On the effects of the Counter-Reformation

A Counter-Narrative to a recent article by Cremieux Recueil on the Counter-Reformation

I was recently made aware of a job market paper by Matías Cabello titled The Counter-Reformation, science, and long-term growth: a Black Legend? through Cremieux Recueil’s summary and analysis of it:

I don’t intend to waste your time with yet another summary of Cabello’s paper - there’s another good overview by Alice Evans here. Instead, I’ll just quote the paper’s abstract and a few select paragraphs from Cremieux’s post to give a sense of what the paper is about, before discussing the concerns I have with it:

Is it true that the Catholic reaction to Protestantism - the Counter-Reformation - led to scientific and economic decline for hundreds of years? Introducing biography-based evidence, I show that Catholic and Protestant European cities long shared comparable trends of scientists per capita. But after imposing intellectual control in response to the Reformation, Catholics experienced a dramatic scientific collapse coinciding with the Counter-Reformation’s different timing and intensity across cities. Reassuringly, science began to recover after the Counter-Reformation was dismantled, but the recovery stagnated when Counter-Reformation-rooted institutions were revived centuries later against new ideological threats. Although it has largely vanished by now, the gap in science that emerged during the Counter-Reformation was enormous, lasted centuries, and helps explaining Europe’s unequal modern economic growth. Protestants also tried to impose their own bigotry but lacked sufficient coordination and authority. Had they been more effective, modern science and sustained economic growth might have never taken off.

As Cremieux mentions in his piece, attributing the differences in economic growth and social development - of the kind we associate with modernity - between Protestant Europe and its offshoots versus Catholic Europe and its former colonies to the effects of the Protestant Reformation is nothing new, and seems to be well established by an extensive body of literature:

The momentous character of the Protestant Reformation is hard to doubt. Scholars have noted the boons that came from Protestants’ promotion of mass literacy, they’ve suggested that Protestant refugees enriched the lands they traveled to and that Protestantism is a fairly democratic faith, and its corresponding promotion of communal, locally participative government might have helped it to promote creative endeavors. Similarly, researchers have noted that Protestant church ordinances and the need to establish state management capabilities aside from the traditional institutions of the Catholic Church led to greater public service provisioning and investments in state capacity which attracted intellectuals to Protestant towns and cities and also promoted growth in Protestant cities with said laws in general. Others have made the even stronger claim that Protestantism allowed for the creation of the institutional fundaments of industrialization, full-stop.

Cabello’s paper suggests that the Counter-Reformation was the causal mechanism for the stagnation, and even decline, of scientific output in Catholic Europe compared to Protestant Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries.

Up until the Counter-Reformation, Europe’s Protestant and Catholic cities were on a similar enough trajectory when it came to the production of scientists, but suddenly growth overall was curbed across the continent, leading to a slowdown for both, with total stagnation in the Catholic cities.

The mechanism involves the stifling of intellectual activity, constraints on free inquiry, and generally making the lives of scientists harder.

Because they were not under the rule of the Habsburgs or directly governed by other Catholic Church-supporting factions that would have imposed literature bans, university control, intellectual isolation and conservatism, inquisitorial activity, and so on, they didn’t scientifically decline.

The scientific decline of Catholic Europe was driven by the Catholic Church, the Inquisition and the Spanish Empire1.

Cremieux also highlights the role of Protestantism not only in fostering human capital but also in drawing highly skilled individuals to specific European cities and regions. What benefit does it bring to a locale to produce and educate brilliant minds, if they subsequently migrate to a more tolerant environment?2

This shift of human capital to Protestant Europe was not just one of Protestantism creating more human capital or allowing people to express their views more freely—both of which were real parts of the equation here—, but also of individuals with high human capital migrating to Protestant cities and states. More specifically, the right tail of human capital disproportionately migrated to those cities that enacted church ordinances, above and beyond the general positive impacts on city growth. The case of the Low Countries (Benelux) provides a clear case study in the simultaneous effects of all of these dynamics.

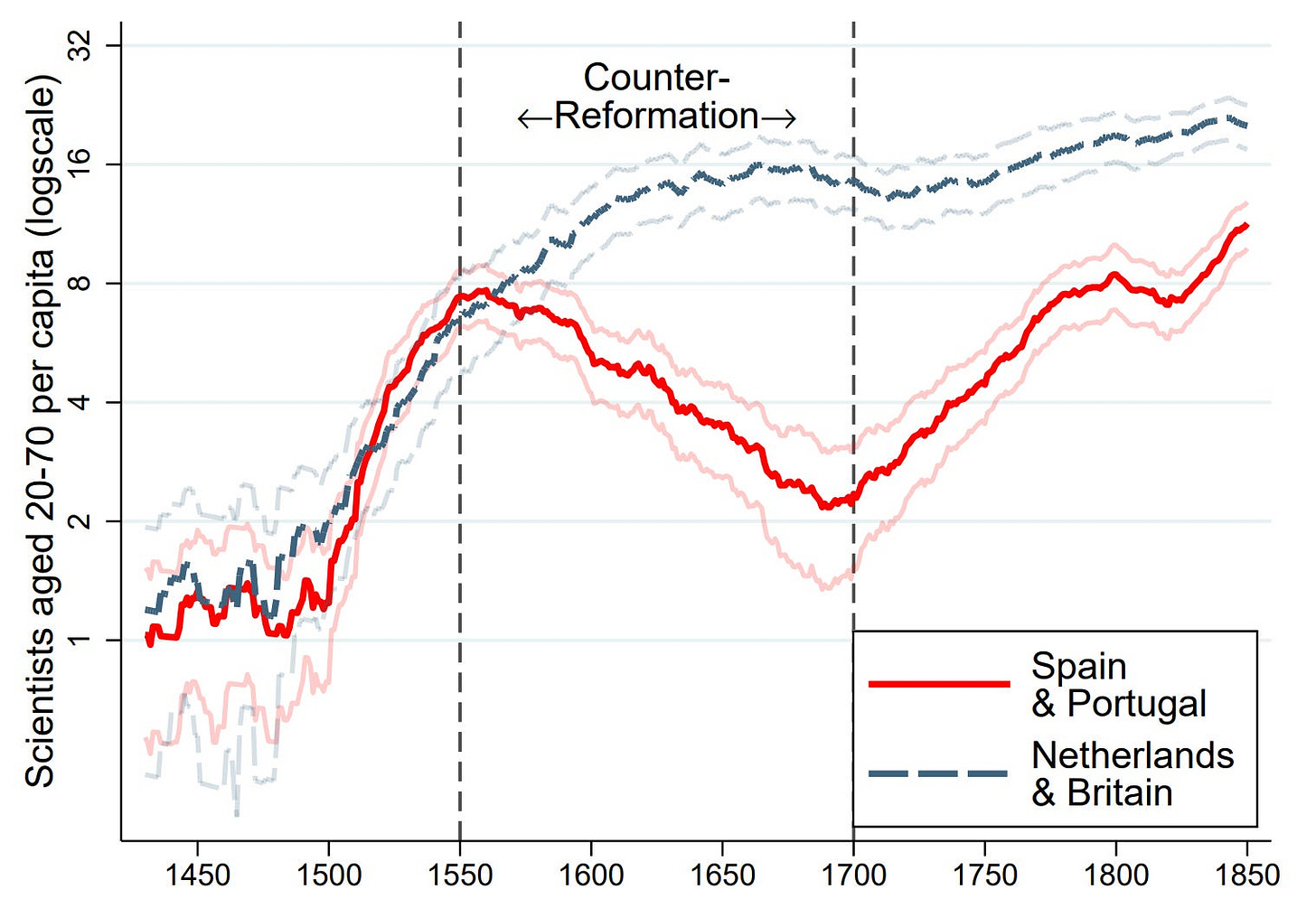

By examining trends in scientific productivity, measured by the number of active scientists in any given year, Cabello argues that key historical events during the Counter-Reformation led to a noticeable divergence in scientific output between Catholic and Protestant lands.

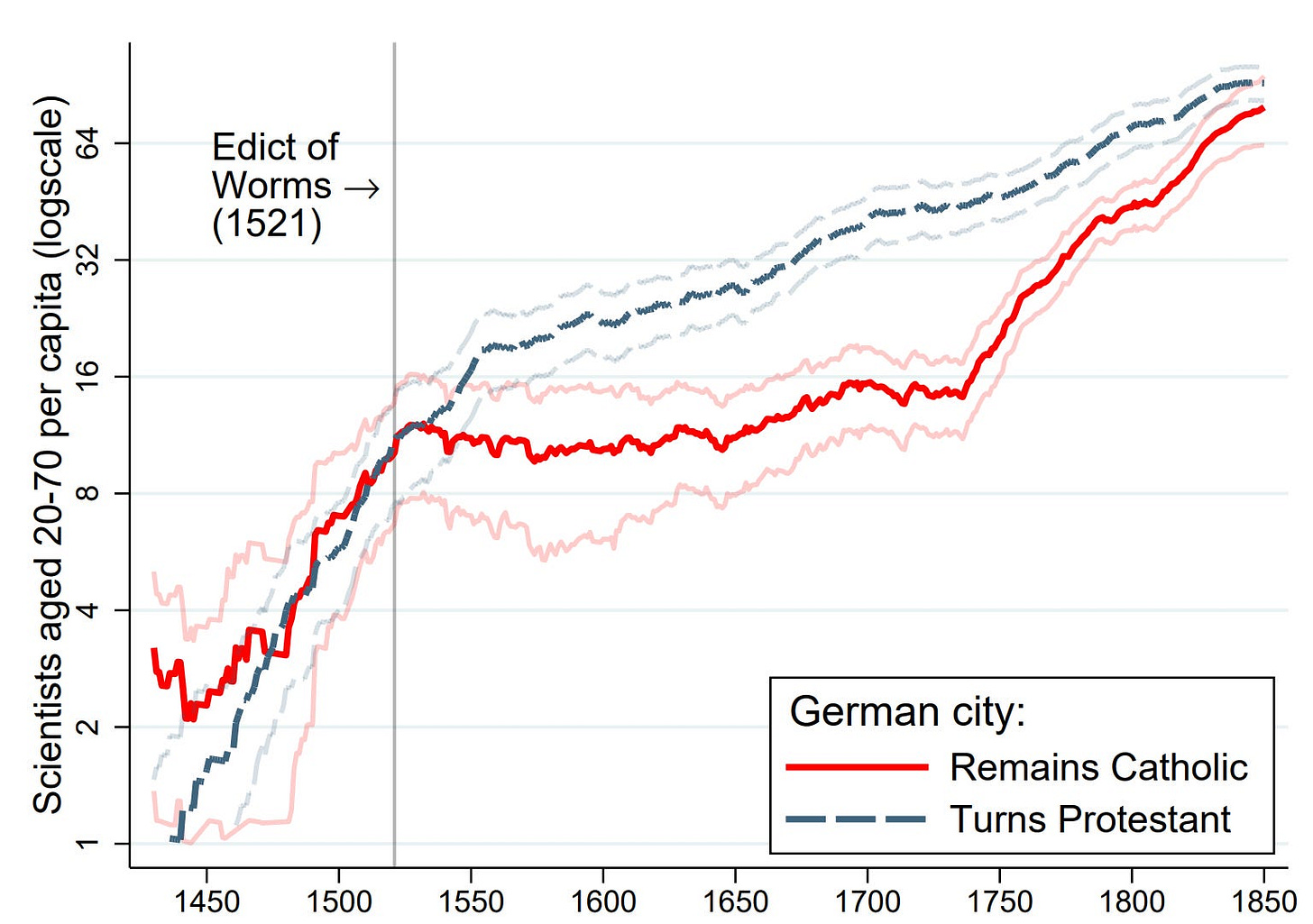

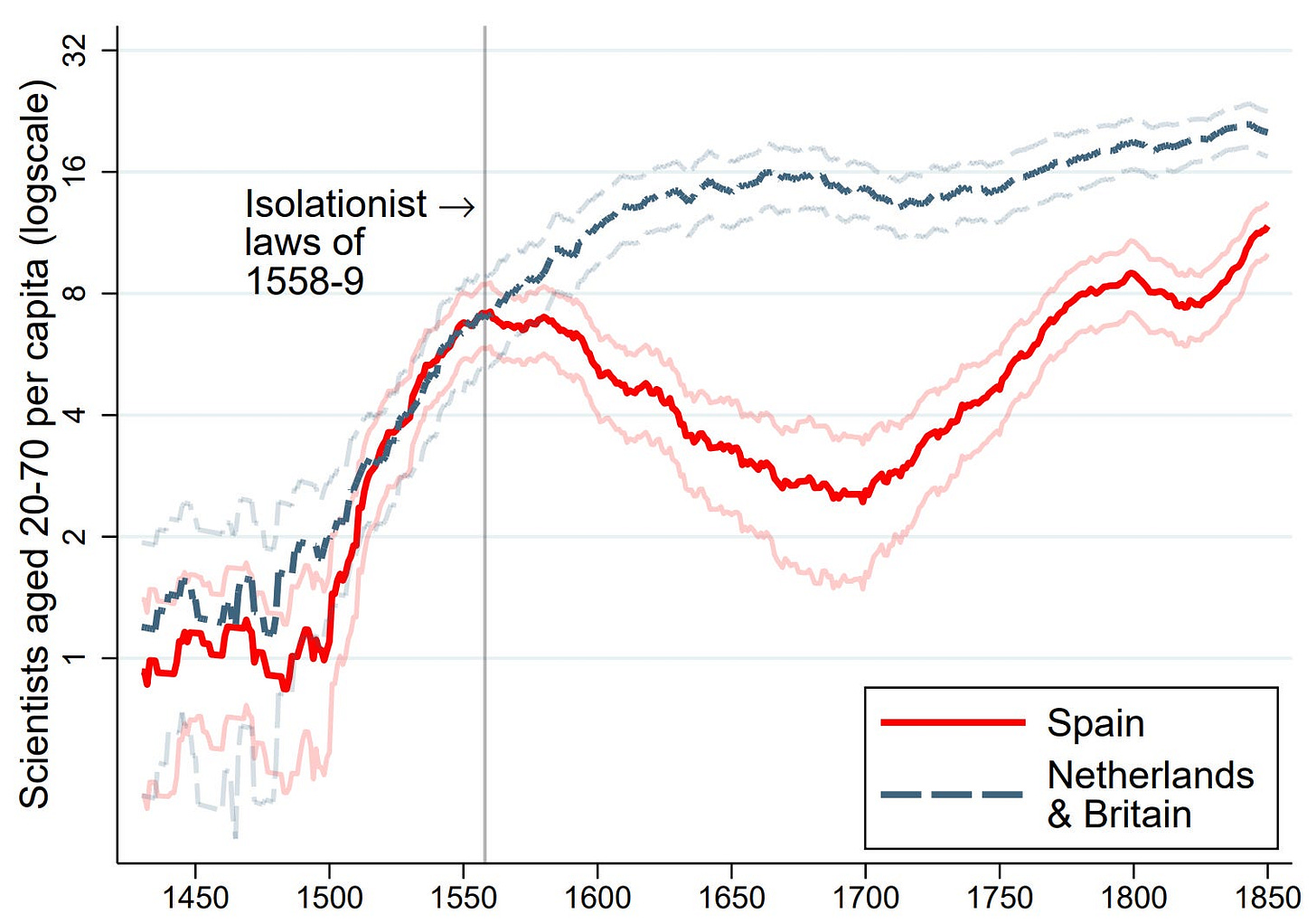

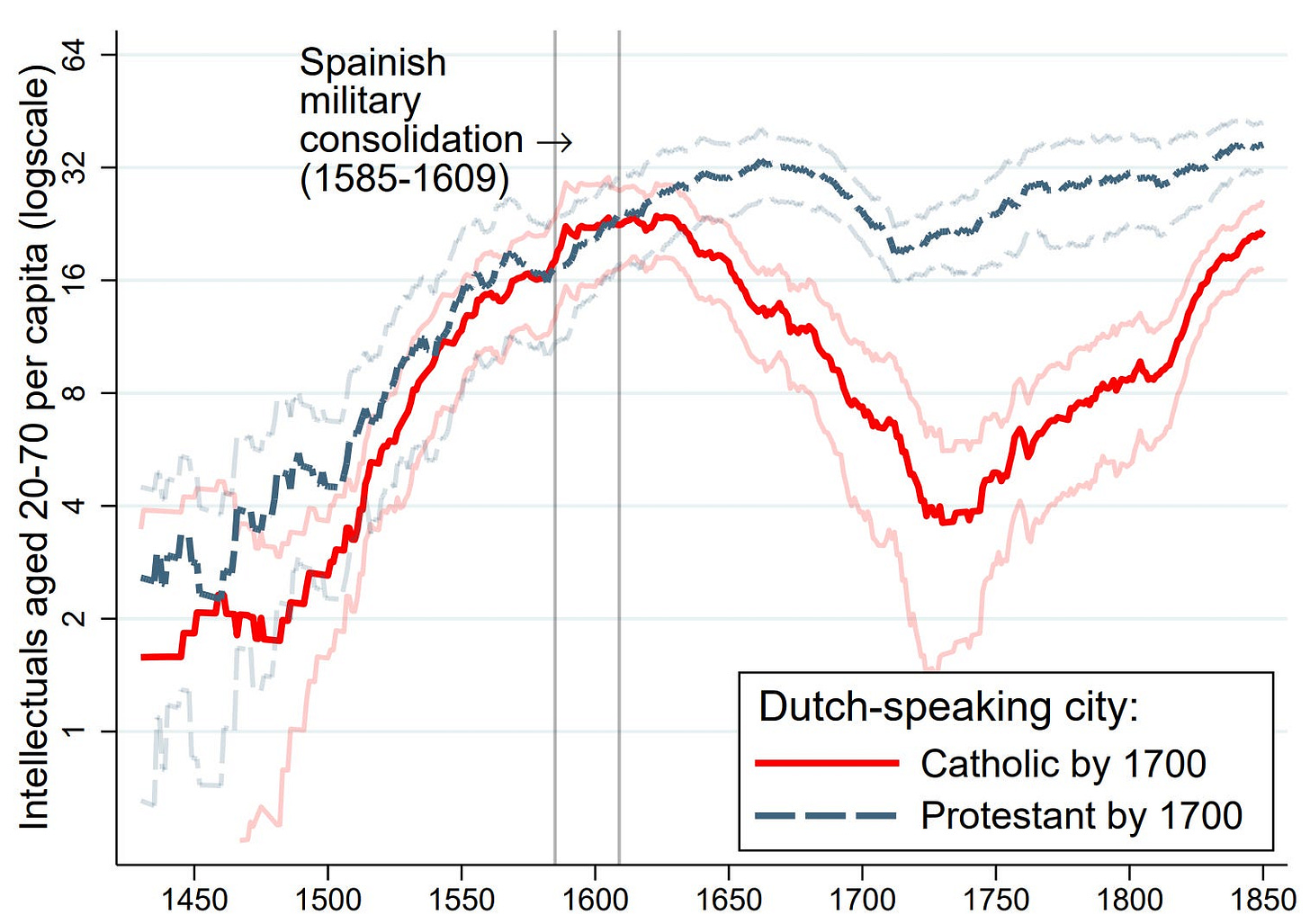

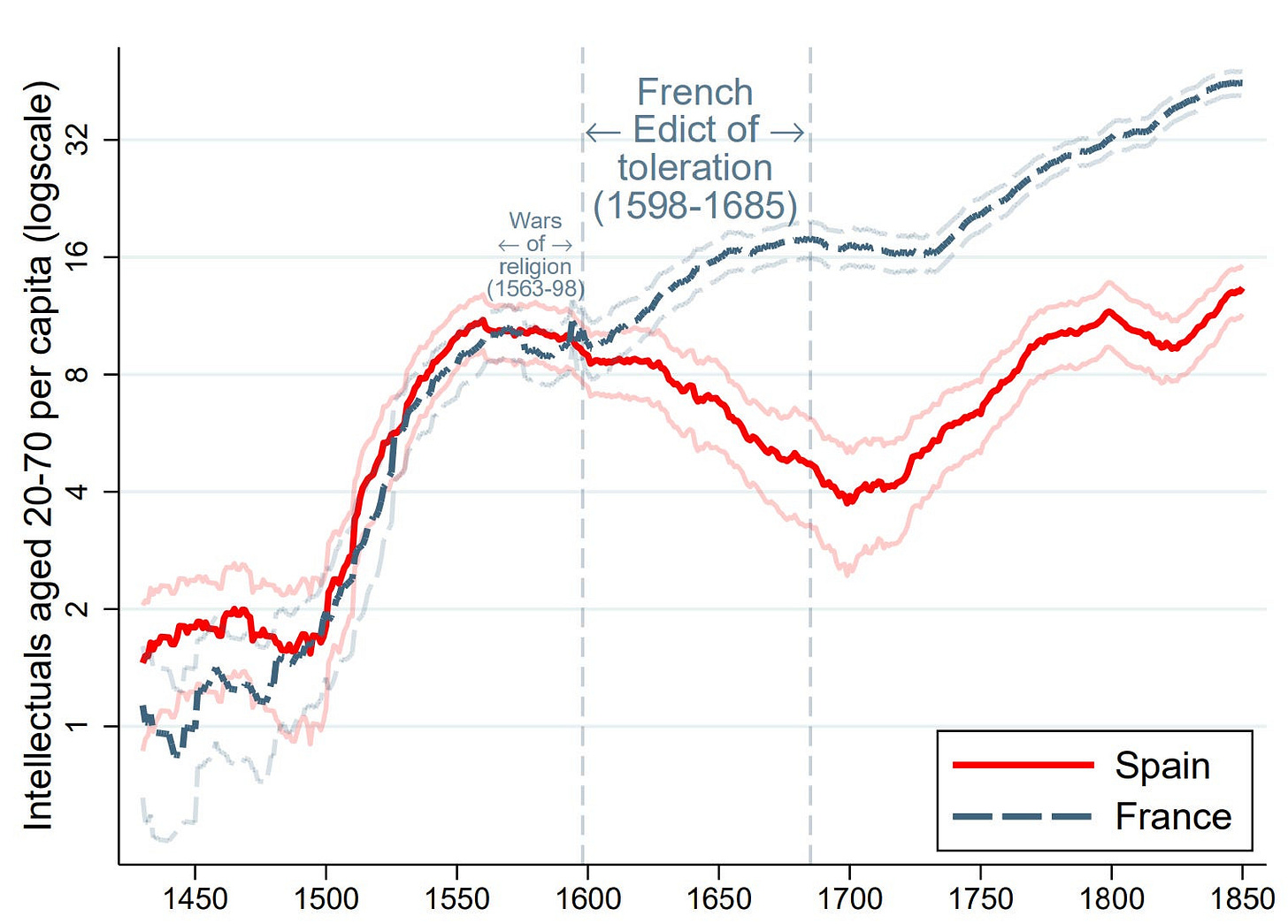

We know the Catholic Church exerted its pernicious influence at different times in different places, and that it did so for different reasons that suggest even more strongly that it was always a possible threat to European progress. In Germany, the separation between Protestant and Catholic cities occurs shortly after the Edict of Worms and right around the Diet of Speyer I mentioned earlier… right after Spain discovers a multitude of Protestant cells in the country, prompting it to implement isolationist laws… When the Spanish reasserted themselves in the Low Countries… [And] France managed to substantially but not wholly save itself from the madness of the Catholic Church by issuing the Edict of Nantes

And here are four charts that illustrate the impact of historical events on scientific productivity, as referenced by Cremieux in the preceding quote:

At this point, I have to make a clarification about Cabello’s metric of scientists per capita. Due to the scarcity of data on actual scientific activity, his definition of scientists per capita is based on the number of living scientists within the age range typically associated with peak scientific productivity.

To investigate whether science was affected by the Counter-Reformation, this paper proxies scientific activity by the number of “scientist per capita” (to be defined below) at the city-year level, based on biographical data gathered from Wikidata…I use the incidence of such biographies to proxy scientific and intellectual activity across time and space…I proxy activity over time using a researcher’s age combined with the empirically-observed distribution of the age of scientific genius during the analyzed period. With regard to activity locations, I proxy them using birth and death places3

If I understand Cabello correctly, a scientist born in 1550 and who died in 1595 will add to the metric between the years 1570 and 1595. A scientist born in 1600 and deceased in 1680 will be included in the metric between the years 1620 and 1670.4

This means that some anti-scientific policies should only impact scientific production in a delayed manner. This would be the case of measures that hinder the recruitment of new scientists (e.g. disruptions to early education) or those that make a career in science less appealing. By reducing the anticipated pool of future scientists, these policies should affect scientific production a decade or two later.

On the other hand, policies which hinder scientists' daily work or financial stability (e.g. closure of universities), would likely have an almost immediate effect. And policies that obstruct scientists ability to collaborate with each other (e.g. restrictions in scientific collaboration with foreign scientists) might have a medium-term effect.

So, if I understand the scientists per capita metric correctly, two of the previous four charts don’t make sense.

The charts

The first chart, Figure 6a (Edict of Worms), should exhibit a slightly delayed decline in scientific production in Catholic German cities, assuming Catholic authorities indeed acted against scientists and discouraged scientific production. But Cabello doesn’t provide evidence for the suppression of science during the early decades of the Reformation in Germany.

So, why does the trend diverge between Catholic and Protestant German cities beginning around 1530-1540? I’ll come back to this shortly.

The second chart, Figure 6b (Isolationist laws of 1558-1559), is also problematic. The isolationist policy of Philip II of Spain exemplified in the 1559 decree prohibiting Spanish students from studying abroad, was complemented by the addition of scientific books to the Inquisition’s index of 1559 (Figure A1).

These legal measures likely hindered Spanish scientists’ ability to collaborate with their foreign counterparts and stay up to date regarding the latest scientific developments, but it seems unlikely that their effect was felt immediately, as the chart implies. More plausibly, the effects would have manifested over years, if not decades.

Bourgeois scientists

Regarding the third chart, Figure 6c (Spanish military consolidation), I find no issues with it, though I believe it holds little relevance in substantiating Cabello's thesis. It is widely acknowledged that tens of thousands of Southern Dutch, predominantly from bourgeois or skilled worker backgrounds, migrated northward following the Spanish suppression of the Dutch Revolt in what is now Belgium.

Some returned to Roman Catholicism but many moved north and ended what had been a golden century for the city. Of the pre-siege population of 100,000 people, only 40,000 remained. Many of Antwerp's skilled tradesmen were included in the Protestant migration to the north, laying the commercial foundation for the subsequent "Dutch Golden Age" of the northern United Provinces.5

However, after the revolt of the seven northern provinces (1568), the Sack of Antwerp (1576), the Fall of Antwerp (1584–1585), and the resulting closure of the Scheldt river to navigation, a large number of people from the southern provinces emigrated north to the new republic. The centre of prosperity moved from cities in the south such as Bruges, Antwerp, Ghent, and Brussels to cities in the north, mostly in Holland, including Amsterdam, The Hague, and Rotterdam.6

This was a massive migration. The 60,000 individuals who reportedly migrated from Antwerp alone constituted approximately 3% of Belgium's total population at that time.

And this was the segment of society from which one would expect the majority of scientists to emerge. Spanish military consolidation in the Southern Netherlands did not trigger the establishment of the Inquisition there, but it did deprive Belgium of a large part of its inherent recruitment pool for future scientists.

There certainly seems to be a causal link between the consolidation of Spanish rule in the Southern Netherlands and its relative scientific decline compared to the Northern Netherlands, but it’s doubtful that this decline can be attributed to Spanish rule - without the repressive tool of the Inquisition - and the influence of the Catholic church.

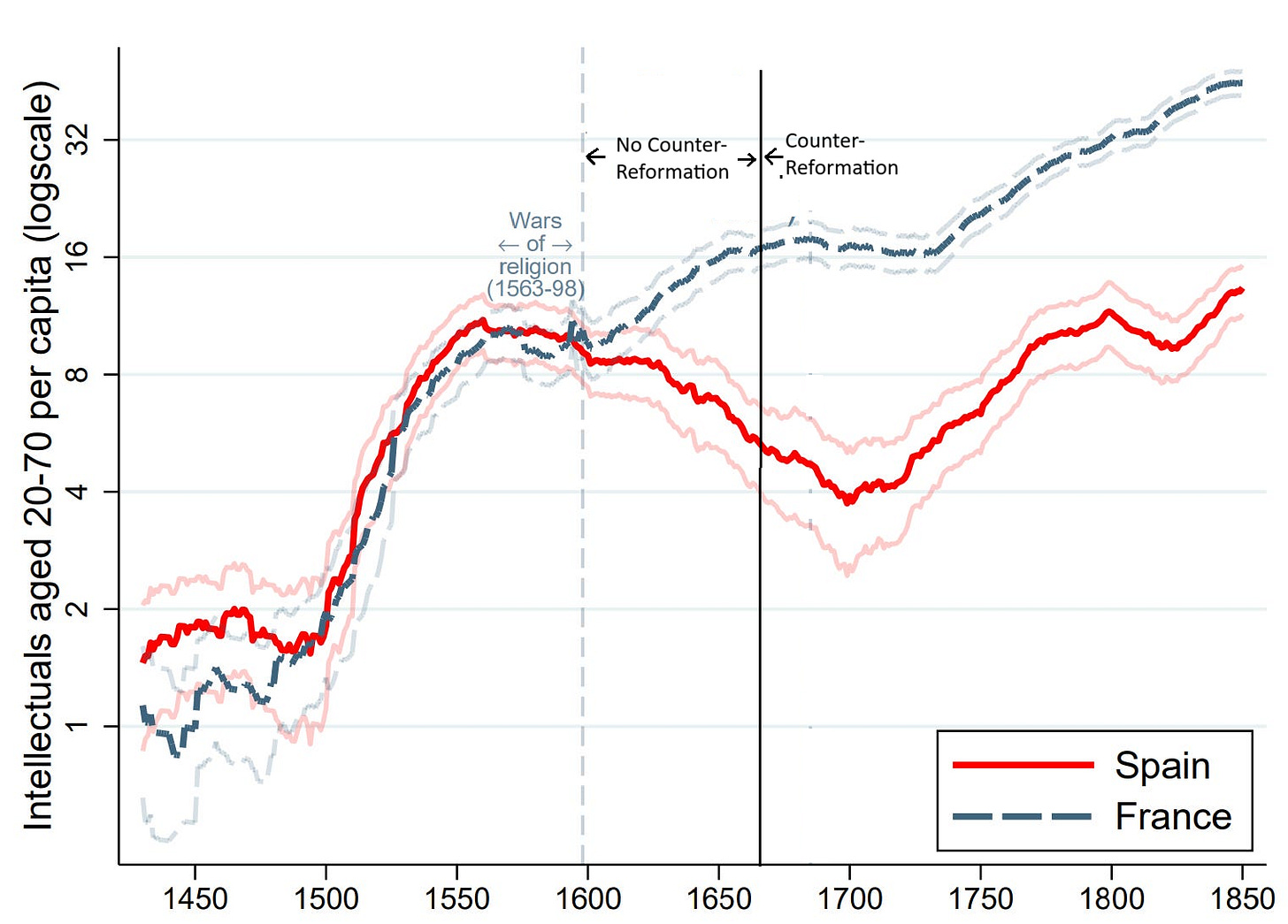

Finally, the fourth chart (Figure 6d, French Edict of toleration) purports to show the impact of the Edict of Nantes, granting toleration of Protestantism in France, by showing how scientific production diverged between Spain and France during the 17th century.

My objections to that interpretation are:

The edict of Nantes did not abolish the French Inquisition, which barely had any activity at all during the late 16th and 17th centuries.

In place of the French Inquisition, the French state could have taken measures to suppress heresy, but it didn’t, except for brief intervals during the 1560s and 1580s.

If we look at the period preceding the Edict's publication, the most parsimonious explanation for the stagnation in French scientific production during the second half of the 16th century appears to be the disruptions caused by the French Wars of Religion. Irrespective of whether this was the main cause, the stagnation during that period - shared by Spain - demonstrates that scientific decline can occur due to factors other than suppression by religious authorities.

What other factor could explain the divergence between France and Spain during the 17th century?

The Society of Jesus

I agree with Cabello’s general thesis that the Counter-Reformation was behind the decline of Spanish scientific productivity during the 17th and early 19th centuries. Though perhaps I should say ‘declines’, given that most of the 18th century was a period of relative increase.

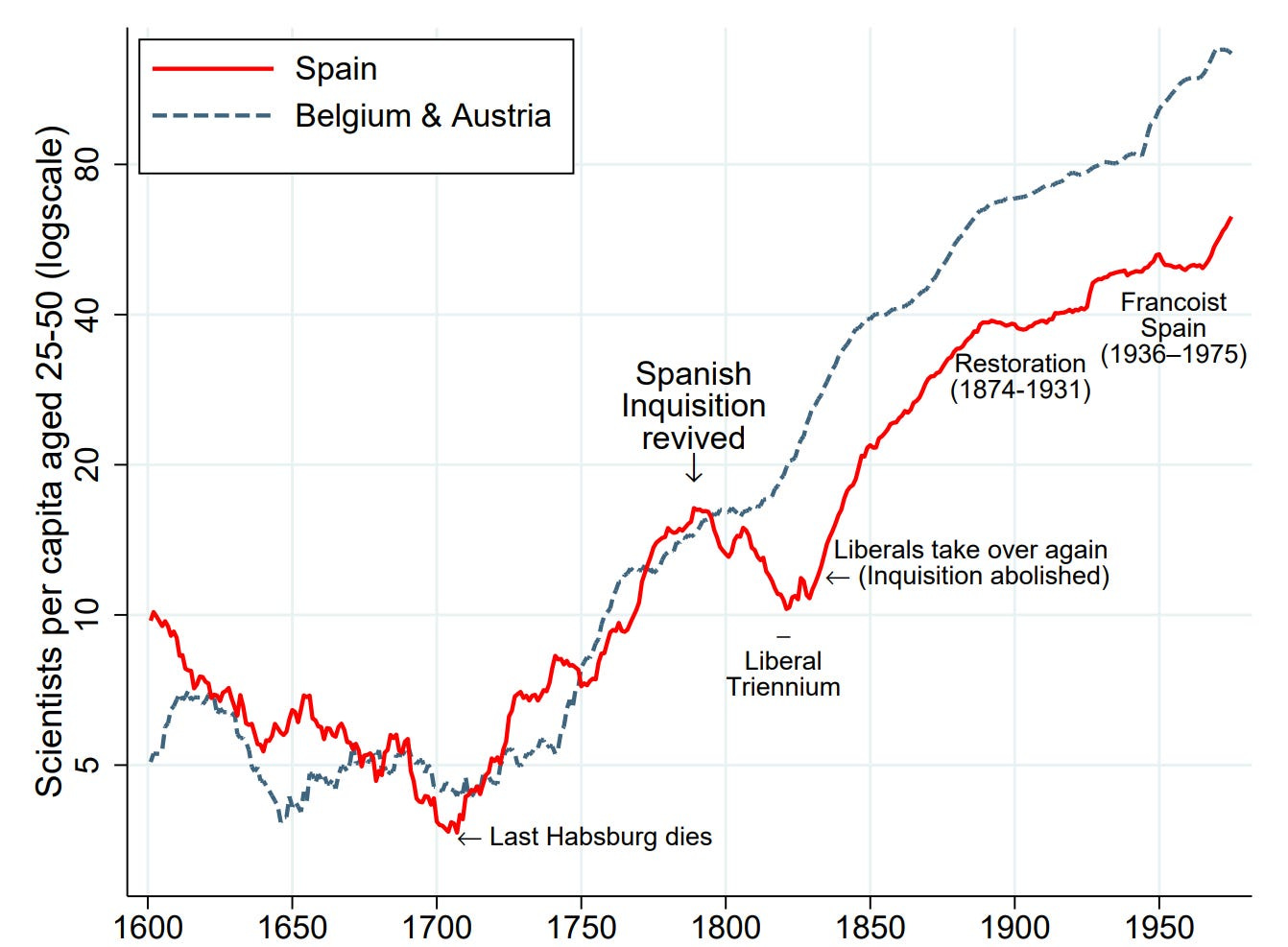

This is clearly evident in Cabello’s Figure 8:

Cabello attributes the Spanish scientific decline in the late 18th and early 19th centuries to a revival of the Spanish Inquisition.

Yet, to the best of my knowledge, there is no evidence of the Spanish Inquisition banning scientific literature in the late 18th century as far as I’m aware. Only political literature was banned.

In fact, by the late 18th century, the Inquisition seems to have become less active and less repressive: its powers were reduced7, the centuries-old prohibition against vernacular translations of the Bible was lifted (1782)8, and its Grand Inquisitors were increasingly chosen from among the enlightened classes of society9:

In the seventeenth century and most of the eighteenth, the grand inquisitors were not, strictly speaking, mediocre men, but they lacked personality…Not until the last years of the eighteenth century do we find, in Cardinal Lorenzana, a grand inquisitor who returned to the great cultural tradition of men such as Cisneros. Lorenzana was the very epitome of the kind of enlightened prelate much beloved in the time of Charles III. He began his career as archbishop of Mexico, in which capacity he was extremely active not only in encouraging religious teaching but also in promoting interest in scientific knowledge. In 1770, for example, he published a richly documented and illustrated history of New Spain…He funded libraries, took an interest in regional antiquities, published a variety of works on Gothic and Mozarabic rituals, and financed the publication of the works of Saint Isidore of Seville. Lorenzana could hardly be branded a narrow-minded and fanatical inquisitor.

The inflection point towards enlightened inquisitors seems to have occurred during Felipe Beltrán’s tenure (1775-1783)10:

While he was in office, the court applied the last two tortures by fire, only sixteen public penitentiaries were given and the poet Tomás de Iriarte was able to escape an accusation of irreligion and Voltairianism with a very light sentence, practically an acquittal.

Though even before then, the Inquisition was well aware that forbidden books were being brought into Spain, and its reliance on spontaneous denunciations, which were no longer forthcoming, rendered book censorship largely ineffectual11.

The sole evidence that I can find of a revival of the Inquisition in late 18th-century Spain is the publication of a new Index of forbidden books in 1790 - the last one had been published in 1747.

The main motivation behind the publication of a new Index appears to have been the perception that the 1747 Index was pro-Jesuit and anti-Jansenist12. The Jesuits did not simply fall out of favor with the Spanish court; they were unceremoniously expelled from Spain and all its possessions in 176713.

The Inquisition had been contemplating the publication of a new Index since 1782, without any results. However, it had already resolved to exclude certain books from this Index, heeding the 'fair and judicious objections' on the part of the 'judicious and well-informed public' regarding these works14. The judicious and well-informed public was not alone in wanting to end the censorship of science books15.

When the Inquisition finally published its new Index, likely prompted by the upheaval of the French Revolution, it included forty additional works, all but one pertaining to the sessions of the French Estates-General or the Revolution itself16.

There is no evidence for a revival of the Inquisition in late 18th-century Spain.

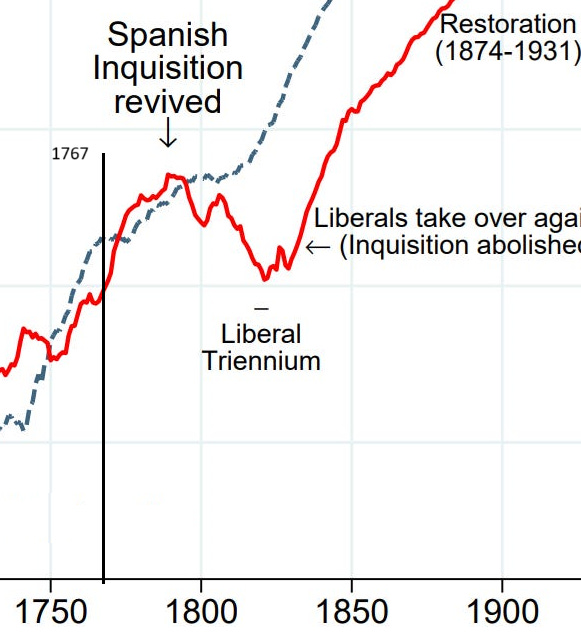

What’s the most likely reason for Spain’s late 18th-century scientific decline then? Let’s zoom in on Cabello’s Figure 8 (from Appendix C17), which I have previously shown.

I have marked the year 1767 with a new line, coinciding with the Jesuits’ expulsion from Spain. If you trace about a decade forward from this event, you'll see a shift in the trend, moving from a steep ascent to a slow rise. You will also notice that approximately 20 to 25 years after the suppression of the Jesuits, Spain’s steep scientific decline begins.

This is in accordance with what you would expect considering the enormous weight that the Jesuits had in running and conducting Spain’s educational establishment. Ten years after the closure of colleges and universities, one might anticipate the onset of effects on scientific productivity. Furthermore, 20 to 25 years after the departure of Jesuit teachers and scientists - remember, the chart shows scientists aged 25 to 50 - one might expect the next generation of scientists to be significantly reduced in numbers compared to their predecessors.

The most parsimonious explanation for Spain’s late 18th century and early 19th century scientific decline is the expulsion of the Jesuits18.

Notice that a first “valley” seems to occur around 1800, with the nadir of the decline occurring around 1820-1823, coinciding with the Spanish Liberal Triennium. A child aged 8 to 10 in 1767 would reach 41 to 43 years old by 1800, a bit higher than the average between 25 and 50 (37.5).

I’ll quote Cremieux again now:

Because, in the Malthusian era, knowledge was extremely fragile and small elite contractions could disrupt its transmission entirely19

To expel or not to expel

The Society of Jesus, founded in 1540, was a product of the Counter-Reformation. Some would argue that they were instrumental in driving the Counter-Reformation across large parts of Europe.

They took to heart the Counter-Reformation’s goal of replacing the traditional clergy, frequently criticized for greed and ignorance, with a new cadre of well-educated priests. Its founder, Ignatius de Loyola, was a student at the University of Paris when he gathered around himself a group of fellow students who would later assist him in establishing the new order. This group included his successor Diego Laynez, who acted as the pope’s theologian in the Council of Trent, which initiated the Catholic Counter-Reformation.

The third Superior General of the order, Francis Borgia, was an enlightened aristocrat - serving as a diplomat, viceroy, and also composer of liturgical music. Borgia would go on to found a dozen colleges, anticipating the strong Jesuit commitment to education, with more than two hundred colleges established across Europe.

Here’s a map depicting Jesuit colleges throughout Europe circa 1650:

At first glance the high concentration of Jesuit colleges in Spain might not be apparent. But this perception is due to Spain's relatively low population density20.

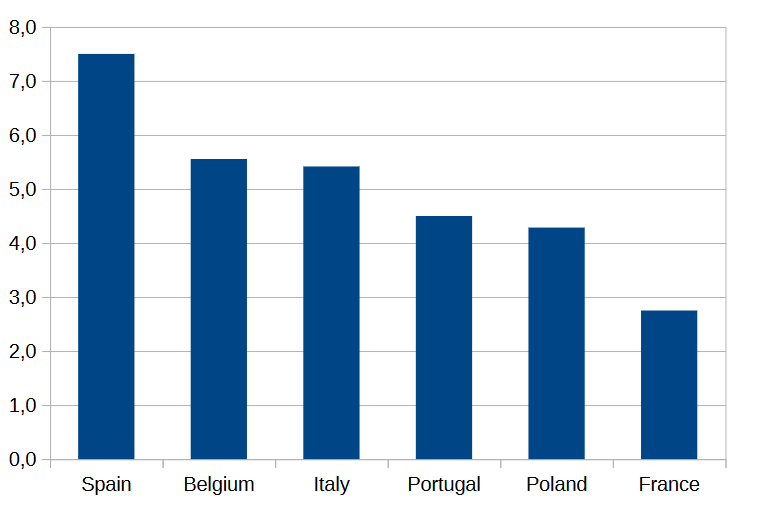

Bellow are the rates of Jesuit colleges per million inhabitants for major Catholic European countries around 1650:

Spain was by far the European country most reliant on the Jesuits for running its educational system, yet the cases of Belgium and Italy also merit attention.

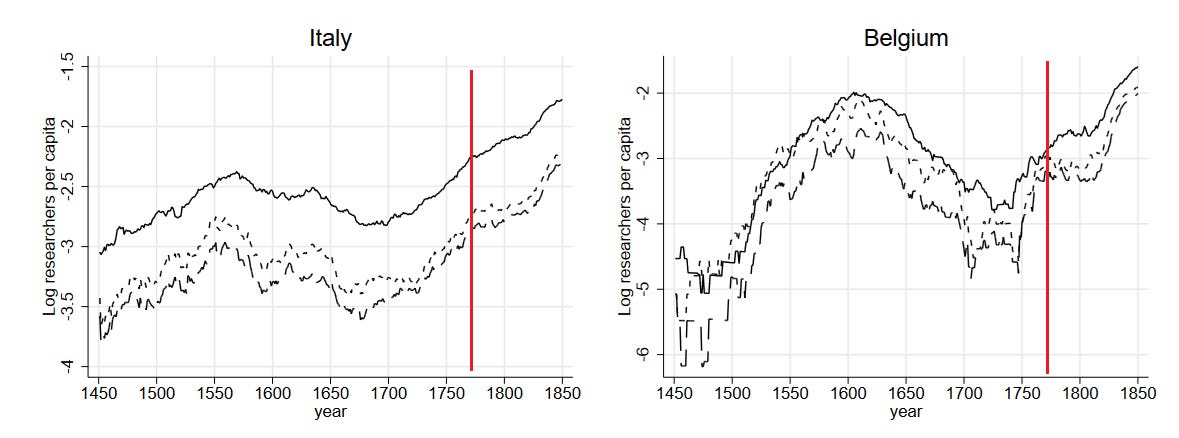

Looking at the rates in the previous chart, one might expect that Belgium and Italy also experienced a decline in scientific productivity following the expulsion of the Jesuits from their territories, though not as pronounced as that observed in Spain.

The expected decline is observable in Belgium, but absent for Italy, as shown in Cabello’s Figure D1:

Well, it’s not completely absent in Italy, where it looks more like a stagnation than a clear decline. The question then becomes: why was the impact of the expulsion of the Jesuits less significant in Italy compared to Belgium or Spain?

The southern half of Italy, ruled by the Spanish house of Bourbon, saw the expulsion of the Jesuits in 1767. Conversely, in Northern Italy, including the Papal States, the Society of Jesus faced suppression rather than expulsion, allowing many Jesuits to remain in Italy despite their order’s dissolution.

By 1768, most Jesuits expelled from Spain had taken refuge in Italy. Consequently, by the time Pope Clement XIV issued the final suppression of the order in 1773, theoretically applicable across all Catholic countries, Italy already hosted a significant number of Jesuits (more than before?) within its borders.

Although Jesuit colleges and seminaries were shut, northern Italy continued to benefit from the presence of the old educated Jesuits, many of whom found employment in libraries, universities or as private tutors.

While Spain and Portugal threw the baby (Jesuits)21 with the bathwater during their suppression, other Catholic countries wisely retained this highly educated group, thereby ensuring their sustained, albeit diminished, contribution to education.

The chaos of banishment, as witnessed in Portugal, was largely avoided; many Jesuits were allowed to remain and were even granted small pensions, but in terms of corporate existence, the blow [In France] was no less catastrophic22.

Tell me something I don’t know already

I've spent considerable time analyzing Cabello’s Appendix C23 up to this point, yet anyone with an adequate knowledge of the suppression of the Jesuits could have easily questioned Figure 8 (and not make such a fuss about a minor part of Cabello’s paper).

A key reason for my focus on the Jesuit suppression and its effect on Spanish scientific output is to underscore that scientific production is largely dependent on the institutions in which it (mostly) occurs, as well as the people who do the research and teaching, scholars and scientists.

Without the recruitment, selection, and training of potential scholars from among suitable students, any censorship or repression of existing scholars will merely be a secondary influence on total scientific output24.

The Reformation was, to a significant extent, a reaction to the ignorance, corruption, and greed prevalent among the clergy across much of Europe at that time. In response, a major initiative of the Counter-Reformation was the founding of colleges and seminaries, with the goal of combating clerical ignorance25 - as I’ve already mentioned, Jesuits soon distinguished themselves by their zeal in the founding of colleges and their erudition.

Thus, the Counter-Reformation took care of business, by making the priesthood less attractive as a business.

But in the process, it created a new problem. Religious orders, and secular clergy, now faced the necessity of selecting and recruiting individuals with the scholarly inclination to devote years to learning and training, thereby competing with other (secular) institutions for good candidates.

Assuming a limited pool of talented candidates, the Catholic Church was now recruiting some who might otherwise have pursued scientific careers in a secular setting. In the best case scenario, a scholarly inclined priest recruited by the Church could allocate some time to science, though only after fulfilling all clerical duties26. In the worst case scenario, a scholarly inclined priest might never find the time to do research.

The majority of Catholic priests engaged in science were less productive than they might have been under different circumstances. Likely less than the threshold of scientific production needed for inclusion in Wikipedia.

A high human capital perpetual motion machine

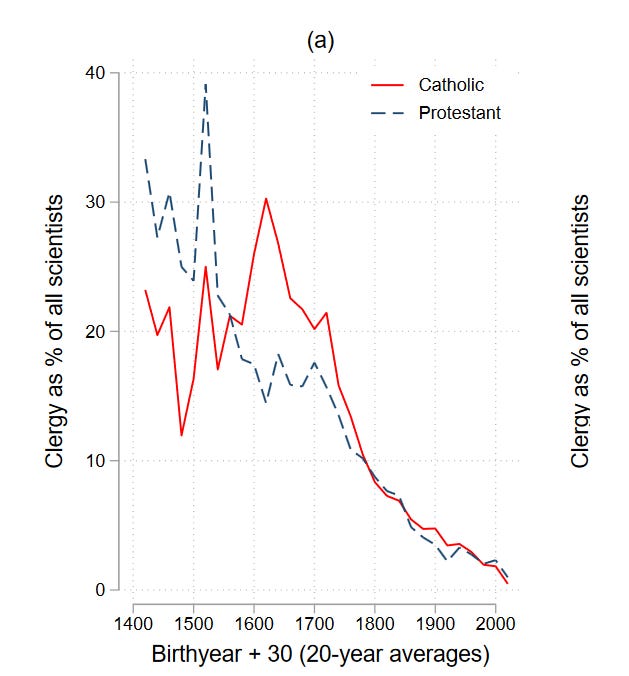

The Catholic Church effectively managed to capture a large part of the pool of potential scientists during the 17th and early 18th centuries. So large that the percentage of scientists who were also clergy was significantly higher in Catholic countries than in Protestant countries, as documented by Cabello (Figure D3):

Protestant countries also had clergymen scientists, though with less demanding schedules. However, the most remarkable difference between between Protestant and Catholic clergymen-scientists may lie in their recruiting procedures.

Before the Reformation, priests were often ignorant, corrupt, and greedy. Many were also non-celibate.

The Protestant solution to this issue was to do away with celibacy. The Catholic Counter-Reformation’s approach was to rigorously enforce celibacy.

This means that Protestant Churches could recruit from a candidate pool that was simply not available to the Catholic Church: children of clergy.

The fact that Protestant clergy had already been selected and recruited, proving their aptitude to assume clerical duties, does not guarantee that their offspring will be intellectually talented enough to become priests, let alone scientists. But it makes it much more likely relative to the children of laypeople.

My evidence for this is: I asked Grok to name six English scientists from the 18th century who were also part of the clergy. Out of the six it named, five were the children of clergymen27.

Now, let’s go back to that first chart presented by Cremieux, Figure 6a (Edict of Worms), comparing Catholic German cities to Protestant German cities. Why does the trend diverge between Catholic and Protestant German cities beginning around 1530-1540?

Considering the lack of evidence for the suppression of science during the early decades of the Reformation in Germany28, the most plausible cause is: the effects of different recruitment policies, which began to diverge in the early 1520s, started to become apparent around 1530-1540.

Catholic German cities underutilized their talent pool29 by recruiting candidates into the priesthood, while Protestant German cities freed these valuable human resources for deployment in scientific and other pursuits.

As to the second chart, Figure 6b (Isolationist laws of 1558-1559), I’ve already argued that the effects of the isolationist laws in Spain could not have had an immediate impact, as the chart implies.

Following the dissolution of the monasteries by King Henry VIII around 1540, it seems more likely that the British increase in scientists per capita, as opposed to Spain, from the 1560s onwards, is due to the new character of the English priesthood30.

It’s fun to be a French Cardinal

Now, let's return to the comparison between France and Spain - the fourth chart, Figure 6d, French Edict of toleration.

As I’ve mentioned before, the Counter-Reformation did not act in France through the French Inquisition, which was barely active. It also did not act through the Jesuits, who had barely any presence in France before 161031.

In fact, the Counter-Reformation appears to have made little headway during the 16th century in France, and only during the early 17th century began to make slow progress.

The founding of seminaries, aimed at ensuring the proper training of priests, was a major goal of the Counter-Reformation, yet the first seminary to be established in Paris - and indeed, the only one in the city during the 17th century - was founded in 1618 by the Society of the Oratory of Jesus32.

The Society of Priests of Saint-Sulpice, another society of priests in competion33 with the Jesuits and the Oratory of Jesus, only founded its first seminary in 1641.

Progress was very slow indeed, partly due to significant opposition from the French clergy towards Counter-Reformation ideas:

In 1644 Louis XIV… made [François-Étienne Caulet] Bishop of Pamiers. Caulet had not sought episcopal honours, but once a bishop he showed great zeal in the reformation of the clergy, the annual visitation of the diocese, the holding of synods, and the founding of schools, one of which was devoted especially to the training of teachers. The chapters of Foix and Pamiers, which he tried to reform, revolted openly

The rejection of the reforms by many ordinary French priests seems perfectly understandable when considering the behavior of certain top-ranking members of the French clergy was far from the ideals of austerity and integrity of the Counter-Reformation:

The personal fortune of [Cardinal] Mazarin at the time of his death [in 1661] was immense, amounting to 35 million livres, not counting the sums he left to his nieces. It exceeded the second-greatest personal fortune of the century, that of Richelieu, worth some 20 million livres. About one third of the personal fortune of Mazarin came from some twenty-one abbeys around France, each of which paid him an annual share of their revenue…Within the ebony cabinets of his rooms at the Louvre his heirs found 450 pearls of high quality, plus quantities of gold chains and crosses, and rings with precious stones, altogether adding another 400,000 livres. He left to his family jewels worth an estimated 2.5 million livres34

Cardinal Mazarin - who was never ordained as a priest - was the successor and protegé of Cardinal Richelieu, the chief minister of state of France from 1624 to 1642. Richelieu himself had also risen to the higher ranks of the French Catholic Church in a most French manner:

Henry III had rewarded Richelieu’s father for his participation in the Wars of Religion by granting his family the Bishopric of Luçon. The family appropriated most of the revenues of the bishopric for private use; they were, however, challenged by clergymen who desired the funds for ecclesiastical purposes…Thus, it became necessary that the younger Richelieu join the clergy.

In Richelieu’s defense, he made genuine attempts to enact the reforms advocated by the Council of Trent, despite the enduring French peculiarities that resisted the Counter-Reformation, such as the granting of an abbey to a priest not of its order, or even to a layperson, purely for financial gain:

The Council of Trent determined that vacant monasteries should be bestowed only on pious and virtuous regulars, and that the motherhouse of an order, and the abbeys and priories founded immediately from it, should no longer be granted in commendam…Especially in France, they continued to flourish to the detriment of the monasteries; for example Cluny Abbey. On the eve of the French Revolution of 1789, of the two-hundred-thirty-seven Cistercian institutions in France, only thirty-five were governed by regular Cistercian abbots.

Eventually, the Counter-Reformation did take hold in France. Enough seminaries were founded, and well-qualified priests were recruited to serve the French Catholic Church.

This transition to a regime of high human capital recruitment - akin to that established in other Catholic countries since the 16th century - corresponds to the inflection point in French scientific productivity illustrated in Cabello’s Figure 6d35. I’ve modified that figure to highlight this fact:

Conclusion

In summary, I agree with Cabello and Cremieux that the Counter-Reformation was the main cause of the scientific underperformance of Spain throughout the 17th, 18th, and even 19th century. However, I believe they are wrong about the primary mechanism behind this phenomenon.

Allow me to quote Cremiuex again:

Because, in the Malthusian era, knowledge was extremely fragile and small elite contractions could disrupt its transmission entirely

Whether the disruptions and inefficiencies that the Counter-Reformation introduced in the selection and recruitment of scientists can be described as “elite contractions” is debatable, but I’m pretty sure these changes adversely impacted the transmission of knowledge in Spain and other Catholic countries.

From Cabello: “In other words, a city that was at the same time Catholic, occupied by Spain, and the seat of a tribunal of the Inquisition is statistically associated with a sharper decline than is a city with just one or two of these characteristics.“

Cabello doesn’t mention the effects of human capital migration in his paper.

Cabello, 2023. Section 3: Biographical data.

Notice that Cabello is not completely consistent in the use of this metric. Figure 8 (Spain vs Belgium and Austria) uses scientists per capita aged 25 to 50.

Fall of Antwerp article in Wikipedia.

Seventeen Provinces article in Wikipedia.

“For one thing, they were depending on it, alongside the bishops, to help wipe out superstition and to advance the Enlightenment. They accordingly did no more than limit the powers of the Inquisition by, for example, in 1770 transferring cases of bigamy from its jurisdiction to that of the bishops”. “The Spanish inquisition: a history”, Joseph Pérez (2006).

“The Spanish inquisition: a history”, Joseph Pérez, page 42.

“The Spanish inquisition: a history”, Joseph Pérez, page 107.

Wikipedia article on Felipe Beltrán (or Bertrán).

“The Spanish inquisition: a history”, Joseph Pérez, page 94, footnote 23.

Aspectos sobre la elaboración del Indice Inquisitorial de 1790, Dionisio A. Perona Tomás.

I’ll go back to the Jesuits in a moment.

Aspectos sobre la elaboración del Indice Inquisitorial de 1790, Dionisio A. Perona Tomás.

Juan Antonio Llorente, Holy Office commissioner in the Logroño Inquisitorial court, opined that “the censorship of books that the inquisitors exercised was stupid: not only did it contribute to sullying Spain’s prestige abroad, but it furthermore maintained ‘a slavery of the mind, to the great detriment of humanity’“. Quoted by Joseph Pérez, “The Spanish inquisition: a history”.

Defourneaux, M. cited by Dionisio A. Perona Tomás.

“The Counter-Reformation revived: some case studies, 1700–1990“

Notice that the small uptick beginning around 1800, following a period of recovery for Spanish education post-1767, reverses again at the start of the Peninsular War (1808-1813).

Cremieux links to another very interesting article of his, exploring this subject.

Even today, Spain has a low population density compared to much of Europe.

Yes, that was a pun.

“From Immolation to Restoration: The Jesuits, 1773–1814“, Jonathan Wright, 2014.

“The Counter-Reformation revived: some case studies, 1700–1990“

Scholars and scientists are not only necessary for advancing scientific knowledge but also to preserve what has already been achieved.

But also combating corruption/nepotism. Who wants to buy a bishopric if it requires several years of study. That’s very low ROI.

Biographies of scientist-clerics suggest that a few exceptionally talented priests were able to devote most of their time and efforts to scientific endeavors, yet they appear to be the exception rather than the rule.

John Michell, William Buckland, Thomas Bayes, William Whiston, Stephen Hales (NO), John Flamsteed.

I’m open to any evidence that might be presented.

From a scientific rather than a religious perspective.

It’s worth noting that England experienced a period of Catholic suppression under Edward VI's rule (1547-1553) and Protestant suppression during Mary I's reign (1553-1558), yet these don’t appear to have had an impact on English scientific productivity.

The Jesuits were expelled from France in 1594 and not permitted to return until 1603. The order was not very powerful or influential in France before 1594. Prior to their expulsion, the order had limited power and influence in France.

The Society of the Oratory of Jesus is a society of apostolic life, not an order.

All three religious institutions- only the Jesuits being a religious order - focused their efforts in the field of education.

It also coincides with the emigration of hundreds of thousands of Huguenots from France who, just like their Southern Dutch Protestant coreligionists in the late 16th century, disproportionately came from a bourgeois background.

Great stuff. I'm really intrigued about whether this is comparable to the similar shift of intellectual people towards the clergy in Islamic countries in the early 1st millennium, with even more dire consequences.