Georgia's successful (?) campaign to increase birth rates

Well, not really a campaign... and not the Georgia you might be thinking of...

If you’ve been following the online discussions and debates about the global decline in fertility rates, prompted by fertility rates below replacement level in nearly all high-income and many middle-income countries, then you’ve probably come across various explanations for this phenomenon.

In fact, I’ve written about this topic before, offering my own opinion on this matter based on the data I’ve analyzed:

Many of these proposed explanations directly lead to proposed solutions - assuming low fertility is a problem to be solved. For instance, the hypothesized effect of microplastics on male infertility, coupled with attributing low birth rates to reduced male fertility, might logically lead one to propose a ban on the kinds of plastics that degrade into microplastics.

In this post, I want to focus on a proposed solution to declining fertility rates, based on the experience of a small middle-income country that apparently reversed its falling Total Fertility Rate (TFR)1 through an unorthodox approach.

The country in question is very much Orthodox though. It’s the country of Georgia.

The basic fact that Georgia significantly increased its TFR from 2007 to 2018, eventually surpassing the replacement level2, is incontrovertible. Before that time period, like many other former Soviet republics, Georgia’s TFR was in the range of 1.5 to 1.6 children per woman.

The usual narrative explaining this remarkable increase in fertility goes like this:

In late 2007, worried about Georgia’s low fertility rate and its implications for the nation future, Patriarch Ilia II (Georgian: ილია II3), the head of Georgia’s Orthodox Church, announced he would personally baptize any child born to families with at least two previous children. As a consequence of this announcement, coupled with the Church’s broader promotion of childbirth, birth rates increased.

He conducts mass baptism ceremonies four times a year. The patriarch’s initiative contributed to a national baby boom, as being baptized by the Patriarch is a considerable honour among adherents of the Georgian Orthodox Church.

Given Georgia’s strong religiosity4 and the widespread popularity of Patriarch Ilia, it’s plausible to assume his campaign to raise fertility succeeded.

And both social media and the BBC agree that this was the case:

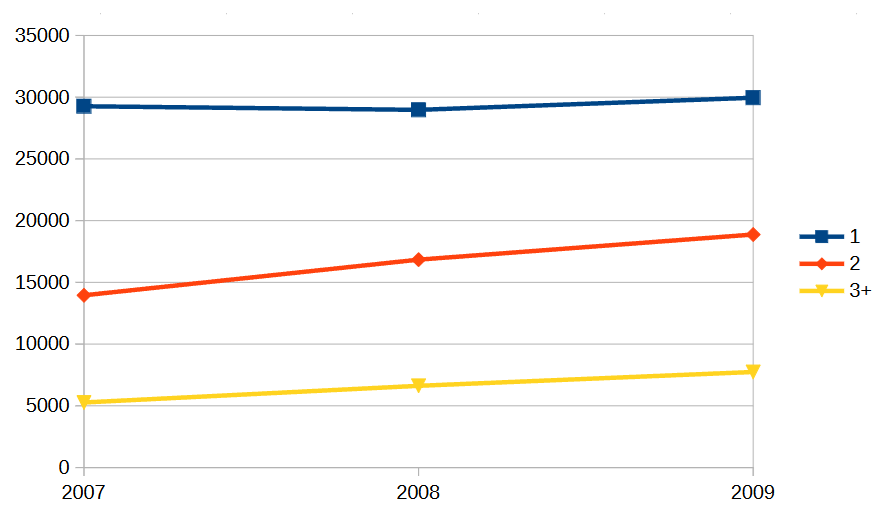

In fact, the increase in births seems to be concentrated among third or higher-order births, precisely as one might expect following the Patriarch’s offer:

This gives credence to the argument that top-down policies can effectively raise fertility rates by nudging or shifting cultural norms towards having more children.

For a more comprehensive and thorough account of Georgia’s story of a religiously inspired fertility boom, I recommend reading this report report by demographer Lyman Stone:

Can a popular social figure alter birth rates by bestowing special honors on high-birth-order children?…As you can see from the figure above, there’s a sharp spike in births in 2008. News reports and politicians at the time attributed this rise to the patriarch’s pro-fertility, anti-abortion campaign.

The numbers

So, that is one (the?) narrative of Georgia’s rising fertility5.

Since we have access to comprehensive data on Georgian births by year, region, and birth order, we can thoroughly analyze the data, exploring it from every angle6 .

First, let’s check the increase in births from 2007 (the year when Patriarch Ilia II did his announcement) to 2009:

Third-order and higher births (3+) increased substantially, yet second-order births also rose, which was not an expected outcome of the Patriarch’s mass baptism campaign. Admittedly, third-order and higher births increased by an impressive 47%, compared to an increase of only 35% in second-order births7.

Let me now expand the dataset to include the years 20058 and 2006, presenting all figures relative to the 2005 baseline:

The gap between the increase in second-order and 3+ births has narrowed (38% vs 44%), and more importantly, there’s clear evidence that the rise in second-order and higher births was preceded by a substantial (8%) increase in first-order births between 2005 and 2007.

Even though an increase in first-order births does expand the pool of potential mothers for second-order babies, I wouldn’t say that this definitively proves that the raise in second-order births (2007-2009) was solely a consequence of the previous raise in first-order births (2005-2007), or correspondingly the raise in 3+ births was simply a consequence of the raise in second-order births.

It’s difficult to determine whether third-order and higher births were motivated by religiousness. I made a rough estimate of the share of 3+ births for which the parents undertook the one action that suggests a religious motivation: taking their baby to Patriarch Ilia for baptism.

Judging by the figures reported by the Georgian Orthodox Church9, that share of third-order and higher babies who were actually baptized ranges between 28% and 38%.

If the proportion of baptized babies were close to 0%, I would be highly confident that religiosity is not the cause of the increase in births. Conversely, if the proportion were close to 100%, that would be a very strong argument for religiosity as a cause of the increase.

But the actual figure is not low enough nor high enough to conclusively assert anything.

Muslim baptisms and wrong patriarchs

Being situated in the Caucasus, at the crossroads between Europe and Asia, linking the Muslim and Christian worlds, it is no surprise that Georgia is not a homogeneous country.

Luckily, that heterogeneity offers an excellent opportunity to test the effect of the Orthodox Church’s campaing, or lack thereof, on populations experiencing the same economic and social conditions as Orthodox Georgians, but who follow a different religion.

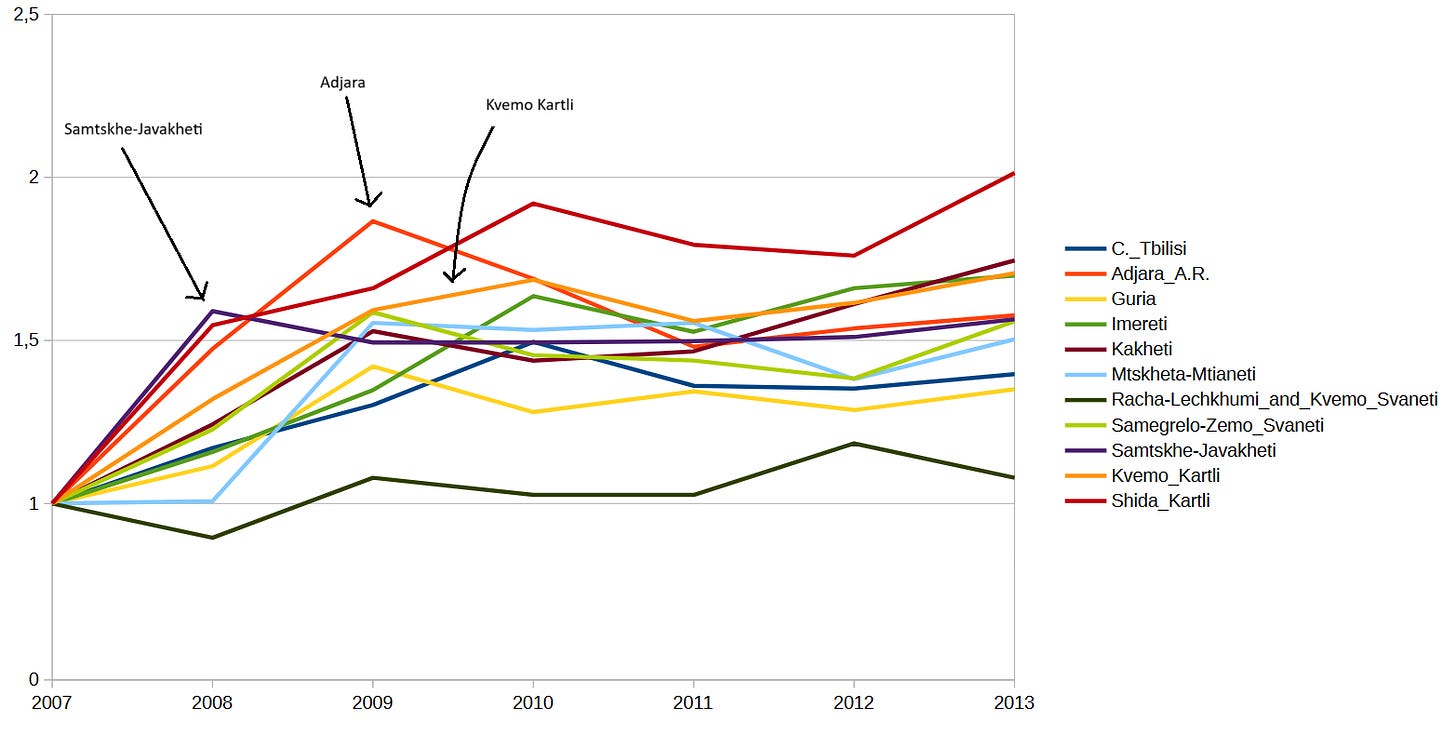

As I mentioned earlier, Georgian births data is not only segmented by year but also by region (mkhare). This allows us to examine trends in third-order births in the three Georgian regions which have a substantial non-Georgian Orthodox population - Adjara, Kvemo Kartli and Samtskhe-Javakheti - and compare these regions with the other, overwhelmingly Georgian Orthodox regions of the country10.

Kvemo Kartli region is 43% Muslim; the autonomous Republic of Adjara is 40% Muslim; and Samtskhe-Javakheti region, while Christian, has a subtantial (40%) Armenian population who follows the Armenian Apostolic Church, which is led by its own (not birth promoting) Patriarch11.

If the increase in third-order and higher births in Georgia was due to Patriarch Ilia’s baptism campaign, Muslim Georgians, who don’t baptize their children, and Armenian Georgians, who may wish for their children to be baptized, yet by their own Patriarch, should not be affected in their birth decisions by Ilia’s efforts.

And considering that these religious minorities constitute a significant portion of the population in these regions, the religious effect - or lack of effect more accurately - should be evident in a chart of 3+ births by region:

As you can see in the chart, the three regions with proportionally fewer Georgian Orthodox residents are among those that experienced the most significant increase in 3+ births in the years following Patriarch Ilia’s announcement12.

This is exactly the opposite of what one might expect if the raise in 3+ births was driven by Georgian religiosity and sparked by Ilia’s campaign.

Unlocking prosperity

If Ilia’s campaign was not the cause of the Georgian increase in childbirths during the late 2000s, then what caused it?

One possible explanation is hinted at in Stone’s report:

the entire observed fertility increase occurred in married fertility, while unmarried childbirth actually fell. Now, married childbirth was rising slightly even before 2008, the first year when Ilia’s policy can really be expected to have had a significant effect, which suggests there may have been an underlying trend upwards.

This is illustrated in the next chart:

Births within wedlock decreased dramatically during the 1990s and early 2000s while births within wedlock increased substantially, remarkably during a period of religious revival following decades of Soviet rule.

Since you cannot have births within wedlock unless people marry, let’s now look at the trend for marriages in Georgia.

I also plotted the yearly Total Fertility Rate (TFR) for the same period from 1994 to 2023. You’ll notice that the number of marriages started increasing a few years before fertility rates began to rise. Georgian births, particularly those within wedlock, follow the increase in marriages13 with a delay of around 3-4 years. And this also aligns with a small increase from 1.62 to 1.69 children per woman between 2006 and 2007, prior to Ilia’s announcement.

It seems Georgians are inclined to marry before having children, and they suddenly began marrying in greater numbers around 2003-2004, years before Patriarch Ilia came up with his mass baptism campaign14.

Now that we have a likely proximate cause for the increase in births, there’s still the question of why did the number of marriages start to rise in 2003-2004.

Assuming Georgian soon-to-be-married couples, like most couples in culturally Christian countries, aspire to have stable, well-paying jobs and a home of their own, marriage would have been a challenging prospect in the late 1990s. At the time, Georgia was still grappling with its post-Soviet economic downturn and the tragedy of Soviet architecture1516.

Then, in early 2003, construction began on the Baku–Tbilisi–Ceyhan (BTC) oil pipeline, which traverses Georgia, bringing with it the promise of an economic transformation through transit fee revenues and access to cheap gas17. In November 2003 the Rose Revolution toppled Georgian President Eduard Shevardnadze, setting the stage for the election of reformist President Mikheil Saakashvili in January 2004:

Saakashvili reformed the economy by cutting red tape which had made business difficult, courting foreign investment, simplifying the tax code, launching a privatization campaign, and tackling widespread tax evasion. Due to the establishment of a functioning taxation and customs infrastructure, the state budget increased by 300% within three years.

More and more foreign investment flowed into Georgia, wages rose, and the economy continued to expand.

And construction companies started building homes, enabling young couples to become married couples with a home:

And, eventually, have (more) children.

The Georgian Orthodox Church’s campaign to incentivize births simply “got lucky”. It happened to coincide with a period when birth rates were going to rise regardless.

Tbilisi, the fertile

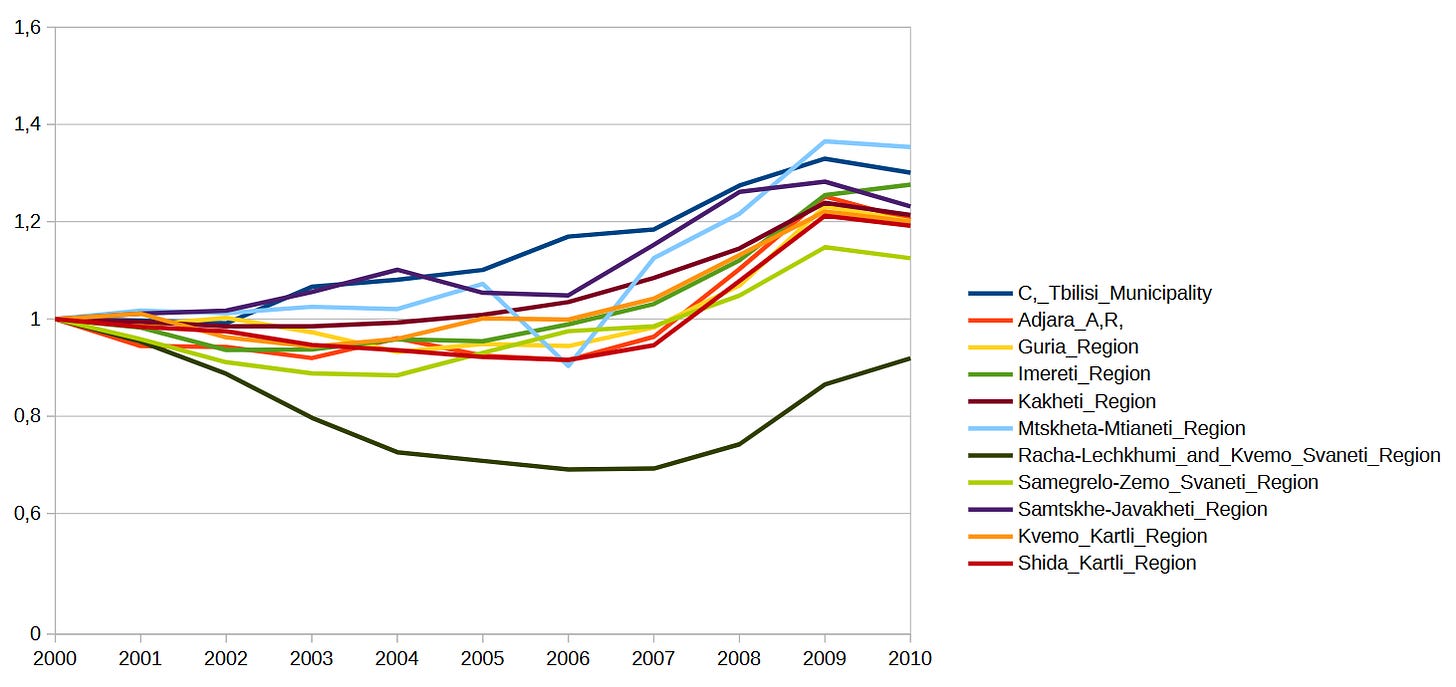

I did check whether this economic hypothesis18 holds true at the regional level, and apparently it does. The following chart shows the average monthly remuneration of employed persons for each Georgian region:

Tbilisi, the capital, unsurprisingly19 shows the steepest salary increase across the entire country, surpassing all other regions by 2005-2006.

How does that compare to the increase (or decrease) in births across each Georgian region during the same period?

This chart shows the change in all births, not just 3+ births. Economic factors should influence all births, not just those of three or more children.

Note that Tbilisi consistently ranks first or second in the increase in birth numbers from 2003 to 2008. And Mtskheta-Mtianeti (in light blue on the charts), another region experiencing a significant increase in average salary, ranks third or higher in number of births throughout most of the same period.

Also, Samtskhe-Javakheti region (in purple on the charts), which saw the most substantial increase in industrial production - and presumably industrial jobs - of all regions from 2002 to 2008, clearly belongs in the same births increase category as Tbilisi and Mtskheta-Mtianeti.

Follow the money

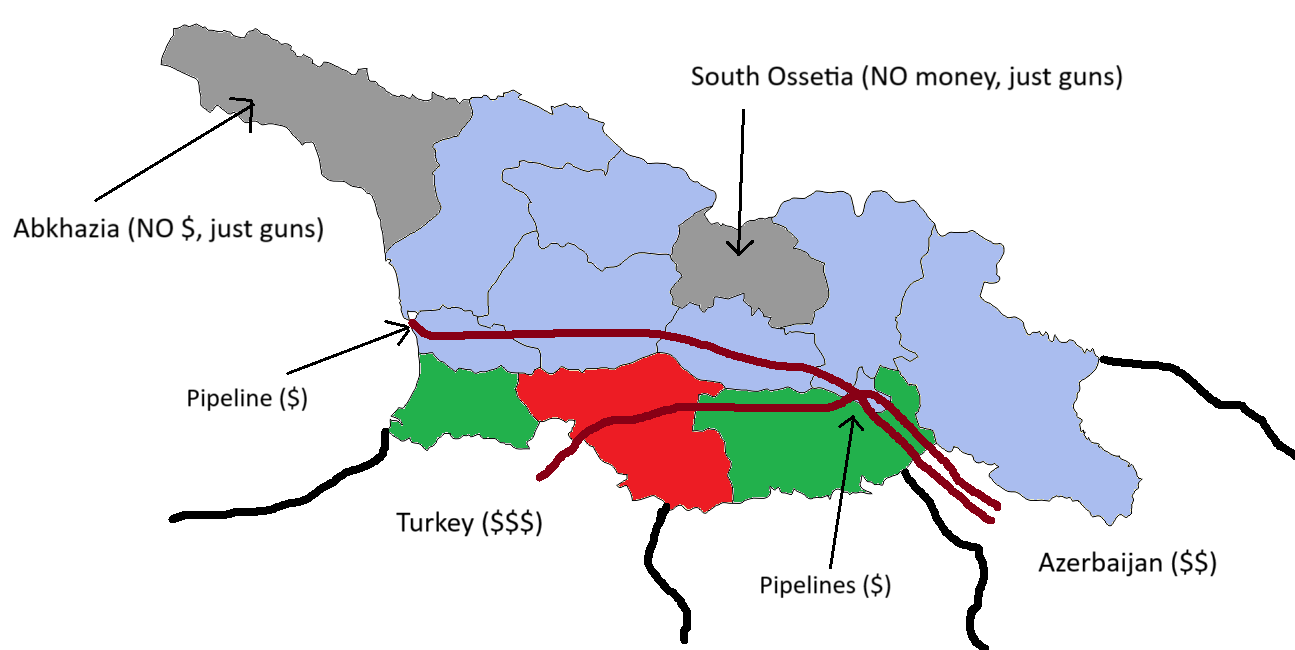

By the way, the most likely reason why Georgian regions with large non-Georgian Orthodox populations had that 3+ births spike is also economic in nature. Those regions are, non coincidentally, located right next to Georgia’s more prosperous neighbors, Turkey and Azerbaijan20, and are further away from the conflict-ridden (and poor) separatist regions of Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

They are also located along the path of Georgia’s oil and gas pipelines:

As Bulgaria, another Orthodox Christian country, also demonstrated in the late 2010s, campaigning with mass baptisms as a strategy to raise birth rates simply does not work.

TFR for a certain year is the expected average number of children that are born to a woman over her lifetime, based on the births in that specific year.

Replacement level fertility is the average number of children per woman needed to maintain a population’s size, generally considered to be around 2.1 children per woman.

Can you make out the “I”s?

Caveat: In 2023, the most recent year with reliable data, Georgia’s TFR was 1.7, the lowest in 16 years. This might indicate the end of Georgia’s relatively high fertility period, or it could be a temporary dip.

Stone, the author of the report I previously quoted, references a paper by Giorgi Tsuladze et al. which makes the case for the relative unreliability of Georgian demographic data. However, I found no mention in the paper of factors that could distort the reporting of birth order for Georgian births or cause any discontinuity in general birth reporting post-2007 (in fact, the paper was published in 2002).

From 2007 to 2008, the figures are 26% vs 21%, so more or less the same scenario.

Geostat.ge does not provide data broken down by birth order prior to 2005.

I used media reports that cite the total number of baptized children in specific years, coupled with the data on the number of 3+ births from Geostat.ge.

Even Tbilisi, Georgia’s capital and largest urban center, which might be expected to attract numerous immigrants from other (Muslim) regions of the country, only has a small minority (1.5%) of practicing Muslims. Kakheti and Guria regions are only 12% and 11% Muslim.

His correct title is not Patriarch, but Catholicos.

The only other region that experienced an increase in 3+ births comparable to the three aforementioned regions was Shida Kartli.

Divorces trail marriages also. A spike in divorces began in 2007, only leveling off around 2014.

Dear Ilia: I know you have the best of intentions, but there’s no reason to hurry people into doing what they’ll end up doing anyway.

For a vivid yet hilarious depiction of 1990s Georgia, you might want to consider reading Waiting for the Electricity, by Christina Nichol: “In the republic of Georgia, the Communists are long gone, replaced by . . . well, by what? Something much more confusing, that’s for sure. There are no jobs in the cities. And when there are jobs, employees aren’t compensated.”

I should really explain here why other former Soviet countries didn’t experience the same sudden increase in births that Georgia experienced. My intuition is that it has to do with the issue of marriage (“religiosity“ after all?).

A parallel gas pipeline apparently began construction in 2004.

It’s not just its privileged position as the country’s capital, but also both gas and oil pipelines pass through Tbilisi.

At the time, more prosperous.

Fascinating stuff, as a non-Georgian who has lived in Georgia continuously for 8 years, it makes a lot of sense to me. I am somewhat religious, and most people I know are moderate to very religious, but being able to afford diapers and doctors visits and a good maternity hospital seems to have a big impact on having kids. Also important, it seems, is having an optimistic view of the future. Whether someone here loves or hates Saakashvili, everyone knows implicitly that 2003 was really the major turning point for the country. It tracks with the prosperity argument for sure.

It was a great read and offered another interesting hypothesis for Georgia's birth boom. Lyman Stone recently posted a new paper on the religious nature of the birth boom. Which may interest you or your readers. Cheers.