The effect of (non-)religiosity on the fertility of an Israeli population. Part 2.

There’s really no mystery in the fertility of Umm al-Fahm’s Trad wives.

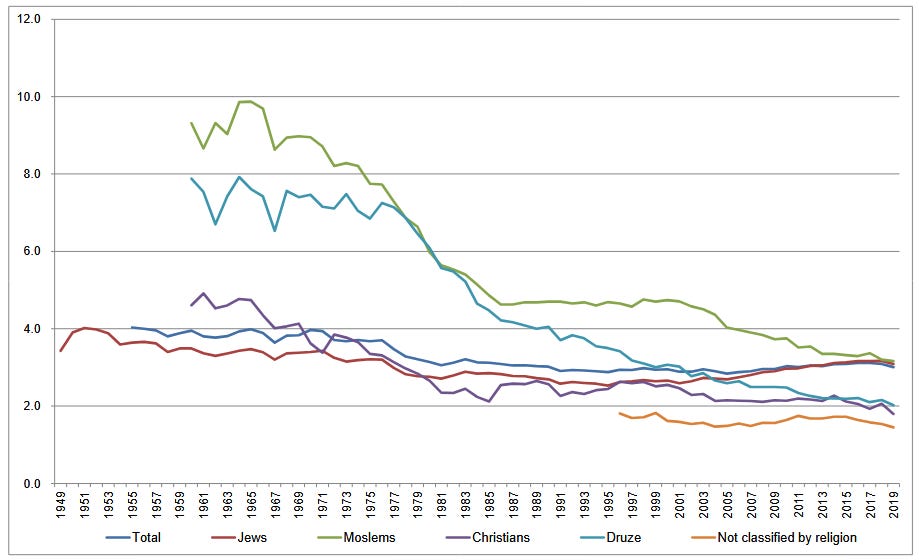

In my last post I analyzed fertility data for Arab Israeli cities and found out that median income impacts Arab Israeli fertility negatively (as expected from the literature), culture and lifestyle unsurprisingly have an effect on fertility, and lastly: it’s very hard to figure out whether religiosity has any effect and in what direction.

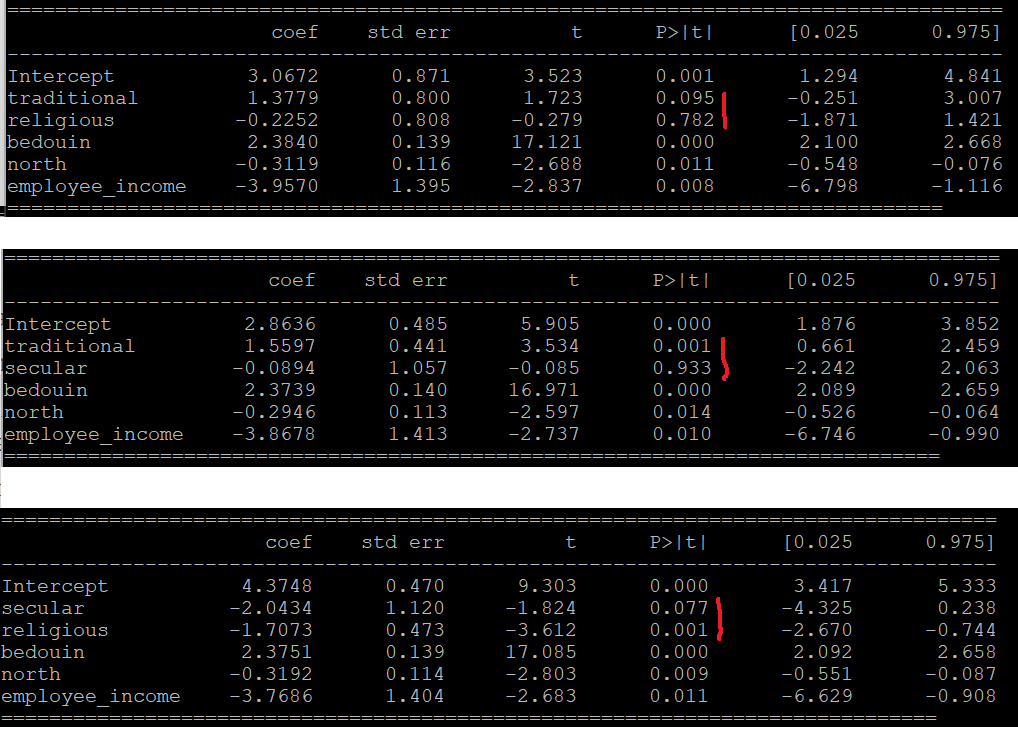

Looking at the first and third regression models, the ones that include the Religious / Very Religious variable, we first see no effect (p = 0.815) and then what appears to be a highly significant effect (p = 0.001). But this seeming highly significant effect is the wrong sign. If religiosity increases fertility, the coefficient for the religious variable in the third model should be positive, not negative. This would appear to suggest that greater religiosity lowers fertility.

Let’s recall that Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) classifies Arab Israelis into three levels of religiosity: Religious / Very Religious, Traditional and Secular. In my previous analysis I tried to find a connection between the population share of each of these religiosity categories in a city and the fertility rate (TFR) in that city. If the “religious hypothesis“1 is true - greater religiosity is correlated with (and possibly causes) higher fertility - then we should have seen the following as a result of that analysis:

A higher share of Secular population lowers the city’s fertility.

Higher Religious / Very Religious share of population should be positively correlated to higher fertility.

A higher share of Traditional raises fertility only if the Religious share shows a fertility-raising effect at least as large as that of Traditional.

I did observe some evidence for the first proposition (Secular lowers…) and no evidence for the second. The third one I intentionally wrote as a conditional statement because, despite noticing a positive effect of the Traditional share on fertility, I did not see the even greater effect that the “religious hypothesis“ would predict for the Religious share of population.

This is why I admitted I was confused by the results of my last analysis. I was unable to decide whether the data supports or refutes what I call the “religious hypothesis“.

A closer look

But after perusing the data more closely, I realized that cities with higher Secular population share usually have a substantial Arab Christian minority. These Christian communities are concentrated in the Northern region of Israel, especially in Nazareth and its environs. Could it be that the presence of Arab Christians in a city - with their own distinctive culture - has a confounding effect?

We already know from CBS data that Christians have a lower TFR than Arab Muslims2. And this holds even after excluding Bedouins (there are no Arab Christians in Bedouin cities as far as I’m aware). It wouldn’t be surprising that the apparent effect of the Secular share is in fact an effect of the Christian population share in each city.

Once I realized this pattern existed, I did the obvious and excluded the six Arab cities with a Christian share of population above 10%3, leaving a total of 38 overwhelmingly Muslim cities to be analyzed using the same regression models from the last post.

And the results of this new analysis are:

The Secular share shows no effect whatsoever now. The only remaining apparent effects are: the Traditional share seems to increase fertility, but only when the other religiosity level variable in the model is Secular; the Religious share of population appears to decrease fertility, but only when paired with Secular4.

I don’t believe these two effects are real, mainly because they both disappear when the second religiosity variable changes. Yet seeing these results convinced me that throwing away the six Arab cities with sizeable Christian populations was a bad idea. There is certainly confounding between the share of Christian population and the percentage Secular5, but dropping six data points from my already small sample risks obscuring the effect of the Secular share of population on fertility.

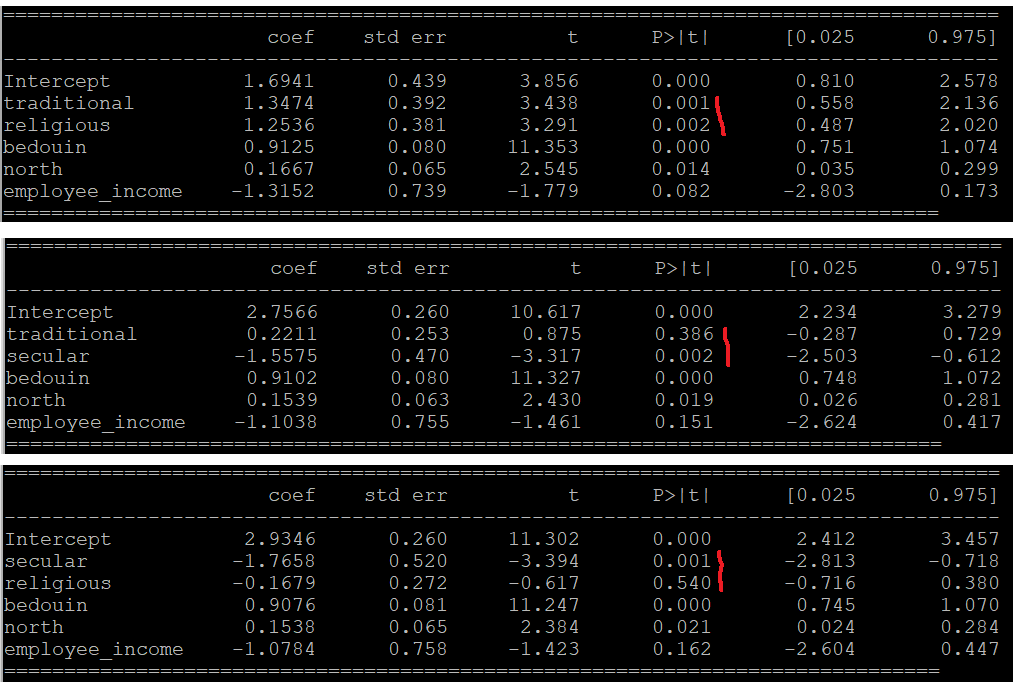

So, instead of dropping data points, let’s expand the dataset. Although the CBS only publishes TFR values for the 44 Arab Israeli cities with over 10k population, it does provide a children per woman (CPW) figure for smaller towns, allowing us to increase the sample size if we switch our fertility measure from TFR to CPW6.

The three new models for predicting CPW use a dataset of 52 towns and the same three pairs of religiosity variables as before. And here are their results.

The Secular share of population is now a strong predictor of fertility: the higher the share, the fewer children per woman.

And the Traditional and Religious shares only appear to be good predictors when the Secular variable is omitted from the model, which makes me think their predictive power is only due to their sum (Traditional+Religious) being strongly negatively correlated to Secular.

Also, if you were paying very, very close attention (I’ll admit that black-background screenshots are not the best way to convey information) you might have noticed that the north variable changed signs. It used to be negative, suggesting the Northern region, where Arab Christians live, has lower fertility. But now it’s positive, suggesting that (maybe) Northern Arab towns have slightly higher fertility.

Conclusion

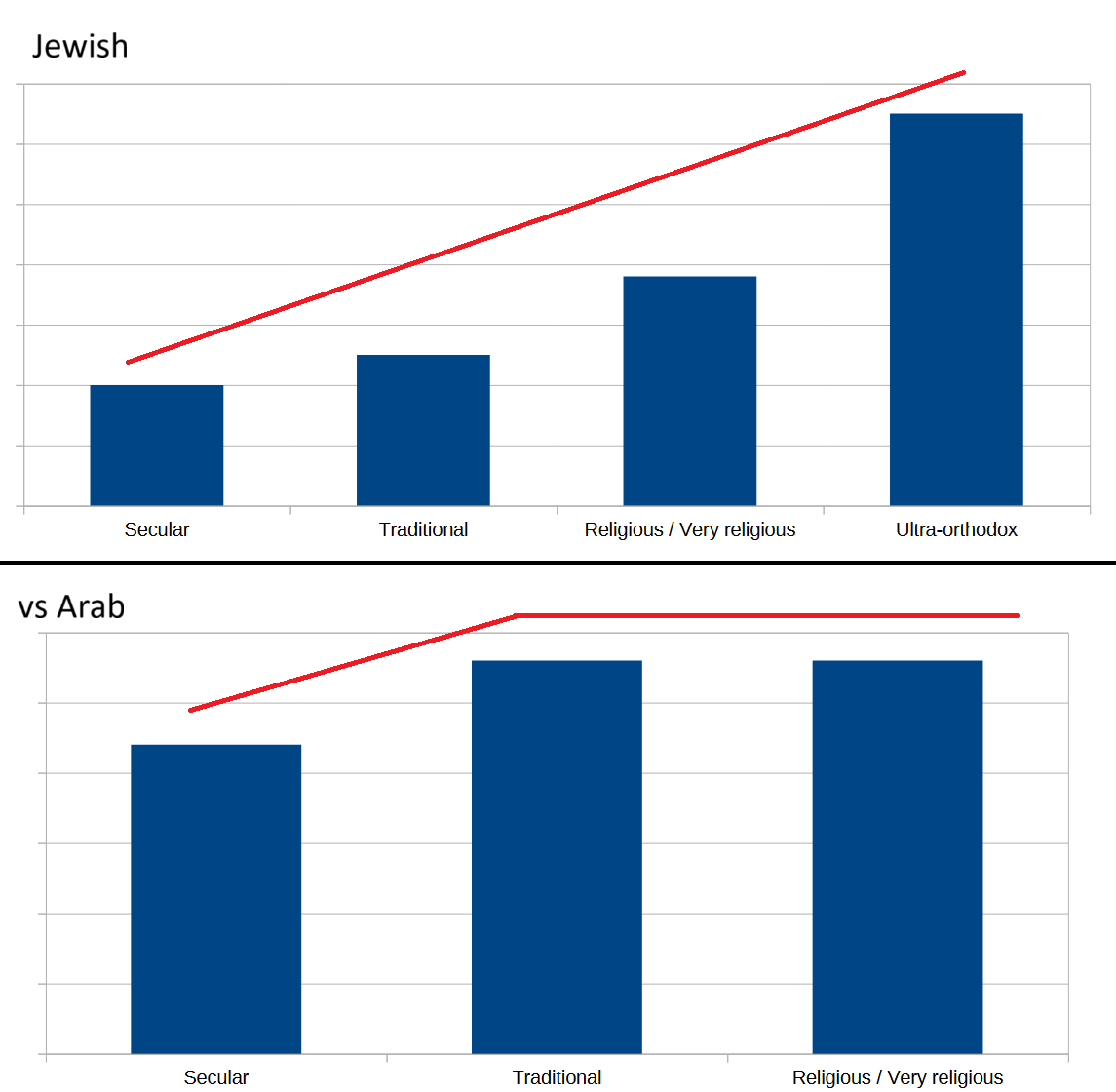

In short, religiosity does appear to affect Arab Israeli fertility but only in a binary way: religious households have more children than non-religious (Secular) ones. Yet the level of religiosity, Traditional or Religious / Very religious, of practicing Arab Israelis doesn’t have any impact on fertility. In contrast to Jewish Israelis, who exhibit a clear increase in fertility for each increase in religiosity, Arab Israelis show no additional fertility increase beyond the religious-vs-Secular divide.

Regarding the “religious hypothesis“, these results cast some doubt on the idea that there’s a simple relation between fertility and religiosity, with the former being a linear function of the latter.

I intend for my next post to address the idea that, in the case of Jewish Israelis, a culture of high fertility rubs off from the most religious group (Ultra-orthodox) to less religious groups, increasing the fertility of each group by the cultural influence of the one above it.

From Religiosity and Fertility in the United States: The Role of Fertility Intentions, Sarah R Hayford, S Philip Morgan, 2009: “we show that women who report that religion is ‘very important’ in their everyday life have both higher fertility and higher intended fertility than those saying religion is ‘somewhat important’ or ‘not important.’“.

Though this includes a small number of non-Arab Christians.

These cities are: I’billin, Yafi, Kefar Yasif, Nazareth, Reine and Shefar’am.

Just to make sure, I also ran a model with all three religiosity variables and none of them reaches statistical significance, while the three other variables (north region, bedouin region and median income) remain statistically significant.

The correlation between them is roughly 0.6-0.7.

Children per woman is not as good a measure as TFR because it’s impacted by the age at which mothers give birth. But if any variable truly has a statistically significant effect on TFR, it should also have a strong effect on children per woman in the same direction.

May I take a moment to let you know how much I appreciate this series--and that this series is the kind of thing you do? I love your curiosity-driven deep dives into data. Thank you.