The Spanish-American War, the 98 Disaster and the ensuing Spanish "crisis"

Regarding the (almost) final chapter of Spain’s colonial history and the bad bad consequences of losing its colonies.

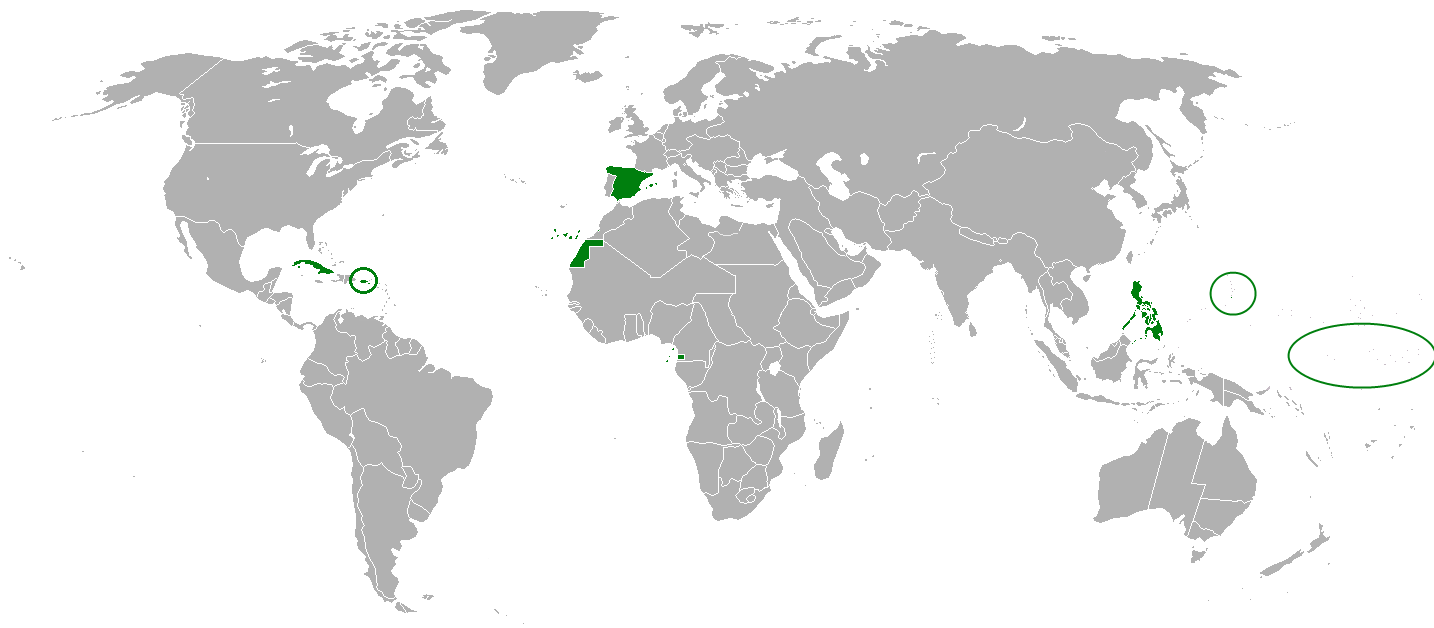

Having once held sway over one of the largest colonial empires in the world, Spain’s defeat in the Spanish American wars of independence during the early 19th century left the European nation as the master of a much reduced overseas domain, consisting mainly of the islands of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippine archipelago.

Even in its diminished state, this colonial empire continued to yield undeniable benefits to Spain:

It offered Spain a captive market for its manufactured goods - mostly Catalan textiles. Even though Spanish industry remained very limited.

Migration to the colonies, specially Cuba, acted as a safety valve for Spanish society, allowing poor peasants to try their luck across the ocean. Urbanization and industrialization progressed slowly in 19th century Spain compared to most Western European countries, yet Cuba still had plenty of land and opportunities.

That warm fuzzy feeling of being part of an empire.

Yet all of this would come to an end in 1898 with the outbreak of the Spanish–American War.

By the time the United States declared war on Spain, following the mysterious and as of yet unexplained sinking of the USS Maine, the declining Iberian empire had been battling a Cuban insurrection for 3 years and a rebellion in the Philippines for almost two years. A final Spanish defeat in Cuba was probably just a matter of time.

January was customarily the month in which the Spanish army command launched vigorous field operations… But nothing happened. In January 1898, Máximo Gómez wrote of a “dead war.” The collapse was all but complete. “The enemy… is in complete retreat from here, and the time which favored their operations passes without their doing anything.” Spain’s failure to mount a new winter offensive confirmed the Cuban belief that the enemy was exhausted and lacked the resources and resolve to continue the war1.

Once the United States got involved, the superiority of the U.S. navy over the Spanish fleet drove the conflict to a swift end with the almost complete destruction of Spanish naval forces2.

After signing a peace protocol in August 12, 1898, the Spanish government braced for the imminent loss of much of its overseas empire3, while trying to avoid the outcome they dreaded the most:

When it becomes clear that [Spanish Marshal Ramón Blanco] cannot succeed or that the United States must intervene, the Queen will have to choose between losing her throne or losing Cuba at the risk of a war with [the United States]. [Ministers] Sagasta and Moret are patriotic Spaniards. They wish peace. I believe that they have done and are doing all they can. If they fail and have to choose between war with [the U.S.] or the overthrow of the dynasty, they will try to save the dynasty4.

The question was not if the Spanish Empire would lose territory, but how much of it. And as long as the monarchy and the Spanish constitutional system, based on the 1876 constitution, could withstand the blow of the Spanish defeat without collapsing, most Spanish politicians were content with a diminished empire.

In fact, on September 13, 76% of Spanish deputies approved a law authorizing the Spanish government to renounce its right of sovereignty and cede overseas territories5. Perhaps the painful legacy of a 19th century marked by frequent, often violent regime changes had instilled in Spanish deputies a desire for stability over other considerations.

This seems to have been the sentiment expressed by Spanish Prime Minister Práxedes Mateo-Sagasta during his intervention in the law’s discussion:

Thirty-six years on international wars, civil wars, and colonial insurrections has Spain wasted so far this century, which is soon to end. That is to say, gentlemen, that we have consumed more than a third of our life in wars with foreign countries and in fratricidal struggles, devouring one another, with enormous colonial insurrections in which we have exhausted all our resources and shed the blood of the nation’s children6.

The war resulted in the Spanish loss of Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Guam as formalized in the Treaty of Paris, signed on December 10, 1898. This agreement between Spain and the United States was eased not only by the aforementioned law, but also by the suspension of the Spanish parliament (Cortes) the day after the law’s approval7.

The Spanish parliament would not be reconvened until February 20, 1899, only to be suspended again due to the resignation of the Sagasta government on March 1, 18998. This followed days of acrimonious parliamentary debates focused on the recent war, including a proposal for a new constitution that would supposedly help to regenerate the nation.

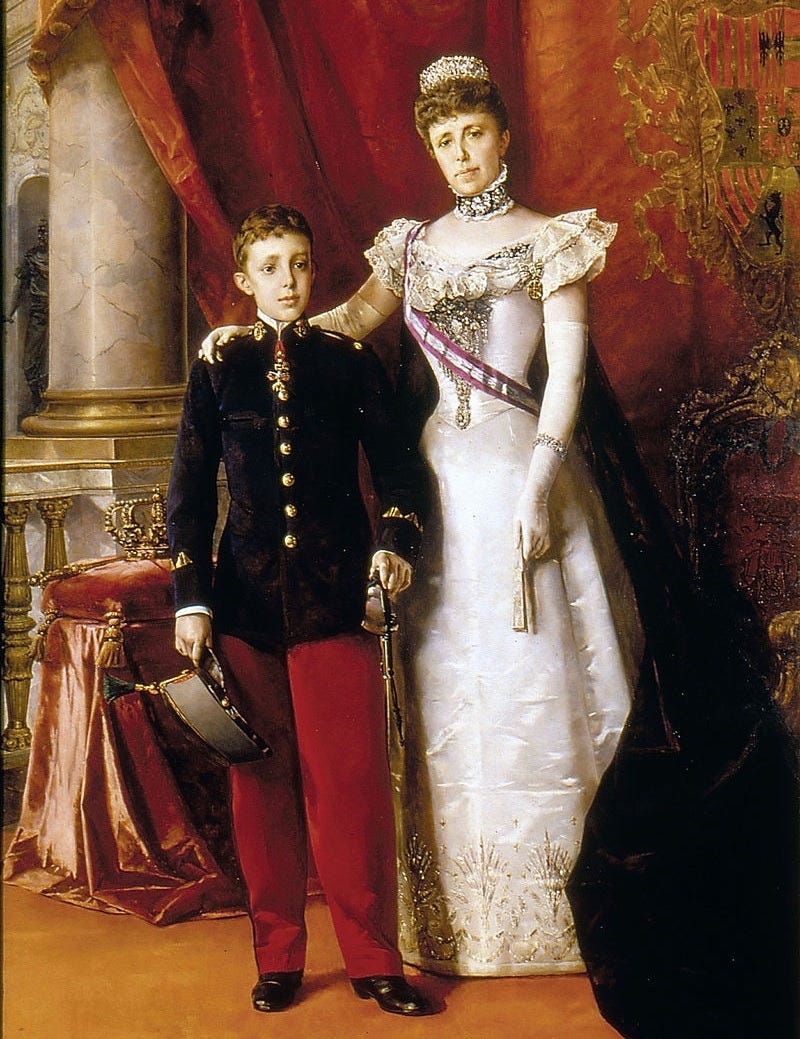

Under these circumstances, it’s not surprising that the ruler of Spain at the time, Queen Regent Maria Christina, opted for a government change to avoid another - perhaps violent - regime change, specially one that could end her rule and jeopardize the future reign of her teenage son9.

A new beginning or a new crisis?

Despite the military debacle, the Queen Regent remained optimistic while inaugurating the new Cortes in June 1899:

The most pressing and difficult of the tasks your mandate imposes upon you is to put the public treasury in order, liquidating the financial burdens of wars and disasters, and addressing them with ordinary and permanent resources... a persistent and judicious effort, restoring credit and making capital cheaper, will provide [the people] with the conditions of modern economic life and will allow [the people] to recover in a few years the ground lost in more than a century10.

Her hopeful message seemed to be: as long as we manage to pay off the war debt, everything will be okey dokey.

Was the Queen Regent right?

According to Spanish historian Francisco Romero Salvadó, the answer is no.

The… starting point is the deep and abiding trauma of 1898, of military defeat by the United States and the consequent loss of the remnants of Spain’s colonial empire. In an age when international status was measured by colonial possessions this was, as Romero makes plain, a mutilating blow, made worse by America’s parvenu status. Immediately, the weaknesses inherent in the system under which Spain had been governed since the restoration of the monarchy in 1875 were made plain11.

Trauma and mutilation are not ok, and they suggest the defeat had devastating consequences. But maybe that’s just Romero’s opinion, and we should look at other historians’ views on the impact of the 1898 war on Spain.

Like that of reputed historian Manuel Tuñón de Lara:

From [1898], as we have seen, the standard of living among the people deteriorated rapidly. How long did it take for awareness of this situation to develop, or more precisely, for awareness of the need to react? Although our data are very incomplete, it seems that the unrest began in 189912.

That also sounds bad. But maybe that’s just the opinion of a couple of well-known historians, not a consensus opinion?

Let’s look at what a random history website, which may reflect the consensus view better, has to say:

The empire’s disintegration led to a profound socio-economic upheaval… The socio-economic ramifications of the 1898 Crisis were severe and multifaceted. Economically, the loss of colonies deprived Spain of critical markets and resources, leading to increased unemployment and poverty levels… The immediate aftermath saw a decline in agricultural production and an increase in food prices, further straining the populace.

Or maybe what this other site says:13

The loss of the last Spanish overseas colonies due to the war with the United States in 1898 represented a major crisis at all levels in Spain, to the point of mortally wounding the Restoration regime.

The 1898 crisis had significant economic and cultural consequences for Spain. Economically, the loss of the colonies represented a significant blow, as important markets and resources were lost. Furthermore, the country experienced a deep recession and a decline in foreign investment.

Or, lastly, this guy’s tweet on X, which incidentally persuaded me that the notion of an economic crisis due to the loss of the colonies was common:

After presenting such a needlessly long list of sources to support my argument, I have to admit that this is not necessarily the consensus view on the 1898 on the Spanish-American war, but it’s prevalent enough that it it made it into Wikipedia:

the moral, political, and social crisis in Spain produced by the loss of the colonies of Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines, and Guam after defeat in the Spanish–American War

At the beginning of the 20th century, Spain had not recovered from the blow to its influence in international politics, as well as the political and economic crisis that the Spanish-American War of 1898 brought with it, with the loss of Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Philippines and, to a lesser extent, the Mariana Islands and the Caroline Islands.

By now, you probably suspect - if you caught my very subtle ironic tone - that I disagree with this view. I’m now going to elaborate on why I disagree, and to what extent do I reject this view.

You should pay your taxes

Let’s start with the supposed economic crisis.

I’ve already mentioned that the Queen Regent was well aware of the need to “put the public treasury in order, [and liquidate] the financial burdens of wars”, and so it should come as no surprise that the new government she selected - she was the Spanish sovereign after all - vigorously pursued a policy program to address those needs.

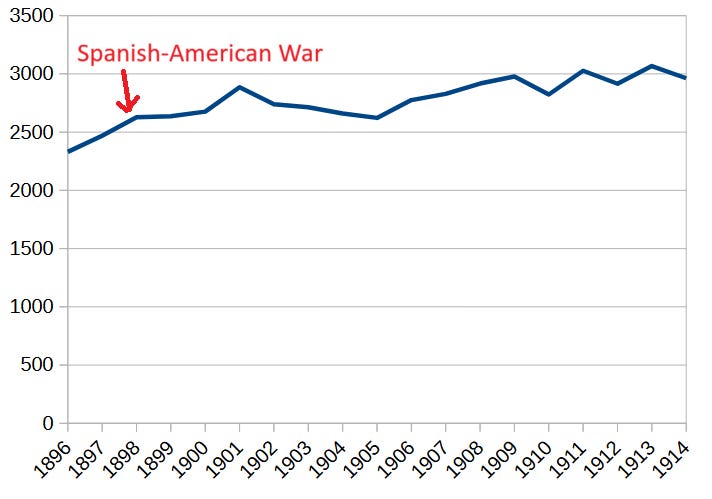

Yet in the years following the Disaster, inflation fell, the overall level of exports rose, and the state budget enjoyed a record surplus. The cost of achieving these economic targets was high. The brief regenerationist Government of Francisco Silvela carried out a severe programme of higher taxation and public expenditure cuts which helped to solve the state deficit but aroused the ire of broad sections of the population15.

And despite the pain caused by economic restructuring, the Spanish economy managed to keep going.

Considerable restructuring took place in those economic activities most dependent on the colonial markets, such as textiles, with the result that many workers lost their jobs and the first mass-strikes broke out in protest. However, the post-war fall in the value of the peseta encouraged exports in other sectors of the economy. Considerable amounts of capital were repatriated as the colonial Spaniards returned and many firms showed unusual agility in seeking out new markets in Latin America, Europe and to a smaller extent in North America. Exports to the ex-colonies did not fall as dramatically as had been expected, because consumer tastes and needs there favoured some Spanish consumer goods over those of their US competitors16.

The Spanish economy adapted to the new conditions imposed by the defeat, while austerity and restructuring produced the desired effects. The fact that these policies worked was not a surprise, specially to those who had long seen the futility of the Cuban War.

the French people had a large financial stake in Spain, holding about $400 million in Spanish bonds and having additional large investments in Spanish railroads… [in 1897] The French realized that Spanish bonds would rise in value if the nation cut its losses in Cuba, stopped its large military expenditures, and developed its resources at home and in North Africa17.

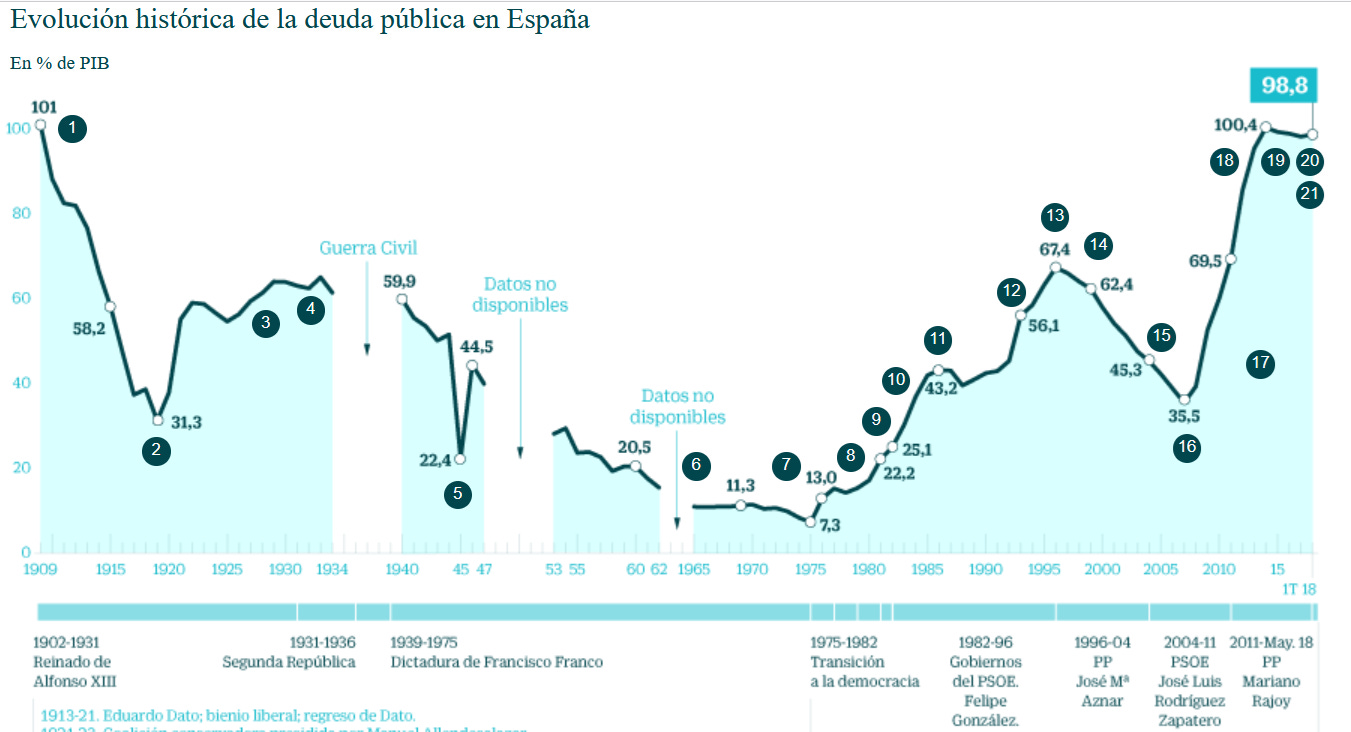

Higher taxation and public spending cuts are not the most popular policies, but they can do wonders for a highly indebted economy, and as you can see in the chart below, showing public debt as a percentage of Spanish GDP, early 20th century Spanish governments took debt reduction seriously.

The above chart only starts in the year 1909, but you can infer the state of public finances in the 1899-1909 period by the fact that public debt servicing ate up 60% of the Spanish budget early in this period18.

Yet, this enormous burden did not hinder the economy from growing at a healthy, though not spectacular, rate in the years following the war, as you can see in the next chart.

If that’s not convincing enough, a paper by Pedro Fraile and Alvaro Escribano further corroborates that the 1898 defeat had almost no negative impact on the Spanish economy and, in fact, had some positive effects on it.

An econometric analysis of Spanish aggregate and sectoral data reveals that the loss of the last colonial possessions in 1898 was not, in fact an economic disaster of the catastrophic proportions some traditional historians had held. Both at the aggregate level and in the sectors most directly involved in the colonial trade, the events of 1898 were not a specially relevant watershed…The third part of the essay analyzes the trends and cycles of the most important series affected by the Disaster… to conclude that far from the disastrous impact usually assigned to the colonial losses of 1898, [the Disaster] had, in fact, beneficial consequences for the Spanish economy, specially through the inflow of capital that the war produced.19.

So, if there is no evidence of an economic crisis, what about a social crisis?

Labor strikes and riots

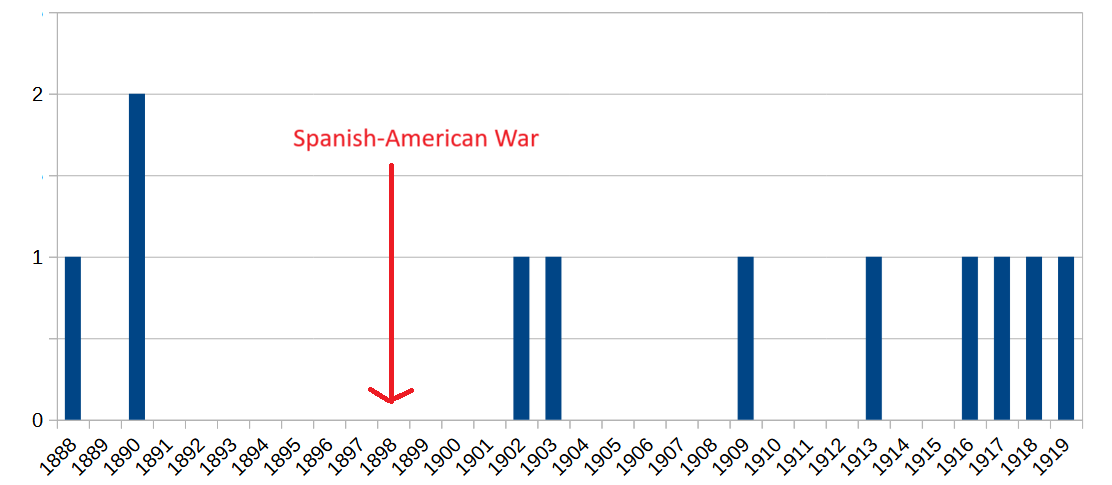

I wanted to know whether the years immediately following the 1898 war show any increase in labor strikes, which could indicate a social crisis, but I couldn’t find any comprehensive list of Spanish labor strikes spanning the last decade of the 19th century and the first decades of the 20th, so I simply compiled a list of strikes based in a very limited Wikipedia article and a few suggestions by Grok20.

Here’s a chart of labor strikes per year based on my compiled list.

That’s not very informative, to be honest. Major labor strikes are only a small subset of all strikes, and it’s unlikely that analyzing trends in these events will confirm or reject the hypothesis that the 1898 war triggered a social crisis.

Luckily, there’s another type of event that was frequent during this time period and which can be interpreted as an indication of social discontent: the tax riot.

In late 19th and early 20th century Spain, tax riots took the form of Motines de consumos, that is to say, riots against the collection of consumos, an indirect sales tax that accounted for a large part of Spanish public revenue.

And we do have more comprehensive sources of information on consumos riots. Specifically, I found detailed lists for three areas of Spain: Aragon, Asturias and the Cuatro Caminos neighborhood in Madrid21.

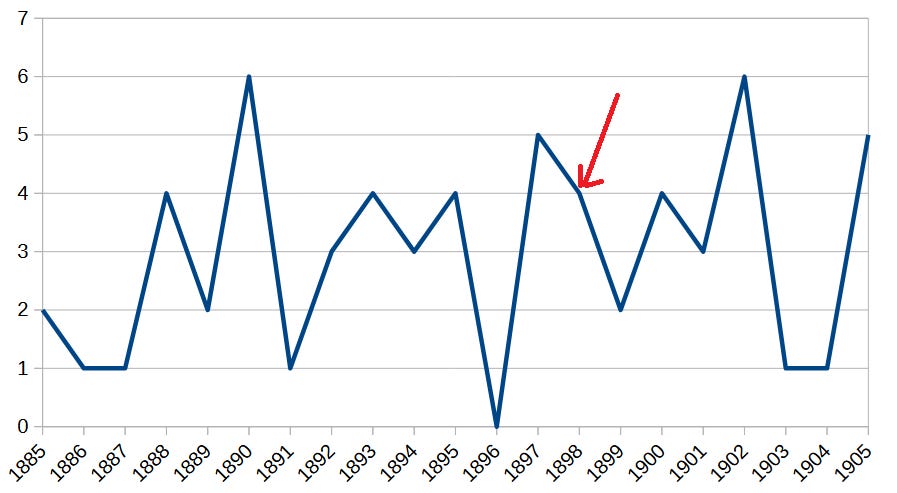

Here’s the chart for consumos riots in the three areas from 1885 to 1905.

I may need more data to see a pattern (adding more areas would be nice), but the chart shows no clear trend.

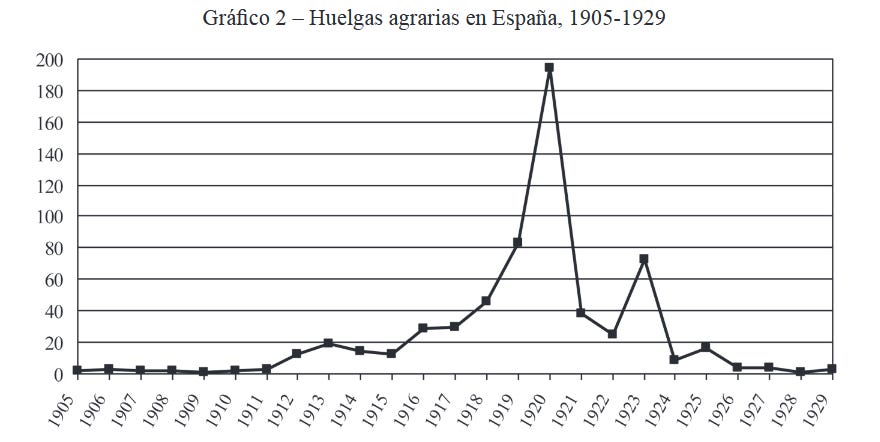

I tried again with agrarian strikes. At the time, Spain remained largely agrarian, with agricultural workers often organizing labor strikes to strive for higher wages and improved working conditions.

So, here’s a chart of yearly agrarian strikes in Spain.

Notice that the chart begins in 1905, not in 1898. Yet, the number of strikes is very low during the first few years and only increases significantly after 1911-1912, more than a decade after the end of the war.

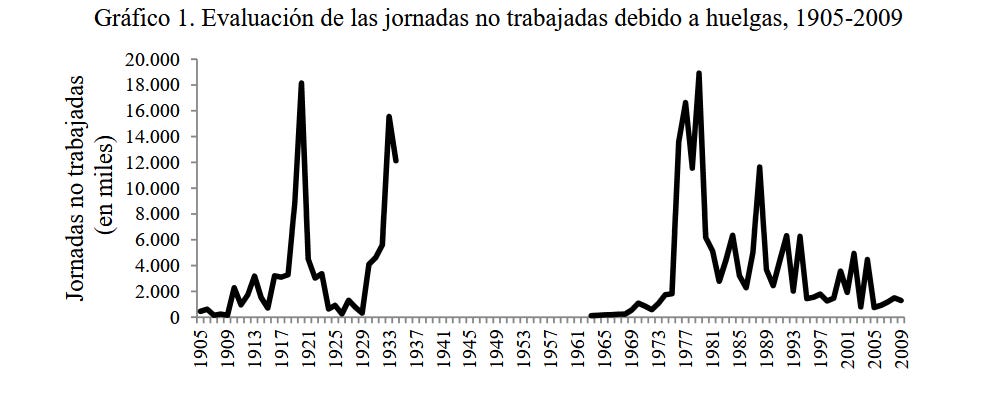

This doesn’t completely rule out the possibility of increased labor actions as a consequence of the defeat, but it does make it unlikely22. Similarly, the next chart shows the number of days not worked due to strikes in Spain from 1905 to 2009, showing a nearly identical trend.

I hope that is enough data to convince you that a social crisis likely did not occur in Spain in the years following the 1898 defeat.

If no economic or social crisis occurred, that only leaves us with the possibility of a political crisis23.

Taking turns

Before diving into the subject of the alleged political crisis, it might be a good idea to take a look at how the Spanish political system worked during the Bourbon Restoration period (1876-1923).

The 1876 constitution granted limited powers to the Spanish parliament, composed of a congress of deputies and a senate, while the King (or Queen) retained the authority to dissolve or suspend it at any time.

Governments, headed by a President of the Council of Ministers, were appointed and dismissed by the monarch at will, though usually after consulting the main political leaders. This meant that, despite deputies being elected for five-year terms, only once during the half-century Restoration regime did a government serve a full five years, while the typical Restoration government lasted just over a year on average24.

The two main parties, both characterized by weak party discipline, were the Liberals and Conservatives. Beyond these two dominant parties, Republicans - opposed to the monarchy in principle - and regionalist/separatist parties managed to secure a few parliamentary seats, yet without challenging the hegemony of the two major parties.

With no alternatives outside this duopoly, the King alternated between appointing Liberal or Conservative governments based on the priorities of the moment, giving rise to the contemporary perception that the two parties colluded to take turns leading the country. The so called turnismo.

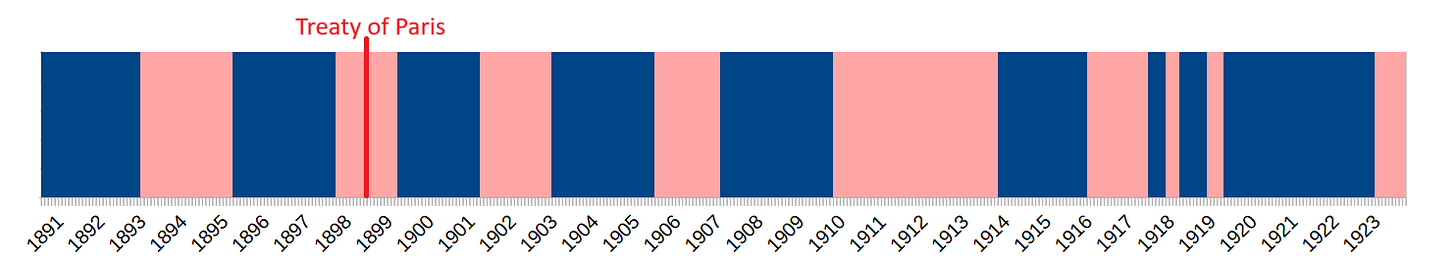

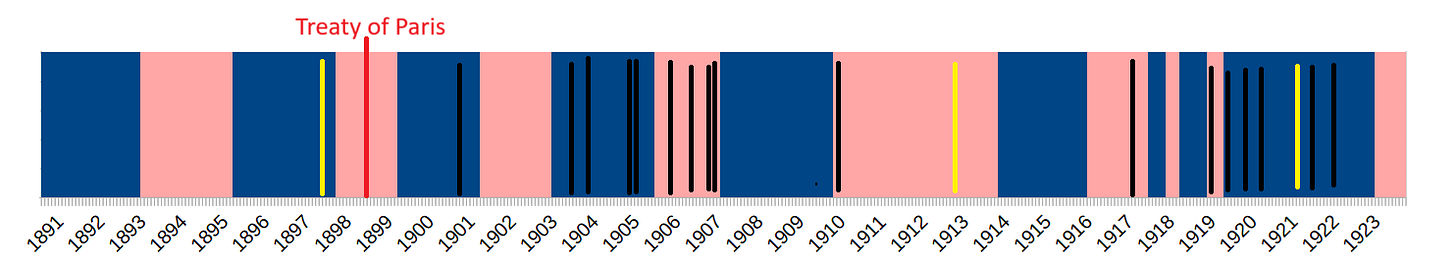

Given this regular alternation of power, the first question we may ask is: did the 1898 defeat disrupt the alternation between Liberal and Conservative governments?

Apparently, it didn’t. As you can see in the previous timeline chart, there is no break in the regular alternation between Liberal (pink) and Conservative (blue) governments after 1898.

Nevertheless, what this timeline doesn’t show are the many changes of ministry that occurred without a change in the ruling party. For instance, between December 1902 and June 1905, five different Conservative Presidents of the Council of Ministers ruled Spain.

I’ve now added to the preceding timeline all the changes of government (black lines) so we can see if there’s any deviation from the pre-1898 trend, and maybe discern the supposed political crisis reflected in the instability of post-1898 governments.

At first glance, the updated timeline seems to suggest an increase in instability after 1898, with black (and yellow) lines appearing frequently in the post-1898 period. But is this really a sign of a political crisis?

It took more than four years from the signing of the Treaty of Paris to the beginning of the first unstable period seen in the timeline (1903-1906), which coincidentally lasted around four years.

That first seemingly unstable period began when the second Francisco Silvela (Conservative) government was replaced by the first Raimundo Fernández Villaverde (Conservative) government. The main reason for the substitution was the inability of the Silvela ministry to agree on a fiscal policy, particularly on the issue of whether to allocate a considerable sum to rebuild the Spanish Navy following its destruction in the war.

Fernández Villaverde, as minister of Finance in the Silvela government, strongly opposed the rebuilding of the Navy due to its excessive cost and budgetary impact, ultimately resigning in March after his stance had been rejected by the other ministers.

He had his revenge in May, when Congress - dominated by his fellow Conservatives - elected him President, signaling widespread political support for his views on the Navy and budget. His election was followed by a long series of heated parliamentary debates centering on the budget and whether it made any sense for Spain to have a modern and powerful Navy at the time.

By the time Congress adjourned for the summer recess, on July 18, the Silvela government had made little progress in persuading a majority of Congress to fund a new naval fleet25, and two days later the King forced the issue by appointing Fernández Villaverde as the new head of government in place of Silvela, ensuring a balanced 1904 budget and no new naval fleet.

That first black vertical line is not a sign of a post-war crisis but of a functioning political system that reacted to the military defeat in the most sensible way: not building a new fleet. The second one, in December 1903, marks the transition from Férnandez Villaverde, having already secured Congress’ approval for his 1904 budget, to the more popular Conservative leader Antonio Maura. This was not a crisis but a predictable outcome of the initial government change.

The third black line, in December 1904, brings up an important factor in Spanish Restoration politics. The military was a major actor in Spanish politics from the Napoleonic Wars to the end of the Francoist dictatorship, and military men were not happy with the defeat and especially resented the lack of a powerful Navy.

In December 1904, Maura found himself in the middle of a confrontation with the King for the appointment of the new position of chief of the Spanish Army Central Staff. Maura’s candidate for the post was General Loño, while the King’s candidate was General Camilo García de Polavieja who, in very Spanish fashion, had entered politics after a long and distinguished military career.

García de Polavieja was a “Regenerationist”, a crisis man:

The sudden popular vogue of General Polavieja, successful in the Philippines and known to have been an opponent of the government’s Cuban policy, shows the persistence of the old belief in salvation from the army… Popular at court, the Christian General was the ideal regenerationist candidate for the conservative bourgeoisie. His attack on civilian politicians who substituted ‘the politics of abstraction for practical reform’ and thus alienated the ‘neutral masses’ represented one of the commonplaces of regenerationism as well as a desire to shift responsibility for disaster from the army on to civilians. His promise of ample decentralization was a bid for support from Catalonia, where the demand for Home Rule was gaining strength26.

Broadly speaking, Regenerationism implied diagnosing a crisis in Spain and proposing solutions to resolve it. That seems too vague - and very appealing to anyone trying to enter Spanish politics, so let’s examine García de Polavieja’s specific proposals as published in his September 1898 manifesto.

In his manifesto, the general advocated army reform and compulsory military service, proposed broad administrative decentralization and the promotion of wealth, and rejected the caciquismo and scandalous political actions of the Restoration parties... his insistence on quickly rebuilding the Navy, as stated in his manifesto27.

In a country recovering from decades of militarism, having wasted many years and countless lives on international wars, civil wars, and colonial insurrections, the King’s candidate proposed solving the “crisis” through further militarism.

Maura, faced with the King’s imposition of a militaristic - and potential strongman - candidate as head of the Spanish Army showed his displeasure with the royal decision by resigning, along with his entire cabinet. That’s the third black line in the timeline.

The young and foolish monarch had imposed his decision28, but the Restoration regime, through its political leaders, managed to keep the country going despite the small setback. García de Polavieja would never take part in any future government29.

A primary goal of the Restoration regime was to get the Spanish military out of politics - of the 27 heads of government that ruled Spain in the quarter-century preceding it (1851 to 1876), 12 had been military men30. And although the Spanish-American War did not create a political crisis, it did create an opening for military meddling.

The series of government changes from 1903 to 1905 does not signal a political crisis of the Restoration regime. Instead, it reveals a remarkably robust political system that effectively dealt with the difficult financial situation derived from Spain’s defeat and resisted attacks on its sensible policies.

You might contend that the timeline shows even more black lines after June 1905, which is true. However, the next black line (December 1905) was, once again, caused by the unwillingness of many Spanish military officers to accept the new situation and adapt to a substantially reduced armed force, together with the young King’s insistence on supporting the men in uniform.

(In fact, this persistent behavior by the King and the Spanish military would be a major factor in the fall of the Restoration regime 25 years after the war.)

There was no post-1898 political crisis.

It was all in your head(line)

If there was no crisis, where did the (not universal but common) perception of one come from?

We know that this notion was already common in the years following the war, at least in the pages of the Spanish press:

The generalized sense of national prostration that followed disaster was summed up by the words of an editorial in the Madrid daily El Correo over two years after the event: ‘Everything is broken in this unhappy country; there is no government, no electorate, no political parties; no army, no navy; all is fiction, all decadence, all ruins...31

And also became common in the works of writers and intellectuals associated with what came to be known as the Generation of 98.

by the end of the nineteenth century, in response to the national identity crisis provoked by the 1898 Disaster… caciquismo ceased to be just one of the many problems troubling the Spanish political system. It became the fundamental problem, the key to explaining the backwardness of Spain and the overriding obstacle to the urgent modernization of the country. This attitude is found in the works of the so-called regenerationists, a fertile intellectual group who, while they did not begin writing until after 1898, made a significant impact on the thought of that time.…Oligarchies and caciques, brought together by the provincial governors, prevented progress in Spain and led to ‘backwardness, misery, ignorance, slavery’32.

Even though the Generation of 98 began discussing Regenerationism in their writings after 1898, their ideological stance drew heavily from the ideas of previous thinkers, particularly Joaquín Costa, arguably the most renowned Spanish Regenerationist.

And what were some of the ideas put forth by Joaquín Costa?

1.- A radical change in the use and direction of national resources and energies... “in short, the de-Africanization and Europeanization of Spain.”

2.- Reform of education at all levels, “remaking and recasting the Spaniard in the European mold.”

7.- “To clean up and Europeanize our currency, through the Europeanization of agriculture, mining, and trade, national education, public administration, and politics, both general and financial, which will restore Europe’s confidence in us.”

Europe good, Spain bad.

Spanish intellectuals, predictably, wrote about the perceived shortcomings of their society - especially when compared to the societies of their European peers -constantly, generation after generation, from the late 19th century until the fall of the monarchy.

All these generations of ‘98, ‘14 and ‘27, those that make up the so-called Silver Age of Spanish literature, were reacting fundamentally against a single one: the nineteenth century, identified with the falseness of party rotation and the monarchical Restoration, against which Krausism, the Free Institution of Education and regenerationism also rose up, all intellectual currents they consider themselves successors to.

In the eyes of the Regenerationists, as long as Spain lagged behind the rest of Europe, there was a crisis and there should be a culprit.

They say that history is written by the victors, yet the market for literature from bygone eras - however imperfect - is dominated by the most expressive, entertaining and prolific writers of those eras, regardless of their status as victors or losers or their historical objectivity.

Cuba: Between reform and revolution, Louis A. Pérez, Oxford University Press, 2015. I do not recommend this book at all.

For context, the United States had roughly 4x Spain’s population at the time, with a per capita income nearly three times higher.

It appears that the Spanish optimistically believed they might be able to keep Puerto Rico and delusionally thought they might hold onto the Philippines as well. See An Unwanted War by John L. Offner and Little Brown Brother by Leon Wolff.

An Unwanted War, John L. Offner, page 91. Quoting American ambassador Stewart L. Woodford. Spanish ambassador Dupuy concurred with Woodford: “The ministers ‘want[ed] peace, if they [could] keep peace and save the Dynasty. They preferr[ed] the chances of war, with the certain loss of Cuba, to the overthrow of the Dynasty.’

Though only 199 deputies voted. See the transcript of the Spanish Congress session from September 13, 1898. Pages 1810-1811.

Spanish Senate session from September 12, 1898. Page 842. In this session, Spanish senators approved the same law that would be ratified the following day by the Spanish Congress of Deputies.

The Wikipedia article on the treaty states that the Spanish parliament rejected the treaty, based on Leon Wolff’s book Little Brown Brother (page 173). This is wrong. The Spanish parliament (Cortes) did not resume its sessions until February 20, 1899.

Throughout this period, the Spanish press avoided openly criticizing the administration’s handling of the military defeat, since the government had suspended constitutional guarantees and instituted press censorship on July 15.

Ironically, the reign of her son, Alfonso XIII, was cut short mainly due to the 1923 coup that ended the 1876 constitutional system. The coup, endorsed by the King, led into the Primo de Rivera dictatorship (1923-1930), whose unpopularity would eventually lead to the fall of the monarchy.

Spanish Congress session from June 2, 1899.

El movimiento obrero en la historia de España, Manuel Tuñón de Lara, 1972, page 357.

This site was the fourth result of a search for “crisis 1898 españa“.

This site was the 16st result of a search for “crisis 1898 españa“.

The Crisis of 1898: Colonial Redistribution and Nationalist Mobilization, Sebastian Balfour, 1999, pages 181-182.

The Crisis of 1898: Colonial Redistribution and Nationalist Mobilization, Sebastian Balfour, 1999, page 181.

An Unwanted War, John L. Offner, page 60.

“Spain, 1808-1975”, Raymond Carr, page 479.

The Spanish 1898 disaster: the drift towards national-protectionism, by Pedro Fraile and Alvaro Escribano, 1997.

X’s AI chatbot. The question I asked was: can you list the 10 most important labor strikes that took place from 1888 to 1920 in Spain? Grok also included an 1892 riot in its answer.

Rioting was more common in large cities.

Manuel Morales Muñoz in La voz de la tierra. Los movimientos campesinos en Andalucía (1868-1931) (2015) notes a small increase in labor actions during 1902-1903.

I’m not going to spend any time arguing against a moral crisis.

It didn’t help that three Presidents of the Council of Ministers (Prime Ministers) were assassinated while in office.

Several potential compromises were proposed by the government: limiting spending to Spain’s three main naval bases (no new ships) or delaying expenditures from 1904 to 1905. None of them seemed to persuade most deputies.

“Spain, 1808-1975”, Raymond Carr, page 478.

El General Polavieja y su manifiesto regeneracionista en la crisis de valores de 1898, Alfredo López Serrano, 1996.

Article 53 of the constitution gave him that prerogative.

In Politics and the Military in Modern Spain, Stanley Payne erroneously claims that “Immediately after the closing of the Cortes, the young king made Polavieja Minister of War“ (page 93), which is false. García de Polavieja was not a minister of the transitional Azcárraga government (Dec 1904 - Jan 1905; that’s the fourth black line) or the subsequent second Fernández Villaverde government.

It’s worth noting that 5 of the remaining 15 were journalists.

Riot, regeneration and reaction: Spain in the aftermath of the 1898 disaster, Sebastian Balfour, 1995.

Political Clientelism, Elites, and Caciquismo in Restoration Spain (1875—1923), Javier Moreno-Luzón, 2007.