Marriages of the parish of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception of Agaete 1614-1925

What the historical marriage records of the Canarian town of Agaete tell us about Canarian society. And how they relate to Venezuelan births.

Well, I haven’t taken any pictures of the town of Agaete (googling them would be cheating), a charming town in the island of Gran Canaria, but I have taken pictures of several charming towns in its sister Canarian island of Tenerife, so enjoy.

Yes! I’m finally here in the Canary Islands.

And I regret to report that the Spanish Canarian accent is slowly dying - faster in the cities than in the countryside (or what passes for countryside with so much tourism in every corner of the islands). In a way, finding so many Venezuelan and Cuban immigrants around here makes me happy because at least I get to hear the closest thing to an authentic Canarian accent that you can find.

The connection to Canari America can be seen everywhere, from the countless Cuba streets, Uruguay squares and Venezuela avenues, to the frequent references to the “Indies commerce” in museums and historically significant sites.

The focus of this post, though, is not the natural beauty of the Canaries or the long relationship between the archipelago and its American offshoots. What this post is really about is a recently published book called Marriages of the parish of Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception of Agaete 1614-1925, by Javier Gil Pérez.

Note that I haven’t read the book yet. I’ve only read a short interview with the author, recently published by a Canarian newspaper, yet I thought the piece was so interesting and illuminating that it merits its own post.

The book collates a list of 3,153 marriages which took place in the parish church of the town of Agaete between 1614 and 1925. This large dataset enabled the author to analyze the recorded marriages in detail, finding patterns, some expected and some surprising, which are likely applicable to most Canarian towns during the relevant historical period. Among the expected, a high degree of endogamy in the town:

The statistical analysis shows a high rate of dispensations, which are permissions granted by the Bishopric through the parishes, when the spouses were cousins, up to the fourth degree. That is, when they shared common great-great-grandparents. And in a town as geographically isolated as Agaete was 120 years ago, endogamy was very common within the municipality.

The author also notes that certain surnames of spouses and spouses’ parents show up more often, and lists the ten most frequent ones. Some of these are very common patronymics found throughout Spain (e.g. García, González), but others can be described as distinctively Canarian given their much higher frequency in the archipelago than on the Spanish mainland: Armas1, Rosario, and Sosa.

He then talks about the relative decline, and even disappearance, of certain surnames in Agaete2, while also touching on the history of Canarian migration to the Americas:

The surname Palmé, which was once considered unique to Agaete, has disappeared. In the book you’ll see its origin: a man from La Palma was known in the town as “Palmé,” and this name was passed down to his descendants as a surname. There’s a curious story from the early 20th century about the wealth of a married couple from Agaete who emigrated to Cuba and both died, without children. A call went out in Agaete for relatives to come forward and claim their inheritance. Many changes were then requested at the Bishopric to add the surname Palmé to their genealogy.

Also tangentially related to Latin America is his description of how indigenous Canarians adopted Castilian surnames:

The indigenous [Guanche] people were baptized with surnames that were mostly Castilian. For example, a surname like Lugo, which has been mistakenly thought to derive from the Adelantado Alonso Fernández de Lugo, actually comes from baptized indigenous people. Hernández, from Fernando Guanarteme, is also an example of this. His direct descendants, nephews, and cousins take the surname Hernández. Another surname very common in Agaete is Sánchez, through a relative of Fernando Guanarteme, Hernán Sánchez de Bentidagua, who was the royal mayor of Agaete in the early stages of colonization.

Yet, in my opinion, the most interesting bit comes near the end of the interview, when Gil Pérez talks about single motherhood and foundlings in Canarian society:

It also strikes me that, regarding marriages, there are over 300 spouses who were children of single mothers, in a society so closed and influenced by religion. We [also] have documented cases of foundlings or Santana children, who were placed in cradles, and these help us understand the social reality of women and children in those centuries. When mothers were single, the children took their mothers’ surnames. There were certain social stigmas. But, in my opinion, the connection with the port of Las Nieves, open to Europe through the export of sugar from the mills, made Agaete, despite its limitations, a more open town than those in its surroundings.

That is 300 spouses out of more than 6,000. Very roughly a 5% illegitimacy rate, which doesn’t seem remarkable in the Spanish context3. But his mention of foundlings and Santanas did caught my attention. Spanish foundlings - newborn children abandoned by their mothers under dire circumstances - were usually given the surname Expósito (exposed) by the hospitals and religious institutions that raised them. And, in addition to Expósito, different regions of the country had their own local variants of foundling surnames. In the case of Gran Canaria, where Agaete is located, the surname Santana was commonly given, taken from Saint Anne, patroness of the cathedral church of Gran Canaria’s capital, Las Palmas.

If we use these two surnames as a proxy for the prevalence of foundlings in different Spanish regions, the Canary Islands does seem exceptional, showing by far the highest frequency of the surname Expósito4. The surname Santana is of course more common in the Canaries5, where it originated, than in other regions, but we can tentatively compare its frequency there to that of other local foundling surnames within their respective regions6:

Santana (Canary Islands, especially Gran Canaria): 1 in 45.

Deulofeu (Catalonia, especially Barcelona and Girona provinces): 1 in 13k.

Gracia7 (Aragón): 1 in 98.

Trobat8 (Balearic Islands, especially Mallorca): 1 in 4.7k.

As you can see, only the Aragonese surname Gracia comes close to the high frequency of Santana. Yet, at the same time, Aragón has the third-lowest prevalence of the Expósito surname among Spanish regions, which makes me think that illegitimate births - which were likely highly correlated to the number of foundlings - were substantially lower in Aragón than in the Canary Islands.

In fact, I believe the rates of foundlings and illegitimate births in the Canary Islands were likely the highest in Spain, just like today’s Canarian out-of-wedlock rate, as I noted in my post about the Canari American marriage pattern:

And that would be the end of this post (don’t worry, there’s yet another pretty picture at the end), if I hadn’t remembered some figures from the 1941 Venezuelan census. As you might recall from my post on Venezuelan election results, the regions of Venezuela that experienced the heaviest Canarian settlement show political leanings similar to those of the Canary Islands within Spain, in contrast to the Andean region, which traditionally leans right.

The migration of Canarians to Venezuela did not exactly mirror that to Cuba, due to differences in their geographic characteristics. While Venezuela boasts a lengthy Caribbean coastline, it also features a temperate mountainous region in its southwest…While most Spanish settlers favored the temperate regions (circled in yellow in the [following] map) over the tropical coastal areas (circled in red in the [following] map), Canarians predominantly migrated to the Venezuelan coast and nearby valleys.

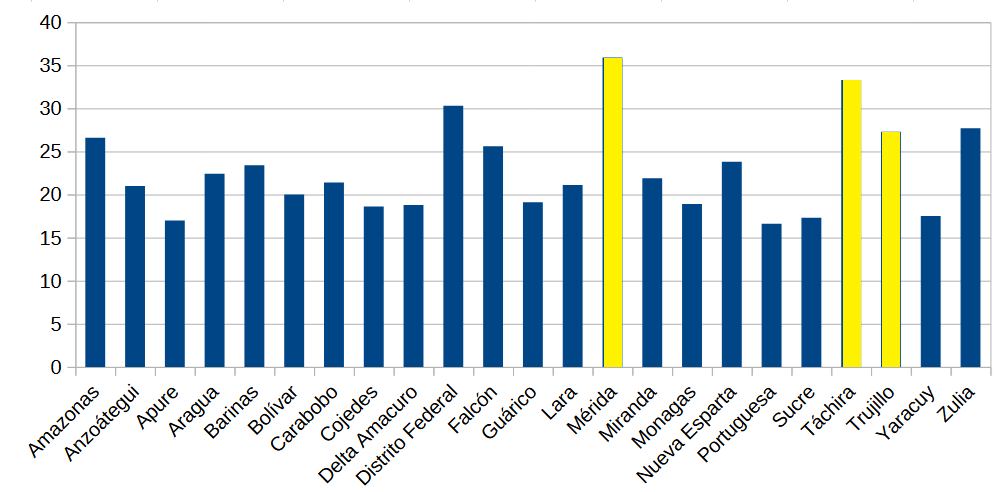

The three states that comprise Venezuela’s Andean region (circled in yellow in the previous map) are Táchira, Mérida and Trujillo. I suggested in that previous post that they tend to vote differently from the rest of Venezuela because they are less Canarian, in contrast to the rest of Venezuela, which to a significant degree inherited its political culture from the Canary Islands. This begs the question of whether we can say something similar regarding marriages and births. And at least in the case of marriages, we can.

These are the 1941 percentages of married individuals (aged 15 and older) for each Venezuelan state:

Excluding the federal district of Caracas - by far the largest city in the country - and Zulia State (the center of the oil industry), the three Andean states have the highest rates of married individuals in Venezuela9.

Regarding the relationship between marriages and births, the Andean region had a slightly higher birth rate than the country as a whole10. This fact, combined with its higher percentage of married individuals, strongly suggests that a larger share of births happened within marriage in the Andean region compared to the rest of the country. In other words, it’s very likely that the rate of out-of-wedlock births in the Caribbean regions of Venezuela was substantially higher than in the Andean region.

And yes, I believe this is because Venezuela’s heavily Canarian-settled regions inherited these marriage and birth patterns from the Canary Islands, just like they inherited other cultural patterns, in contrast to Andean Venezuela.

I now leave you with a lovely picture of Garachico, where in the late 16th century some of the ancestors of Simón Bolívar, the Venezuelan-born liberator of Spanish South America, were born.

That’s Armas as in Ana de Armas, the Cuban-born Spanish (and American as of 2025) actress. The surname Alamo might also qualify, though it’s more common in the Spanish mainland than the other three.

Funny enough, one of the distinctively Canarian surnames that Gil notes has declined in Agaete is Cubas. Like the heavily Canarian-settled nation (island nominative determinism?).

The rate of illegitimate births in Spain during the relevant period appears to have varied between 5.1% and 6.5% . Source: The European Demographic System, 1500-1820, Michael W. Flinn, 1981, Table 6.1.

The frequency of the surname Expósito in the Canary Islands is approximately 1 in 400, compared to 1 in 800 in Andalusia, the region with the second-highest prevalence. Source: Forebears.io.

Although clearly more frequent in Gran Canaria, where Saint Anne cathedral is located, than its sister island of Tenerife, where Expósito is the more common one.

Another local variant appears to be the Galician surname Caridad, derived from the Hospital de la Caridad (Charity Hospital) in La Coruña. It seems to be common only in the province of La Coruña, so I took its frequency for the whole of Galicia, assumed all occurrences are confined to that province, and arrived at a rough provincial frequency of 1 in 3.2k.

This surnames originates from the hospital of Our Lady of Grace (Nuestra Señora de Gracia) in Zaragoza, where foundlings from the whole region of Aragón were raised.

Trobat means found.

Looking at the same statistic for the capital cities of each state (page 59), marriage rates in the Andean capital cities are high but not exceptionally so. This suggests to me that the difference in marriage patterns between Andean Venezuela and Caribbean Venezuela was largely a rural phenomenon.

In 1950 (couldn’t find figures for 1941) the estimated birth rate of the Andean region was 48 per 1,000, while the same rates for the Central region and all of Venezuela were 39.8 per 1,000 and 42-43 per 1,000 respectively. Source: 1950 census, “Tablas de mortalidad para ambos sexos de la Región Central y de la Región Andina“.

Javiero, I am always delighted by your relentless obsession with (1) the Canary islands and (2) rigorous analysis of data.

As someone who is similarly obsessed with (1) the Dutch Caribbean islands and (2) also data, I'm especially excited by your analysis of overrepresented surnames. Here on my island of Saba, there are two massively dominant surnames, Hassell and Johnson. Even though Johnson is a common English surname, and Hassell is a somewhat common Dutch surname (our island was colonized by both these countries) at some point), these names are much more common here than in the English or Dutch areas they are the most common today.

Now, I want to find out if I can get my hands on marriage and birth names records from here. Thanks for inspiring me!