How the Amish spend their time

On fertility, and outsourcing to your community the enforcement of trade-offs in time allocation.

In my previous post I presented a highly speculative hypothesis proposing that the widespread adoption of television and radio might be one of the causes of the decline in fertility rates experienced by many countries during the 20th century.

I'll now attempt to clarify this hypothesis by presenting the case of a population that has not adopted television or radio, even though they live surrounded by people who have.

The Amish are a group of traditionalist Anabaptist Christian church fellowships with Swiss and Alsatian origins.

As they maintain a degree of separation from surrounding populations, and hold their faith in common, the Amish have been described by certain scholars as an ethnoreligious group, combining features of an ethnicity and a Christian denomination.1

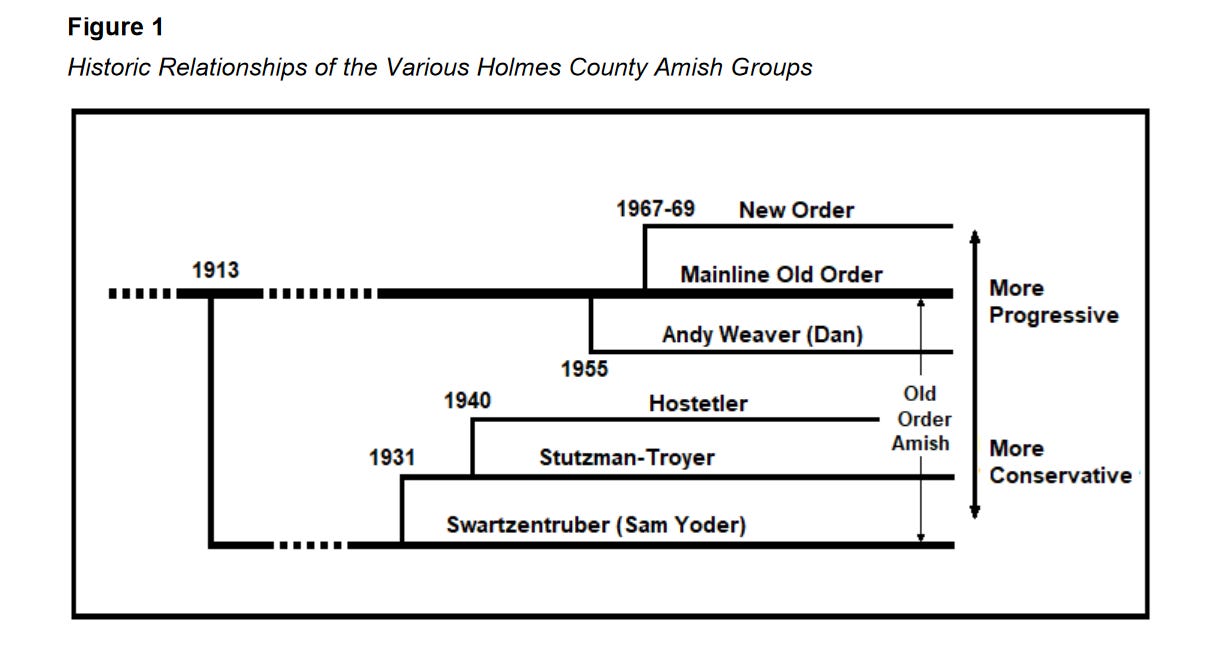

Over the course of more than two centuries since their arrival in Pennsylvania, the Amish community has experienced numerous schisms that have led to the formation of many diverse affiliations. Each of these affiliations adheres to a common Anabaptist doctrine and maintains a similar lifestyle, but they differ in certain theological beliefs and community practices, particularly in regards to the allowance or prohibition of some modern technologies.

My interest in them, at least for the purposes of this post2, rests in that they don’t watch television or listen to the radio. In fact, for the most part3, they don’t use any electrical appliances that require alternating current from an electrical grid.

If you are familiar with the Amish, you probably know about their high fertility rate and may have already read about some of the most commonly cited explanations for this high fertility.

Those explanations will likely be similar to the ones I compiled from a Reddit thread on this topic: lack of birth control, boredom, religious mandates or precepts, and lack of women’s rights.

If you’ve read my previous post, you are likely aware that I favor the “Amish don’t have TV so they’ve got to spend their time doing something“ explanation. I will now present and analyze what I believe to be strong evidence supporting that explanation.

For the purposes of the analysis I’m presenting here, it’s fortunate that various Amish affiliations have different rules regarding the use of modern technology and appliances, some being more conservative than others. In fact, many historical splits in the community have been the result of disagreements about adopting new technologies.

There’s little difference in terms of actual religious practice or doctrine between different Amish groups. In the context of Amish studies, when a group is described as more conservative this means it’s less inclined to adopt new technologies and devices and less open to the outside world.

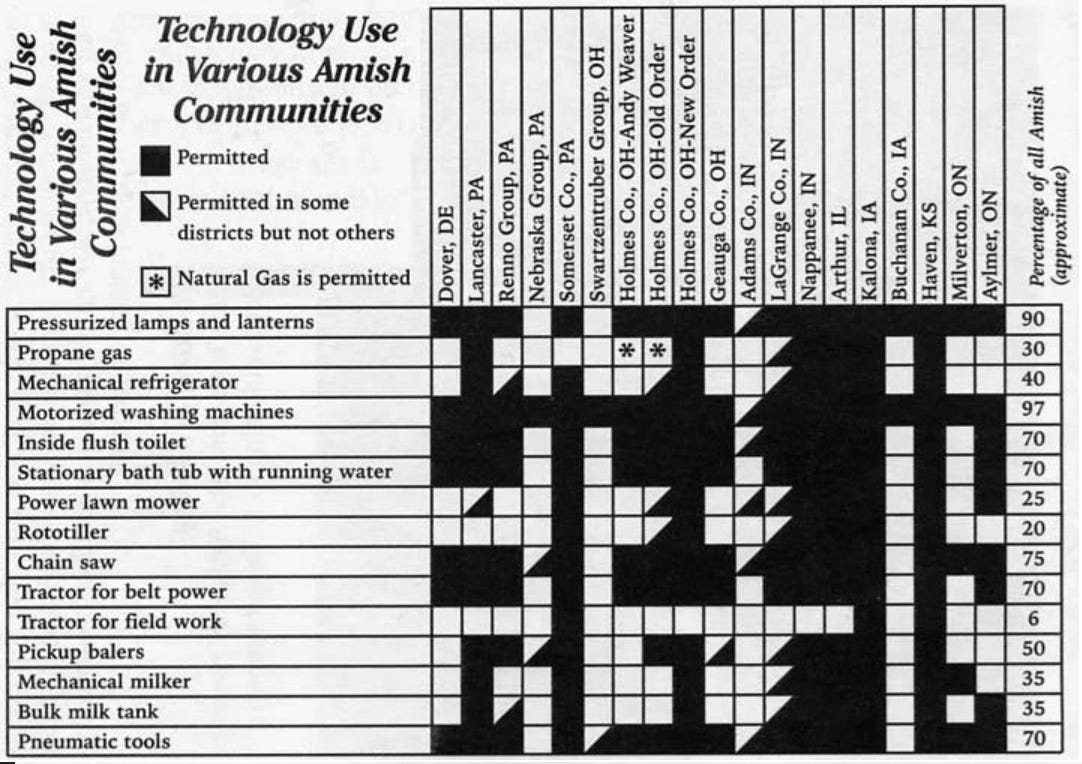

The following table provides an overview of the technologies allowed by several (most?) Amish groups.4

You’ll notice that radio and television are not mentioned among the technologies in the previous table. In fact, no Amish group allows their use. But there are differences in the permissibility of the use of some electronic devices such as fixed phones (Beachy and some New Order allow them), computers (mostly for businesses by non-farming Amish), and smartphones (it’s complicated).

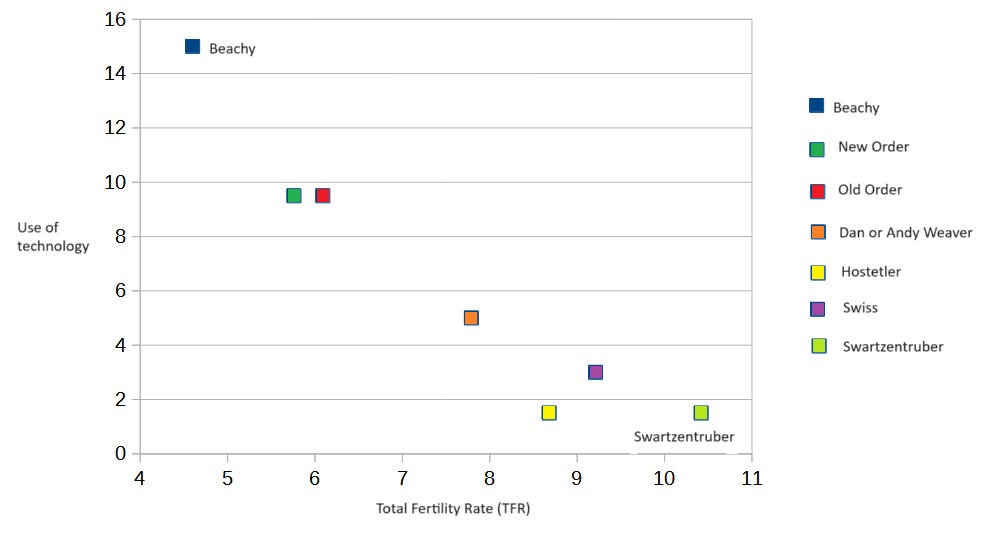

By combining the technology use data with the fertility rates for some of these groups5, which I obtained from a 2022 paper by Henry Troyer6, I can generate a chart plotting these two variables:7

Notice how even the least “conservative” affiliation, the Beachy Amish, have a TFR significantly higher than the American average, at approximately 4.6 children per woman.

The chart shows a clear correlation between how “conservative“ a group is and its fertility rate. The more restrictive the affiliation, the higher its TFR.

The extent of “conservatism” within an Amish affiliation is also related to the use of other modern conveniences such as cars, with only the most “liberal” group, the Beachy Amish, allowing car ownership.

You might think of a car as a time-saving technological device. A quick means of reaching destinations that would otherwise take significantly longer to reach. But from another point of view, not having a car means freeing all the time that you would potentially spend in superfluous (or at least non-essential) pursuits that require a vehicle, while allowing for more time to be dedicated to work and family life.

When your life seems to be filled with activities that rely on modern technology, it can be hard to give up long-acquired habits in order to make time for a newborn child. At least harder than the Amish alternative of not filling up your life with activities that require the use of modern technology and devices.

At first glance, this reasoning might seem to present some inconsistency with the restrictions that Amish communities impose upon themselves. Why not use tractors and mechanical milkers8 to save time that could then be spent with family?

I don’t think this presents a major inconsistency. Notice that, out of all the technologies listed in Scott and Pellman’s table, the only one that is almost universally allowed9 by all affiliations is the motorized washing machine. This seems very consistent with a preference for large families while acknowledging how demanding it is to wash the resulting heaps of children’s clothes.

The Amish not only have a preference for spending their time raising children, and I assume, enjoying the process, but have also managed to outsource the enforcement of the community rules necessary to maintain their preference.

What about confounding factors?

Of all the other factors proposed as a possible explanation for Amish high fertility, the supposed biblical injunction to have many children might initially appear as a plausible explanation for their high birth rate. The Amish are certainly very religious.

That would explain their high fertility compared to the general population, but does it explain the differences in fertility between Amish groups?

It’s hard to decide which Amish groups are more religious than others. This quote from Wikipedia highlights some of the challenges in categorizing Amish groups as either more 'conservative' or more 'liberal':10

[The New Order Tobe] share an unusual mix of conservative and progressive traits…In only 50 years there were four splits, the first from the mainstream forming an extremely conservative group and then three splits in a more liberal direction.

All Amish adhere to a common Anabaptist doctrine, defined by the Schleitheim Confession, and their religiosity appears to vary more in terms of practices than in fundamental beliefs.

On the other hand, there is a wide spectrum of technologies permitted and prohibited by different Amish groups, which allows us to establish a fairly consistent level of conservatism for each group, where more conservatism means more restrictions on modern technologies.

What if we define religiosity in terms of practices? Some Amish groups engage in evangelical practices such as mission work, while others do not. Some groups have Sunday schools, meetinghouses for worship service or strict bans (excommunications), while others do not.

If we consider a more evangelical outlook as more religious, then the Beachy and New Order Amish, the most “liberal” of the seven groups mentioned earlier, are the most religious in that regard, as they engage in missionary work even outside the United States.

If religiousness is measured by the frequency of community worship, then once again, the Beachy Amish are the most religious, as they worship every Sunday, whereas most groups worship every other Sunday

Is Bible study a good indicator of the religious commitment and engagement of a community? Most Amish seem to engage in informal Bible study, but only the more “liberal” Beachy and New Order set up Sunday Schools.

The only religious practice where more technologically restrictive Amish groups appear to be more religious is in the strict application of excommunications or bans. The more technologically restrictive groups, such as the Swiss Amish, tend to practice a more stringent form of banning.

Personally, I am inclined to view the excommunication of members from a religious community more as a social practice rather than a religious one.

Considering the adoption or avoidance of these religious practices by the Amish, It seems very dubious to me that a positive correlation between the religiosity of various Amish affiliations and their fertility exists. In fact, I think the opposite is more likely.

And why owning a car lead one to hell, whereas it is perfectly permissible to ride in one? These riddles of Amish life appear silly and downright ridiculous to many Moderns.11

What may seem like a riddle at first sight can be explained by assuming the Amish have clear time preferences, and rules for defining what is essential and what is superfluous, that derive from those preferences.

In my next post on this topic, I intend to go back to Latin America12 and examine how this proposed effect of time allocation on fertility may not always derive from preferences.

As a non-American, my prior knowledge of the Amish was primarily derived from American media and online articles, such as the Wikipedia entry I just cited. There are no Amish communities in any of the places I’ve lived.

Please do not misunderstand me. The Amish are a very interesting people.

There’s one Amish affiliation which allows the use of electrical appliances.

Estimating fertility rates for certain groups can be challenging due to the lack of surveys or genealogies.

TFR for the Swiss Amish (Michigan) from Donnermeyer 2023 (birth cohort 1969-1973). TFR for the Beachy Amish estimated from the rate of increase of their population. Hostetler Amish assumed to have the same use of technology as the Swartzentruber Amish. To calculate the Use of technology value for each affiliation, I assigned 1 point for each allowed technology and 0.5 points for each technology allowed in some districts.

Milk production is a common occupation among Amish farmers.

Except by the Swiss Amish in some districts.

From Donald B. Kraybill (2001), The Riddle of Amish Culture.

I was tempted to write about Latin American Mennonites in this post, but I’ll leave that for a future piece.