Nitpicking the mimetic mixing theory of Israeli fertility

Maybe the Israeli social mixer is not such a good mixer?

The thing about spending time working with a dataset is the more you work with it, the easier it becomes to extract information from that data. This is precisely what has happened to me in the last couple of weeks with regards to Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) data.

When most people think about the topics Fertility and Israel, they most likely do not think of the fertility of Arab Israeli citizens, but of Jewish Israeli fertility, and so my two last posts discussing Arab Israeli fertility and religiosity might have come as a surprise, or even a disappointment.

However, not only do I think those articles are cool1 and a small contribution to the discussion of the “religious hypothesis”, I also learned a lot about working with CBS data. And now I want to use what I’ve learned to write about the actual thing most people have in mind when Fertility and Israel come up for discussion.

While nearly every developed country has seen its birth rate fall below replacement level in the last few decades, Israel stands out as an exception to the rule, with a Total Fertility Rate (TFR) of around three children per woman. This remarkable fertility rate has prompted numerous theories trying to explain why Israelis, and Jewish Israelis in particular, have so many children.

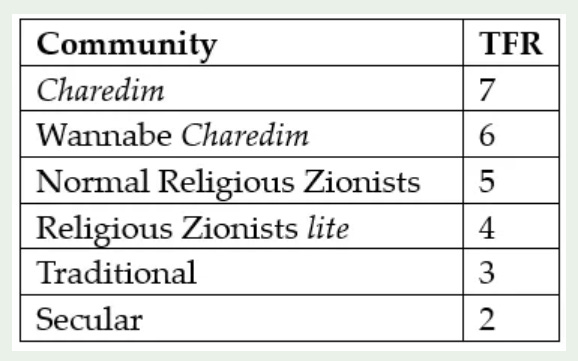

Part of the puzzle can be easily explained by the very high fertility rates of Israel’s most religious communities. Haredi Jews (like the family in the image above) are the most religious and have the most children - approximately 6.5 children per woman; then come Dati, the Religious/Very Religious (in CBS’s classification), with roughly 4 children per woman; and finally the two least religious groups, Traditional and Secular Israelis, with birth rates below 3.

While the high fertility of the two most religious groups mirrors the high birth rates seen in other highly religious communities, the Traditional and especially Secular groups defy the trend towards lower birth rates that we see in the (mostly secular) rest of the developed world, with Secular Israelis maintaining a TFR of around 2.0 children per woman - close to the replacement level.

This Secular birth rate is exceptional when compared to those of the United States (1.62), the UK (1.54), Germany (1.46), Japan (1.23) or Poland (1.31)2, and therefore it’s no wonder that explanatory theories have focused on the Secular group. What are some of these explanatory theories?

Repeated existential threats foster a cultural norm of high fertility.

Pro-natalist government policies. These include everything from subsidized In vitro fertilization (IVF) to affordable childcare.

Strong family culture.

Those seem to be the most commonly cited ones. And I want to focus on the third, strong family culture, which was very widely discussed online following the publication of this article some time ago3:

My goal here is not to discuss NonZionism’s article in detail4. But when I started digging into the CSB data - particularly the kind of data that could support or contradict the cultural explanation - his post immediately came to mind. In NonZionism’s words, this is how strong family culture works in Israel:

What these groups do is provide a one-way channel of influence between Israeli Charedim and the rest of Charedi society, a sort of valve in which Charedi fertility memes can spread outwards, without allowing fertility decreasing memes inwards.

With a lot of mixing and mingling (emphasis mine):

Around 25% of the Religious Zionist [Dati] community is actually barely religious at all and very comfortable freely mixing with ‘traditional’ Israelis who don’t keep the Sabbath, but ‘respect’ it…Finally, these traditional Jews mingle with secular Jews, who pick up the last scraps of the Charedi fertility meme, enough to keep their demographic head above water.

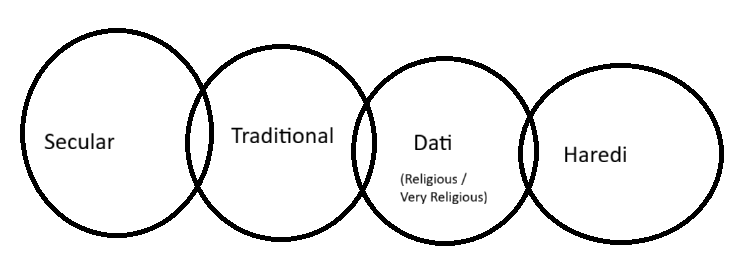

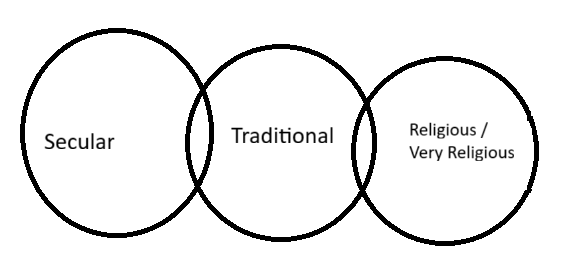

The basic model here is that, unlike anywhere else in the world, there is no hard cultural barrier (at least in one direction) between Charedim and the rest of society, and enough mimetic stepping stones that almost everyone is influenced to some degree. A very simplified model looks like this:

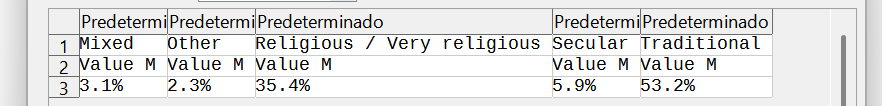

The mixing of religious groups that NonZionism describes is what I want to test with the CBS data. Remember we have data on the share of households in each religiosity group (Haredi, Dati, Traditional, Secular) for every Israeli city with a population above 10,000 and we’ve analyzed these data before. It looks like this:

You can see in the screenshot above that the CBS also reports the share of Mixed households and Other households in each city. Mixed is the one I’m interested in, because, as its name implies, it directly measures the mixing of Jewish religious groups in a very consequential setting: living together as a household.

Before we continue, a caveat. To simplify calculations, throughout this post I assume that mixing occurs between “contiguous” groups (e.g. Traditional and Dati) rather than between non-contiguous groups (e.g. Traditional and Haredi) because the likelihood of the former household setting is far higher than that of the latter.

Digging into the data

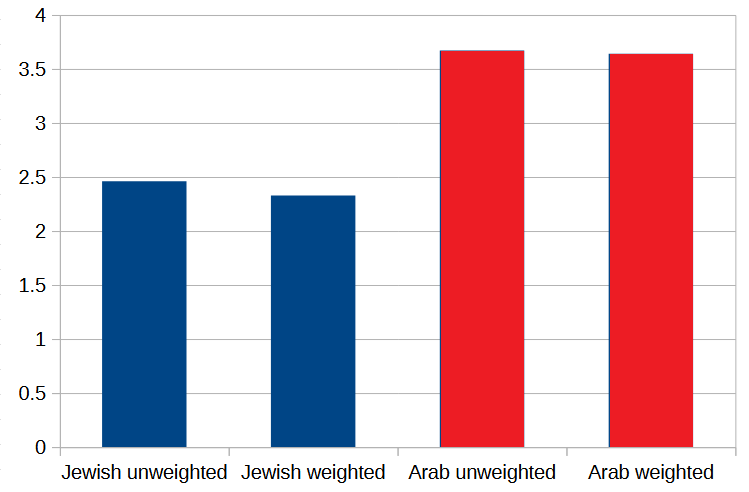

Let’s start with the raw average share of Mixed households. The average value across 86 Israeli cities is 2.46%; it drops slightly to 2.33% if we weight cities by their population. Is that high or low? Unless we have another mixed households value to compare it to (maybe from another country?), it’s hard to tell whether Jewish Israeli society has few or many Mixed households.

Well, we don’t have a comparable figure from another country, but we do have the closest thing to it: the percentage of Mixed households in Arab Israeli cities. As I’ve mentioned before, apart from a few exceptions, Jewish and Arab Israelis do not generally live in the same cities. Thus, the Mixed households percentage of an Arab city exclusively reflects the degree of mixing within Arab Israeli society.

And here’s a first (naive) comparison of the Jewish Israeli percentage to the Arab one:

At first sight Jewish Israelis are substantially less prone to mixing than Arabs (3.67% unweighted).

But, are we sure that we are comparing the same thing?

Mixing always involves exactly two groups5, so in the case of Jewish Israelis the four religiosity levels yield three possible mixed household settings. But there is no Arab equivalent to the Ultra-Orthodox/Haredi community in the CBS data. There are only three Arab Israeli religious groups and consequently only two possible mixed household settings6.

This difference in the number of possible mixed settings for Arabs and Jews implies that if both were equally prone to form mixed households, Arabs cities would show roughly 16% more Mixed households than Jewish ones - if this sounds counterintuitive, please read this footnote7.

That still leaves a large gap unexplained. Arab Mixed households are 50% more common than Jewish ones, not 16%. Jewish Israelis still seem significantly less inclined to mix across religiosity boundaries than Arabs.

Plotting the mixing

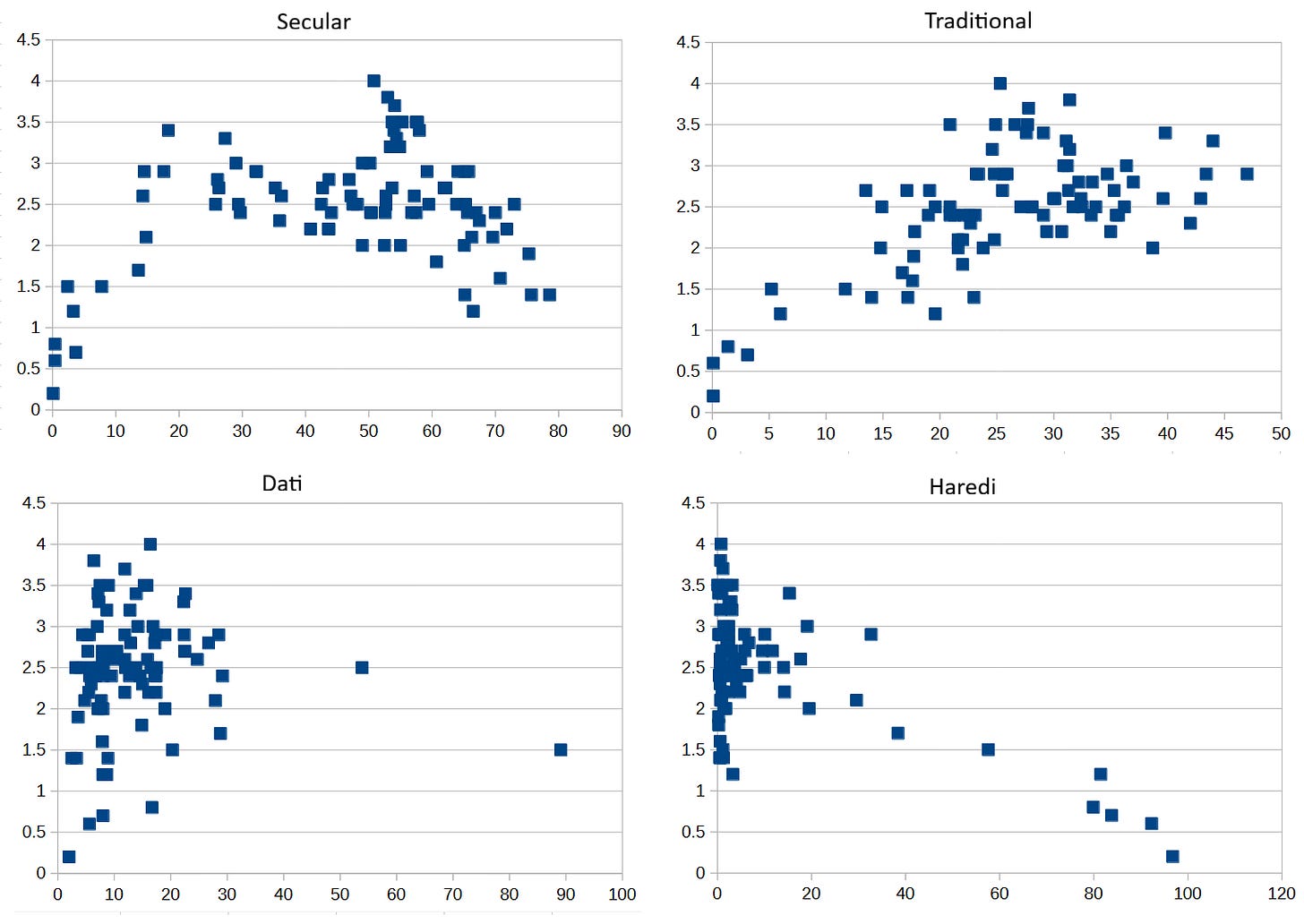

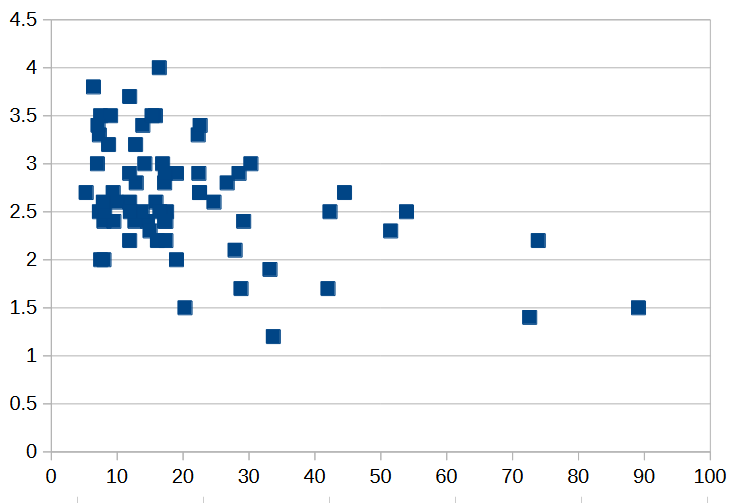

While trying to figure out if there’s any more information that can be extracted from the data on religiosity, I decided to take a look at the scatter plots of Mixed household share vs the share of each religiosity group. And at first glance, they look completely random8.

The only thing that caught my attention are the six obvious outliers far from the shapeless main cloud of data points. Five of those six outliers are Bedouin cities - Israeli Bedouins are really weird. I then recreated the two scatter plots excluding Bedouin cities, but I’ll save you the effort of looking for any pattern in those plots: there is none.

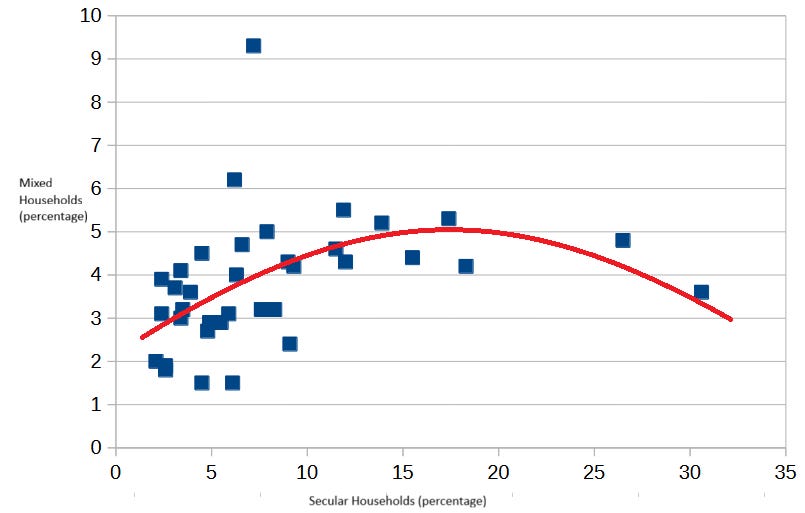

Where I did see some kind-of sort-of pattern emerge is in the scatter plot of Arab Mixed household share vs Secular household share, after excluding Bedouin cities.

The pattern I highlighted in the plot may not be real (really; just two points in the right half of the plotted area and somehow there’s supposed to be a downward curve there), but it persuaded me to create the same scatter plots for the four Jewish Israeli religiosity levels.

The Mixed vs Traditional and Mixed vs Secular plots seem to reveal an inverted-U curve - though in the case of Mixed vs Traditional only the left half of the curve is visible for lack of data points (cities with more than 50% Traditional households). To understand why this is expected, consider a city where the population of one religiosity group, say Secular, is close to zero; assuming that Secular individuals have a constant propensity to mix (P), independent of group size, the number of Mixed households including a Secular individual will necessarily approach zero9.

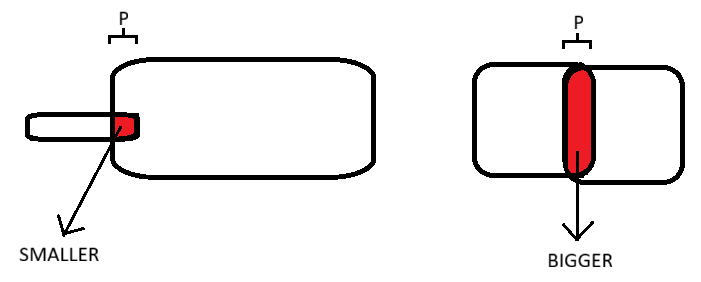

At the other end of the scale, if the Secular share of population approaches 100%, the number of individuals in other religiosity groups will be very few, and the number of those prone to mixing will be even fewer. In graphic terms:

So, when the share of religiosity group X (Secular, Traditional, Dati or Haredi) approaches 0% or 100%, the percentage of Mixed households will tend to be lower than when the share of X is farther from the extremes.

But wait. The Dati and Haredi scatter plots don’t look like an inverted-U curve10. And both plots include data points near the 100% mark, so the explanation can’t be that we are missing the right half of the curve, as happened in the Traditional households plot. To be fair, if I squint enough, I can see a curve in the Dati plot, though the right half is made up of just two points. Yet the Haredi plot (lower right) does not look like a curve, no matter how much I squint. In fact, if not for the widely dispersed data points in the extreme left (with near 0% Haredi share), the plot would look like a downward straight line.

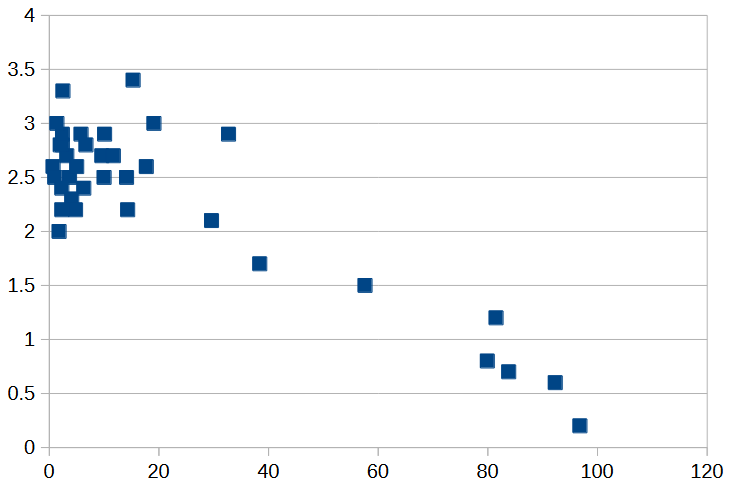

Most cities represented by those scattered points on the left have a relatively balanced distribution of Secular, Traditional and Dati households, tough a few are overwhelmingly Secular or overwhelmingly Dati cities. And since I’m very uncertain about the effects of a high (but not near 100%) Secular or Dati share, I decided to exclude from the plot all cities with more than 50% Secular or 50% Dati households.

That looks like a very convincing downward straight line to me11. The more Haredi population in a city, the less mixing there is. And the fewer Haredi households, the more mixing takes place in that city. That sounds like the opposite of what I would expect if other religiosity groups looked up to Haredis and drew inspiration from them.

If low rates of mixed households imply little interaction, I can’t see how Haredis are supposed to influence the broader Israeli population. There’s no reason to think they exert influence through economic status - they are the poorest community among Jewish Israelis. They lack military prestige (big in Israeli society12) that could raise their status - Haredis are the only group which does not serve in the Israeli armed forces. And they dedicate their lives to an endeavor that has close to zero appeal for Secular Israelis13.

Maybe Secular and Traditional Israelis look up to Haredis only regarding matters of family life, even though that seems somewhat contrived to me. Or maybe the memetic theory does not require Haredi involvement. Perhaps only the Dati influence Israeli society at large. The Dati show reduced mixing as their share of households increases, but the effect is weaker than for Haredis, and not enough for me to conclude they mix very little with other groups14.

To summarize, I find no evidence for what I consider a precondition of this theory in the Haredi case: social interaction between them and the rest of society. There seems to be some mixing between Datis and other Israeli communities, but I’m not sure if it’s enough to influence how other Israelis form and grow their families.

Moreover, I don’t think I’ll be able to confirm or reject the theory by further probing the proposed mechanism of mimetic transmission. Instead, I’ll shift my focus to the outcomes of this mechanism, which will be the subject of my next post.

[UPDATE: I’ve published two follow-up posts focused on other measurable aspects of Israeli family life and how they relate to the mimetic theory:

You can think of this post as addressing the mechanics of the theory and the follow-up as addressing the expected outcomes of the theory]

I feel like I’ve moved up one step in my “career as a writer” after saying that one of my posts is cool. Am I getting smug? (by the way, thank you for subscribing and don’t be afraid to leave a comment calling out anything dumb I write).

I should clarify that, as far as I can remember (my memory is awful), I actually came across NonZionism’s article through an Astral Codex Ten post, Links For September 2024 (point 5).

He also looks at theories number one (existential threats, though he presents it as nationalism) and two (pro-natalist policies), and finds them them lacking.

There might be some exceptional cases where members of a household belong to three or more different groups, but I’ll ignore those rare cases.

If we drop the “contiguous” groups assumption would only widen the gap, from a 2:3 ratio (Arab to Jewish possible settings) to an even more uneven 3:6 ratio.

Warning: mathematics ahead. Let’s assume probability P of mixing is the same for every religiosity level. The same for a member of group A to mix (form a household) with a member of group B, than for a member of group B to mix with a member of group A, etc. If num(A) is the number of members of group A, we get the number of members of group A who mix with members of group B by multiplying numbers of members by P (you could think of P as actually the square of a probability q): mixed (A,B) = P*num(A)*num(B)

If we naively split the Jewish population in four religiosity groups of equal size (25% of population each) and the Arab population in three equal-sized groups (33.3% of pop each), the resulting numbers of Mixed households would be P*0.188 (Jewish) and P*0.218 (Arab).

The Arab Mixed vs Secular plot does not look as random. See below.

If P = 1%, and Secular population is 50k, that means 500 mixers; if Secular population is 100, that means just one mixer.

I understand Datis and Haredis don’t generally like curvaceous, but I don’t believe that’s the explanation here.

R² = 0.77. A very strong linear correlation.

Many careers in Israeli politics owe their existence to military presige.

I could only find six yeshivas in Israel that are not affiliated with the Orthodox (Dati) or Haredi communities. Four operated by the Jewish Movement for Social Change (BINA), and two affiliated with the Conservative/Masorti community: the Conservative Yeshiva at the Fuchsberg Jerusalem Center and the Schechter Institute of Jewish Studies, also located in Jerusalem.

"Maybe Secular and Traditional Israelis look up to Haredis only regarding matters of family life, even though that seems somewhat contrived to me."

I think I will write a response, but to clear up the most basic point, the theory does not state or imply in any way that the secular population look up to or are influenced by Charedim, because this is obviously not true. The theory states that Charedim influence the more observant/pious parts of the non-Charedi religious population. As to how this happens, I actually think it is really obvious to anyone who is familiar with religious communities in Israel, but I accept that I can't just assert that, so I'll have to explain it for people who aren't.