The declining appeal of Hollywood: another piece of the puzzle.

More on the decreasing international appeal of Hollywood.

In my last post on the subject of Hollywood’s declining appeal to international audiences, as measured by the share of its revenue that comes from international markets, I speculated that the cause of this trend might be cultural.

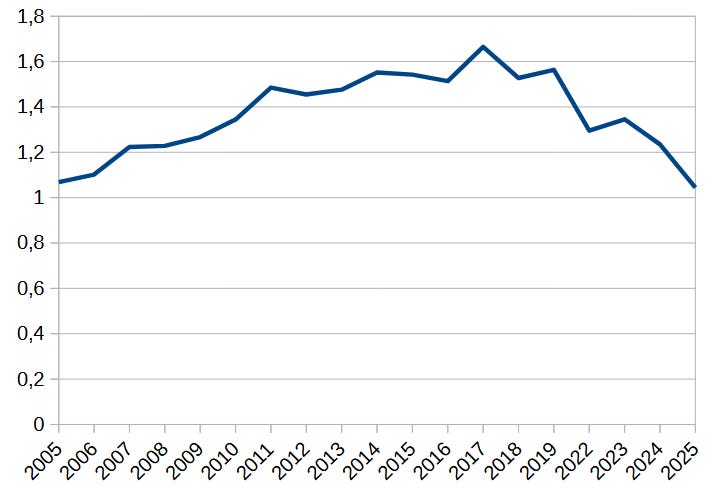

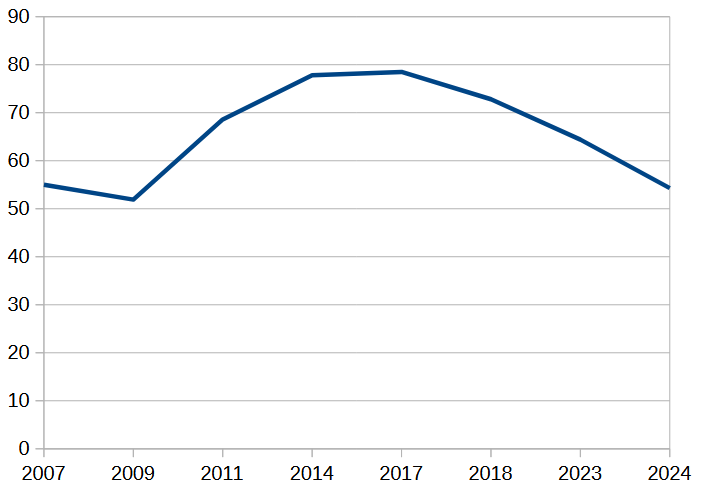

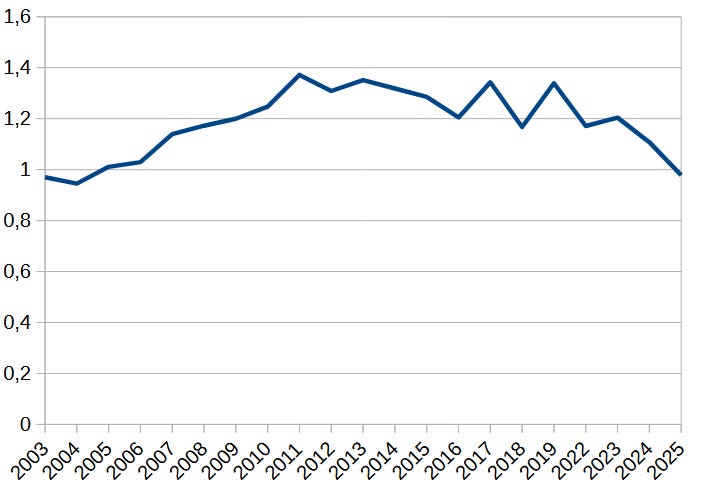

For each year, from 2007 to 2024, I calculated the ratio of international box office revenues - excluding Canada and the United States - for the top 200 highest grossing films of that year (numerator) divided by the domestic box office revenues for the same films (denominator).

I observed that the trend of a decreasing international box office share, beginning around 2019, also holds for franchises like the Spider-Man and Transformers series of movies. Since franchises, characterized by their common subjects and shared cast of characters, form a series of closely related entertainment offerings, the declining demand for them in international markets suggests a change in the tastes of international movie audiences.

Hollywood keeps offering a similar product, yet over time, non-American moviegoers become less and less interested, likely reflecting cultural changes in international markets.

I also noted that movies directed by American directors are less appealing to non-American audiences, implying some kind of (higher?) cultural mismatch between American directors and foreign audiences.

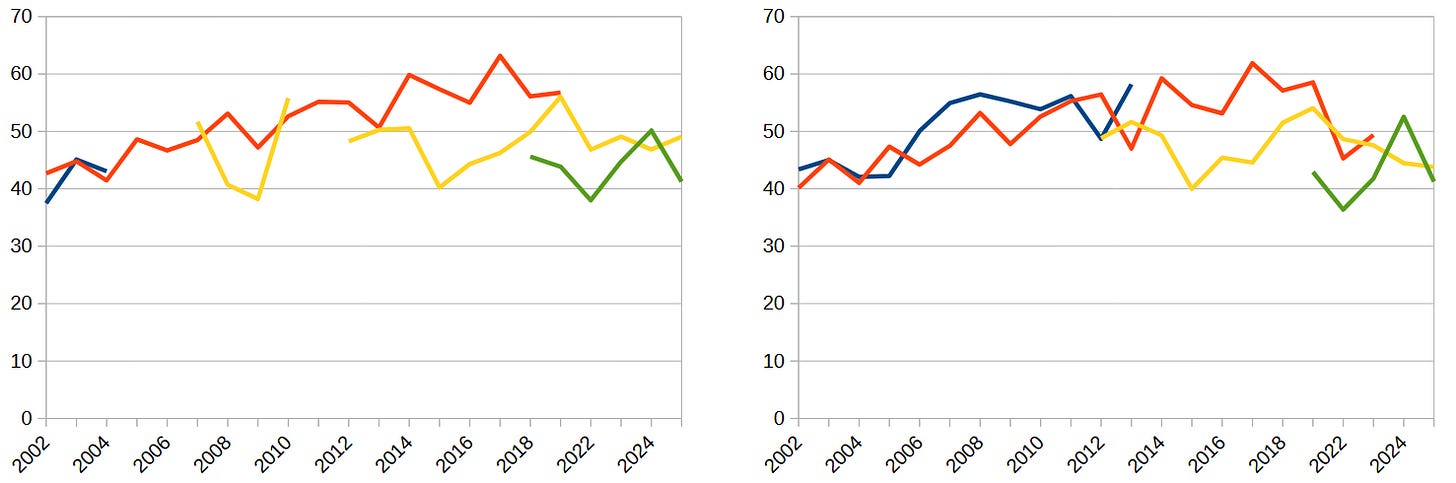

You can see in the chart that the average international revenue share of non-American directors is consistently higher than the international share of American directors (aside from 2007).

I now want to add another important piece to the puzzle of the disappearing international movigoer1. But first I need to address a small issue with the general trend of rising international share before 2014 and declining share post-2019.

Hollywood goes to China… and then leaves

In response to my previous post, several people pointed out the effect of the Chinese market on Hollywood’s box office performance. Perhaps the rising trend in international revenue share before 2014 was caused by China’s rapid transition from poverty to middle-income status and its consequent exploding demand for Hollywood’s films?

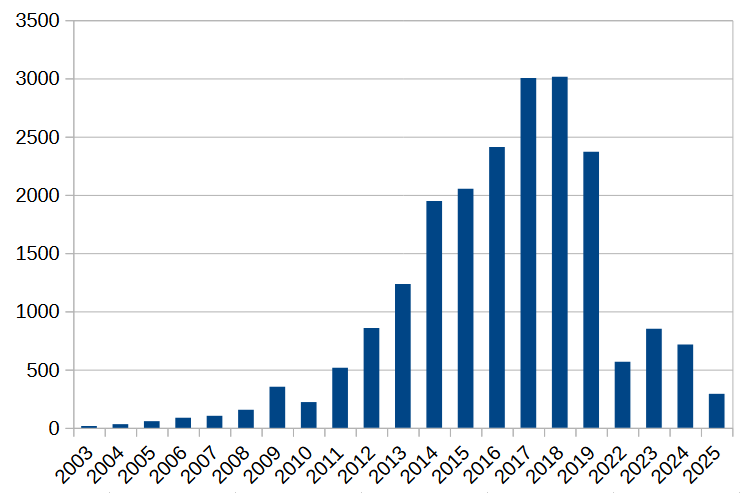

China’s box office did explode, going from $16 million in 2003 to $1.9 billion in 2014, so the pre-2014 rising trend can be attributed, at least in part, to the huge expansion of the Chinese market. At its peak, China represented nearly 10% of Hollywood’s total box office.

And then, following a deterioration of relations between the United States and China in 2018-2019, China’s appetite for Hollywood movies collapsed.

The pre-2014 rise and post-2018 collapse align with the trend I described in my previous posts2, making it reasonable to assume that the Chinese film market might fully explain the observed trend.

Yet it doesn’t. The trend is still there after excluding China from the total international box office and the shape of the curve is roughly the same:

The updated curve now shows two peaks, in 2011 and 2017, rather than just in 2017 when including China, suggesting that my previous assumption of a 2014 start date for the inflection period - when the curve transitioned from a rising trend to a declining trend - may be wrong. The inflection period could have begun earlier than 2014.

China’s case is particularly interesting because it offers a clear candidate for the cause of the declining box office and it suggests where to look for potential causes of other box office declines. It would be interesting to see if any other country shows a revenue drop that coincides in time with a deterioration in its relations with the United States.

Could I do a similar (admittedly superficial) analysis for other major international markets, such as Europe, Latin America or Asia? Well, not for the time being, but I hope to do that analysis in the future3.

Let’s now move on to the actual subject of this post: what else can I say about Hollywood’s decline in international markets besides the fact that American directors are less appealing to international audiences than non-American ones.

Categorizing directors as American or foreign is just one of many ways in which we can partition the set of all Hollywood filmmakers. Because the data I’ve used spans from 2003 to 2025, directors from the early years of this time period comprise a distinct subset from the directors of the 2020s. Some are too young to have been active in 2003, while others, born in the 1940s or before, are too old to remain active in the later years.

This generational churn creates an opportunity to examine the international box office data in a new way. Old Hollywood directors may not have been active during the same period as those from the younger Hollywood age cohort, but I can define an additional middle-aged cohort consisting of directors who worked alongside the older generation. And maybe some of these middle-aged ones were still active when the younger generation became dominant in Hollywood.

In fact, I can define four or five different age cohorts and, for each, compare various characteristics of the films they made against those of other cohorts - and yes, the one characteristic I have in mind is the international share of revenue.

I can’t define too many age cohorts because then each one would have so few directors as to make any comparison meaningless. Therefore, I made sure each cohort directed at least 10 movies each year so as to make comparison with another cohort meaningful. This approach allowed me to calculate a yearly average international share of revenue for at least two cohorts (almost) every year.

I also excluded non-American directors from this analysis to isolate the effect they have on international revenue, and tried to have at least three distinct American cohorts to work with.

But ended up defining four.

(I did not use the conventional American generational labels of Boomers, Millennials, Generation Ç, or whatever Americans call them. They are arbitrary and they mostly exist so that lazy journalists and editors can save some time when writing catchy - usually inaccurate - titles for their next piece. Believe me. I can be a lazy writer. I know what I’m talking about)

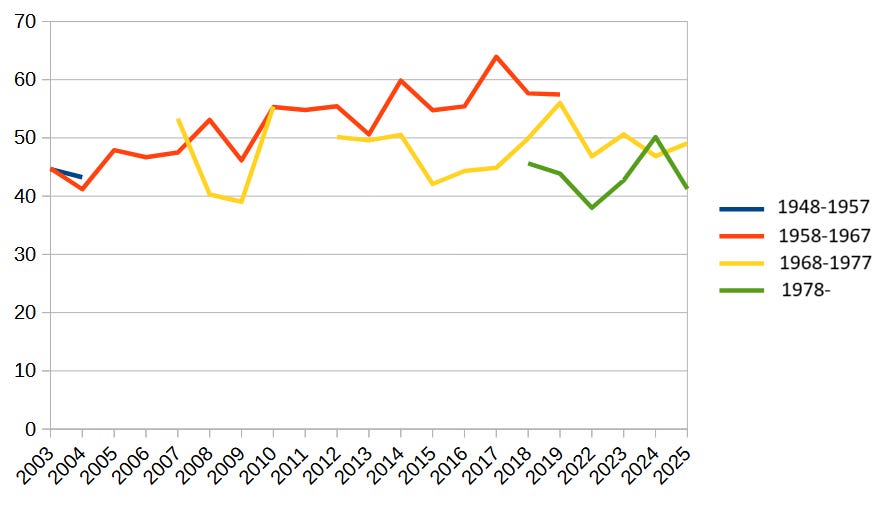

The four cohorts are:

Directors born between 1948 and 1957. The oldest cohort.

Directors born between 1958 and 1967.

Directors born between 1968 and 1977.

Directors born after 1977. You could call them the youngest cohort.

(I first tried to use 1980 - a nice round year - as a boundary year, but there are too few directors born after 1980)

What does the average international share of Hollywood revenue for each of these four age cohorts look like?

You’ve certainly seen prettier charts.

Except for the years 2018 and 2019, there are enough movies (10 or more) to calculate the average for only one or two cohorts each year. We can compare the oldest cohort against the 1958-1967 cohort, 1958-1967 vs 1968-1977, or 1968-1977 vs the youngest.

I’d rather not comment on the first of those three comparisons for now, given that the oldest cohort has only two data points, but I will comment briefly on it in the conclusions.

The 1958-1967 (red) age cohort is largely characterized by a higher international box office share than the younger 1968-1977 (yellow) cohort. Only in two years (out of twelve) did films made by the 1968-1977 cohort achieve a higher international share. Thus, although the limited available data (movies per year, directors) is not enough to assert with certainty that the pattern is real, it does suggest American directors from the 1968-1977 cohort, currently aged between 47 and 57, are less appealing to non-American audiences than their older counterparts.

Finally, the comparison between the 1968-1977 (yellow) age cohort and the youngest cohort shows a similar pattern. Movies directed by the older cohort (1968-1977) show a higher international box office share than those by directors from the youngest cohort. From 2018 to 2025 (six years), only the year 2024 deviates from this pattern.

Being shifty

Before drawing any conclusions from the preceding observations, I wish to underscore the limitations or weaknesses that these comparisons between cohorts suffer from.

Even though Box Office Mojo, my source for movie box office figures, provides data for 200 films each year, the usable subset of Hollywood movies is much smaller than 200. And only some of those movies are directed by Americans or Canadians4.

Also, some directors’ Wikipedia pages do not record a year of birth or birthplace, or they list this information in a non-standard way that makes parsing difficult (and I’m too lazy to put in the effort to deal with those cases).

In brief, the dataset I’m using is smaller than ideal.

Another possible weakness I should discuss is, I think, pretty obvious: did I cherry pick the four age cohorts defined above to fit my narrative?

The short answer is: no, trust me.

The long answer is that I made sure the results are not sensitive to the boundary years I chose for the age cohorts I defined.

I carried out two additional calculations of the international share of revenue, spanning the same time period, using two alternative definitions for the four age cohorts. The first shifts all the cohorts to the left, starting or ending one year earlier; for example, the 1968-1977 cohort becomes the cohort 1967-1976. The second shifts all the cohorts to the right, beginning or ending one year later; in the case of the youngest cohort, this means it now starts in the year 1979.

Here are the charts for the two sets of shifted cohorts (same colors as before).

The left shifted chart looks almost exactly as the original chart. The right shifted one shows some differences but not significant enough to invalidate the observations I made based on the original chart. In particular, the right shifted chart seems to suggest that there is little difference in international appeal between directors from the oldest cohort and those from the 1969-1978 cohort.

Given these results, I don’t think the differences between cohorts are just an artifact of the boundary years I chose.

Conclusions

Looking at the trends I presented in my last post alongside the new insights derived from comparing the 1958-1967 cohort to the 1968-1977 cohort, and the 1968-1977 one to the youngest cohort, I have to conclude that American Hollywood directors are less appealing to non-American moviegoers than foreign directors, and the younger the American director the lower the international appeal.

I don’t believe this is a demand-side phenomenon. I can’t think of any good reason why international audiences would consciously prefer movies by older directors over movies by younger directors. Which leads me to think this is not a deliberate choice, but a preference driven by what (American) directors put into their films. It’s a supply-side phenomenon.

To quote myself:

The most likely reason for the higher international share of non-American directors is that they contribute something personal (their culture?) to their work and that something makes their films more appealing to non-American audiences.

You could also argue that American directors contribute something (American culture??) that makes their films less appealing to international audiences.

I’m not yet certain whether the demand-side factor - international audiences changing tastes - or the supply-side factor plays a heavier role in decreasing Hollywood’s international box office share, but I’m now pretty convinced that both factors drive this trend.

There’s another issue I have to mention, and it relates to the diminished appeal of younger directors.

The right shifted chart I presented above, to test the sensitivity of these results to changes in the boundary years, has a much longer oldest cohort curve spanning 12 years. This longer curve clearly shows the close similarity between the international box office share of the oldest cohort from 2002 to 2013 and that of the 1959–1968 cohort during the same period. The oldest cohort has a higher share, though the difference is small enough that I doubt whether it’s real or not.

It looks like the international share goes down with each new generation of American directors, starting with the 1969-1978 age cohort, or maybe even with the 1959–1968 if you think there’s a real difference between the oldest and 1959–1968 cohorts.

In either case, this appears to be a medium-term phenomenon, not a long-term phenomenon. Something changed. And it’s driving non-Americans away from Hollywood.

Fine. Maybe not disappearing, but increasingly uninterested.

Part of the problem is that the list of countries with available box office data is not consistent across movies.

The share of American directors roughly varies from 60% to 75%.