomous community was considered separately, I then grouped7 some autonomous communities into regions for easier comparison between regions. This means that Galicia and Asturias are now combined into a single region, while the Canary Islands remains as a separate region.

I should remark that this surname analysis excludes European regions beyond Spain, such as Italy, a large source of 19th-century immigrants to Uruguay, and Portugal, which has also contributed to Uruguayan ancestry in more recent times through Brazil.

(For context, the only other South American country with a long8 and densely populated9 border with Brazil is Paraguay, where a little less than 10% of the population has Brazilian origins)

The results of the analysis should give a reasonably accurate depiction of the real contribution of each Spanish region to the ancestry of the modern Uruguayan population, and they confirm that the extensive history of Canarian and Galician migration to the country had a significant impact:

To visualize these results geographically, a map showing Uruguayan ancestry by Iberian10 region might look something like this:

And that looks heavily skewed towards the western side of the Iberian Peninsula11.

In fact, Canarian and Galician ancestry are so prominent in Uruguay that they overshadow the contributions from two regions traditionally seen as major sources of migrants to the New World: Andalusia and Extremadura.

For comparison, here is the distribution of surnames by Spanish region in Venezuela, another country which received substantial Canarian immigration:

You can see that the percentages for Andalusia and Extremadura now rise to a significant level compared to Uruguay, while the Canarian share remains high at over 30%.

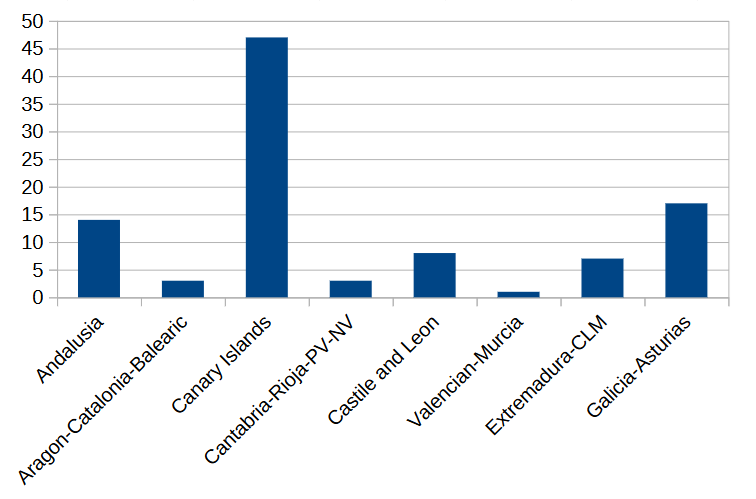

And now, let’s look at the distribution in Cuba, the country that likely received the highest levels of Canarian immigration in all of Latin America:

The results of the surname analysis suggest that nearly half of the Spanish ancestry within the Cuban population comes from the Canary Islands, which is very close to what I was expecting12. Yet it’s reassuring to confirm the reliability of these surname analyses because then I can apply this method to sets of individuals for which I have no other means to discern their approximate ancestry.

Elite ancestry

The set of individuals I have in mind is political elites. Elites, broadly speaking, wield disproportionate influence over the culture and society of the countries they lead, and this is also the case in Latin America. And among all elite groups, political elites stand out as the most influential.

I’m not just interested in how diverse migration patterns from various Spanish regions have impacted different Latin American countries, but also in how these patterns might account for the distinct compositions of Latin American political elites.

Of course, my interest rests on the assumption that the values and culture of different regions of Spain are sufficiently distinct to make the analysis of elite composition, rather than merely the ancestry of the general population, interesting in itself13.

And my goal here is twofold: to determine the general (approximate) ancestry composition of each country’s elites, and to track changes in that ancestry composition over time for each country.

Assuming each individual has the same chance of becoming part of the political elite, without considering background or prior knowledge, we would expect to find that the composition of the political elite mirrors that of the broader population14. For instance, in the case of Cuba, we might expect that Canarian surnames represent around half of the total for the country’s political elite.

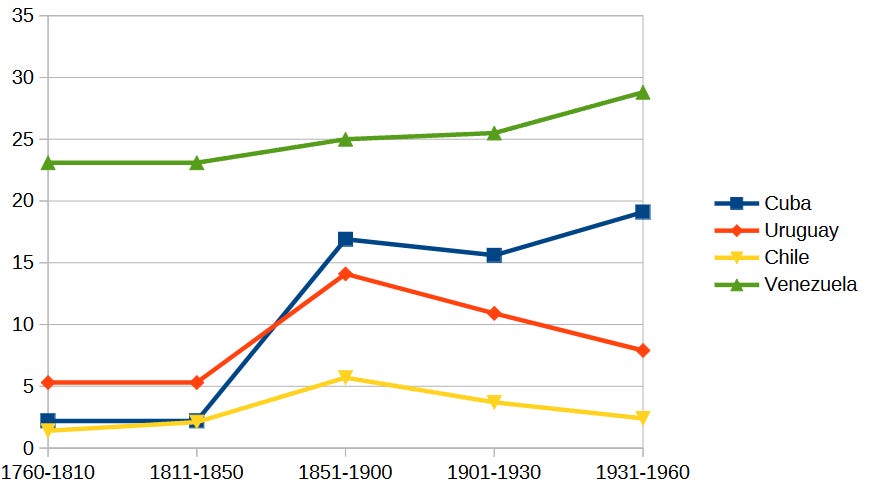

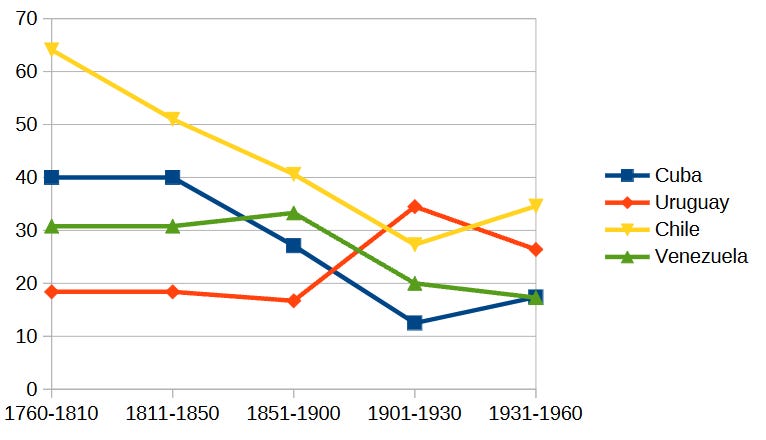

But, alas, that is not the case. The next chart shows the share of politicians15 with a Canarian surname for each of the three countries previously mentioned, broken down by year of birth.

A few observations about this chart:

I also included Chile for reasons that will become apparent shortly16.

Notice that the country with the highest share of Canarian politicians is not Cuba, but Venezuela.

Duplicated values for the time periods 1760-1810 and 1811-1850 in Cuba, Uruguay and Venezuela are due to an insufficient number of surnames in each period. I processed all surnames from the entire 1760-1850 period together17.

There is a noticeable increase in the share of politicians with Canarian surnames in Uruguay from 1811-1850 to 1851-1900, with an even more pronounced rise in Cuba.

Remember that the years in the chart are birth years. A politician born in 1875 might have a career spanning from 1900 to 1930, or from 1905 to 1940. The increase in Canarian politicians in Cuba and Uruguay became most evident in the 20th century.

However, the most striking observation from the chart is that the (implied) share of Canarian ancestry among the political elite is substantially lower than the Canarian ancestry share in the general population. This underrepresentation is small in Venezuela, but very large in Cuba and Uruguay.

In Uruguay, Canarian surnames are underrepresented among the political elite by a factor of approximately 3X, and in Cuba by a factor of roughly 2.5X.

That raises two questions:

Why are Canarian surnames underrepresented?

If the Canary Islands are underrepresented, what other Spanish regions are overrepresented?

Let’s start by tackling the second question. We already saw that Galician-Asturian ancestry is as prevalent in Uruguay as Canarian ancestry, and so it would be interesting to look at the proportion of Galician-Asturian surnames within Uruguay’s political elite.

Turns out that in Uruguay, the proportion of Galician-Asturian surnames among politicians is close to that among the general population, while in Venezuela, this proportion is slightly higher for politicians. There’s no major apparent disparity between the share of Galician ancestry among elites and the general population for these two countries.

In contrast, Cuba shows a more nuanced trend: during the 19th century, the share of Canarian surnames among politicians was similar to that of the general population, yet by the mid-20th century, there was a noticeable increase, resulting in an overrepresentation of Canarian surnames in the political elite.

I believe this remarkable upward trend might be connected to the first question I posed. But, returning briefly to the second question: if Galician-Asturian ancestry is not overrepresented in the political elites of Cuba and Uruguay, what ancestry is?

The Basques are Weird

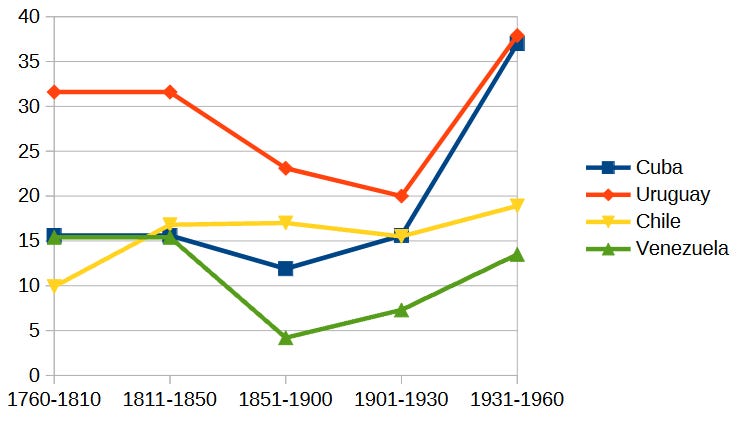

The answer, as anyone familiar with the Basque stereotype in Latin America might have guessed, is Basque ancestry. However, it’s not just Basque surnames that are overrepresented; rather surnames from the broader region of Central-Northern Spain: Cantabria, La Rioja, Navarre and, of course, the Basque Country.

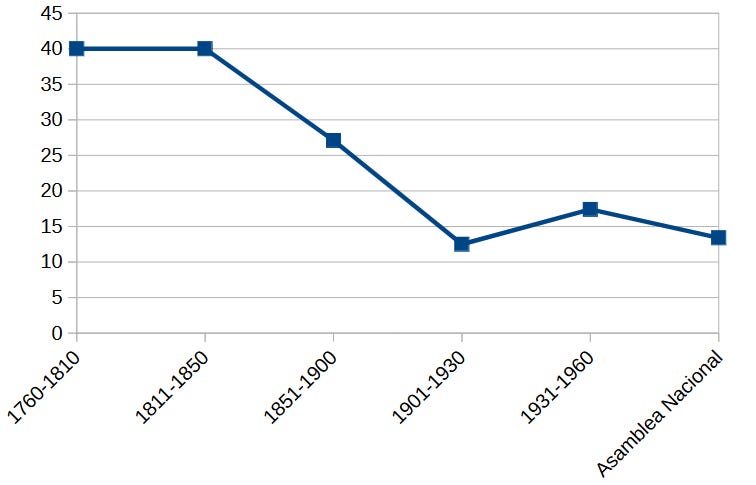

Here is the chart showing Cantabrian-Riojan-Navarran-Basque (or C-N for short) ancestry in our four countries:

And that’s the reason I wanted to include Chile in these comparisons. Chile likely has one of the highest shares of Central-Northern Spanish ancestry among its political elite, to the point where the overwhelming majority of Chilean politicians of the early 19th century had a surname hailing from the region.

The elite overrepresentation of C-N surnames is at least tenfold in Uruguay, varies between 10X and 5X in Cuba (depending on the time period; more on this later), and ranges from 2X to 3X in Venezuela (remember that conversely, Venezuela had the least underrepresentation of Canarian surnames).

Chile’s elite overrepresentation of C-N surnames falls within the 2X to 3X range, similar to Venezuela, but far from the overrepresentation seen in Cuba and Uruguay.

This is probably a good time to mention a caveat regarding these surname analyses. As time passes and descendants of Spaniards from different regions of the mother country intermarry in the New World, I would expect that the share of Canarian surnames (and other regions’ surnames) among the elite would increasingly reflect the proportion seen in the general population18.

This might be the reason why the proportion of C-N surnames in the Cuban political elite has been decreasing during the 20th century. You can see this trend in the previous Central-Northern surnames chart, but just to make sure, I’ve added an additional data point sourced from the members of the current Cuban National Assembly:

Beware that this is a different source for surnames of the political elite than the one I used previously19, which was Wikidata.

Nevertheless, this last chart does seem to indicate a trend of convergence between the elite share of (currently overrepresented) Spanish regions and the general population share in those regions (though the latest data point still shows a 4X overrepresentation of C-N surnames).

I used the plural “regions” because there is another region of Spain that is also clearly overrepresented20, and that is the region that groups Aragon, Catalonia and the Balearic Islands.

So, we have two Northern Spanish regions, which, based on the overpresentation of surnames originating in them, appear to have a disproportionate influence in the political elites of our four Latin American countries.

It seems to me that the answer to the pending question - why are Canarian surnames underrepresented in Latin American political elites - should be closely linked to why these other two Spanish regions are overrepresented.

Consequences

I’m not going to try to answer those two interconnected questions in this post. But I will speculate on the implications of this Canarian relative underrepresentation in elites.

Assuming that political elites adequately mirror the broader elites21, if there is any intrinsic reason why members of a specific group struggle to rise to the top when coexisting with other groups - even those as outwardly similar as other Spanish regional populations - then we might infer that this group struggles to nurture individuals with high levels of human capital, regardless of where it happens to reside.

This is just speculation on my part, but if true, it could have implications for areas of human development that rely on high human capital: economics, science, etc.

I’ll also add that Canarian elite underrepresentation is very unlikely to have resulted from systemic discrimination. During colonial times, Spaniards from the Canary Islands, for all practical purposes, were considered white and thus not subjected to any of the legal restrictions that non-white subjects of Spain faced.

In fact, in Venezuela, where Canarian underrepresentation is the least pronounced, Canary Islanders Canarians faced no barriers to social advancement:

Unlike what happened in Cuba, where [Canarians] importance within the ruling elite was much more reduced, in [Venezuela] a not inconsiderable part of its ruling classes was made up of individuals born in the Islands or their children.22

Whatever the cause of Canarian elite underrepresentation might be, it’s not due to discrimination.

In a future post, I plan to revisit this issue and try once again to answer the question of Canarian elite underrepresentation, or at least rule out another possible explanation.

“La Emigración de Lanzarote y sus causas”, Francisco Hernández Delgado y María Dolores Rodríguez Armas, 2010.

“La Emigración de Lanzarote y sus causas”, Francisco Hernández Delgado y María Dolores Rodríguez Armas, 2010.

These Galicians were initially recruited to settle Patagonia, but many ultimately ended up in Uruguay: “The Patagonian settlers were recruited from Spain, belonging to disadvantaged populations of Galicia and León.“

It goes without saying that you should take my estimates with a grain of salt. There is no 100% certain method to trace the (paternal) ancestry of thousands of 21st-century individuals who share a specific surname. All I can say is that there is a high probability that their original Spanish ancestor hailed from a particular region in Spain.

All surnames that can be more or less reliably considered as beloging to a certain region of Spain.

Compare that to the 30% I previously estimated, based on genetic studies of the Uruguayan population.

CLM is Castilla-La Mancha. Cantabria-Rioja-PV-NV is Cantabria-La Rioja-Basque Country-Navarre.

Relative to the sum of all the country’s borders. Not the case for Argentina.

Most of Brazil's borders with neighboring countries traverse the Amazonian forest.

I might eventually find a way to include Portugal as another Iberian region in the surname analysis.

Given the large contributions from Galicia, Portugal, and Western Andalusia to the colonization of the Canary Islands, I think it’s fair to categorize the archipelago as part of Western Iberia. Also, the regions of Castile and León, Extremadura-CLM and Andalusia all show a skew towards the western subregions of their territory.

My previous estimate, derived from genetic studies of the Cuban population, indicated a level of Canarian ancestry of approximately 45%.

To put it in “mathematical” terms, if the ancestry of country X’s population originates from regions A, B and C and its composition is 1:2:3, yet the ancestry composition X’s political elite is 3:2:1, that would be very noteworthy.

I must admit that before doing these analyses, I expected to find some disparity between the ancestry of the general population and elite ancestry, largely influenced by the widespread Latin American stereotype about Basque elites.

Politicians from each country were sourced from Wikidata (Q82955), defined by having the citizenship (P27) of that country. Surnames from the Canary Islands relative to the total from all Spanish regions. Both maternal and paternal surname if available. For Cuba, the selection criteria also included politicians born in Cuba between 1760 and 1900, many of whom held Spanish citizenship since Cuba did not gain independence until 1902.

The values for Chile are partly, though not entirely, noise.

The (not very reliable) results for each of those two periods were similar enough. I’m contemplating the idea of including businesspersons (economic-political elite) in order to have a larger set of surnames.

Also, for descendants of African slaves through the male line, the analyses provide no information about the regional origins of any Spanish ancestors they might have (if any).

I processed the names of 462 members (470 minus seven vacant and one missing) of the Cuban National Assembly. The average age of a member is 47 years, the median age is 46, and approximately two thirds of members were born in the 1970s and 1980s. Wikipedia lacks information on Cuban politicians born after the 1960s almost completely.

Besides Cantabria-La Rioja-Basque Country-Navarre and Aragon-Catalonia-Balearic the only other region that shows a consistent overrepresentation is Castile and León. But this is only a slight, no more than twofold, overreprepresentation relative to the general population and it seems to be restricted to Cuba.

I've experimented with expanding my definition of elite to include businesspeople and entrepreneurs, and so far, this broader definition hasn’t changed the results I’ve presented.

"Spanish and Islander". New data on the Canary Islands and independence of Venezuela. Manuel Hernández González (2018). Anuario de Estudios Atlánticos, nº 65: 065-014. http://anuariosatlanticos.casadecolon.com/index.php/aea/article/view/10260

Quite interesting, Javiero. I think you should have also considered non-Iberian surnames, which are prominent especially in the South Cone (what would be of Uruguay without Italians?, Chile without French and Germans?) but still quite good analysis.

It's interesting how Galicians have been rising in the political (and surely economic) elites. In contrast it seems to me that Basques and Catalans (but also Canarians and Valencians), unlike in Latin America, are very underrepresented in Spanish politics. I made a study years ago using only prime ministers (validos, presidents of the government) and non-monarchic head of states (presidentes of a republic and that pesky "caudillo"): https://forwhatwearetheywillbe.blogspot.com/2012/10/ethnically-speaking-who-rules-spain.html

Interestingly Galicians have also been increasing their political power in Spain but not at all Basques or Catalans, these last are the most discriminated against ethnicity in Spain, except for the First Republic, which lasted just months and tried to be federalist.