On Uruguayan religious culture

Is Uruguay somewhat Caribbean?

It’s time to revisit an old post, from November 2024, titled Canarian religious culture in the Americas, where I wrote:

It also reveals the Caribbean region as particularly irreligious within Latin America. For Latin America as a whole there are 5,159 Catholics per priest, whereas the four Hispanic Caribbean nations average a much higher CPP ratio of 8,324.

The previous chart, contrasting the four Hispanic Caribbean countries that form the core of Canari America with other similarly Hispanic countries, makes the lower religiosity of this region of Latin America conspicuously evident.

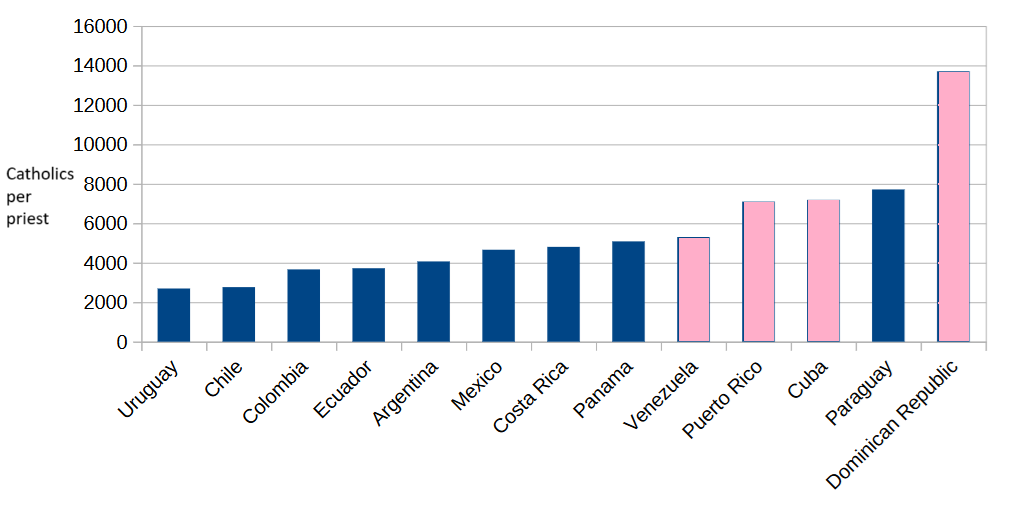

The chart I was referring to, showing the number of Catholics per priest in the year 1950 across 13 Latin American countries is this one:

And if you contrast that chart, where Uruguay appears to have the highest religiosity in Latin America, with my latest post, The Canari American marriage pattern, where I wrote: “I feel compelled to highlight aspects of Uruguayan culture that may show Canarian influence… Uruguay’s cohabitation ratio is almost triple that of most neighboring subnational entities“, it may seem like there’s a contradiction between the two posts, or at least there’s a valid yet overlooked piece of evidence challenging the notion that Uruguay is very Canarian.

To refresh your memory, the Catholics Per Priest ratio (CPP) is calculated by dividing the Catholic population of a diocese by its number of priests, and my interpretation of this ratio is that the higher a country’s CPP is, the lower its religiosity. And in the same November post, I showed that the Canary Islands had the highest CPP ratio among Spanish regions, and presumably the lowest religiosity, in 1950.

That’s why it seems contradictory that I would attribute the high CPP ratio and low religiosity of countries like Cuba and Venezuela to Canarian influence, while Uruguay, a nation which also received a large number of Canarian immigrants, has the lowest CPP ratio among all 13 countries.

A plausible explanation might be that although Uruguay welcomed a large number of Canarian settlers, the influx was not as substantial as that received by Cuba and Venezuela. Based on my admittedly rough estimation of Canarian descendants in the new world, around 40% to 45% of European ancestry in Cuba and Venezuela stems from the Canary Islands, while only 30% of European ancestry in Uruguay originates in the archipelago1. So, if Uruguay is less Canarian, it should be less culturally Canarian.

Yet, it’s somewhat inconvenient for my thesis that Uruguay not only appears more religious than Cuba and Venezuela, as shown by its low CPP value, but seems to be the most religious country in all of Latin America.

The exception to the rule?

I must admit my main focus of interest when I started researching the religiosity of Latin American countries was Cuba. The reason I chose the year 1950 for my initial research was simply to avoid the effects of the 1959 Cuban Revolution on the CPP ratio and on Cuban religiosity itself2.

It should come as no surprise that the number of priests in modern-day Cuba is rather small, and the country’s CPP is very high, after more than six decades of official atheism and religious repression3. It would be absurd to ascribe Cuban low religiosity to Canarian cultural influence. If we want to measure religiosity in Latin America in the 21st century, Cuba’s CPP is not going to be very informative, so we might as well ignore it. But setting aside Cuba’s data, looking at more recent Latin American CPP values can still be informative, and that is exactly what I did.

But before we take a look at recent CPP data, specifically from the year 2020, there are two issues I want to address.

First, I’m not using the exact 2020 CPP values calculated by catholic-hierarchy.org. Since my goal is to gauge the religiosity of the general population, if only 50% of the population of a traditionally Catholic country identifies as Catholic in 2020, I want to preserve the information this percentage provides. To give an example, if a population of 4,000 includes only 50% who declare themselves Catholics and two priests serve that population, catholic-hierarchy.org reports a CPP of 1,000 (2,000 divided by 2), while I will calculate a CPP of 2,000, implying substantially less religiosity4. This wasn’t an issue when dealing with 1950 CPP data, as nearly all Latin American countries were close to 100% Catholic at the time.

Second, regarding the 13 “other similarly Hispanic” countries I mentioned, the justification for restricting the previous analysis to them was:

To assess the specific impact of Canarian heritage on Latin American religious culture

, as opposed to other regional Spanish heritages (like Andalusian, Basque, Castilian, etc.)in the former Spanish colonies, I will exclude from this analysis the aforementioned countries where overall Spanish ancestry - from any region of the mother country - is not predominant.

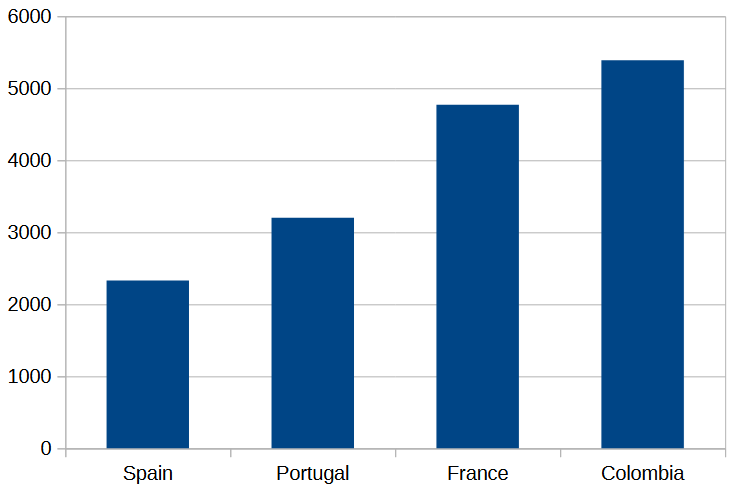

In 2020, just like in 1950, the excluded countries5, characterized by higher Indigenous American ancestry, exhibit higher CPP values. This aligns with the observation that European Catholic nations remain more religious than Latin American countries, which are only partially European, in 2020.

I’m keeping the same criteria, thus including the same 13 countries in this analysis (plus Brazil).

And now, without further ado, let’s see if we can find anything interesting in the 2020 Catholics Per Priest data for Latin American, whether related to Uruguay or otherwise.

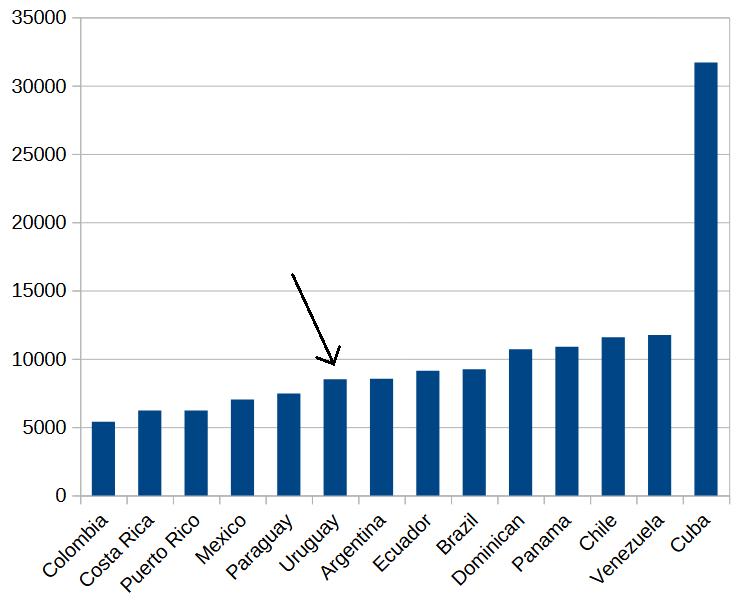

Well, from 1950 to 2020 Uruguay has moved from exceptionally high to fairly average religiosity. Other changes in the rank of religiousness surprised me (see Chile6 and Paraguay7), but I can’t say that Uruguay’s shift did.

This is still a bit disappointing from my point of view, because Uruguay doesn’t have a high CPP ratio even when compared to its neighbors Argentina and Brazil. But I’m a stubborn man, so I decided to keep digging and delve into the regional 2020 data for Argentina and Brazil.

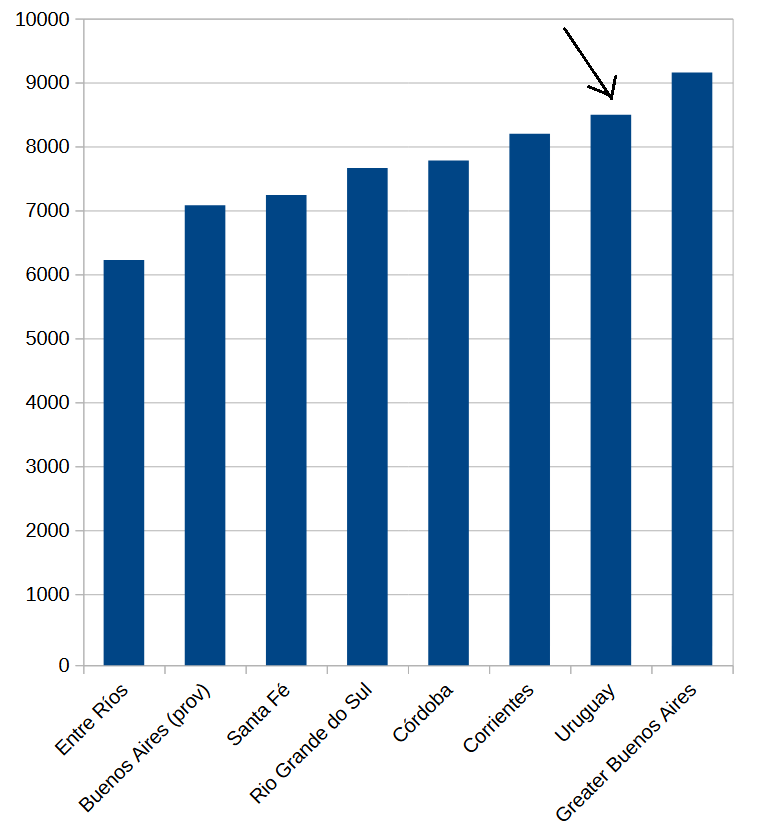

The bar chart I’m now going to show you displays the CPP values for seven Argentine provinces and Brazilian states bordering or near8 Uruguay. These subnational entities are mostly comparable to Uruguay in size and population, and just like Uruguay, they received a substantial number of European migrants during the late 19th and early 20th century. You could say they are nearly as European as Uruguay, but without a significant Canarian influence.

Turns out that compared to similarly European regions of Argentina and Brazil, Uruguay actually looks less religious. It’s Catholics per priest ratio is unusually high.

So, there you have it. The 2020 CPP data doesn’t conclusively prove that Uruguay is a low religiosity country, but it does imply an unexpectedly lower religiosity than what 1950 data suggested. Uruguay may not be the most culturally Canarian country in Latin America, but it’s far from being the least.

The Annuario Pontificio, the Catholic Church yearbook used as a source for the website that provides my CPP data, does not offer information for every year. The next year after 1951 with complete CPP data is 1967, several years after the Cuban Revolution took place.

Though Cuba’ government has recently relaxed restrictions, recognized religious freedom and generally made religious practice less difficult.

If I had applied the same criteria to 1950 data, Uruguay would not have the lowest CPP but second lowest, after Chile.

These are: Bolivia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua and Peru.

Chile’s transition from one of the most religious countries in 1950 to the third least religious in 2020 is linked to a sudden decline in the number of religious priests within the diocese of Santiago. In 2017 there were 517 religious priests in the diocese, then the number drops to 250 in 2020, and finally rises to 396 priests in 2023. I don’t know if this is an error in the data, but it looks very suspicious to me.

By 1966, Paraguay’s CPP was already much lower than in 1950, recording approximately 5,168 Catholics per priest.