Why Argentina is not rich. Not enough immigrants?

Argentina is (not anymore) a country of immigrants.

Most people are familiar with the image of Argentina as a country of immigrants, and I agree that is an image based on real facts to a large extent. To quote Wikipedia:

Since its unification as a country, Argentine rulers intended the country to welcome immigration…. The majority of immigrants, since the 19th century, have come from Europe, mostly from Italy and Spain.… These trends made Argentina the country with the second-largest number of immigrants, with 6.6 million, second only to the United States with 27 million.

But this image might be an oversimplification that distorts the social and demographic reality of today’s Argentina, driving people to think that the economic decline of Argentina from that golden age where millions of Europeans arrived into the country attracted by some of the highest wages in the world to the middle income country that is 21st century Argentina, is a puzzle in search of some complex explanation.

I’ve already partially explained why this is not a puzzle in a previous post and, as I mentioned in that post, Argentina’s economic decline matches, with a delay, a large change in its immigration policy starting in the 1930’s. I now intend to explore the immigration policies and history of Argentina in more detail.

I wouldn’t say that Argentina’s policy became anti-immigration in 1930’s but it certainly stopped encouraging potential immigrants to choose Argentina as a destination like it had before. No more promotion in source countries, no more land schemes to establish agricultural colonies.

And every time an opportunity to recruit new immigrants came along, Argentine governments dutifully wasted that opportunity.

In 1939 the victory of the nationalist forces in the Spanish Civil War compelled hundreds of thousands of Spaniards to take the path of exile, and the prospect of living in French refugee camps for months or years.

With the last big wave of Spanish migration to Latin America having ended so recently and the specter of a new war looming in Europe, it was no surprising that many Spaniard refugees saw Latin America as an appealing haven and that several Latin American countries reacted to this humanitarian crisis offering to take in thousands of those fleeing from Spain.

What might come as a surprise is just how few of the more than 400,000 refugees were ultimately welcomed into Latin America. Mexico, the country that welcomed the most Spanish refugees by far, received between 30,000 and 50,000, while Chile received a bit more than 3,500.

It’s difficult to find the number of migrants for each country, but the total seems to be much less than 100,000, and assuming the proportion of notable people among all refugees who migrated to each Latin American country is the same, Argentina probably received between 9,000 and 15,000 Spanish refugees in 1939 and the following years. That is no more than four percent of the total at the most. These were people coming from one of the two most important recent sources of immigration to Argentina, with a majority of them coming from the most industrialized regions of Spain (Madrid, Basque Country, Catalonia), and the Argentine government took pains to discourage them from coming to Argentina.

The Argentine authorities seemed reluctant to welcome those passengers that were supposed to continue their journey to other countries, forcing them to stay onboard the ship until their departure towards their final destination… the government was accused of ignoring its traditional policy and denying asylum to renowned Republican intellectuals. Under the pressure of public opinion the government was forced to allow those Spaniards who were in transit to disembark.

Later on, when millions of displaced persons were stuck in refugee camps in Europe after the Second World War Argentina took in a measly 30,000, even though the cost of passage was already funded by the UN’s International Refugee Organization.

Then in the years 1962-1964, when around a million Pieds-Noirs and Harkis were forcefully expelled from Algeria, Argentina made very little effort to welcome this uprooted people. The Pieds-Noirs were the descendants of French, Spanish, Italian and Maltese settlers who began arriving in Algeria around the 1850’s and 1860’s, and despite the similar origins to previous European immigrants and the support of the French state only a few hundred Pieds-Noirs succeeded in resettling to the South American country in large part due to a lack of Argentine support1:

The National Agrarian Council of Argentina, charged with this task at the beginning, is incapable of assuming it and hardly hides it. It was taken over in 1965 by the National Migration Directorate responsible for ensuring the implementation of the Franco-Argentine agreement. The French government, aware of the serious difficulties and lamentable failures of the first colonies, decided in 1965 to delegate to this Service a Permanent Technical Assistance Mission of the B.D.P.A. who has since ensured liaison between the settlers, the Argentine authorities and the French embassy.

And due to the narrow focus on sending only Pied-Noir farmers - no more than 10% of the total Pied-Noir population - who were supposed to develop marginal and uncultivated lands.

Errors, lack of foresight, misunderstanding and chicanery mark the history of the colony. We paid in dollars for the property at a time when the dollar was 150 pesos; today it is worth 350 [in 1968], but the price of agricultural products is far from having doubled and there are still four half-yearly payments, two of which are late, to be paid... in pesos!

Last chance?

The next big chance for starting a new wave of immigration, at least if we assume a preference for immigrants of European ancestry and culture, came in the 1990’s with the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Suddenly any immigrant friendly country could have its pick of hard working foreigners from what is now the fastest growing country in Europe in the last three decades, from the highest per capita motor vehicle producing country in the world, or from any of the other 10 former communist countries that as of 2023 have a higher GDP per capita than Argentina.

What was the reaction of Argentina’s government to this opportunity?

I’ll quote Wikipedia:

In March 1993, Argentine Foreign Minister, Guido di Tella, while on an official visit to Hungary stated that Argentina was capable of receiving European immigrants. The next day, the Argentine Ambassador to Romania, published a request in the local media reporting on the initiative based on the statement from the Foreign Minister, and the following day 6,000 Romanians were stationed at the door of the Argentine embassy in Bucharest requesting applications for immigration to Argentina. Within a few days, the Argentine embassy received 17,000 applications for immigration, however, many applicants were not able to meet various requirements and had little money to settle in Argentina. When news reached Argentina, many took to the streets protesting the possible wave of Romanian migrants coming to Argentina and many feared that the migrants would occupy jobs that did not exist or for locals. In July 1993, Romanian President Ion Iliescu paid a visit to Argentina and met with President Carlos Menem to discuss possible Romanian immigration to Argentina. In the end, only a few hundred Romanians were granted visas to immigrate to Argentina.

This episode, confirmed by other sources, doesn’t just prove the lack of a policy for attracting highly skilled Eastern Europeans willing to go to Argentina. It also shows the changes in the social and political environment - politics in Argentina is to a large degree mob politics - with respect to immigrants. It’s now the case that potential immigrants from regions with a history of high economic development are not encouraged to migrate but looked at with distrust.

Also notice how in the former communist countries, after 45 years of economic mismanagement and migration restrictions, the name and reputation of Argentina was still so great in the 1990’s that it only took a small advertising effort for tens of thousands of potential immigrants to turn up in just a few days.

Argentina has received a not insignificant amount of migrants in the last few decades, close to one and a half million in total, but almost all of them have come from neighboring South American countries, mainly Paraguay, Bolivia, Chile and Peru, countries that never experienced the golden age that Argentina experienced. You could say that Argentina has latin-americanized itself again in the last decades.

The myth of dilution

There’s a misconception of Argentina being flooded by immigrants, even more so than the US, to the point where the previous population was diluted into the new population. This idea is inspired by statements of “6.6 million immigrants” and the fact that Argentina’s population was around 1.9 million in 1869, before the great migration started, and had risen to around 8 million by 1914 when the great migration was ending. It only takes some back of the envelope calculation to conclude that the new migrants must have almost completely replaced, or “diluted”, the previous population - think of Australia.

But that is not the case. For starters it’s very difficult to know how many immigrants actually settled in Argentina because many arrived as temporary workers, going back to their home countries as soon as harvest was over or as soon as they had saved enough to now have a comfortable life back home. Permanent settlers - only some of them agricultural settlers because of how few agricultural colonies were established - were only a fraction of those 6 million.

Also, not all immigrants had an impact in Argentina’s current population by having children (and eventually grandchildren) in their new country. This is partly the result of a very skewed migrant population where males were over-represented compared to females. The next table shows the proportions of males and females in the total population for several countries in the Americas at the beginning of the 20th century, when they were receiving large immigration flows.

As you can see, Argentina had the most male-skewed population at the beginning of the 20th century due to the highly male-skewed immigration that it received2.

A back of the envelope calculation assuming half3 of Argentina’s population in 1914 were adults would result in a 28.6 to 21.4 male skew for adults, a 7.2% of the total population. Based on the fact that immigrants tended to congregate in certain areas, especially Buenos Aires, we could further assume that two thirds of those excess adult males where immigrants, suggesting that 4.8% of the total population were very lonely immigrant males, the kind that for the most part didn’t have children.

When pondering the effect of the great migration wave on Argentina’s present-day population, that gender bias should make you mentally replace the often quoted phrase 30% of Argentina’s population was foreign-born in 1914 by the similar but not quite the same 26% of Argentina’s population was foreign-born in 1914. A small but not insignificant correction4.

The fact that immigrants congregated so much in certain parts of the country - to the point of jeopardizing their marriage prospects - may seem strange, but remember that the motivation for settling in Argentina was first and foremost economic. As I mentioned in my previous post immigrants were attracted to the abundance of land and the high wages to be earned in the farming and cattle industries associated with that land wealth, but that wealth was not evenly distributed in the Argentinian territory. As can be seen in the following map, the provinces in red are the ones with lots of agricultural land and pastures, and also the ones most populated by immigrants in 19145.

Many male immigrants seem to have traded in the joys of a family and children for economic prosperity.

Another minor correction to the idea that Argentina’s pre-great migration population was swamped by the new immigrants is related to the preference of those migrants for settling in cities. The red provinces of the previous map are also the ones where the largest cities of Argentina are located, including Buenos Aires which was already home to 26% of the Argentine population in 19146. And as is the case in almost every country, fertility in Argentina’s urban areas is lower than fertility in rural areas.

This disparity in fertility rates is also attested by the fact that the rate of married women without children in Buenos Aires in 1914 was 14.8%, while the rate for all of Argentina was 10.5%, implying a lower fertility rate for Buenos Aires. And these provinces, the eight provinces in Northern Argentina with less than 9% immigrant population shown in the previous map, accounted for 13% of the total population of Argentina in 1869, before immigration started in earnest.

Assuming the Northern region of Argentina where few immigrants settled kept a higher rate of natural increase until today, it would mean those Northern Argentinians without an immigrant background will now represent more than the initial 13% of the total population, while those Argentinians with a high immigrant background whose ancestors lived in Buenos Aires (province and city) and Santa Fe province7 in 1914, 56% of the population at the time, will now represent less than 56% of the total population.

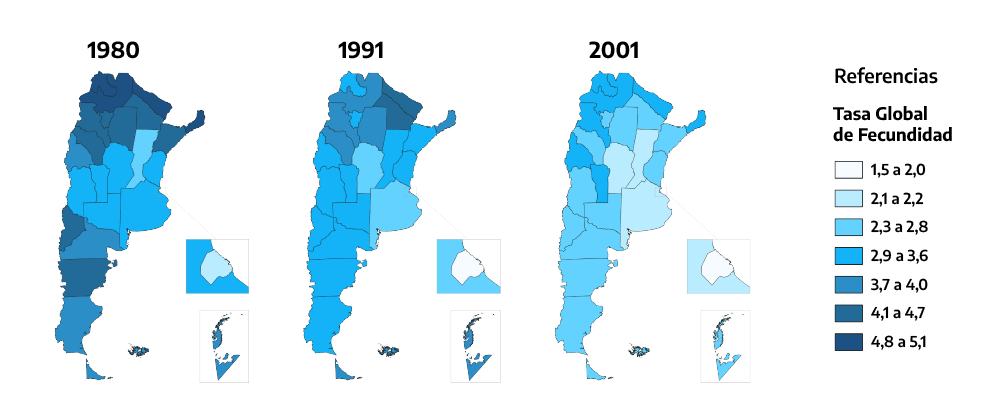

And according to the latest Argentine censuses this is the case.

Doing a back of the envelope calculation8, that original Northern Argentina population (13% in 1914) would now be almost half the original population of Santa Fe and Buenos Aires region (the 56% in 1914). Assuming both populations remained distinct even after the migration of many Northern Argentinians to urban areas, and assuming the population of the rest of Argentina (which was 18% immigrant in 1914) had an average fertility during the next three generations, the descendants of the 30% immigrant population of 1914 would now be just 24% of the total population.

Again, this is a small but not insignificant correction. And you should mentally replace the phrase 30% of Argentina’s population was foreign-born in 1914 by the phrase 21% of Argentina’s population was foreign-born in 1914 in order to have a better idea of the impact of the great migration wave in today’s Argentina.

The idea that Argentina might become once again one of the richest countries in the world, like it was at the beginning of the 20th century, is mostly based on a misunderstanding of the reasons why Argentina was so economically successful back then.

One of those reasons was the enormous land wealth Argentina enjoyed at the time, a subject I explored in my previous post. Another is the great wave of immigration that transformed the population of Argentina into a much more urbanized and productive society.

But this second reason is an illusion. The transformation brought about by immigration was narrower, in a demographic and geographical sense, than what is commonly assumed and it has partially reverted in the last century due to the demographic causes I have mentioned above.

In October 1964 De Gaulle paid an official visit to Argentina and during this visit the French general and the non-Peronist Argentine president Arturo Illia signed a convention that was supposed to facilitate the settlement in Argentina of those Pieds-Noirs, mostly farmers, who chose to migrate to the South American country. This was just a minor goal of De Gaulle’s visit, considering that Argentina was but one stop in a grand tour of more than 10 Latin American countries with the purpose of reasserting French status as a World power and independence from the US. Peronists viewed the visit as a chance to mobilize its sympathizers in Argentina, chanting “De Gaullle y Perón, tercera posición!” (https://www.clarin.com/viva/dia-masas-peronistas-cantaron-gaulle-gaulle-grande-sos-_0_BRps0RglOX.html), putting Illia’s government in a difficult position, and even putting the French general in harm’s way during a particularly heated rally (https://archive.nytimes.com/iht-retrospective.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/10/06/1964-battle-imperils-de-gaulle/). I suspect the Argentine government didn’t put much effort into the resettlement of the Pieds-Noirs because they never intended to, and only agreed to signing the convention in order to improve relations with France.

I don’t want to go into detail about why this is the case. But the fact that Cuba, whose large immigration was mostly sustained by the large scale and highly capital intensive sugar industry, is the second most skewed country should be a hint.

The real fraction is close to 45% children: http://www.estadistica.ec.gba.gov.ar/dpe/Estadistica/censos/C1914-T1.pdf

The same approximate figure can be estimated from the details of the 1914 census by taking the differences between males and females foreigners for the three largest Argentine provinces plus Buenos Aires (around 480 thousand people) and then assuming two thirds of those excess males would not have children.

Notice that high agricultural potential in the beginning of the 20th century is not the same as high agricultural potential in the beginning of the 21st century. New technologies have made a large part of what used to be considered a wasteland, the Chaco, a very productive land for the farming of Soy and Maize. The province of Santiago del Estero now accounts for 7% of the Soy and 9% of the Maize produced by Argentina, while Chaco province and Salta also contribute a not insignificant amount.

Today it’s 29% of the total population. That might not be an absolute demographic sink but it certainly seems like a relative demographic sink.

I left Tierra del Fuego territory and Santa Cruz and Chubut provinces out despite having a high immigrant population in 1914 in order to simplify the next calculation. Their populations were only 0.5% of Argentina’s 1914 total population.

An Excel spreadsheet actually. Total fertility rate (TFR) in Argentina was 5.2 in the year 1914, around 3.14 during the 1950’s, 3.3 in the 80’s and 2.9 in the 90’s. The difference in TFR between both regions in the 1980’s was around 1.7, and there was already a large difference in fertility between Buenos Aires and the Northwest in 1914 (see source) so I’m using the 1.7 difference for the first two generations, and a 1.5 difference for the third generation (80’s and 90’s). TFRs used are: 4.4 and 6.1; 2.9 and 4.6; 2.7 and 4.2. I also included migration from the North to Buenos Aires in order to keep the proportions between both populations that later censuses show. Assumed fractions of immigrant population are: 0%, 18%, 40%. Real fraction for Northern provinces was 0.9% or less. Sources: https://www.argentina.gob.ar/interior/renaper/observatorio-poblacion/estudios-diagnosticos-y-reportes/natalidad-fecundidad-1980-2019; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Demographics_of_Argentina; Ramiro A. Flores Cruz, “El crecimiento de la población argentina“, page 10; http://www.estadistica.ec.gba.gov.ar/dpe/Estadistica/censos/C1914-T1.pdf

Were Argentina’s pre-1930 European immigrants highly skilled? In the U.S., Italian immigrants in the early 20th century ranked near the bottom of all ethnic groups in terms of educational achievement, which led to unfortunate stereotypes and an early backlash against immigration.