The dubious effect of religiosity on the fertility of an Israeli population

The mysterious fertility of Trad wives of Umm al-Fahm.

As you probably know already, the topic of fertility is one that particularly interests me, and having read many times about Israel’s exceptionally high fertility, close to three children per woman1, I’ve long wanted to take a closer look at Israel’s data.

At first glance, a Total Fertility Rate (TFR) of 3.0 doesn’t seem so high - it ranks only 59th worldwide - but it’s unheard of for a developed country. This unsurprisingly elicits curiosity and has spawned many theories trying to explain Israel’s remarkable fertility, some of them connected to the conspicuous religiosity of certain Israeli communities.

The significantly higher fertility of Ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) Israelis compared to the Very Religious Dati, who in turn have a substantially higher fertility than secular Jews, seems to imply a causal role of religiosity, with greater religiosity positively correlated to increased fertility. You might even say there’s a weak “religious hypothesis“ which states that higher religiosity is correlated to higher fertility, and a strong “religious hypothesis” stating that greater religiosity causes higher fertility.

Luckily, Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) keeps track of the religiosity of the population for every locality, allowing us to see the share of households that are secular, traditional, religious or very religious, and ultra-religious in each Israeli town. The meaning of each of these four categories is fairly well-established, along with their applicability to Jewish and Muslim citizens. For instance, the ultra-religious category only applies to Haredi Jews, not to Muslims or Christians.

Leaving aside the few mixed towns, almost all Israeli cities are either overwhelmingly Jewish or overwhelmingly Arab2. This partly explains why Arab Israeli cities concentrate in three clearly separate regions: a northern one in the historical region of Galilee (Haifa and Northern districts), the centrally-located Triangle along the West Bank border, and a southern one inhabited by Israeli Bedouins3.

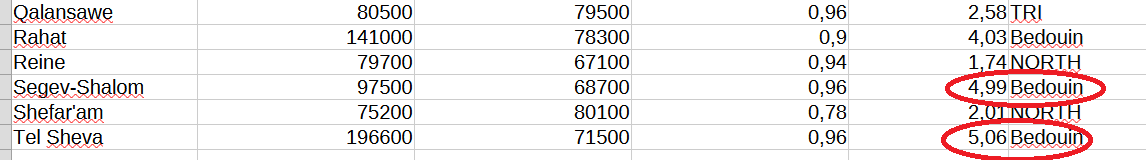

In total, 44 Arab cities with more than 10,000 population are spread across these three regions4, with TFRs ranging from 1.74 to 5.83. I now want to examine the relationship between religiosity and fertility using the Total Fertility Rate and religious composition statistics that CBS publishes for these 44 cities5.

Recall that the ultra-religious category is only used regarding Jews, not Muslims, thus the three categories which CBS applies to the population of Arab cities are (in decreasing order of religiosity): Religious / Very Religious, Traditional and Secular. Households with members from different religiosity categories are rare, as you can see in the following screenshot.

First and second tries

My first attempt to explain the fertility rates of Arab cities naively assumed that TFR depends on the percentage of Secular, Traditional and (Very)Religious households in each city. The multiple regression model I ran, with the three percentages as independent variables, was disappointing: none of the three variables had p < 0.056, which suggests fertility can’t be explained by religiosity.

This is not the end of the story, though. A very noticeable pattern in the data is that Bedouin cities show substantially higher fertility rates than Northern or Triangle cities (roughly 4.7 children per woman7), which may explain why we don’t see an effect of religiosity on fertility. It might be that the effect of religiosity is smaller than that of (high fertility) Bedouin culture, and we need to explicitly include Bedouin culture as a variable in the model to separate the two effects.

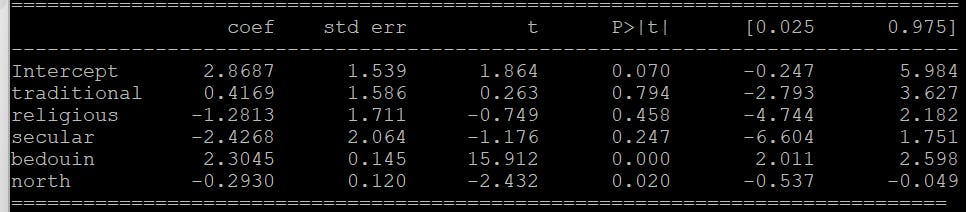

To ensure the model also captures any fertility-influencing cultural differences between Northern and Triangle cities, I defined a second binary (dummy) variable that distinguishes between them (1 = Northern, 0 = Triangle or Bedouin) and re-ran the model with these two new binary variables. The coefficient of determination (R²) increased from 0.211 to 0.9178, indicating the new model is pretty good at explaining fertility across Israeli Arab cities.

The results, unsurprisingly, show that the Bedouin variable has a significantly larger effect on TFR than the Northern variable. They also reveal that religiosity has no predictive power on fertility even after controlling for regional differences in culture (no statistical significance). Maybe I should add another variable to the model?

In comes the income

As you are probably aware, there is a very well-established negative relationship between income and fertility. As Wikipedia says9:

There is generally an inverse correlation between income and the total fertility rate within and between nations.

Maybe the fact that I haven’t yet controlled for income is masking the effect of religiosity on TFR?

The CBS reports two median income values for each city: one for the self-employed and one for employees. Since self-employed median income doesn’t have any effect on fertility while employee median income does, the latter is the one I’ll use from now on.

But before talking about the effect of median income on fertility, I should mention that including three variables (Very Religious, Traditional, Secular) that consistently add up to “nearly” 100%10 might be a bad idea because it can produce multicollinearity, and multicollinearity is bad.

So, instead of showing you the results of an updated model with all three religiosity variables plus median income, I’ll show you the outcomes of the three possible updated models that result from dropping one religiosity variable while keeping two. Here they are, with p-values (“P>|t|“) and coefficients for each of the five variables (two religiosity, two regional, and median income).

You can see that one religiosity variable, percentage of Traditional households, reaches statistical significance in the two models where it is included11, suggesting there might be a real effect there (I’ll discuss the other two variables shortly, but for now let’s focus on Traditional).

The higher the share of Traditional households in a city, the higher the TFR. Going from a 25% share to a 75% share Traditional would raise TFR by roughly 0.8 children. And given that Traditional people are more religious than secular people, this confirms that greater religiosity raises fertility, right? Well, before definitely concluding that religiosity increases fertility, we should take a look at the other two religiosity categories.

Recall that the most religious category is Religious / Very Religious. If greater religiosity increases fertility, as the previous result would seem to imply, then an increase in the share of Very Religious households should have an effect at least as large as that seen for an increase in the Traditional share.

Looking at the first and third regression models, the ones that include the Religious / Very Religious variable, we first see no effect (p = 0.815) and then what appears to be a highly significant effect (p = 0.001). But this seeming highly significant effect is the wrong sign. If religiosity increases fertility, the coefficient for the religious variable in the third model should be positive, not negative. This would appear to suggest that greater religiosity lowers fertility.

Even weirder, the Secular share of households predicts lower fertility, but only in the third model. This seems to contradict what the religious variable suggests in that same model.

Not really a conclusion

I’m not sure what to make of this. What is clear is that I find no robust relationship between religiosity and fertility. Maybe because my models are incomplete? maybe I don’t have enough data? If there was a clear and strong link between higher religiosity and higher fertility across Arab Israeli cities, I would have expected to see it in these models. But I don’t.

What I can conclude is that culture does have a strong effect on fertility. Beyond the well-known negative effect of income on fertility, it’s Bedouin culture that clearly explains the vast majority of the remaining variation in TFR among Arab cities.

Given the results I’ve just presented - and the fact that I’m not an statistics expert - I would greatly welcome feedback regarding the model I used and any obvious blunders I might have made.

I intend to continue exploring this data for a while, and if I do find anything else of interest, I’ll report it in a follow-up post.

(UPDATE: After digging deeper into the data, I arrived at something more concrete:

The Secular share of population is now a strong predictor of fertility: the higher the share, the fewer children per woman.

And the Traditional and Religious shares only appear to be good predictors when the Secular variable is omitted from the model, which makes me think their predictive power is only due to their sum (Traditional+Religious) being strongly negatively correlated to Secular.

Being religious or non-religious does seem to impact Arab Israeli fertility: religious households have more children than secular ones, after controlling for obvious factors. But the level of religiosity among religious Arabs does not have any effect on their fertility.)

Wikipedia says it was 2.85 in 2023, while Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics gives 3.03 for the 2021-2023 period (3.11 among Jewish women).

Mixed cities are those with more than 10% of the population registered as “Arabs” and more than 10% of the population registered as “Jews”.

A tricky case is Bir al-Maksur, a city located in the Northern District but populated by Bedouins. For this analysis, I will classify it as a Northern city.

I’ve excluded cities with a Druze majority or significant minority (Abu Sinan, Isfiya, Maghar, Daliyat al-Karmel, etc.).

They were: 0.716, 0.506 and 0.443. Since the shares of Religious / Very Religious, Traditional and Secular households nearly add up to 100%, it might be advisable to drop one of the three variables to avoid multicollinearity. This results in “statistically significant” values of p, but the explanatory power of the model remains pretty bad: R² = 0.208.

The Bedouin TFR could be much higher than that. My estimate of 4.7 derives from the population settled in cities with more than 10,000 population, but a large part of the Bedouin population lives in unrecognized villages.

R² measures the proportion of variance in the dependent variable explained by the regression model. It ranges from 1 (perfect fit) to 0 (model explains nothing).

“Nearly” is between 79.9% and 99.6% (average 92.8%).

To be clear, if I create the three possible models before including the median income variable, the same variables reach statistical significance (with similar values of p) as when creating the models after including income.