Colombian elections (looking for structure in Venezuela's political culture?)

Exploring some shared cultural traits between neighbors Colombia and Venezuela.

As I mentioned in a previous post, during the Spanish colonization of the Americas, large numbers of Canary Islanders migrated to the Caribbean region, especially settling in the larger Antilles (Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico) and along the tropical coasts.

Also, in my last post about Venezuelan regional diversity and its relation to historical voting patterns in the country, I noted that Venezuela has a temperate mountainous region in its southwest, bordering Colombia. In terms of climate and geography, this temperate region can be seen as an extension of Colombia’s Andean region:

The climate and vegetation of the region vary considerably according to altitude, but as a general rule the land can be divided into the tierra caliente (hot land) of river valleys and basins below 1,000 m; the more temperate conditions of the tierra templada (temperate land, approximately 1,000 m to 2,000 m) and tierra fría (cold land, 2,000 m to 3,200 m), which include the most productive land and most of the population;

Similar to Venezuela, early Spanish settlers in Colombia preferred the temperate regions over the low-lying coastal areas and valleys, not only because of the more agreeable weather, but also due to the presence of gold1 in the mountains.

In the 17th-century, Canarians started settling the Caribbean coast of northern Colombia in significant numbers, encouraged by the Spanish government which feared that the sparsely populated region would be a tempting target for foreign actors, including pirates.

These immigrants eventually imbued the Colombian Caribbean coast with a distinct Canarian character, similar to that found in other Caribbean regions. Even now, the local Spanish dialect, Costeño, more closely resembles other varieties of Caribbean Spanish than it does the Spanish spoken in the Andean interior of Colombia (Paisa, Cundiboyacense, etc).

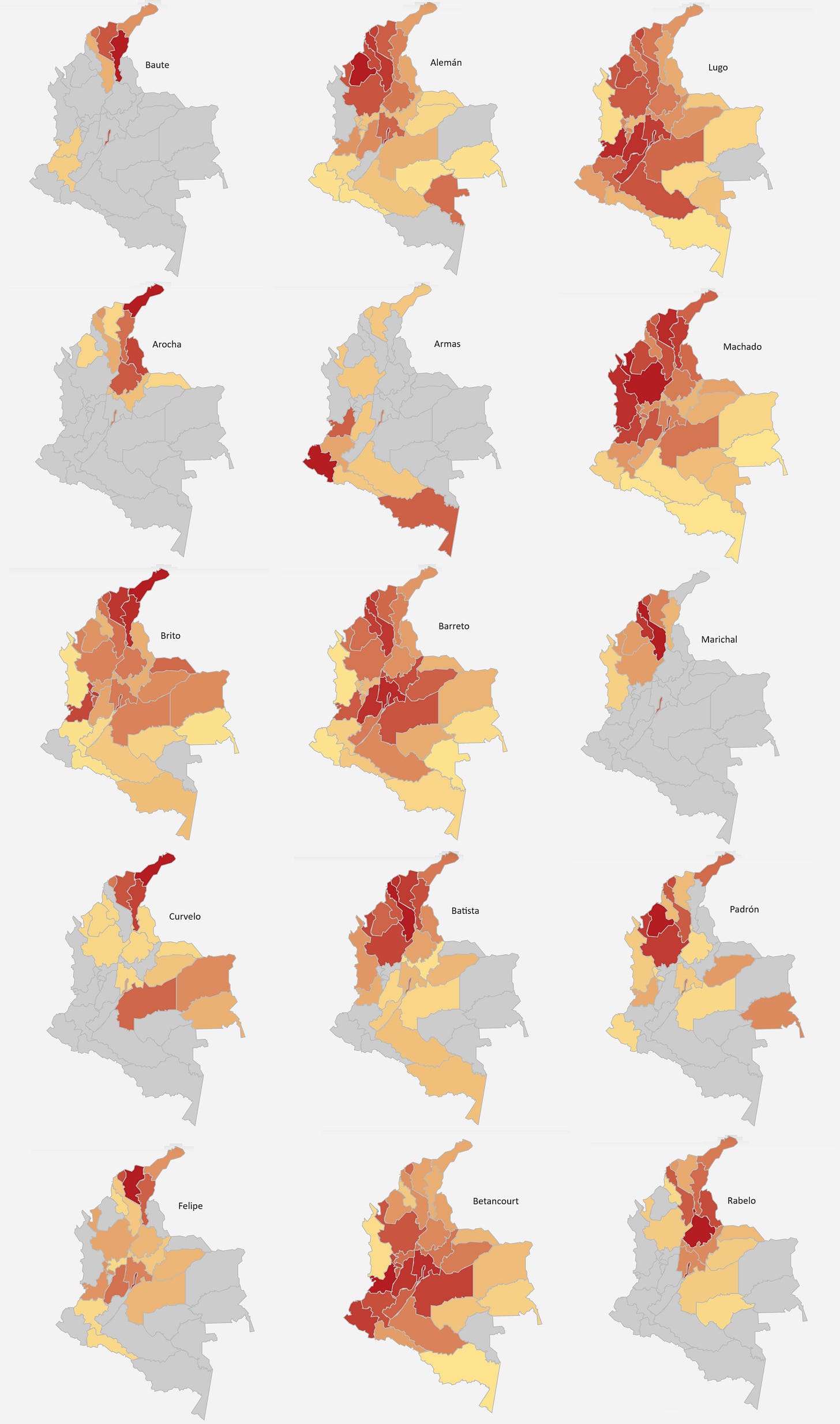

Just like I did for Venezuela2, I’ve procured maps of the geographical distribution of Canarian surnames in Colombia, showing the relative concentration of those surnames in the Caribbean coast, reflecting the settlement pattern I just mentioned:

Unlike in Venezuela, the geographic confinement of Canarian descendants to Colombia's Caribbean region is less pronounced, but it is clear enough to suggest that cultural differences between the Caribbean coast and the interior could be attributed to differences in ancestry.3

Colombian electoral maps

Before I present any Colombian electoral map, allow me to quote from my previous post on Venezuela:

Throughout this period - particularly before the 1980s - [Venezuelan] Andinos predominantly voted for the Copei party, a Christian democratic party commonly regarded as the right-wing half of the two-party system during the Puntofijo era. It’s main rival was the Democratic Action (AD) party, which could be considered the left-wing party.

So, does my hypothesis that Venezuelan regional voting patterns, and other cultural differences, derive from the cultural differences between Canarian settlers (a major component of the colonization of the Caribbean coast) and those from other Spanish regions hold up when applied to the case of Colombia?

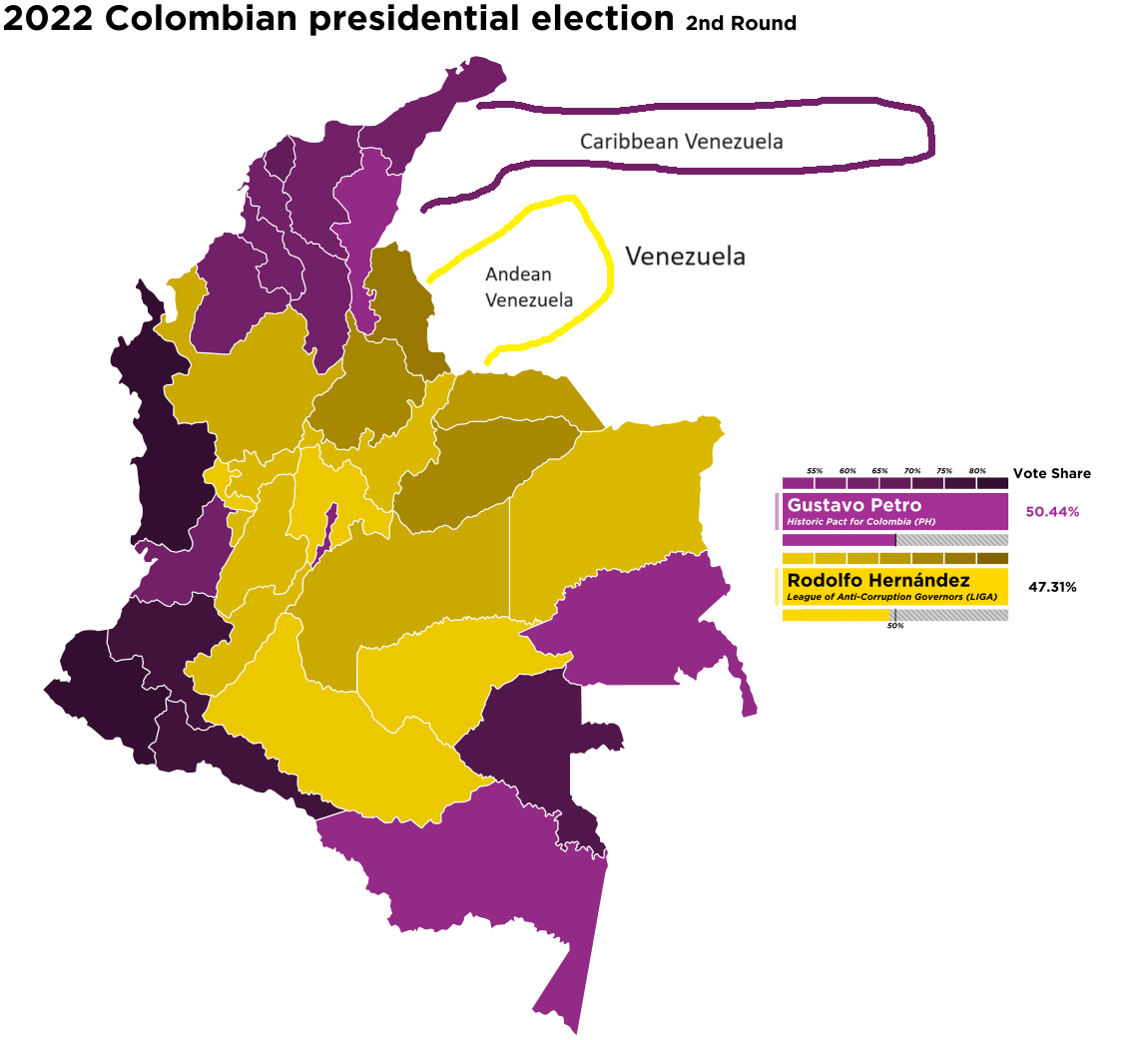

Let's look at a map of the last Colombian presidential election results and see if we can answer that question:

The purple-colored areas on the map represent the Colombian states where the majority voted for the left-wing candidate, Gustavo Petro, whereas the yellow-colored states are those that supported the right-wing candidate, Rodolfo Hernández.

I modified the original map by adding a purple circled area to denote Caribbean Venezuela, which is adjacent to Colombia’s Caribbean coast, and a yellow circled area to represent Andean Venezuela, right next to Colombia’s Andean region.

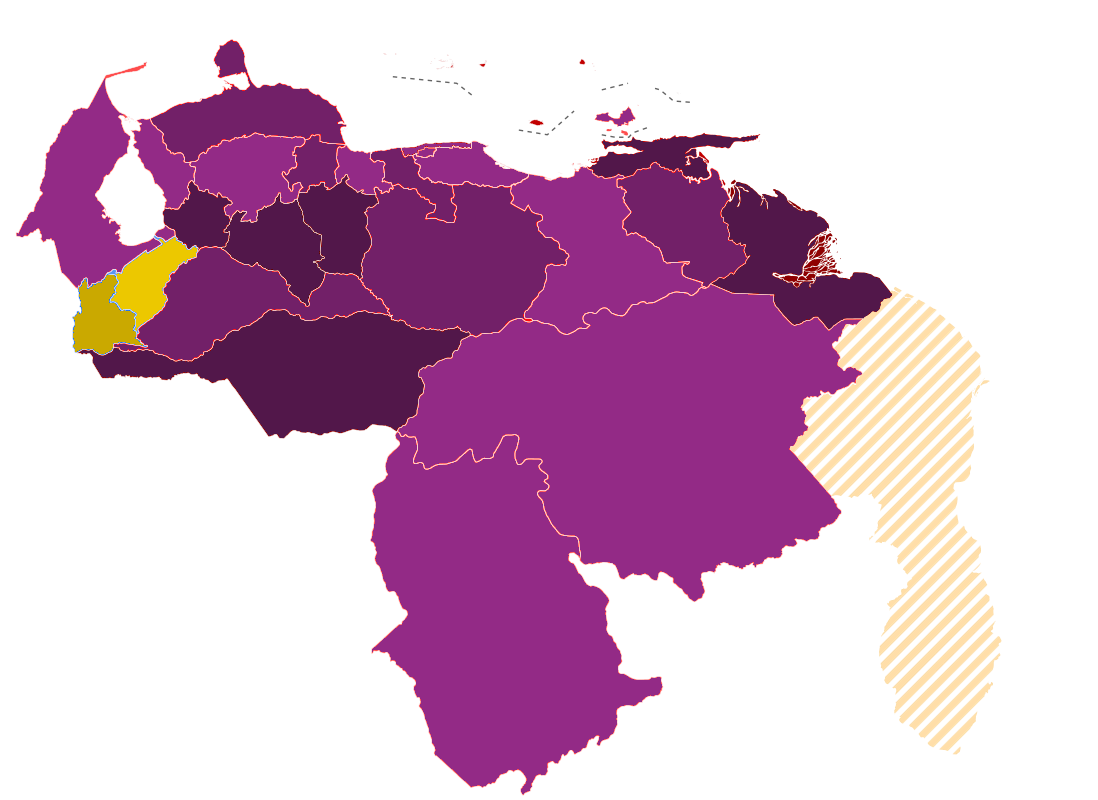

You will notice that, as is typically the case in Venezuela, the Andean regions leaned towards the right, while the Caribbean regions favored the left, as you can see in the following map of Venezuela:

Similar to our approach in the Venezuelan case, we should ask whether this is a persistent pattern or a recent occurrence.

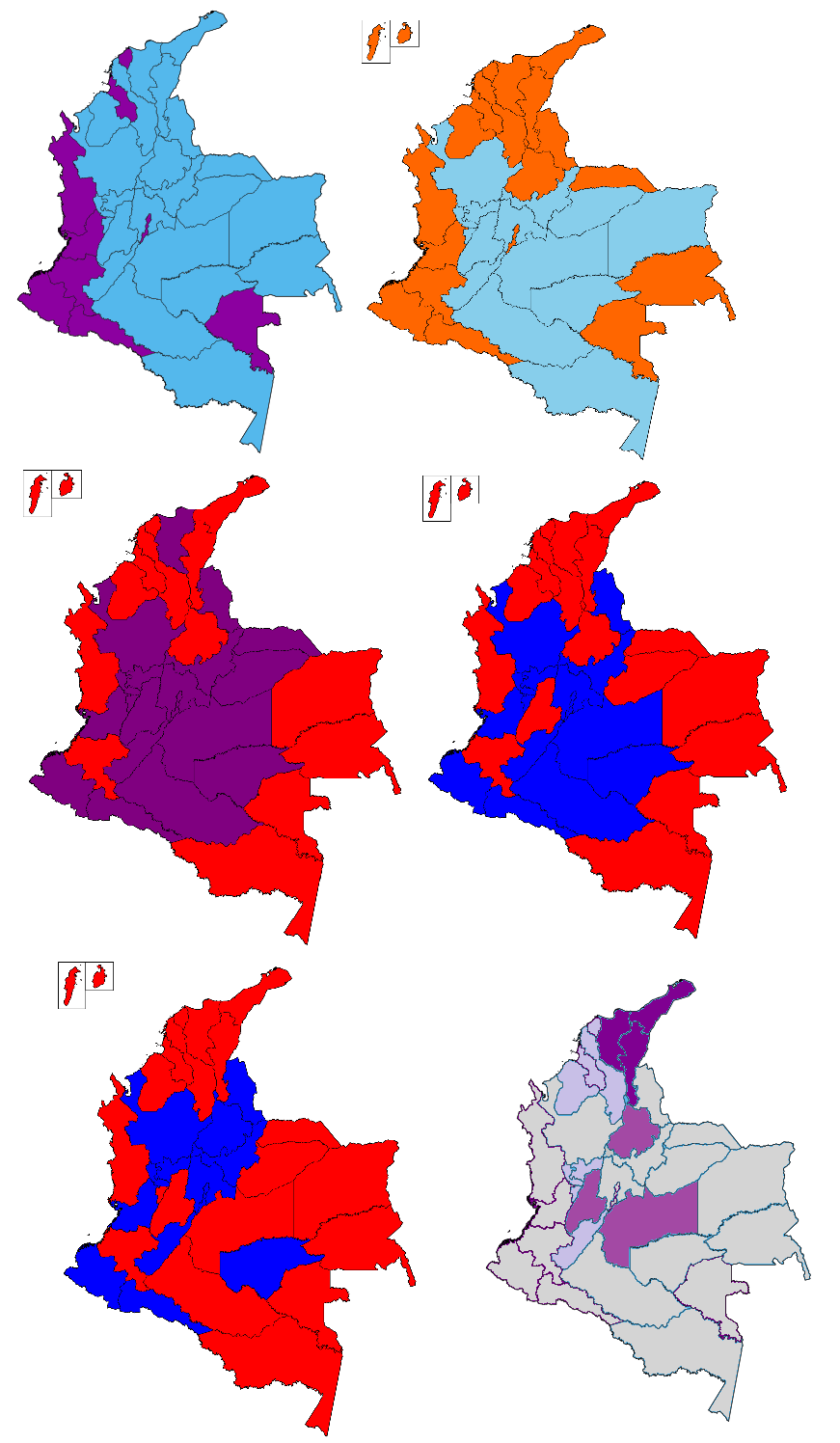

And to address that question, I have compiled a series of results maps of Colombian presidential elections from 1962 to 2018:4

According to those maps, Colombia mirrors Venezuela in that its Caribbean and Andean regions exhibit distinct voting patterns.

Historically, in most Colombian elections, the Caribbean region has shown a stronger preference for the left-wing candidate (typically the Liberal party candidate) than the Andean region, mirroring the electoral trends for Venezuela.

Notice that in recent elections, additional patterns seem to have emerged, with the easternmost states and those along the Pacific coast states also favoring left-wing candidates.

What about other explanations?

Of course, other explanations for the regional voting patterns of Colombia and Venezuela, not rooted in cultural traits, are plausible. The consistency of the cultural hypothesis across both sides of the border does not necessarily mean it is right.

Let’s examine the economic hypothesis. By this, I refer to the notion that poorer communities and regions tend to vote left while more affluent communities and regions tend to favor right-wing parties.

Let's begin with Venezuela. Since I couldn’t find historical (20th century) GDP per capita data for each Venezuelan state, I will instead quote from my previous post:

The western pink circle encompasses the oil-producing region of Zulia, while the eastern pink circle is the oil-producing region of Anzoátegui. Together with the state of Monagas, located immediately east of Anzoátegui, these regions account for over 90% of Venezuela's oil production.

The green circle surrounds the mineral-rich region centered in Ciudad Guayana, Bolívar state. This area was responsible for some of Venezuela's main exports beyond oil, including iron, steel, and aluminum, in large part thanks to the plentiful energy produced by the nearby Guri Dam, which is the sixth-largest hydroelectric dam in the world.

These regions, in contrast to the Andean region, are very rich in natural resources.

Given their scarcity of natural resources, it is highly unlikely that the Venezuelan Andean states were richer than the national average during the second half of the 20th century5. Are they wealthier now, in 2024?

Based on their GDP per capita and Human Development Index (HDI), the answer is clearly no:

Notice that, in addition to the Andean states (highlighted in red), I have also highlighted Barinas state in blue, which is located just to the southeast of the Andean states. Barinas also seems to lean more right, especially in the municipalities right next to Táchira and Mérida, and yet it is the second poorest state in Venezuela.

Now, let’s examine whether the economic hypothesis holds true for Colombia.

Here are the GDP per capita numbers for all Colombian departments. In this instance, it’s the Caribbean departments, not the Andean ones, that I have highlighted.

In the Colombian case, I cannot entirely dismiss the economic hypothesis as I did for Venezuela. Approximately half of the Caribbean departments have a GDP per capita near the national average, while the other half clearly fall into the lower range. But this doesn’t prove the economic hypothesis either. Seven out of the 10 poorest departments voted for the left in the 2022 presidential election, but most of the wealthier departments that also voted for the left were located in the Caribbean region.

The differences in political culture between Caribbean/Canarian Venezuelans and Andean Venezuelans are not merely superficial or the product of recent developments, but stem from deep historical differences related to the diverse settlement patterns that shaped different regions of the Spanish Americas.

Specifically, Canarian settlement occurred not only in the Caribbean region of Venezuela, which is the main region of that country, but also along the Caribbean coast of Colombia, which is a minor area of Colombia.

This settlement, which I previously called Canari America, brought with it the seeds of Venezuela’s political culture.

I had to replace six of the original fifteen surnames, as their frequency was too low. I’ve used the following surnames as replacements: Arocha, Brito, Curvelo, Felipe, Padrón, Rabelo. You’ll notice that three surnames don’t follow the expected geographic pattern, and one surname only partially follows the expected pattern.

There’s also genetic evidence of Canarian ancestry in the Caribbean coast. One study found that 3.3% of all West Eurasian paternal lineages in Bolívar state are E1b1b-M81. Given that 8.3% of paternal lineages in the Canaries are E1b1b-M81, this suggests that approximately 40% of all male European ancestors of Caribbean Colombians were Canary Islanders. In contrast, another study appears to suggest that Canarian paternal ancestry is low among Colombians in the interior city of Medellín.

The 1962 presidential election map is my own work, based on data from Wikipedia. Light purple color is > 20% for López Michelsen (Liberal candidate); purple is > 30%; dark purple > 40%.

During the later part of the 19th century and the early 20th century, the Andean region of Venezuela was a major producer of coffee. At that it was probably wealthier than the rest of the country.