1962 in Chile: Of Football, TV and fertility

A natural experiment in fertility. Sort of.

The year 1962 was a pretty important year in Chilean history. Although it did not witness any major political upheaval, such as elections, coups, or revolutions, nor was it marked by any natural disaster1, this year holds a special place in the hearts of the football-loving (soccer-crazy) South American nation. This was the year Chile hosted the FIFA World Cup in 1962, a momentous event that remains etched in the nation's collective memory. Not only did Chile host the tournament, but its national team also achieved an unprecedented feat, securing third place - the highest position ever attained by a Chilean squad in a World Cup to this day.

Two years previously Chile had experienced the 1960 Valdivia earthquake, which claimed between 1,000 and 6,000 lives and inflicted damages estimated at between US$400 million and US$800 million, devastating southern Chile.

Lacking enough time to repair or rebuild the damaged venues, the organizing committee was compelled to opt for smaller stadiums2 to host a minimum of four venues. With a population of 8 million at the time, most Chileans would have been unable to watch the matches live had it not been for a new emerging technology that was just beginning to take its first steps.

The magic of Television

The late 1950s saw the introduction of television in Chile on an experimental basis. Television licenses were only granted to universities3, which primarily used the medium for educational content, and consequently the number of television sets in the country remained low, with estimates ranging between 3,000 and 5,000 before 19624.

The World Cup catalyzed a significant transformation in Chilean television. Broadcasters invested in new equipment to enable the live broadcast of matches, which led to more varied programming and stimulated a surge in demand for television sets.

There were a lot of television sets in public places. For example, stores would put a TV in their windows and people would come. It's not that the State put television sets in the streets. The other thing was that the 'poor person' who had a TV in a neighborhood would have his living room filled with neighbors coming to watch the game.5

By the year's end, the demand created by World Cup fever, coupled with reduced import restrictions and the opening of a local factory to supply the local market, resulted in a significant increase in the number of television sets, surpassing 20,000.

People not only bought TV sets in unprecedented numbers, but also radios:

There were a lot of portable radios, small, battery-powered, many people took them to the stadium to listen to the story of the game. Since it was a World Cup, many people joined who had never seen football, so it was good to hear the story in your ear to identify the players.6

Television changed the social life of Chileans, just like it changed the lives of most people around the world.

But it was not the only change that Chilean society was experiencing at the time.

The world's best babysitter

The 1960s were a period of significant social change, particularly in the Western world, marked by the women's liberation movement and the introduction of the birth control pill:

In the decade after the Pill was released, the oral contraceptive gave women highly effective control over their fertility. By 1960, the baby boom was taking its toll. Mothers who had four children by the time they were 25 still faced another 15 to 20 fertile years ahead of them. Growing families were hemmed into small houses, cramped by rising costs.

As the 1960s progressed, the women's liberation movement gained momentum…With almost 100% fertility control, women were able to postpone having children or space births7 to pursue a career or a degree that had never been possible prior to the Pill.8

It seems to be common knowledge9 that the introduction and popularization of the birth control pill lowered fertility. But common knowledge is not always true.

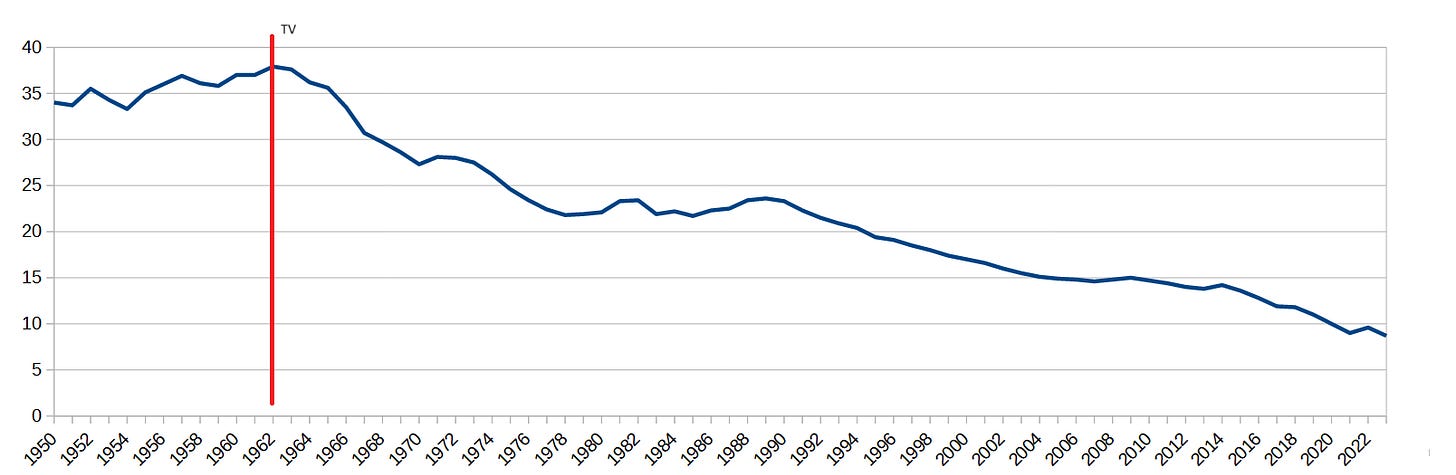

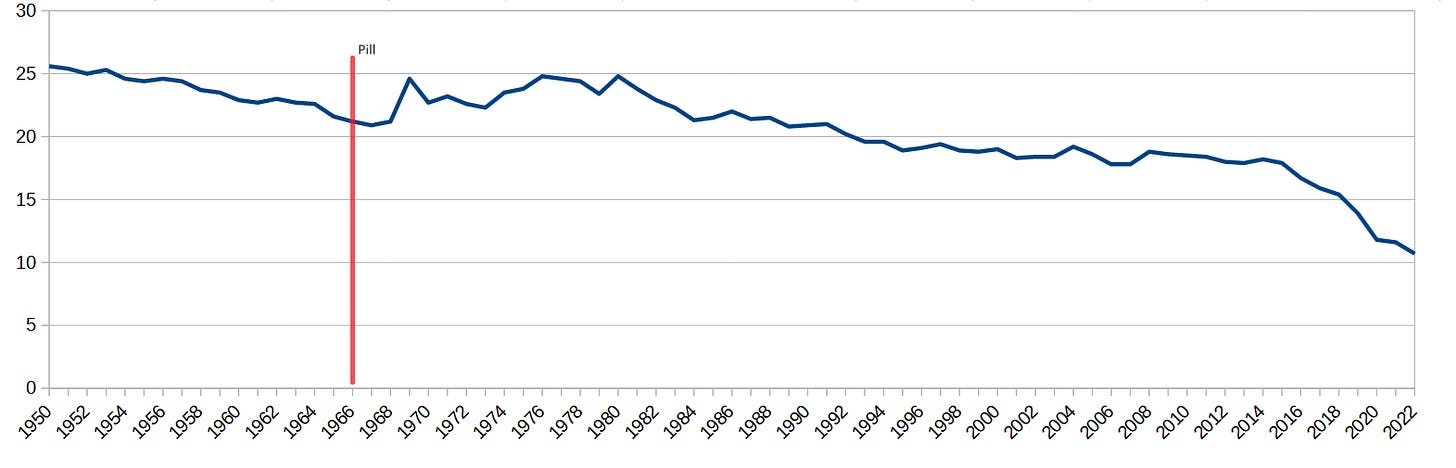

Let's examine the trends in Chilean fertility10 (crude birth rate) over the past 70 years:

It's quite the coincidence how the widespread adoption of television in Chile seems to precede the decline in fertility rates. But coincidences do not imply causation.

Several confounding factors could have driven the decrease in fertility, such as increasing urbanization, rising levels of female education, and the aforementioned birth control pill.

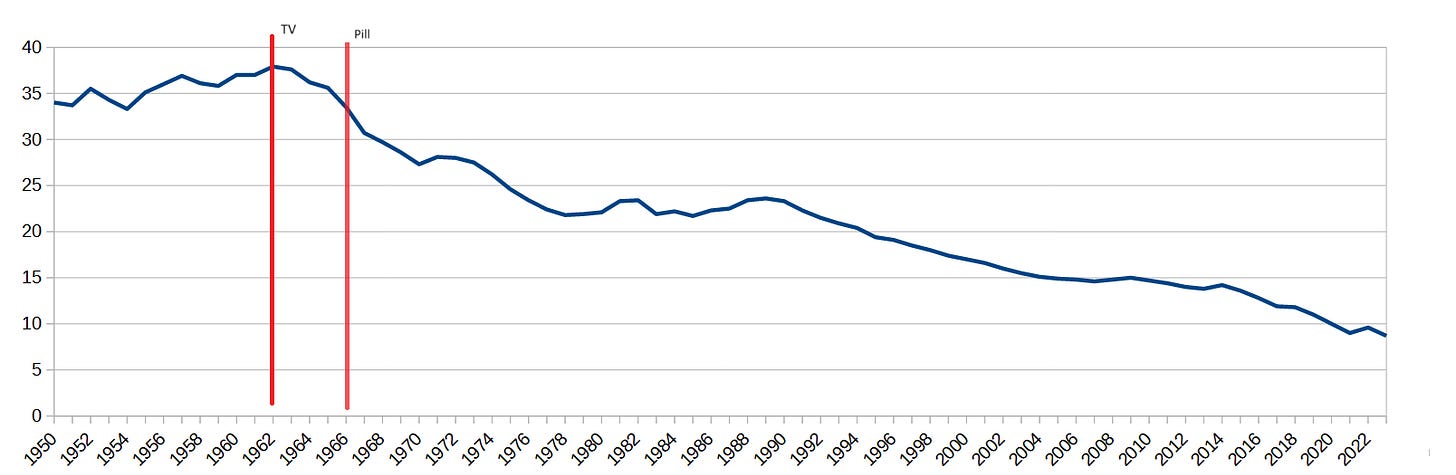

However, there’s a problem with attributing the decrease to the birth control pill. The pill was not widely introduced in most of Latin America until the late 1960s, rather than the early 1960s:

An example of this type of global outreach campaign is the animated film Family Planning, released in 1967 and produced by the population council and Walt Disney. Since 1940 Walt Disney had been developing materials for political purposes in partnership with the US government. This film, which was translated into twenty-three languages and widely distributed in Asia and Latin America, showed the serious problems associated with the lack of family planning…

Starting in the mid-1960s, associations affiliated with the IPPF [International Planned Parenthood Federation] were created in various countries of the region, sometimes with the support of local governments and international organizations and associations. The goal of these associations was to promote family planning. They included Association for the well-being of Colombian families, Sociedade Civil Bem-Estar Familiar no Brasil, and the Association for the well-being of Ecuadorian families, both for [sic] founded in 1965; the Chilean association for family protection, the Costa Rican demographic association and the Family protection association of Argentina, founded in 1966; the Family protection association of Peru and the Family planning foundation of Mexico, founded in 1967; and the Family planning association of Uruguay, established in 1968.11

Updating the previous fertility chart to include the introduction of the pill, we can see that decreasing fertility predates the pill:

It’s also worth noting the effect that Pope Paul VI encyclical Humanae Vitae, which rejected unnatural contraceptive methods, might have had in the very catholic countries of Latin America. The encyclical was published in 1968, concurrently with the efforts to disseminate the use of the pill, and likely delayed its widespread adoption and any possible effects on fertility of that adoption.

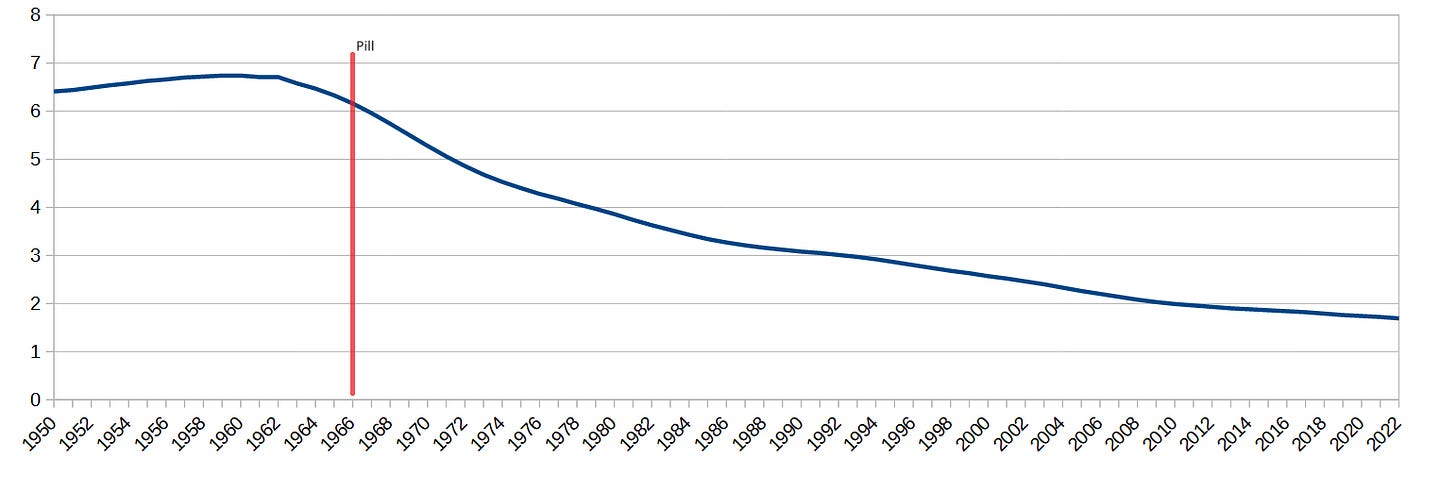

And it’s not just Chilean fertility that doesn’t fit with the idea that the birth control pill started the trend to lower fertility in Latin America. Here’s the chart for Colombia:

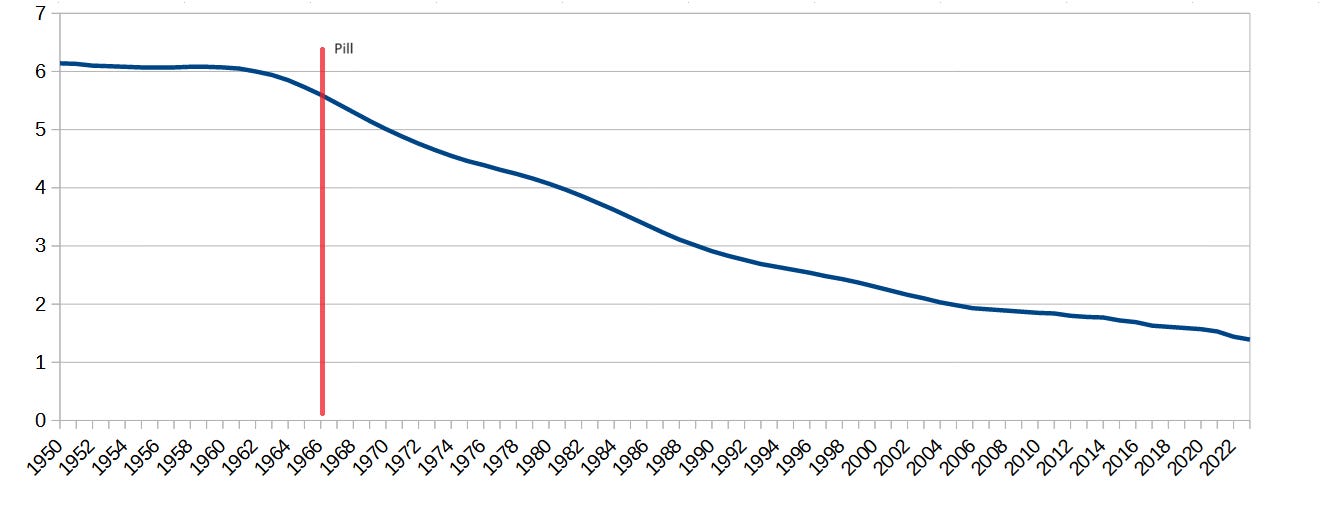

And here’s Brazil:

And here’s Argentina12:

I’m not going to address whether increasing urbanization and rising levels of female education are better explanations for declining fertility in this post, as I believe their causal mechanisms for lowering fertility are mostly the same as those of television adoption.

The American case

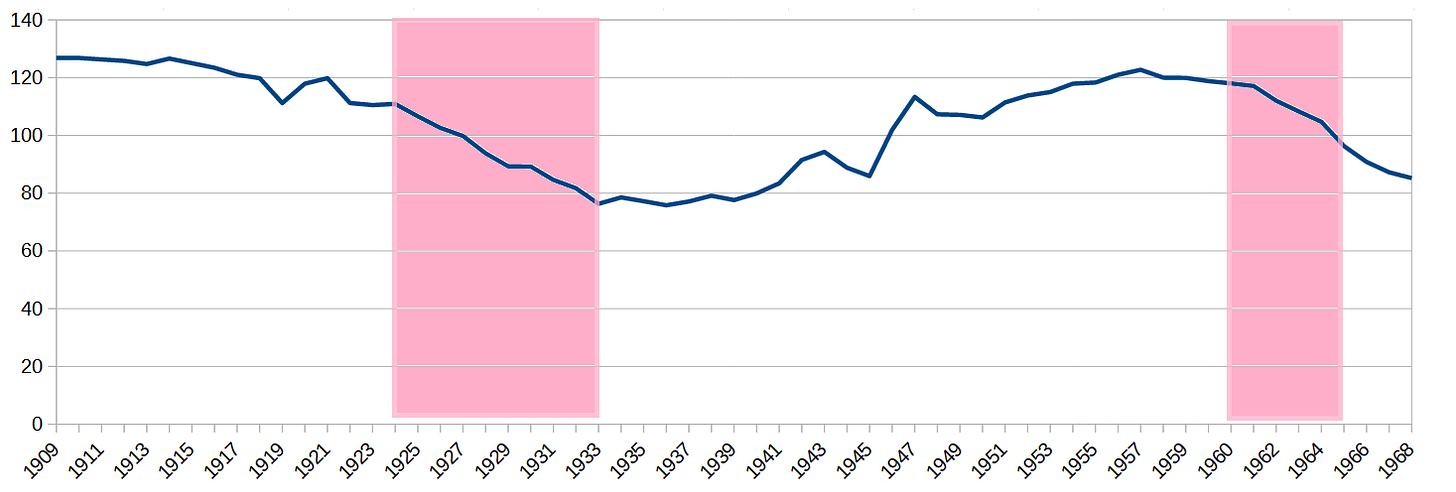

Before presenting a similar chart for the United States, I must acknowledge that based on the graph alone, the case for television having a significant impact on fertility rates is not particularly compelling. So, I decided to cheat and also mark the introduction of the radio in the chart.

Although fertility rates in the U.S. had already begun declining before the 1920s, it was during the latter half of that decade, when the radio sees widespread adoption13, that they started to decrease at a much faster rate.

The idea that the advent of television (or radio), along with the accompanying changes in social norms, contributed to decreased fertility is purely speculative on my part. But I felt compelled to propose this theory, if only to underscore how flimsy the case is for attributing the 1960s reduction of fertility to the introduction of the birth control pill.

Certainly, the experiences of Chile and other South American countries during the first years of television broadcasting are far from the best natural experiment I could wish for in order to determine whether time-intensive entertainment influences fertility rates. Nevertheless, they provide a useful starting point for arguing this theory, and I do hope to present some more pertinent data in future posts.

Though two years prior the 1960 Valdivia earthquake, the most powerful earthquake ever recorded, affected southern Chile, claiming between 1,000 and 6,000 lives and inflicted damages estimated between US$400 million and US$800 million.

Until the 1990s most Chilean TV broadcasters were affiliated with universities.

See “‘Un quiebre social’: a 60 años, el impacto del Mundial de Fútbol en Chile“, https://www.latercera.com/que-pasa/noticia/un-quiebre-social-a-60-anos-el-impacto-del-mundial-de-futbol-en-chile/SODUZKUSXBBEVMACAWEFDIMUDM/

See “Por radio, por TV y en tiendas: ¿cómo Chile siguió el Mundial de 1962?“, https://www.latercera.com/culto/2022/05/30/por-radio-por-tv-y-en-tiendas-como-chile-siguio-el-mundial-de-1962/

See “Por radio, por TV y en tiendas: ¿cómo Chile siguió el Mundial de 1962?“, https://www.latercera.com/culto/2022/05/30/por-radio-por-tv-y-en-tiendas-como-chile-siguio-el-mundial-de-1962/#

I probably don’t need to remind my readers that this statement is false. Women had been postponing having children and spacing births for centuries before the advent of the birth control pill.

“The Pill and the Women's Liberation Movement“, PBS American Experience, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/pill-and-womens-liberation-movement/

There’s also an academic literature on the effects of the birth control pill, including a minor effect on delayed marriage and consequently in lower fertility: “The estimates in column 1 indicate that the adoption of a nonrestrictive birth control law for minors was associated with a modest (but statistically significant) two-percentage-point decline in the probability that a college graduate women was married before age 23“. Goldin and Katz 2002, “The Power of the Pill: Oral Contraceptives and Women's Career and Marriage Decisions“, https://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/2624453/Goldin_PowerPill.pdf

Although TFR is a more accurate indicator, I couldn’t find data for TFR before the year 1990.

See Felitti 2022, “The Birth Control Pill and Family Planning“, https://oxfordre.com/latinamericanhistory/display/10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.001.0001/acrefore-9780199366439-e-1043

No, I’m not suggesting the introduction of television in Argentina (it became widespread in the early 1960s) increased fertility in Argentina. I will discuss that 1970s and 1980s bump in Argentina's fertility in a later post, but in the meantime let me clarify that the hypothesis I’m proposing is not about TV having a significant direct effect on fertility. Television is just one element among many within a broader category.