The Venezuelan election map: looking for structure in Venezuela's political culture

A tale of two Venezuelas.

In this post I want to discuss Venezuelan regional diversity and its relation to the results of the recent Venezuelan presidential election. But before I show you any Venezuelan election map, let’s take a moment to revisit my previous post on the demographic impact of Canarian migration to Latin America.

Based on that 40% estimate, there are approximately 7.7 million equivalent Canarian descendants in Venezuela, accounting for a quarter of the country's total population.

The combined total of equivalent Canarian descendants in those nine countries is 22.7 million people. This new world population of Canarian descent outnumbers the current native population of the Canary Islands by a factor of 14.

Canary Islanders have made an outsized demographic contribution to the formation of Latin America, with their contribution particularly concentrated in a few countries - or colonies prior to their independence from Spain. One such country is Venezuela, where by my own estimation a quarter of the average Venezuelan's ancestry can be traced back to the Canary Islands.

The Spanish empire actively promoted Canarian emigration to the New World as a strategy to protect its colonies from encroachment by foreign powers such as the English, Portuguese and French, settling the islanders in sparsely populated areas that were vulnerable to foreign attacks. The Caribbean coastal regions were the primary settlement areas, where the new settlers, accustomed to the semi-tropical climate of the Canary Islands, found it easier to adapt than mainland Spaniards.

Cuba is a great example of this. Canarians migrated to the tropical island in large numbers, ensuring it would avoid the fate of its neighbors Jamaica, which fell into English hands in 1655, and Western Hispaniola, which fell to the French in the 1660s.

Some notes on Venezuelan geography

The migration of Canarians to Venezuela did not exactly mirror that to Cuba, due to differences in their geographic characteristics. While Venezuela boasts a lengthy Caribbean coastline, it also features a temperate mountainous region in its southwest, which is an extension of the Andean region of Colombia.

While most Spanish settlers favored the temperate regions (circled in yellow in the previous map) over the tropical coastal areas (circled in red in the previous map), Canarians predominantly migrated to the Venezuelan coast and nearby valleys.

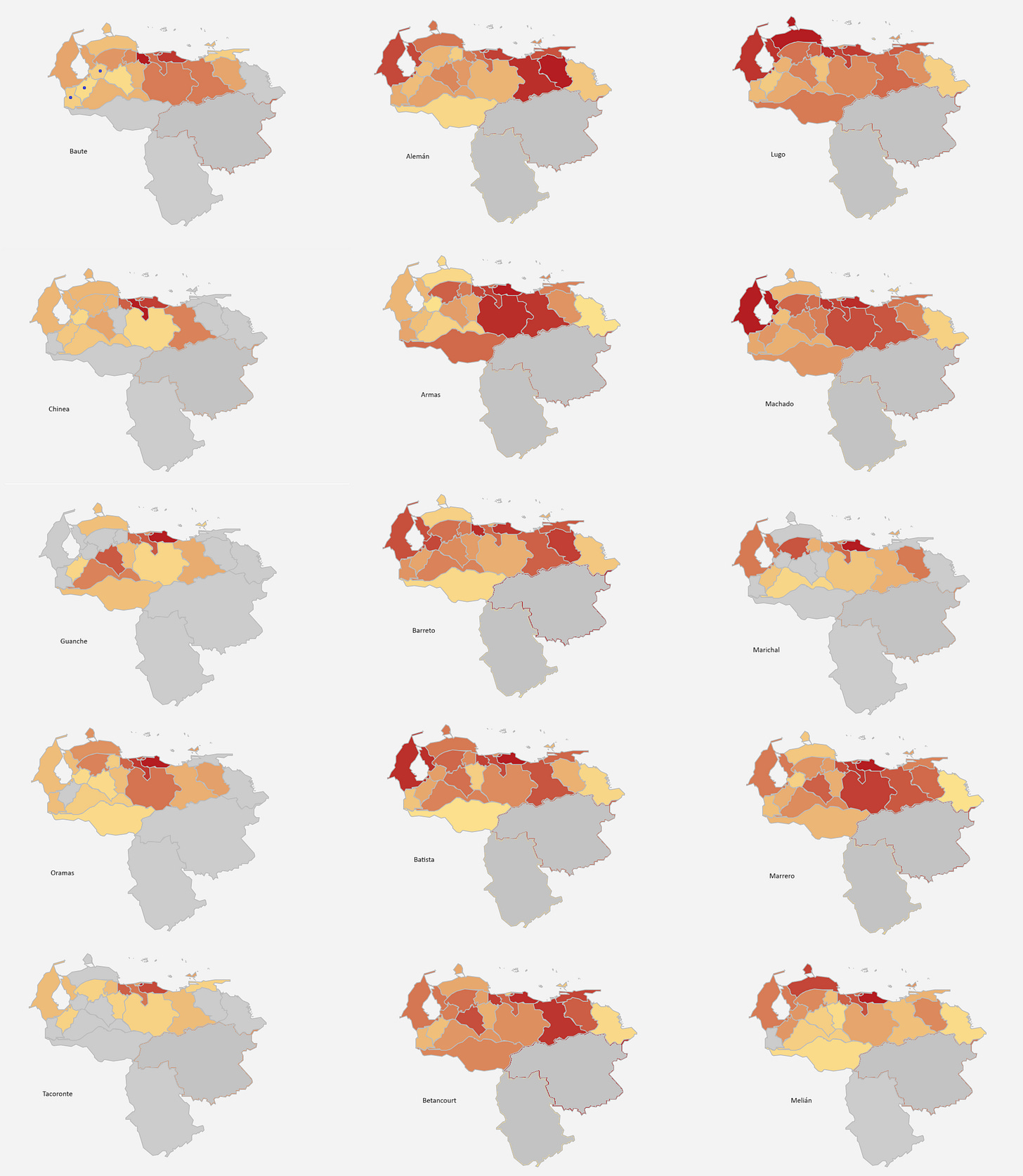

This pattern is evident even today when looking at a map of the geographical distribution of surnames across Venezuela.

The maps below display the geographical distribution of 15 Canarian surnames1, showing the expected high frequencies (many Venezuelans with those surnames) along the Caribbean coast of Venezuela2, and low frequencies in the three Venezuelan states that comprise the Andean region: Táchira, Mérida and Trujillo.

Compare the frequencies in the three Andean states (marked with a blue dot in the upper left map) with those in the Caribbean states. This reflects the little weight that Canary Islanders had in the creation of Venezuelan Andean society3, the society and region of Andinos, despite their enormous impact on the formation of Venezuelan society as a whole.

But what do these Canarians and Andinos have to do with the recent presidential election?

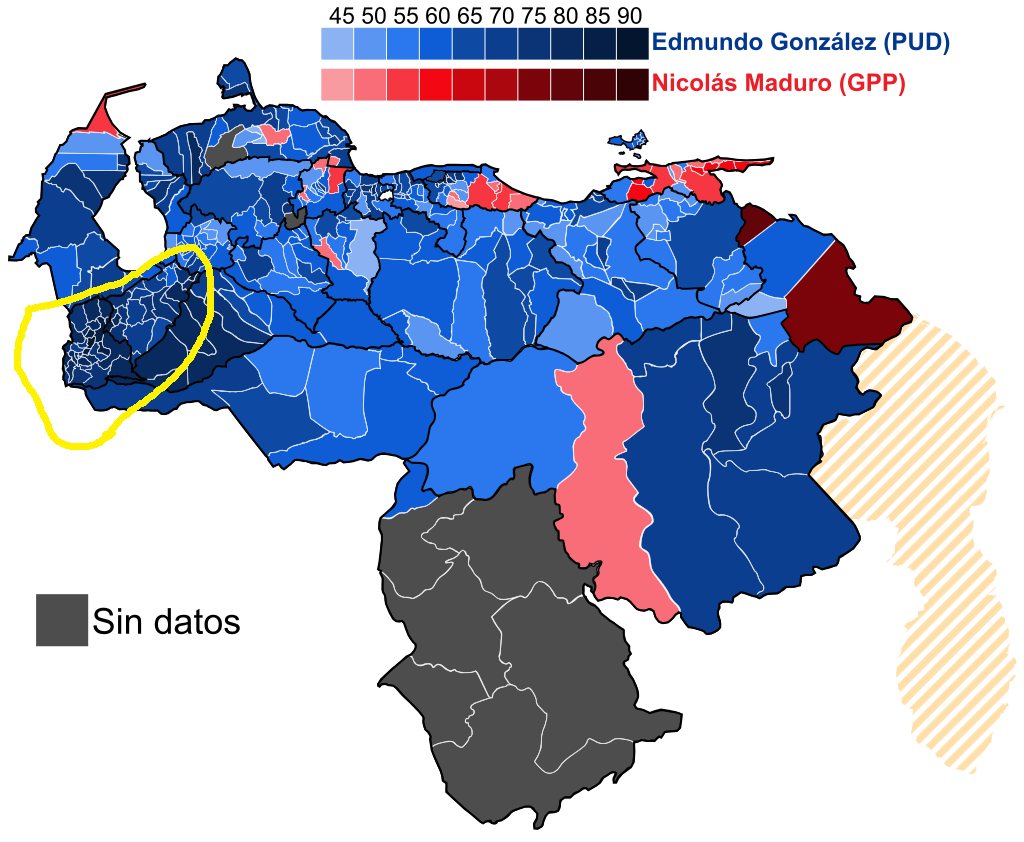

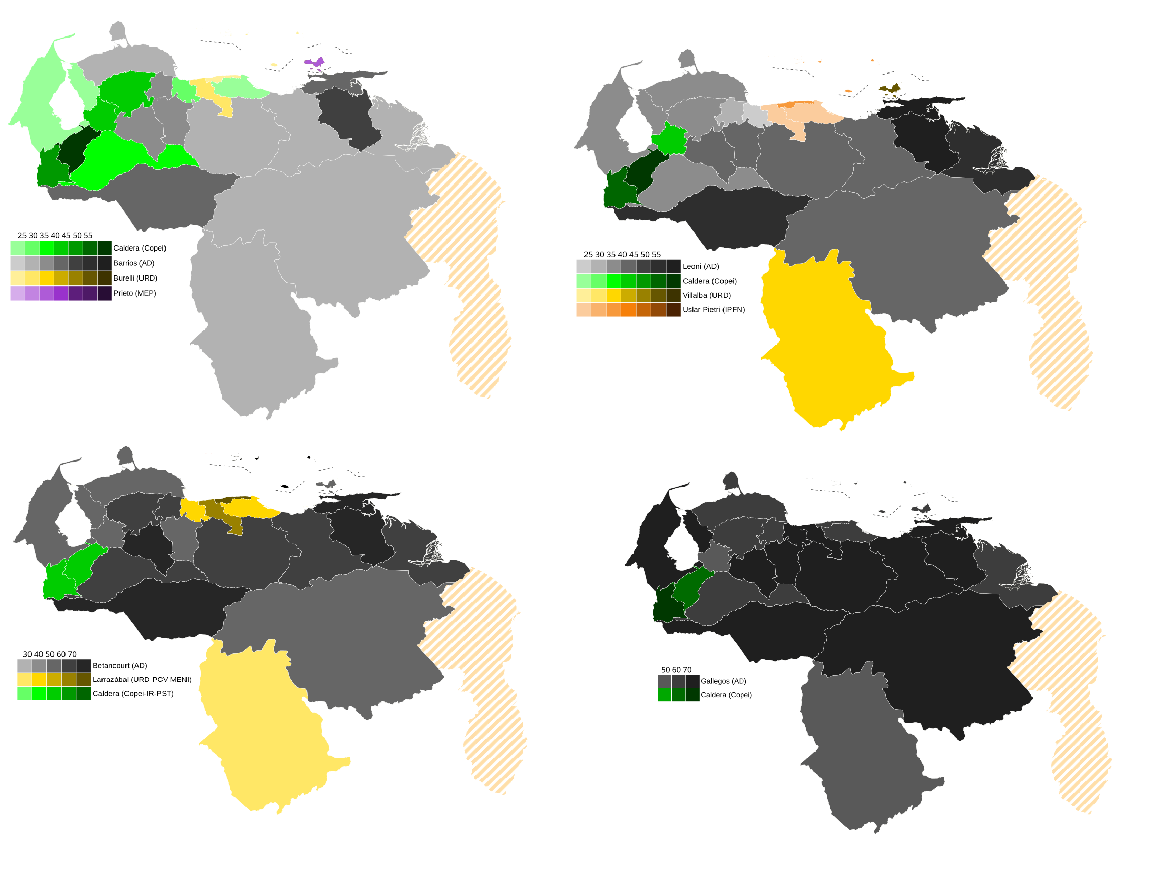

Here’s a map of the 2024 Venezuelan presidential election results according to the opposition Democratic Unitary Platform (PUD)4:

According to the PUD, Andinos voted overwhelmingly for González, with a 32 percentage point difference between the least pro-González state (Sucre, in the East) and the most pro-González state (Táchira).

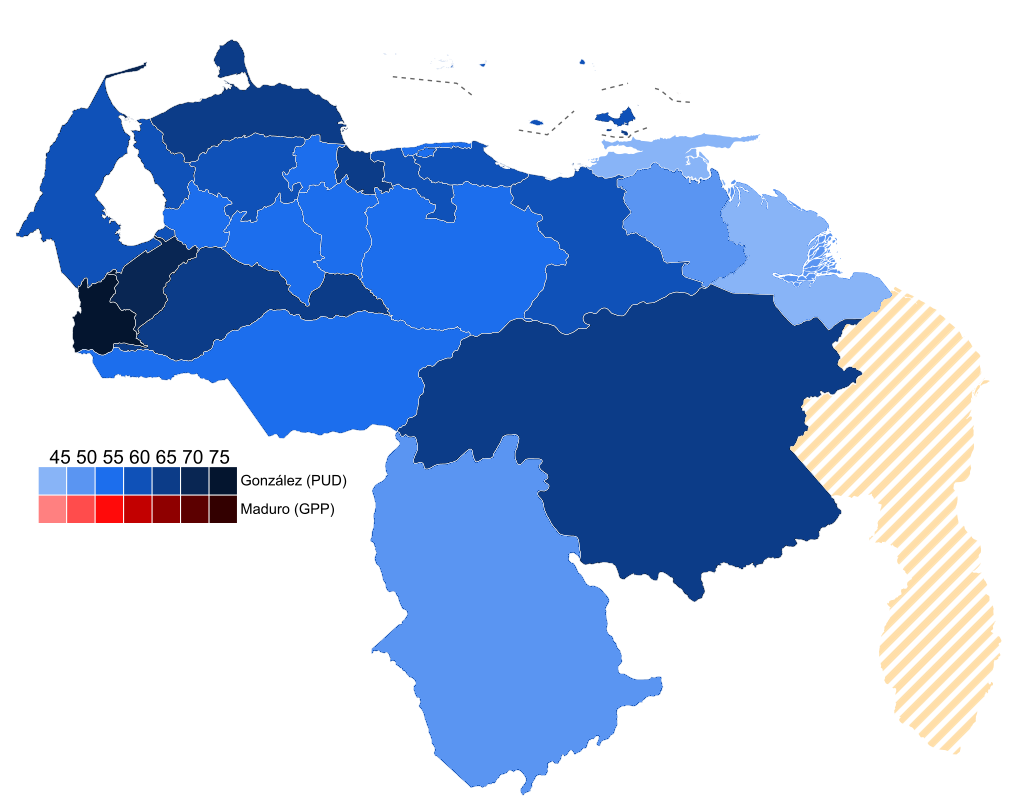

This is even clearer when looking at a map of results by state:

Geographic patterns in elections are nothing new. You can search the internet for maps of results by region (state) or district (county), and you will probably notice patterns for Brazil, the United States, France, etc. And you'll likely find several explanations offered for these patterns.

In the case of Venezuela, it would be interesting to explore whether this pattern has some basis in deeper cultural differences that are reflected in political preferences.

But first, we should ask if this is a persistent pattern, or just a recent phenomenon.

Here’s a map of the 2013 Venezuelan presidential election results:

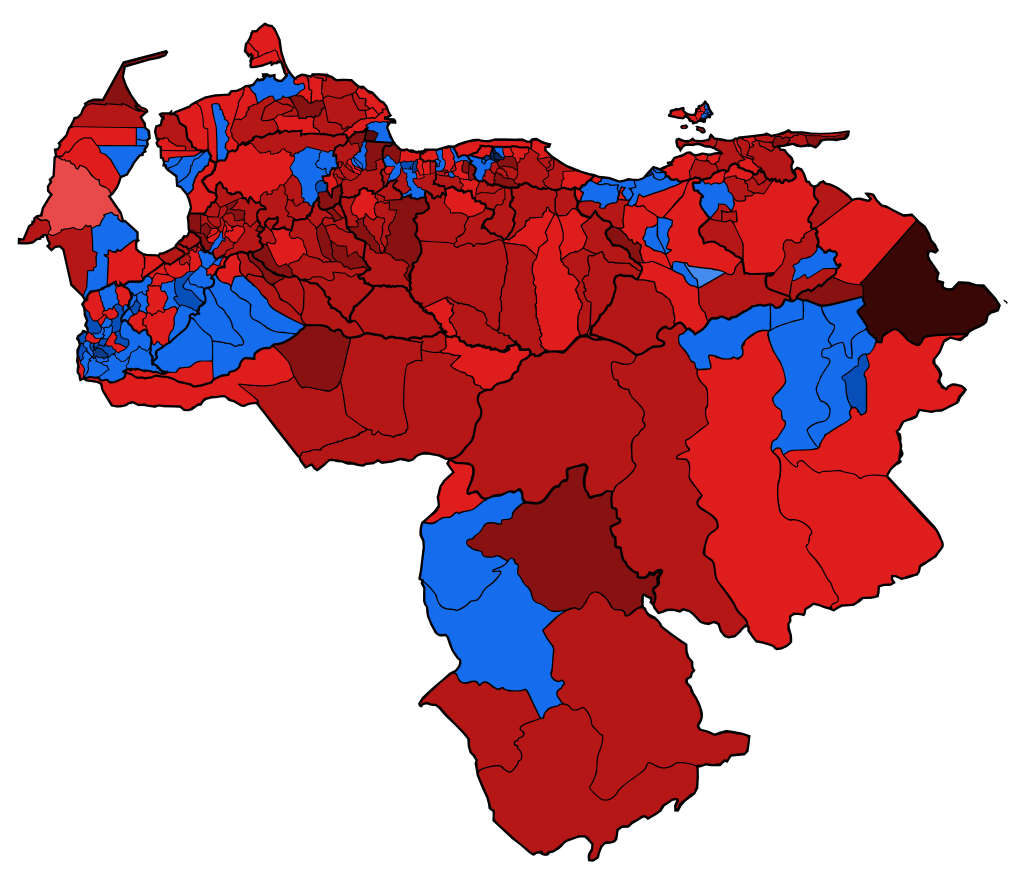

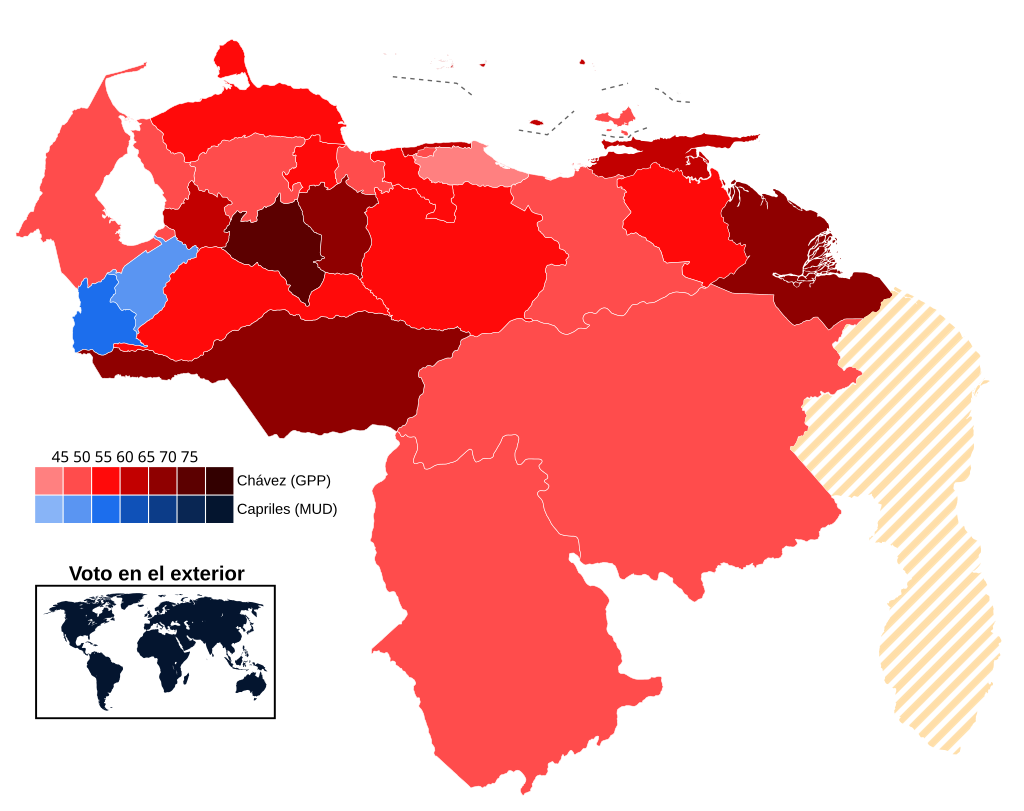

And of the 2012 presidential election, the last election won by Chávez, pitting the late Venezuelan leader against candidate Henrique Capriles:

And additional maps for various elections during the Chavista era:

Maybe these maps just reflect the fact that Andinos are anti-Chavistas - or less Chavistas - than other (Canarios?) Venezuelans?

To answer that question, let’s go back in time a little further.

A few older maps

Before the Chavista era (1999-present), Venezuela experienced what is typically referred to as the Puntofijo era (1958-1999), an era marked by political and social stability - with some hiccups.

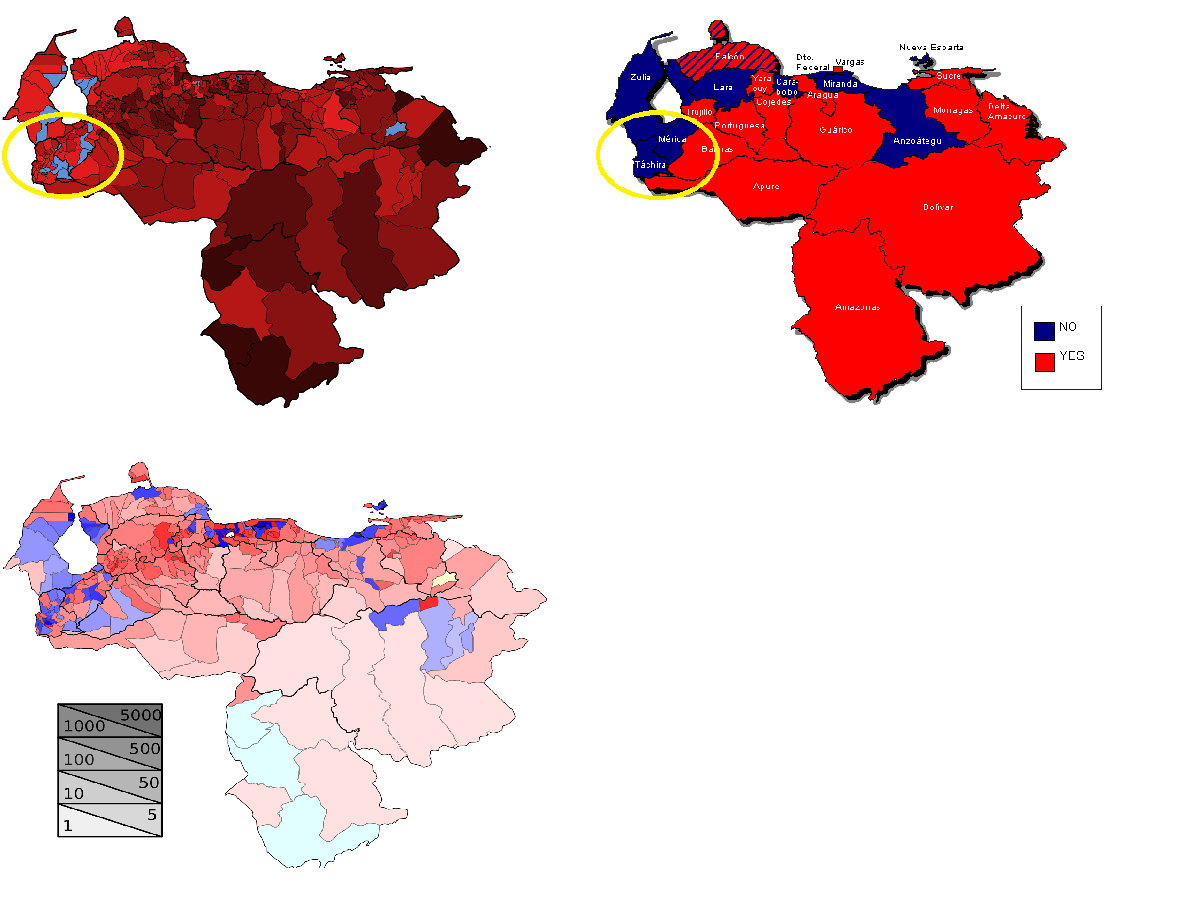

So, let’s look at some old election maps from the Puntofijo era5:

Once again, these maps show that the Andean region tends to vote in a distinct manner from the rest of the country.

Throughout this period - particularly before the 1980s - Andinos predominantly voted for the Copei party, a Christian democratic party commonly regarded as the right-wing half of the two-party system during the Puntofijo era. It’s main rival was the Democratic Action (AD) party, which could be considered the left-wing party.

Copei was founded and grew during the 1940s, after a period of dictatorial rule in Venezuela. It found particular success in the Andean region with the support of the Catholic church, of which Andinos were very fond.

In contrast to Andinos, coastal Venezuelans favored AD or parties further to its left, rather than Copei, as the previous maps show. Even when Copei, the less popular party of the two, finally managed to beat AD in 1968, the party’s candidate (Rafael Caldera) received a larger majority of the vote in the Andean region compared to other regions. Also, notice the level of support garnered by Wolfgang Larrázabal (in yellow), a communist leaning candidate, during the 1958 elections in the central Caribbean coast.

A few objections

In this post, I propose a hypothesis to explain the geographic disparities in voting patterns in Venezuela, but I acknowledge that it might be wrong. An obvious objection, evident just by looking at the initial maps, is that the Andean region is not such an outlier. There are other regions in Venezuela that seem to persistently diverge in their voting patterns.

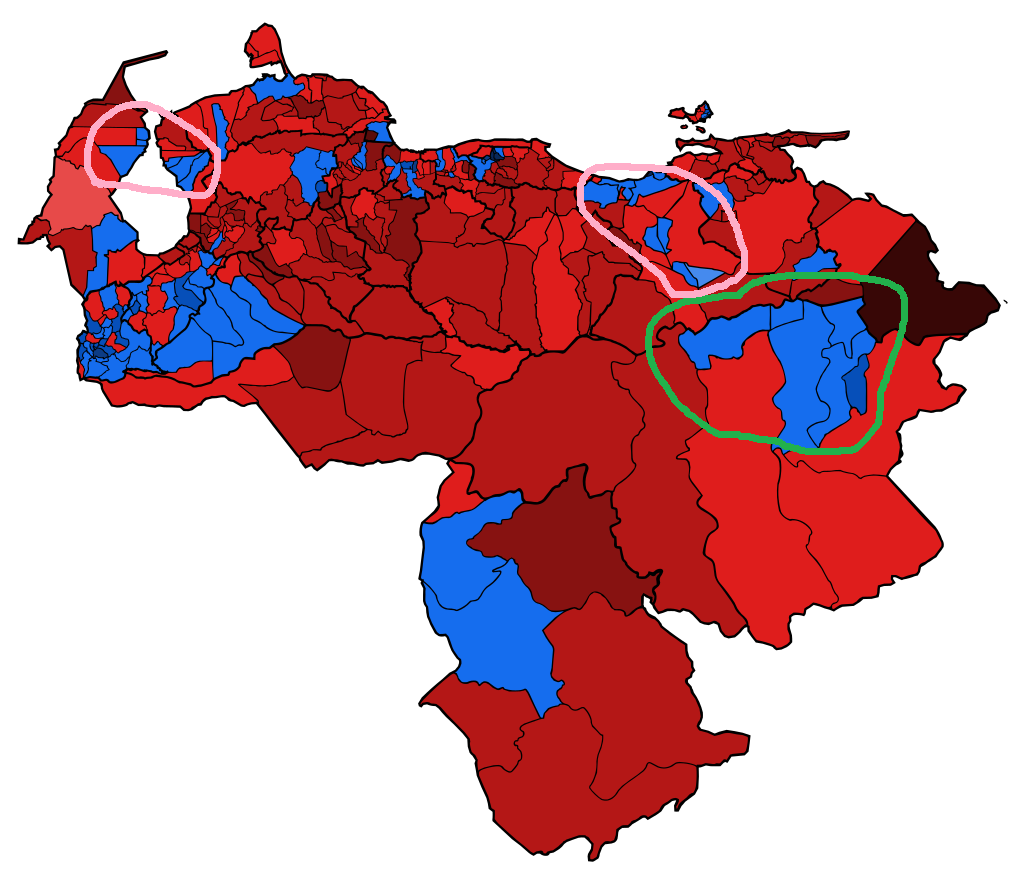

Here’s the 2013 Venezuelan presidential election results map again:

Notice that this time, I have circled other regions of Venezuela that seem to persistently diverge: two regions inside pink circles, and another region inside a green circle.

Let’s start with pink. The western pink circle encompasses the oil-producing region of Zulia, while the eastern pink circle is the oil-producing region of Anzoátegui. Together with the state of Monagas, located immediately east of Anzoátegui, these regions account for over 90% of Venezuela's oil production.

The green circle surrounds the mineral-rich region centered in Ciudad Guayana, Bolívar state. This area was responsible for some of Venezuela's main exports beyond oil, including iron, steel, and aluminum, in large part thanks to the plentiful energy produced by the nearby Guri Dam, which is the sixth-largest hydroelectric dam in the world.

These regions, in contrast to the Andean region, are very rich in natural resources.

Now, picture yourself as an average Venezuelan living in one of these regions.

You don’t work in the oil industry (or the steel or aluminum industry), but you benefit from residing in one of Venezuela's most economically vibrant regions, with high wages and a population with high consumption levels. Now imagine that this industry, the main engine of the region’s economy, becomes a shadow of it’s former self. Oil wells stop producing, steel mills close, etc.

Would you be less inclined or more inclined to vote for the Chavista candidate compared to other Venezuelans who have only experienced inflation, scarcity, insecurity, etc.?

This, I believe, is the reason why we don’t see Zulia/Anzoátegui/Bolívar’s pattern in older electoral maps, but only in the more recent maps.

Another objection is: but Trujillo state (the north-eastern most Andean state) is part of the Andean region, and the pattern is not clear for Trujillo. Point acknowledged.

As time passes and Venezuelans increasingly migrate from one area of the country to another, the cultural differences between different regions will tend to disappear. In particular, I think that the distinctions between Andean and coastal Venezuelans were more pronounced decades ago, and even centuries ago.

So my answer to the case of Trujillo is this: Trujillo is the least Andean of the three Andean states and it is the closest one to the rest of the country. Therefore, it is the state you would expect to be less Andino and more like the rest of Venezuela.

I doubt that I have thoroughly persuaded you of the existence of two clearly defined cultural regions in Venezuela, much less of the notion that these regions differ not only in their voting patterns but in many other ways as well. Ways that explain to a large extent the current predicament in which Venezuela finds itself.

But this post is already longer than I originally intended, so I’ll leave further comparisons between Andinos and other (Canarian) Venezuelans, and further explorations of their origins, for a future post.

(UPDATE: I wrote a follow-up post discussing Colombia.)

If you've been keeping up with the news from Venezuela and have some knowledge of Cuban or Venezuelan history, you might recognize some of those surnames: Machado, Batista, Betancourt.

Also states located immediately to the south of the Caribbean coast and far to the east of the Andean region: Guárico state and Monagas state.

The fancy word is ethnogenesis.

I haven’t been able to get my hands on a map of the official results according to the Venezuelan CNE. If you know where I can find it, please let me know in the comments

The 1947 Venezuelan presidential election was not part of the Punto Fijo era. It took place during the last years of the Andean hegemony era.