The fall of the Berlin wall and the fall in fertility.

Another look at how restrictions on leisure and access to amenities impact fertility rates.

In a previous post, discussing the impact of Latin American curfews on fertility, I wrote:

…correlation does not imply causation. But the cases I’ve reviewed seem to suggest that imposing restrictions on leisure and socializing activities in a country might increase its fertility rate.

I now want to explore the opposite scenario. What happens when a community or country rapidly abolishes restrictions, creating opportunities for new leisure activities and ways to spend time and entertain themselves?

And for that, we need to take a look at Eastern Europe.

Let’s start with some historical background, from Wikipedia:

The Revolutions of 1989, also known as the Fall of Communism, were a revolutionary wave of liberal democracy movements that resulted in the collapse of most Marxist–Leninist governments in the Eastern Bloc and other parts of the world…The Revolutions of 1989 contributed to the dissolution of the Soviet Union—one of the two global superpowers—and the abandonment of communist regimes in many parts of the world, some of which were violently overthrown.

For the purposes of this piece, that’s just a fancy way of saying that after the revolutions of 1989 Eastern Europeans could now eat at McDonald’s, dance to trance music to their hearts content, vacation in Ibiza, and enjoy a myriad of new leisure activities and entertainment options that were previously non-existent.

Did the political and economic transition have any impact on fertility rates?

Apparently, yes. Correlation does not imply causation, but concurrently with the change of political regimes fertility rates declined in every Eastern European country.

Let’s start by looking at a chart displaying the Total Fertility Rates (TFR) for all former communist Eastern European countries from 1988 to 1995:

A couple of points stand out from this chart:

The general trend is downwards. All countries have lower fertility in 1995 compared to 1988.

A few countries stand out from the pack: Albania, East Germany1, North Macedonia, and possibly Slovenia.

The first point is surprising, especially when viewed through the lens of traditional demographic transition theory:

In demography, demographic transition is a phenomenon and theory which refers to the historical shift from high birth rates and high death rates to low birth rates and low death rates, as societies attain more technology, education (especially of women) and economic development…the existence of some kind of demographic transition is widely accepted in the social sciences because of the well-established historical correlation linking dropping fertility to social and economic development.

Every country in Eastern Europe, with the exceptions of Poland, East Germany and the Czech Republic, had a lower GDP per capita in 1995 than in 1988. So why did fertility rates decrease when there was “no economic development”?

Granted, demographic transition theory does not explicitly predict that an economic contraction should increase fertility, but the observed decrease might challenge the theory, depending on the specific mechanisms2 that trigger fertility decline.

(Note: I hope to write another post to explain in detail why I think demographic transition theory actually predicts the opposite of what happened in Eastern Europe)

Let’s now turn our attention to the second point. Why do some countries diverge from the rest?

Albania and East Germany

Albania experienced a moderate decline in fertility during the 1988-1995 period, similar to all other countries. It’s only peculiarity is that its fertility rate was significantly higher than the rest, which could be attributed to its exceptionally lower income level - the lowest in the sample by far.

East Germany presents a more interesting case. Its income level was mid-range among Eastern European countries. However, unlike every other country, East Germany’s fertility plummeted immediately after the fall of the Berlin wall and its reunification with Western Germany, dropping from a TFR of 1.52 children per woman in 1990 to 0.98 children per woman in 1991.

East Germans did not experience the severe economic downturn that the citizens of other former communist countries experienced:3

On 18 May 1990, the two German states signed a treaty agreeing on monetary, economic, and social union… it came into force on 1 July 1990, with the West German Deutsche Mark replacing the East German mark as the official currency of East Germany. The Deutsche Mark had a very high reputation among the East Germans and was considered stable. While the GDR transferred its financial policy sovereignty to West Germany, the West started granting subsidies for the GDR budget and social security system.

East Germany was one of only three Eastern European countries that experienced economic growth in 19924. And, of course, it was the only country that was quickly absorbed into a well-established free-market economy.

I don’t know of any explanation within demographic transition theory that accounts for what happened in East Germany during the early 1990s. But I know how I would explain it: with the fall of communism and the sudden availability of the leisure activities and lifestyles that West Germans had long enjoyed, East Germans prioritized these new experiences over investing time in parenthood.

Consider all those McDonald’s, nightclubs, and travel agencies. West Germany already had all of those, and it was just a matter of opening up new venues across the former border - no legal, currency or regulatory barriers to slow the process - allowing East Germans swift access to these new experiences.

East Germany was exceptional among Eastern European countries with respect to the speed with which it acquired the amenities of a modern lifestyle, and it was exceptional in how quickly its fertility declined.

The former Yugoslavia

In addition to standing out in the previous fertility chart, North Macedonia and Slovenia share another thing in common: both were part of the former Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia.

Slovenia had the lowest fertility rate among Eastern European countries in 1988, at the start of the analyzed period. Croatia, another former Yugoslav republic, came in second lowest, while Serbia ranked fourth.

In a simplistic take of demographic transition theory, Croatia’s fertility rate seems lower than expected considering it had the fifth-highest GDP per capita among all countries, and we should expect higher income would lead to lower fertility. But Serbia’s fertility rate seems particularly unusual, given that its GDP per capita ranked 13th, well below the average.

Also, notice that North Macedonia’s GDP per capita is only 7% lower than Serbia’s, yet its fertility rate is considerably higher than Serbia’s, standing at 2.22 children per woman compared to Serbia’s 1.82. The most parsimonious explanation for this disparity is that North Macedonia was a more rural country, further away from the nice amenities of the West:

[Slovenian accountant] Meta remembered that she bought only nail accessories, as she went there with the purpose to sightsee, not shop. Meta was a ‘leisure seeker’ who practiced ‘touristic shopping’ and the pastime required a greater amount of free time. When she was exploring the shops in neighbouring Italy, in Trieste or Rome, she did not perceive it as mere shopping, but also as a trip, since she visited painting exhibitions, churches, monuments, etc.5

Although Yugoslavia's republics may not have been among the wealthiest in Eastern Europe, their economic system, characterized by self-management and elements of market socialism, fostered a relatively freer market environment:6

Thus, for example, agriculture still remains by and large in private hands (85 percent) as do the various craft industries (240,000 private individuals engaged in everything from beauty shops and restaurants to repair shops). Such heterogeneity has imparted a unique economic system to Yugoslavia that is regarded by most observers as neither Western nor Eastern.

And Slovenia, as the Yugoslav republic geographically closest to Western Europe7, uniquely benefited from its proximity to the detriment of other pursuits. Its citizens enjoyed the best access to Western amenities:8

The Ossim agreements between Italy and Yugoslavia in 1975 made the Yugoslav-Italian border the most open one between any capitalist and socialist state. From 1962 onwards, Yugoslavs could legally buy and keep foreign-currency and bank accounts. From the late 1950s, travelling abroad became easier because of accessible passports and the establishment of a visa system for leisure travel…Within Yugoslavia, due to the borders with Italy and Austria, Slovenia had a privileged position in terms of access to products from Western capitalist countries and Slovenian consumerism therefore developed to a greater extent than in other republics.

Despite its freer market environment, even mildly consumerist Slovenia experienced a 18% decline in its fertility during this period of time, from a TFR of 1.58 in 1988-89 to a rate of 1.29 in 1995. In fact, four out of the six smallest declines were observed in the Yugoslav republics.9

Summary

To summarize, among Eastern European countries, the Yugoslav republics enjoyed the greatest access to modern amenities during communist rule, and exhibited the lowest rates of fertility. When all Eastern European countries underwent market liberalization10, they experienced the smallest decline in fertility rates.

Also, East Germany experienced the most abrupt economic liberalization, accompanied by the largest drop in fertility.

It’s almost as if the extent and speed of the transition to free markets determined the magnitude of the fertility drop:

Does this align with the correlation between income levels and fertility rates outlined by demographic transition theory?

The countries that increased their GDP per capita during the early 1990s, namely Poland, East Germany and the Czech Republic, experienced a decline in fertility rates. But so did every other Eastern European country, so the answer would appear to be: no.

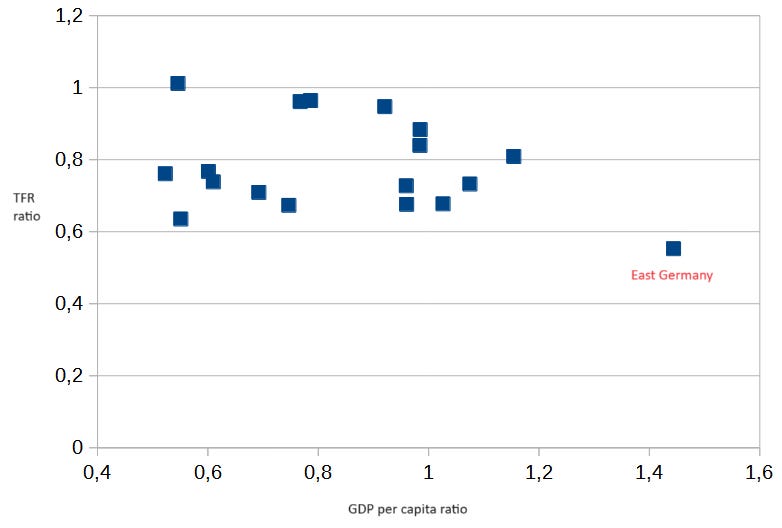

The following chart presents the ratios of variation in GDP per capita and TFR for each Eastern European country:

The correlation between the two sets of ratios is -0.28, a slight negative correlation, implying that increases in GDP, or less severe decreases, are weakly associated with declines in fertility rates.

But this is a spurious correlation caused by East Germany’s ratios. Once I exclude East Germany from the data, the correlation coefficient becomes -0.02, indicating there’s no correlation at all.

It’s the changes in access to leisure, entertainment, and modern amenities that impact fertility rates, rather than changes in income itself.

Increased income provides more resources for supporting children. However, in a free society with endless choices for spending money and time, it also offers numerous alternatives that compete with the joys of parenthood.

Throughout this post, I will refer to the former East German states post-1990 as “East Germany” for simplicity.

Oded Galor (“The Demographic Transition and the Emergence of Sustained Economic Growth“) proposes four possible mechanisms: The decline in infant and child mortality, the rise in the level of income per capita, the rise in the demand for human capital, and the decline in the gender gap.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German_reunification#Economic_merger

I couldn’t find data for 1991, but given the substantial resources West Germany poured into the former East Germany, I consider it unlikely that there was any significant economic contraction.

“Workers becoming tourists and consumers: social history of tourism in socialist Slovenia and Yugoslavia”, Sitar, P. (2020).

“Major Trends in the Postwar Economy of Yugoslavia“, George Macesich, University of California Press.

Distance from each capital to Gorizia, Italy: Slovenia 105 km (65 mi); Croatia 240 km (150 mi); Serbia 630 km (390 mi); North Macedonia 1060 km (660 mi).

“Workers becoming tourists and consumers: social history of tourism in socialist Slovenia and Yugoslavia”, Sitar, P. (2020).

The two other countries were Albania and Hungary. Albania was by far the poorest country at the start of the period, and retained this status by its end. You can’t access these new amenities if you can’t afford them.

I'm not employing the term “market liberalization” in its traditional economic sense, but to denote increased access to amenities.