I’ve previously written a couple of posts on the relationship between time-intensive entertainment and fertility, and how certain communities successfully meet their preference for high fertility by enforcing restrictions on their members' ability to engage in time-consuming entertainment and leisure activities:1

In that previous post about the Amish, I suggested that their high fertility is based not only in a preference for children, but in a preference for children above other pursuits. This preference is realized thanks to the unique Amish social mechanisms that enforce limitations or bans on those other pursuits.

You could think of this as a trade-off, a voluntary one considering that the Amish have the option to leave their community. But what if a community were forced to make this trade-off against its will?

Only dirty subversives would roam the streets this late at night

Argentina is well known as a country that has suffered numerous political crises throughout its history, including several military coups that often led to periods of military dictatorship.

The last such dictatorship began with the 1976 coup, and lasted until 1983. In Grok’s words:

The 1976-1983 Argentinian military dictatorship, known as the National Reorganization Process, was a period of state terrorism marked by the Dirty War, where up to 30,000 people were "disappeared" by the government in its fight against left-wing subversion.

The military regime not only repressed those it considered as its enemies, but also imposed harsh policies that impacted the entire population to facilitate this repression. And one of those policies was a national curfew:

A disruption in the citizens' routines was the coup of March 24, 1976. The curfew was in force until [October] 1983 and the government exercised a system of control and surveillance. The young people, due to their militancy, were the most targeted. Daily habits were changed, meetings that were usually held between friends were put aside, and precautions were taken not to go out at night.2

Setting aside questions of effectiveness, a curfew clearly restricts people's ability to socialize and enjoy leisure time in the company of adults. And indeed, that was its consequence.

Did this curfew affect fertility by making alternative activities to having children - spending time on other pursuits - unavailable or more expensive?

Here is a chart displaying Argentina's Total Fertility Rate (TFR) from 1950 to 2022:

While correlation does not imply causation, there is a noticeable increase in fertility during the years marked by the pink shaded area in the chart, which corresponds to the curfew period.

And this bump doesn’t show up on the fertility charts for neighboring South American countries, like Brazil:

Or Colombia:

Though Uruguay does seem to show a slight bump during the years following the 1973 coup, when it also experienced a curfew:

And in the case of Chile, only the last years of the curfew (1973-1987) imposed by its military dictatorship seem to coincide with a temporary halt in the long-term downward trend of fertility.

What if it’s not a curfew that prevents people from going out and patronizing the establishments where they can enjoy themselves and socialize, but the fact that those establishments are private businesses and, well, we can’t have private businesses anymore?

Only dirty reactionaries would patronize these decadent bourgeois establishments

To answer that question, we have to take a look at Cuba.

After the 1959 Cuban Revolution, the new revolutionary government quickly began to expropriate private properties and assets. Initially targeting those associated with the ousted Batista regime, the focus soon expanded to include those considered as enemies of the new regime, such as Americans and large landowners. Eventually, by the mid-1960s, even small businesses were subject to expropriation.

Nightclubs and bars were closed and their closures would be justified via official accusations that they were epicenters of prostitution, homosexuality, and crime.3

These establishments were now deemed inappropriate for the new socialist citizens the regime was trying to produce:

Rest in peace - cabarets, bars and other venues

We must find new ways of entertainment. We must develop cultural activities, popular dances in appropriate venues and workers’ recreational centers. Through sports we must find wholesome forms of recreation. Bicycle riding, motor biking, camping, trips to the beach, excursions, museum visits, theater, parks, forests, botanical gardens, the zoo, the movies, etc.4

Even grabbing a beer at the corner bodega became impossible:

Suddenly it was sinful and forbidden to go to the corner bodega and drink a beer at the bar by the curb, where all the neighborhood guys used to shoot the breeze and the women would buy the family’s daily groceries5

Did these restrictions and closures affect fertility by making unavailable alternative activities to having and raising children?

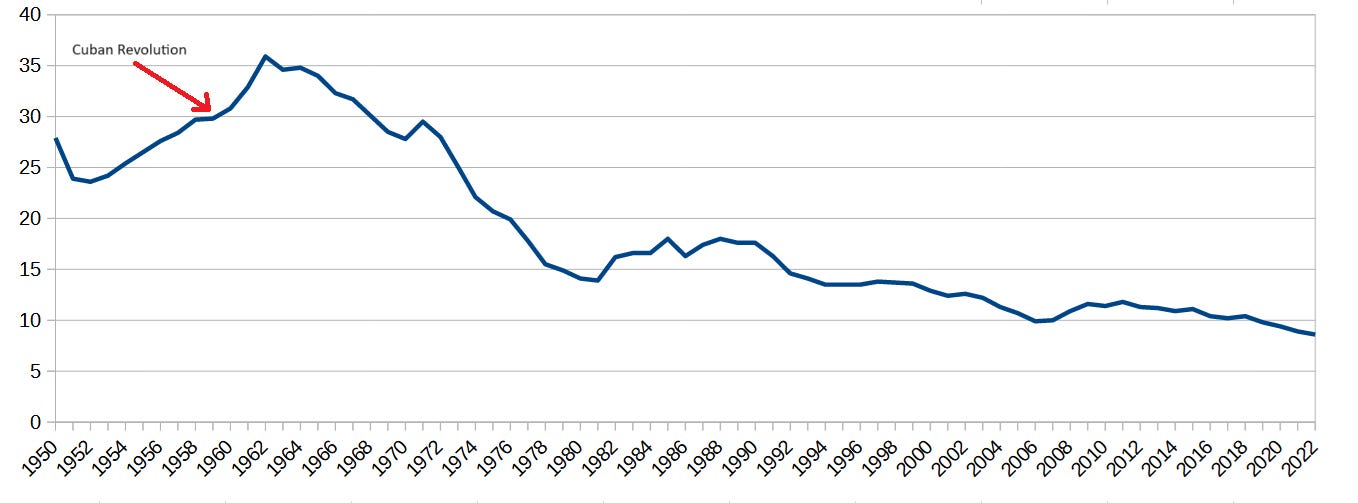

The following chart shows Cuba's Crude Birth Rate (CBR) from 1950 to 2022:

At first sight the answer appears to be yes. Yet, an objection can be raised against this first impression. The objection is that the increase in fertility began a few years prior to the revolution's triumph in January 1959, rather than immediately afterwards.

A partial response to this objection is that Cuba experienced conditions similar to a curfew before the revolution's victory, as was reported by the New York Times:6

Troops escorting vehicles - Curfew set for buses

Soldiers are convoying trucks and automobiles in Oriente and Camaguey Provinces, according to a traveler who arrived here today. Busses are banned from the highways after 5 P.M.7

The situation, unsurprisingly, was akin to a state of war:

Dairy, vegetable, and meat products no longer flowed from the countryside to the city. Prices of basic staples soared and many products disappeared altogether. Sabotage and the destruction of property led to a drop in sugar production. Shortages of gasoline and oil brought railroads, trucking, and sugar mills to a standstill. Telephone and telegraph service across the island was paralyzed. Bridges were out of service, and transportation between Havana and the three eastern provinces was all but destroyed. Manufacturers’ inventories began to pile up at plants…From November 1 to December 31, 1958, about 300 bombs exploded in the Havana metropolitan area.8

Again, correlation does not imply causation. But the cases I’ve reviewed seem to suggest that imposing restrictions on leisure and socializing activities in a country might increase its fertility rate.

I've illustrated this point with examples from Latin American countries, but similar situations are evident in other continents, where countries have experienced an increase in fertility rates under curfew conditions.

[UPDATE: Related to this last point, you might be interested in some of my other posts:

The fall of the Berlin wall and the fall in fertility

The American baby boom and what it reveals about fertility]

After writing my second post on this issue, I became aware of a 2023 post by Alex Nowrasteh which states this hypothesis - dare I say in a much clearer way than I do - in terms of opportunity cost. I highly recommend reading it.

“Cuarentenas y estados de sitio en la historia argentina: qué hizo la gente en medio de epidemias o caos político”, https://www.infobae.com/sociedad/2020/03/19/cuarentenas-y-estados-de-sitio-en-la-historia-argentina-que-hizo-la-gente-en-medio-de-epidemias-o-caos-politico/

From Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Revolutionary_Offensive#Implementation

“Goodbye, My Havana: The Life and Times of a Gringa in Revolutionary Cuba”, Anna Veltfort.

“Goodbye, My Havana: The Life and Times of a Gringa in Revolutionary Cuba”, Anna Veltfort.

Moreover, there was almost no increase in fertility from 1958 to 1959 immediately following the revolutionaries' seizure of power (and the cessation of fighting).

New York Times, October 20, 1958, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1958/10/20/92652226.html?pageNumber=9

“COLD WAR CUBA: HAVANA IN CRISIS — 1958”, Lisa Reynolds Wolfe, https://coldwarstudies.com/2014/02/04/cold-war-cuba-havana-in-crisis-1958/