Short post on Muslim Spain and regional differences

Islamic Spain, Christian Spain and state capacity. Did al-Andalus fall in 1013?

I just finished reading “Muslim Spain and Portugal: A political history of al-Andalus“ by Hugh Nigel Kennedy, and I think I’m beginning to see a pattern in the way Muslim rulers in Al-Andalus confronted the Christian Kingdoms of Northern Spain.

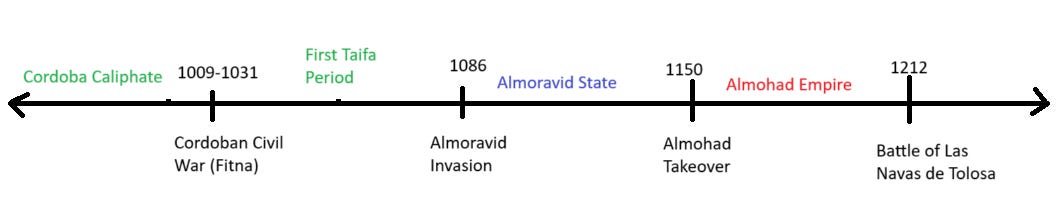

As its title implies, the book delves into the political history of Al-Andalus, Muslim Spain and Portugal, devoting many pages to the rise, apogee and fall of the Caliphate of Cordoba, and the Muslim states that succeeded it: the Taifa kingdoms, the Almoravid Empire and the Almohad Caliphate.

I haven’t come across this pattern explicitly mentioned elsewhere, so I wanted to highlight it and maybe hypothesize how it came to be. Any feedback on the flaws, errors, or lack of originality of this idea will be greatly appreciated.

Some context

Long before before Spain and Portugal became rich (and engaged in reckless fiscal profligacy) thanks to New World gold, which became integral to the European gold and silver1 currency trade system, other polities had already enjoyed a golden economic era as key components of the Western Eurasian economic system.

Those polities included the Ghana Empire, the aforementioned Almoravid Empire and the Mali Empire, all of which benefited from controlling the production or trade of West African gold - which accounted for around half of all gold circulating in the Old World - in the centuries before the Age of Discovery.

This was not a minor source of wealth but a major, awe-inspiring one:

[Mali Empire ruler] Musa went on Hajj to Mecca in 1324, traveling with an enormous entourage and a vast supply of gold. En route he spent time in Cairo, where his lavish gift-giving is said to have noticeably affected the value of gold in Egypt…... Contemporary Arabic sources may have been trying to express that Musa had more gold than they thought possible, rather than trying to give an exact number… Musa may have taken as much as 18 tons of gold on his hajj, equal in value to over US$1.397 billion in 2024. Musa himself further promoted the appearance of having vast, inexhaustible wealth by spreading rumors that gold grew like a plant in his kingdom.2

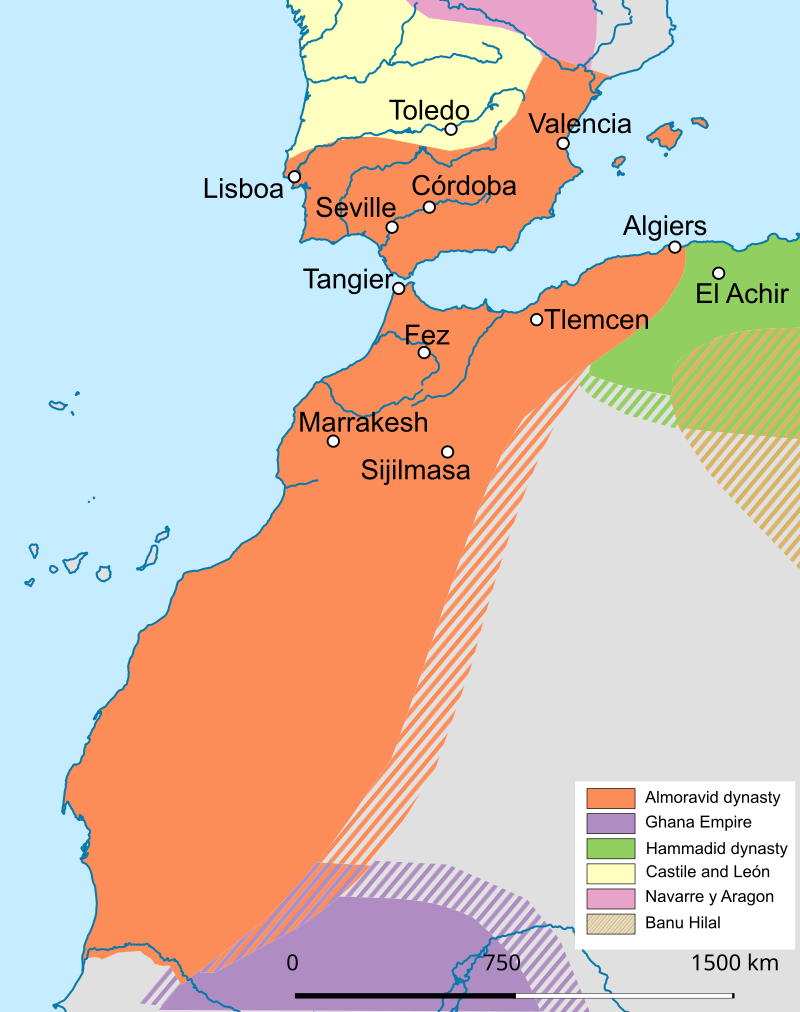

While the Ghana and Mali Empires held sway over vast areas of West Africa south of the Sahara, the Almoravids extended their dominance from their Saharan homeland and the territory of modern day Morocco to encompass a large part of the Iberian Peninsula, following their crossing of the Strait of Gibraltar in 1086.

The Almoravids didn’t cross the Strait of Gibraltar into Europe on a whim. They were invited by the rulers of the weak Muslim kingdoms (Taifas) into which the Caliphate of Cordoba had disintegrated following its 1009-1031 Civil War (also known as Fitna).

And with the Almoravid conquest of Al-Andalus, for the first time, a state had a foothold in Europe, participating in Mediterranean and European trade while simultaneously controlling the routes of the Trans-Saharan gold trade.

The Almoravids proceeded to flood Mediterranean markets with their gold dinars3, at a time when no other European mints were producing gold currency consistently or in significant quantities4.

But before the Almoravid conquest of Spain, and before the Taifas that preceded them, there was the Caliphate of Cordoba.

The Caliphate had held the Christian kingdoms to its north in check by attacking them regularly, pillaging their lands, and thwarting their demographic expansion:

The famous raids, cavalry strikes and aceiphas… had as their tactical and economic objective the taking of captives and cattle from the enemy; strategically they sought to generate a state of permanent insecurity that prevented Christians from developing an organized life outside of castles, fortified cities or their immediate vicinity. Their main feature was the short duration of the campaigns and the remoteness of the points reached by them5.

Under such conditions, it’s hardly surprising that the northern Christian kingdoms struggled to develop trade, expand their cities, and build the state capacity needed to confront their Muslim enemies to the south.

But then the Cordoban Civil War (Fitna) happened.

Elites are a scarce resource

You may have heard that during the time of the Caliphate, Cordoba was the largest city in Europe, overseeing a state that made many contemporary European courts appear primitive by comparison.

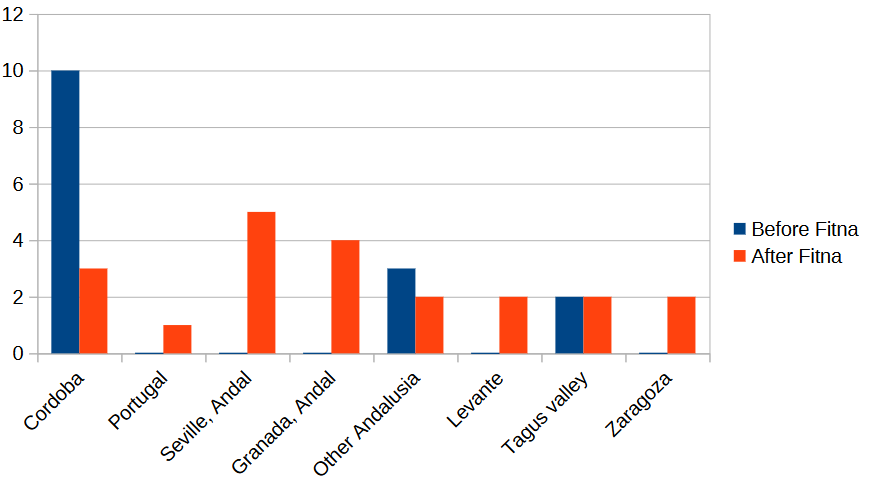

This meant not only a significant concentration of population in Cordoba and its surroundings, but also a very large concentration of Al-Andalus’ elite around the Caliphal court. So very large that two-thirds of all scholars and scientists from al-Andalus6 born before the Fitna, were born in Cordoba or its environs.

How did Cordoba, once known as the Ornament of the World, lost its position as a major European center of learning and declined to become just another big Andalusian city in terms of scientific and scholarly production?

One possible explanation is the slaughter, scattering, and impoverishment of its elite.

Whether Cordoba was partially or completely devastated is uncertain, but what is clear from the numbers of learned men listed as having been killed on the entry of the Berbers into the city in Shawwal 403 A.H. [1013 CE] is that a considerable massacre… did take place…[Cordoba] had suffered three years of siege, had perhaps in part been razed to the ground and its inhabitants evacuated, either by Sulayman b. al-Musta’in or by ‘Ali b. Hammud, or by both. Many of its leading citizens had been killed, either in the battles of Qantish and ‘Aqabat al-Baqar, or in the siege, and many others had been forced to flee in exile. The lists given in the biographical dictionaries of those literati and religious men who left Cordoba in the fitna are impressive7.

In fact, the depletion of al-Andalus’ elite was so severe that Habbus al-Muzaffar, King of the Taifa of Granada - one of the several Muslim kingdoms established after the fall of the Caliphate of Cordoba - had to appoint a Jew - Samuel ibn Naghrillah, himself a refugee from Cordoba - as his Vizier, breaking with the long-standing Muslim tradition against appointing Jewish subjects to positions of power8.

And this decline of Muslim Iberia’s elites was not limited to the scholarly class necessary for managing state affairs, but also appears to have impacted the Taifa kingdoms’ ability to field armies.

The small armies the Taifa kings did gather seem to have been largely directed against fellow Muslims. There was probably an absolute shortage of men as well. We have very few numbers for the armies of Taifa kingdoms, but those we do have seem very small9.

In 1034, when the Taifa King of Seville attempted to revive the tradition of raiding the northern Christian kingdoms, his effort ended in abject failure, forcing him to flee to Lisbon10.

It’s worth noting that the only example Kennedy mentions of a sizeable, well-performing army post-Fitna is from the Taifa of Zaragoza, the only stable Muslim state in northern Spain during the Taifa period11:

The most striking attempt to mobilise Muslim popular opinion came after the fall of Barbastro to the Franks12 in 1064. Al-Muqtadir of Zaragoza was determined to recover the city and his secretary sent out an emotive appeal to his fellow Muslims…Many volunteers appeared from the Marches and even al-Mu’tadid of Seville sent 50 horsemen. There were said to have been 6,000 archers in the Muslim force which retook the city13.

Notice the mention of many volunteers from the Marches, the region controlled by Zaragoza, taking part in this successful military enterprise. This area, mostly coterminous with the modern-day northeastern region of Aragon, was known by the Muslims as the Upper Marches.

This Zaragozan success stands in contrast to the mentions of Muslim civilians not being generally able to participate effectively in military activities (page 281) alongside accounts of the poor combat effectiveness of the Andalusis (page 87).

Was this apparent Muslim Aragonese anomaly related to modern Aragon’s proximity to northeastern Spain, rather than to the southern core of al-Andalus, in terms of current economic and social indicators14?

Almoravid gold

Once the Taifa kingdoms were supplanted by the Almoravid state, the military capabilities of Spanish Muslims increased. However, this new military prowess was largely imported from North Africa, primarily consisting of Berber warriors of the Lamtuna tribe, who had established and then expanded the Almoravid Empire15:

The conquest of al-Andalus by the Lamtuna and their Berber allies was accomplished with surprisingly little violence…To some extent this was the fault of the kings personally. Apart from [a few exceptions] none of them seem to have been either able or determined. Even in his own memoirs, ‘Abd Allah of Granada presents himself as a feeble and incompetent failure, deserted by everyone he relied on, devoured by jealousy of his brother and quite incapable of standing up to outside pressures. None of the rest distinguished themselves…

With the exception of small numbers of slave-soldiers and Andalusi horsemen, the vast majority of Almoravid troops were Berbers, who were typically compensated with spoils from military campaigns and gold dinars minted from Saharan gold (page 171).

In fact, it seems unlikely that the Almoravid state would have been capable of paying regular salaries to its troops or sustain the administrative framework required to finance such payments through taxation:

Apart from the gold, it is not clear that the ‘state’ had any regular income: the tithes (ushur) could be collected, but there is no evidence of a fiscal administration to do this…The Almoravid polity remained, in effect, a conquest state, dependent on new supplies of ghanima (booty) to reward its supporters16.

Even if a lack of state capacity doomed post-Fitna al-Andalus, leading to conquest by its Christian neighbors, it certainly wasn’t the only cause of its fall. As Kennedy notes, demographic decline likely played a significant role in al-Andalus’ downfall.

it does seem clear that at some periods from 1100 onwards, al-Andalus was haemorrhaging people, especially from exposed frontier areas like Cuenca and Beja. There was emigration even from more central areas and we see that old-established families like the Banu Khaldun had largely abandoned Seville in the half-century before the Christian conquest of 1248. The Almohad empire facilitated this as ambitious Andalusis could find employment in Marrakesh or Hafsid Tunis. In the thirteenth century, Andalusi scholars are found in considerable numbers in the Middle East17.

But this hardly explains how a minor Christian kingdom, say Aragon, even if it had access to a considerable pool of high human capital relative to its small population, could confront and defeat a Muslim state whose population was an order of magnitude larger.

And, just as expected, the small Christian kingdom of Aragon was largely unable to capture territory from the Taifa of Zaragoza in the years following the Fitna, except for two small towns18. Even with (potentially) high state capacity, a small kingdom can’t do much.

Coming back to the Almoravids, after they conquered the Taifa kingdoms, they set about reclaiming the territories that the Christian kingdoms had seized from Muslims during the Taifa period. These were primarily conquests made by Alfonso VI of León19 - who also ruled Castile and Galicia - and the most consequential among them was undoubtedly the city of Toledo.

During the Taifa period, Toledo was the capital of one of the major Taifa states, strategically located on the Tagus River, where it dominated the river’s middle valley.

But despite all their efforts, the Almoravids - who succeeded in reclaiming some recently lost lands - failed to capture Toledo. Kennedy believes this was the result of one striking deficiency20:

The Almoravid army was unable to breach the defenses of [Toledo’s] superb natural fortress, and in the end retired. Once again their inability in siege warfare was glaringly apparent.

It appears that despite their wealth in gold, and despite their access to Berber troops with an innate ability for war, the Almoravids lacked a key technical capability. This deficiency consistently placed them at a disadvantage against the Christian kingdoms.

Exit the Almoravids, enter the Almohads

In the 1130s and 1140s, the Almoravid state faced a new and determined enemy, emerging from the High Atlas mountains and centered around another Berber tribe, the Masmuda. The Almohad movement steadily weakened the Almoravids, culminating in their final defeat with the capture of Marrakesh, the Almoravid capital, in 114721.

Many Andalusian cities and territories rebelled against the waning Almoravids, ushering in a second period of fragmented Muslim states known as the second Taifa period22, before eventually submitting to the triumphant Almohads.

The question we should now consider is: once the Almohads took control of al-Andalus, did they revert the apparent shortcomings in state capacity shown by the Almoravids?

Did they put in place a sustainable tax system? Did they wean themselves off Saharan gold? Did they successfully repopulate frontier areas to better defend against Christian advances? Did they enhance Andalusian capabilities in siege warfare?

The answer to all of these questions is: no.

These brief details are interesting because they illustrate one of the main weaknesses of Almohad frontier policy. Towns established on the borders of Christian territory were not viable economically: they had to be sustained by subsidies from elsewhere. It was always difficult in a state with a fairly rudimentary fiscal administration like the Almohads’ to provide regular subventions of this sort and they must have been stopped rapidly in times of civil war or other emergency nearer home23.

The same military failings that plagued Almoravid al-Andalus persisted under Almohad rule.

When the Almohads attempted the siege of even a small town like Huete, the result was a fiasco…What we can say with confidence is that the Muslims of al-Andalus seem to have been unable to take well-fortified and defended cities24.

And fiscal issues kept affecting their capacity to confront Christian armies.

According to ‘Abd al-Wahid al-Marrakushi, writing only a few years after the events, the Almohad troops were paid every four months under al-Mansur, but al-Nasir had been much slower, especially in this campaign, and he had heard of groups of Almohads who had refused to fight at all and had fled at the first opportunity25.

Kennedy emphasizes that Almohad armies prioritized raiding because raiding provided booty to be distributed among their troops, while in contrast, protecting and garrisoning a small, vulnerable Muslim city from Christian conquest did not provide any booty and was not attractive to them (It probably also made the conquest of small, not very wealthy, yet sufficiently fortified Christian localities very unappealing).

Relying on plunder during military campaigns became normalized as a means to compensate for inadequate logistics. Such Almohad deficiencies in logistics could sometimes result in immediate and grave consequence.

on 2 July he ordered that the camp be moved across to the south bank. Despite his efforts, the decision resulted in confusion and the Caliph himself… was left almost alone on the north bank. At this moment the Christian garrison made a sortie and [the Caliph] was mortally wounded, dying a few days later as the defeated and demoralised army made its way back to Seville26.

Eventually, the Almohad Empire resorted to importing new military assets, in the form of Ghuzz Turk recruits from Egypt, who helped to halt the advance of the Christians, but not for long27.

The Almohad state would collapse in the years following its defeat in the battle of Las Navas de Tolosa (1212).

Aragonese musings

As I was finishing reading Kennedy’s book, I kept thinking that I wanted to read more about Northeastern Spain and the medieval political history of this particular region, the Ebro valley, where the Christian Kingdom of Aragon and the Muslim Taifa of Zaragoza faced each other.

As I’ve mentioned before, Zaragoza seems to be, from the little I’ve read, the only post-Fitna Muslim state that mounted a serious resistance against the Christians along its northern frontier. And did this (mostly) without cheating.

And by cheating I mean the practice, commonly employed by the Almoravids and Almohads, of recruiting a majority of their troops from Berber tribes, typically paying them in gold, rather than enlisting from local populations.

The Taifa of Zaragoza did not import soldiers to defend itself, while the Christian Aragonese did cheat. The city of Barbastro was captured by Aragon only with the assistance of French crusaders, and even this unfair victory proved to be ephemeral, as the Aragonese lost Barbastro to the Zaragozans the very next year.

It’s telling that in 1043, a few decades after the Fitna, King Ramiro I of Aragon attacked his Christian neighbor to the west, the Kingdom of Pamplona, but did so in alliance with the Taifa of Zaragoza28. It would seem that the kingdom of Aragon (and probably Pamplona as well) was still significantly weaker militarily than Zaragoza, except when assisted by foreign troops (cheating).

In fact, the Kingdom of Aragon only began to achieve significant conquests at the expense of its natural enemy29 after 1076, when King Sancho Ramírez unified his small Kingdom of Aragon with the similarly small (high human capital?) Kingdom of Pamplona, thereby creating a not-so-small Christian kingdom now capable of fighting Zaragoza effectively.

What am I getting at?

I believe the Fitna (1009-1031) destroyed so much Spanish Muslim human capital that it mostly erased - at least for a few decades - the human capital advantage30 that al-Andalus had previously held over its Christian neighbors to the north.

I think the persistence of the Taifa of Zaragoza as a strong Muslim state in northern Spain during the 11th century was not a historical accident. Instead, it’s likely related to the high level of state capacity shown by the northern Christian kingdoms, in contrast to the southern Taifas and the Almoravid state in the south.

In fact, the Christians only succeeded in conquering Zaragoza and ending the last Muslim state in northern Spain in 1118, eight years after the Almoravids (unwisely?) overthrew the ruling Zaragozan Banu Hud dinasty. As if replacing the local northern Spanish administration with a (predominantly?) Almoravid administration dealt a fatal blow to Zaragoza31.

Caveats

I’ve focused on examining, as thoroughly as possible, the state capacity of Spanish Muslim states after the Civil War of 1009–1031. The case for higher state capacity in al-Andalus compared to the Christian kingdoms in the pre-Fitna period is very compelling, but not very interesting given the large demographic advantage of Muslim Spain.

I know that this post leans heavily on military indicators as a measure of state capacity, while being very light on other aspects (Kennedy’s book is a political history after all). Thing is, people at the time often documented their military achievements (and defeats, albeit to a lesser extent), and so the material available to historians like Kennedy leans towards the military side of history.

Perhaps I’m just abusing the term state capacity. After all, it’s a relatively recent invention (Wikipedia’s state capacity entry was only created in March 2021), and it’s possible I haven’t come across the papers/books that make the same point using other (less fancy?) terms. If that’s the case, I still think this post might be worthwhile just by prodding me to do further research on Aragon/Zaragoza.

I should definitely read more on this subject, particularly about Aragon and the Taifa of Zaragoza.

I hope you’ve enjoyed my musings. I really intended for this post to be shorter, I swear.

In fact, it was mostly a silver-based European trade system before the gold Florin was introduced in the 13th century.

From Quantitative Analysis of Almoravid Dinars. Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient, by Ronald A. Messier (1980): “due to the tremendous quantities in which the dinars were produced, Almoravid currency flooded Mediterranean markets for nearly a century and was a significant rival to Fatimid dinars as the 'dollar' of the Mediterranean“.

The Byzantine Empire, a beacon of state capacity during the European Middle Ages, had continued the minting of gold coins through these dark centuries, though its currency underwent a gradual process of debasement.

The fall of the Caliphate of Cordoba, Peter C Scales, pages 88-89, 101.

Similarly, another exceptional breach of this long-held policy was the appointment of Abu al-Fadl ibn Hasdai as Vizier of the Taifa of Zaragoza (another post-Fitna Muslim kingdom), who was the son of another Cordoban refugee.

Muslim Spain and Portugal: A political history of al-Andalus, Hugh N. Kennedy, page 150.

Muslim Spain and Portugal: A political history of al-Andalus, Hugh N. Kennedy, page 138. Kennedy identifies him as Ismail b. ‘Abbad of Seville, but according to other sources it might have been his son, Abu al-Qasim Muhammad b. Ismail b. Abbad, who ruled the Taifa of Seville from 1023 to 1042.

The small Taifa of Tortosa might also be regarded as part of northern Spain, though it had a short and tumultuous history until its eventual conquest by Zaragoza in 1060.

Kennedy mentions the Franks, because the (first) conquest of Barbastro was the result of a crusade sanctioned by Pope Alexander II. Most crusaders came from France.

Muslim Spain and Portugal: A political history of al-Andalus, Hugh N. Kennedy, page 151.

“Aragon’s GDP represents 3% of Spain’s GDP and its GDP per capita is above that of Spain [also, HDI is sixth highest in Spain] and with a not very large gap with respect to that of the European Union“.

Muslim Spain and Portugal: A political history of al-Andalus, Hugh N. Kennedy, page 161.

Muslim Spain and Portugal: A political history of al-Andalus, Hugh N. Kennedy, page 161.

Muslim Spain and Portugal: A political history of al-Andalus, Hugh N. Kennedy, page 305.

The towns of Litera and Benabarre in 1062.

Primarily, though not exclusively. I’ll discuss the minor conquests of the Kingdom of Aragon, and the specific circumstances surrounding them, in just a moment.

Muslim Spain and Portugal: A political history of al-Andalus, Hugh N. Kennedy, page 173.

It’s noteworthy that an important component of the Almoravid army that confronting the Almohads in Morocco was comprised of former Christian prisoners who had been engaded as mercenaries under the command of the Catalan, Reverter de La Guardia. Reverter reportedly rose to lead the Almoravid forces, and only three years after his death in 1144 the Almoravids suffered a decisive defeat that led to their replacement by the Almohads as rulers of Morocco and, ultimately, al-Andalus.

1144-1147.

Muslim Spain and Portugal: A political history of al-Andalus, Hugh N. Kennedy, page 260.

Muslim Spain and Portugal: A political history of al-Andalus, Hugh N. Kennedy, page 307.

Muslim Spain and Portugal: A political history of al-Andalus, Hugh N. Kennedy, page 272.

Muslim Spain and Portugal: A political history of al-Andalus, Hugh N. Kennedy, page 236.

Kennedy mentions that after the Navas de Tolosa battle in 2012, which marked the beggining of the end for the Almohads in Spain, there is no more mention of the Ghuzz (page 283).

reyesmedievales.esy.es, “Ramiro I Rey de Aragón (h.1020<1035-1063>1063)“.

By ‘natural enemy’ I mean the Muslim state directly to its south. while Christian kingdoms fought against each other from time to time, as numerous border changes attest, in the context of the Reconquista, each Christian kingdom naturally aimed to expand towards the Muslim lands to its south. For Aragon, this meant that any southward expansion depended on defeating Zaragoza.

Largely demographic based.

I’m far from a 100% certain about this point. See my caveats below.

Informative and interesting article--and in my opinion *not* too long...

'In fact, the depletion of al-Andalus’ elite was so severe that Habbus al-Muzaffar, King of the Taifa of Granada - one of the several Muslim kingdoms established after the fall of the Caliphate of Cordoba - had to appoint a Jew - Samuel ibn Naghrillah, himself a refugee from Cordoba - as his Vizier, breaking with the long-standing Muslim tradition against appointing Jewish subjects to positions of power'

This is one interpretation. Couldn't it also have been that the Jews had rendered exceptional assistance to the king, as they had previously rendered an exceptional disservice to the Visigoths in opening the gates of Toledo to the Muslims a few hundred years before?

I have doubts about the degree to which HHC was wielded by the Iberian Muslims themselves. Dario Fernandez-Morera's book Myth of the Andalusian Paradise argues that Muslim achievements in science, engineering, literature etc are overstated and that they depended heavily on native Spanish (and Jewish) brains in the service of Muslim lords. By your reckoning this too would be a form of 'cheating'.

I don't fully understand what explanation you are proposing for Zaragoza's superior position relative to the other post-Taifa Muslim states. I take you to mean it was because of 'cheating'--proximity to the HHC Christian Aragonese--rather than the HHC the Muslim Zaragozans themseves possessed. Or have I misunderstood?

NB: By no means do I pretend to any great learning on this subject; but I am interested in it.

Interesting. However I'm disturbed by you placing the "fitna" (never read that term before except for the Shia-Sunni split) or the collapse of the Cordoba Caliphate a century before it actually happened. A simple excursion to Wikipedia will tell you that it collapsed ***in 1031*** and not 929, when the Caliphate did not even exist yet (it was the "independent Emirate"). 929 is when the Emirate becomes Caliphate under Abd al-Rahman III (Abderramán III in Spanish). That's a major error.

Ab al-Rahman was incidentally the most Basque Caliph ever: lots of his matrilineal ancestors were Basque (when I was in FB we estimated that he was well above 90% Basque by ancestry, even if also Arab by strict patrilineage). This reflects the policy of Cordoba Ummayad alliances with Pamplona (later called Navarre), which was around 1000 CE the most powerful Christian state in Iberia. Sancho III the Great was also Count of Castile by marriage (formerly part of León), Aragon (which was part of Pamplona Kingdom as such), Sobrarbe and Ribagorza (formerly part of the Spanish Marche of the Franks). He also became overlord of the Duchy of Gascony (previously under West Francia, alias France) and occupied militarily much of León (but not Galicia, which supported a rival claimant to the Leonese throne). He was even called "imperator hispaniae" (Emperor of the Spains) by bootlicking chroniclers (who also pompously compared Pamplona to ancient Rome).

Pamplona went into "fitna" almost synchronously with the Cordoba Caliphate, in 1035. Sancho's "empire" was divided among his four sons: García, the elder, became King of Pamplona, Ferdinand, the second-born, had already been appointed as Count of Castile, the third legitimate son, Gonzalo became Count of Ribagorza and Sobrarbe and the bastard Ramiro became Count of Aragon (Jaca district), directly under Pamplonese sovereignty. The partition did not last: Gonzalo died soon afterwards (date is unclear but could have been as early as 1035, before 1040 in any case) and Ramiro took over the Pyrenean counties. Then Ferdinand defeated and killed him at Atapuerca (then the border between Pamplona and Castile, just NE of Burgos) in 1054. Pamplona lingered some decades more but it was finally partitioned between Castile (which got most of the Western Basque Country and La Rioja) and Aragon, which got what would be later called Navarre.

It would be under the line of Ramiro, especially with Alfonso the Battler (1104-34), when Navarre re-expanded westwards (and also southwards to Tudela), but Aragon got the best prize: Zaragoza, via a regional crusade backed by many Occitan lords. He died heirless and wanted to donate the whole realm to the Templars but his will was overriden by the separate cortes (parliaments) of Navarre and Aragon and two different relatives were elected as kings instead. Later on, in a short treacherous war waged by Castile in 1199-1200, the Western Basque Country was conquered by these. However, as the previous conquest had caused many uprisings, this time especial autonomous status was given to the three provinces (Alaba and Biscay existed previously as Navarrese counties, Gipuzkoa was founded then), which allowed the Navarrese legal code and democratic self-rule to persist until today in some limited aspects or until the 1830s or 1870s (Carlist Wars) in others.

My understanding is that Castile, especially after the conquest of León (and independence of Portugal, related events) had become so massively powerful that it just went on rampage: first forcing the abdication of their own vassal, the Emir of Toledo (who was placed as Emir of Valencia), then against Navarre and finally against the Berber jihadists, which could only do so much in the long term. Aragon also became even stronger as it went to the House of Barcelona when Alfonso the Battler's niece Petronila married Ramón Berenguer IV. Both Aragon-Catalonia and Portugal then operated pretty much as the sidekicks of Castile-León and they were unstoppable. The rest, as they say, is History.