No, this is not a metaphor for a proposed rapprochement between the US and the Maduro regime. This was an actual historical event that took place in 1958 in Venezuela, in which Richard Nixon played a central role, years before his groundbreaking visit to China.

But before discussing the two Dicks1 at the center of this story, let's explore the historical context of Nixon’s 1958 visit to Venezuela.

If you read my earlier post on the life of Teodoro Petkoff you might recall that I mentioned several changes of government during Venezuela's mid-20th century history, many of them mediated by coups, including the fall of dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez in January 1958.

Pérez Jiménez, who hailed from Táchira State like most of the key figures in Venezuelan politics in the first half of the 20th century, participated as a young lieutenant colonel in the 1945 coup that brought Rómulo Betancourt, the leader of the left-wing Democratic Action party, to power as President of a Revolutionary Government Junta. This marked the beginning of a three-year period of Democratic Action (AD) rule in Venezuela known as Trienio Adeco. In 1948, the Trienio Adeco was brought to an end by yet another left-wing coup, barely 9 months after the election of Rómulo Gallegos as president2.

The 1948 coup, led by Colonel Carlos Delgado Chalbaud and Pérez Jiménez, ushered in a new dictatorial era that would last until the 1958 coup. This period can be divided into three distinct phases. The first phase was characterized by the rule of a triumvirate led by Delgado Chalbaud, who was known for his communist sympathies3, until his assassination in November 1950.

During the second phase, the two remaining military leaders appointed a civilian, lawyer Germán Suárez Flamerich, to serve as president. He governed the country until free presidential elections were held in November 1952. However, as the election results were not favorable to Pérez Jiménez's party, he decided to annul the elections and assume power as provisional president, marking the beginning of the third phase of this dictatorial era.

The initial move to overthrow Pérez Jiménez began with a failed coup attempt led by Colonel Hugo Trejo4 on January 1. This was followed by a significant general strike on January 21. The strike seemingly served as a powerful signal to those who had been waiting for the right moment to remove Pérez Jiménez from power:

On the 22nd, senior military leaders meet at the Military Academy to consider the situation. Their deliberations conclude by forming a Military Government Junta that asks Pérez Jiménez to resign. On the night of the 22nd, the Navy and the Caracas Garrison spoke out against the dictatorship; and Pérez Jiménez, deprived of all support in the Armed Forces, fled in the early morning of January 23….At news of the overthrow, the people took to the streets, looting the houses of the regime's supporters, attacking the headquarters of the National Security and lynching officials.

The newly formed Junta was led by Admiral Wolfgang Larrazábal alongside three Colonels and a General5. However, a purge occurred just one day later, resulting in the replacement of two Colonels considered too closely aligned with Pérez Jiménez6 (by whom, it’s not specified) with two civilians, cementing Larrazábal’s leadership position.

This was the government that Nixon would encounter upon his arrival in the Venezuelan capital of Caracas.

Goodwill tour

In the context of the United States' foreign policy during the 1950s, aimed at fostering the economic development of Latin American nations and supporting freedom-loving countries, it is not surprising that the U.S. recognized the newly formed Venezuelan provisional government, which promised to hold free and fair elections as soon as possible.

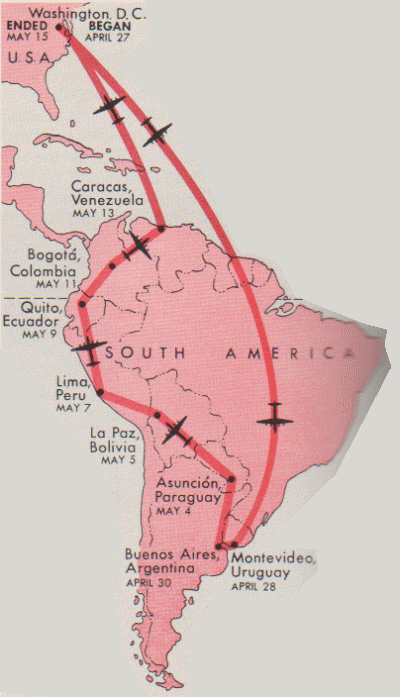

Pursuing this policy, and with the intention of increasing engagement with Latin America, in April 1958 United States President Dwight Eisenhower sent his Vice President Richard Nixon on a goodwill Latin American tour, visiting eight countries: Uruguay, Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, and Venezuela7.

Nixon dutifully arrived at his first stop in Uruguay on April 28, and continued his tour without major issues until his arrival in Lima, Peru, on May 7:

The first serious trouble on the tour materialized in Lima, Peru. Nixon's scheduled appearance at the University of San Marcos saw a large crowd of student demonstrators awaiting his arrival... Over the next few minutes, Nixon spoke with the students. However, a second faction of demonstrators soon began stoning the group, hitting one of Nixon's staff in the mouth and grazing the vice president's neck. The vice-president then withdrew and a later round-table with student leaders was canceled. Returning to his hotel, Nixon and his staff had to push through demonstrators who had encamped outside, during which Nixon was struck in the face.

The Peruvian Government, embarrassed by the violent attacks against Nixon, expressed its regret and condemned the incidents. And despite the gravity of these events, Nixon decided to continue with his South American tour.

But before we proceed any further with Nixon’s tour of South America, it may be worthwhile to take a look at the political and economic climate in Venezuela under Junta rule. This will provide insight into the state of the country that the American Vice President encountered when he arrived in Caracas.

The social truce

In 1957, the Venezuelan Business Federation, which was the main representative of the country's industries and commerce, still supported Pérez Jiménez. However, after his downfall, the Federation conveniently shifted its allegiance to the Junta8:

the President [of the Business Federation] highlighted in an event held at the White Palace in support of the Junta. It was criticized, among other things, specifically that the dictatorial Government had abandoned agriculture

They were not completely wrong about agriculture. Although it was not the Pérez Jiménez government that had abandoned agriculture. Farmers were abandoning agriculture and moving to the cities in droves.

While rapid urbanization was a common trend in most Latin American countries during the 50s, the pace of migration to Venezuelan cities was one of the fastest in the continent9.

Per capita income had surged by 70% from 1947 to 1957, largely due to an oil windfall. With the Venezuelan state receiving 50% of oil profits, the cities, particularly Caracas and Maracaibo, became the focal point for those seeking to benefit from the new oil fueled state largesse.

If you believe the new Larrazábal government must have had it’s hands full trying to avoid a resource curse, managing all that oil wealth in a responsible way that would avoid inflation, and fostering the growth of other economic sectors beyond oil, you might be surprised that this was not their primary focus.

By March the Venezuelan political and economic elites had reached a consensus to establish a social truce, labor peace and national unity10.

This consensus eventually solidified into a political pact signed by the Business Federation and the main Venezuelan trade union, the Unified Labor Union Committee (CSU), which, among other points, established11:

The convenience of celebrating Collective Contracts for each economic branch that tend to standardize working conditions and stabilize worker-employer relations.

This was less than what the trade union had demanded, as their demands included establishing maximum prices for essential goods and lowering housing rents.

The new government was also worried about the very high levels of unemployment12 and decided to solve the problem by implementing an Emergency Plan, which involved recruiting 18,500 workers to undertake minor public works while receiving what was then called an “idleness salary”13.

Maybe these policies of the Venezuelan government were not a sign of a radical leftist ideological inclination. Had that been the case, it would have created an awkward situation during Nixon’s visit, who was an avowed anti-communist.

Need a house?

As a result of the influx of people migrating to Caracas and other cities, informal settlements started to emerge on the outskirts of these urban areas, where newcomers would reside. The Pérez Jiménez government initiated a series of public works projects, financed by oil revenues, including among them14 the building of housing to accommodate these new urban dwellers.

The centerpiece of these housing projects was the new December 2 neighborhood, named in commemoration of the (fraudulent) presidential election that marked the beginning of Pérez Jiménez's rule as de facto president. Following his overthrow, the recently completed housing projects were swiftly renamed January 23 to celebrate his downfall15.

What happened then?

Buildings were invaded and apartments squatted by the slum dwellers from the surrounding hills. The Venezuelan Communist Party did very effective political work among these people, and they were very hostile to the Betancourt regime.16

Larrazábal’s government chose not to evict the squatters.

Then in July 23, the Minister of Defense, General Jesús María Castro León, voiced his opposition to the replacement of two Junta members, the previously mentioned civilians, by two new members. In particular, the appointment of José Antonio Mayobre, a former communist17, as a new member displeased many military officers.

Later that day, the situation escalated as Castro León presented a list of demands to the Junta, including the exclusion of the Communist and AD parties from the Venezuelan government.

Ultimately, Castro León's sabre rattling failed to sway Larrazábal, and the situation was resolved the following day through Castro León's resignation as Minister of Defense18.

Castro León's gamble had a subsequent chapter in September when a group of mid-level officers led a failed uprising in Caracas. Their objective was to express solidarity with Castro León and his supporters, while also voicing their disapproval of Larrazábal's government, which in their words was leading the country to economic disaster and the Armed Forces to division19.

Perhaps these actions by Castro León and others were an overreaction to the economic and social policies implemented by the government, which were being misinterpreted as a reflection of a particular ideological leaning by Larrazábal and his associates. But it would be unwise to blindly trust the judgment of Castro León and his supporters without further evidence.

Granted, the events I just mentioned happened in July and September, after Nixon’s visit in May 13, nevertheless they provide valuable context for understanding Venezuela's political landscape in 1958 and the inclinations of its provisional government, and how those factors might explain the reception Nixon encountered during his visit.

Poor Richard

I’ll quote Wikipedia on Nixon’s arrival in Venezuela20:

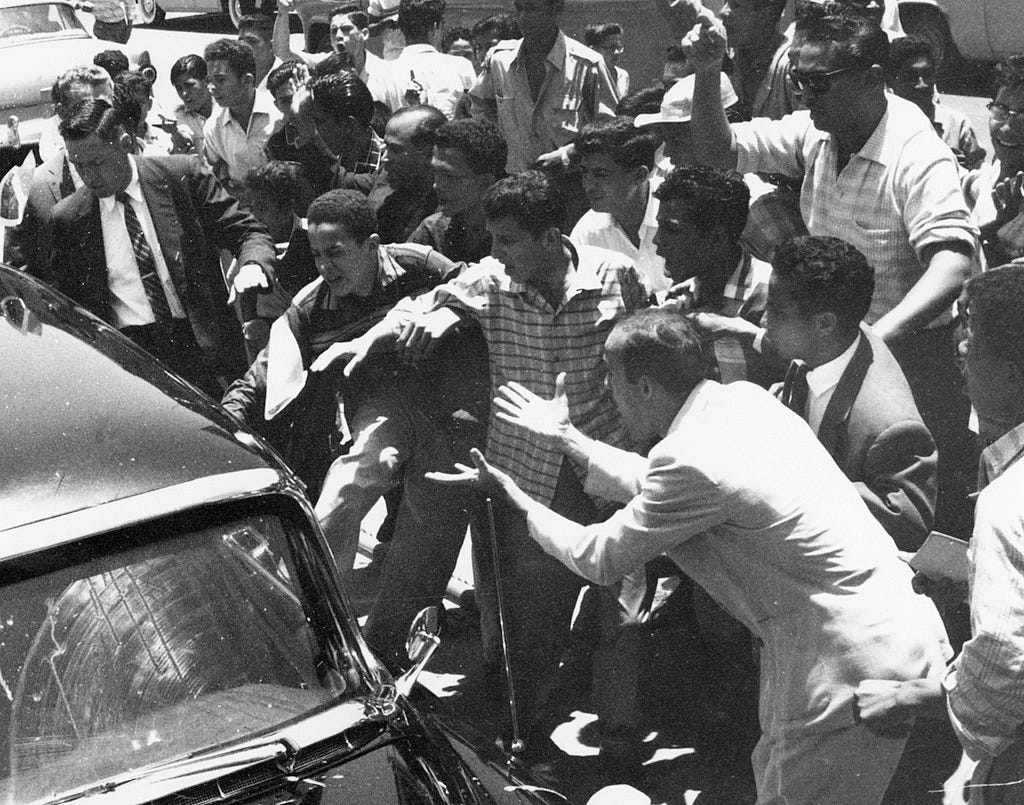

Nixon arrived, via air, in Caracas on May 13, 1958. According to a U.S. Secret Service report of the incident, a crowd of demonstrators at the airport "purposely disrupted ... [the] welcoming ceremony by shouting, blowing whistles, waving derogatory placards, throwing stones, and showering the Nixons with human spittle and chewing tobacco"… The New York Herald Tribune's Earl Mazo wrote that "Venezuelan troops and police seemed to evaporate. The vice-president and the whole official party literally had to fight their way to cars behind a thin but sturdy phalanx of U.S. Secret Service agents". The original itinerary had Nixon moving from the airport to the National Pantheon of Venezuela where he was to lay a wreath at the tomb of Simón Bolívar. However, a United States naval attache sent ahead with the wreath reported a crowd that had assembled at the Pantheon had attacked him and torn up the wreath. At this point it was decided to proceed directly to the U.S. embassy.

Far from a warm welcome. But surely the Venezuelan government would intervene to alleviate the situation.

Life's Wilson wrote that a crowd of several hundred "raced toward their quarry and engulfed Nixon's car", stoning it and banging on the windows with their fists. Nixon was protected by twelve United States Secret Service agents, some of whom were injured in the melee… According to the Secret Service, Venezuelan police declined to intervene to clear the crowd. When the mob began rocking the car back and forth in an attempt to overturn it, U.S. Secret Service agents, believing the vice president's life was in jeopardy, drew their firearms and prepared to begin shooting into the crowd…Nixon ordered Secret Service agent-in-charge Jack Sherwood to hold fire and shoot only on his orders. No shots were ultimately fired

It seems that some Venezuelans thought they knew what was happening.

[Foreign Minister] Velutini explained the police inaction was because the communists "helped us overthrow Pérez Jiménez and we are trying to find a way to work with them". Nixon's longtime secretary, Rose Mary Woods, was injured by flying glass when the windows of the car in which she was riding, following Nixon, were smashed. Vernon Walters, then a mid-ranking U.S. Army officer serving as Nixon's translator, would end up with a "mouthful of glass", and Velutini was also hit by shards…

Maybe Minister Velutini was inadvertently mischaracterizing the situation?

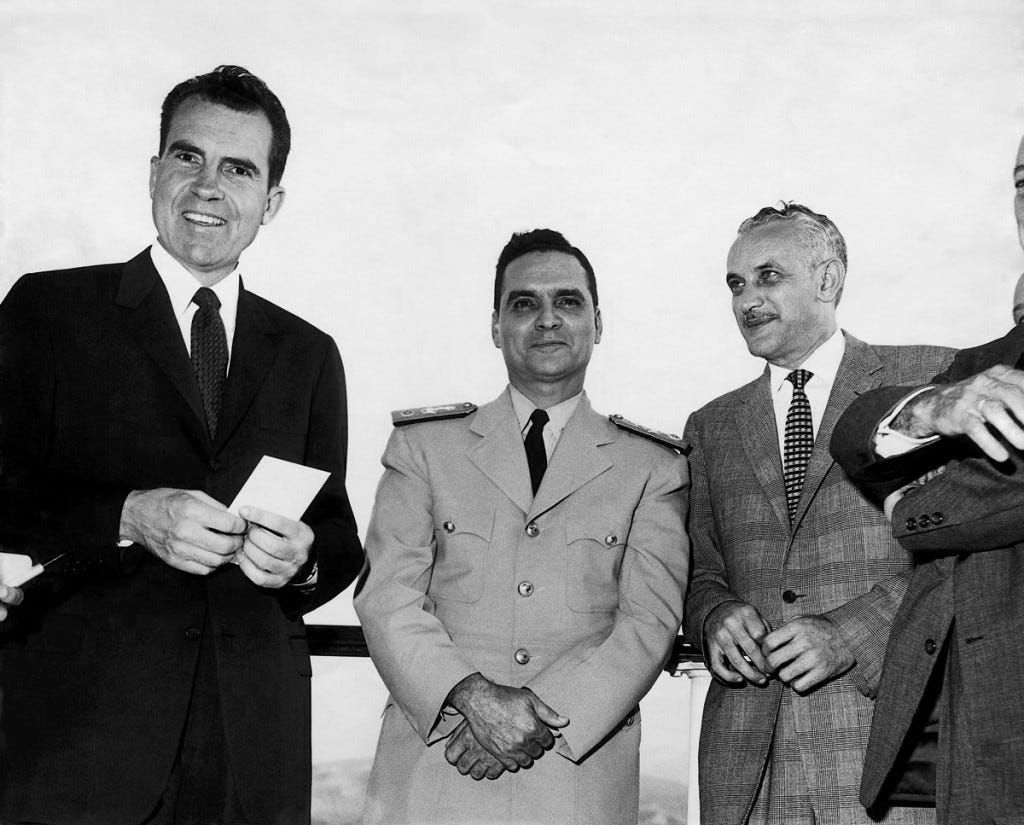

Nixon’s motorcade eventually made it to the embassy, allowing him to proceed with the planned meetings and lunches scheduled for the visit, including lunch with the Junta members.

Concerned about Nixon’s security, President Eisenhower deployed the aircraft carrier USS Tarawa to the Caribbean region to provide potential rescue and support in the event of further threats. The operation, which ultimately was not executed, was named Poor Richard.

I’m not sure whether Richard Nixon learned the right lessons from this event, but he seems to have learned some lessons21:

I believe we support whoever are our friends anyplace in the world. And I believe that in most Latin countries [unclear] not dictators… but, that strong leadership is essential. De Gaulle proved that. I mean, France is a Latin country. It couldn’t—If even France, with all of its sophistication, couldn’t, couldn’t handle a democracy, you can’t... They, they can’t afford the luxury of democracy. Neither can Spain. And no country in Latin America can that I know of. They say, “Well, Colombia.”

Following Nixon's departure, the provisional Venezuelan government persisted in implementing its preferred policies.

Guns and Planning

With the December presidential election still months away, Larrazábal seized the opportunity during his brief tenure to draw on state resources in pursuit of what he believed to be worthy goals.

One of these goals was the success of the Cuban revolution, and recognizing the continuous need for arms of the growing Sierra Maestra insurgency, Larrazábal arranged for a Venezuelan aircraft loaded with weapons to be sent to the Castro-led guerrillas22. That plane not only included those much needed weapons but also carried future Cuban president Manuel Urrutia to the Sierra Maestra23. Urrutia's presidency, however, was short-lived, as he was succeeded by the communist Osvaldo Dorticós just seven and a half months later after acceding to the presidency of Cuba.

Should we conclude Larrazábal was a philo-communist simply because he was arming Fidel Castro’s revolution?

After all, the Venezuelan government Nixon encountered in Caracas was not solely led by Larrazábal. Other Venezuelan leaders were also part of the Junta.

In fact, Larrazábal stepped down from his position as president to run as a candidate for the December election24, which he lost. Edgar Sanabria then assumed the presidency and promptly created a new government office charged with the central planning of Venezuela’s economy.

In that December election, Larrazábal was supported by the Republican Democratic Union Party (URD) and the Venezuelan Communist Party…

Ok, maybe Larrazábal was a commie, and having Nixon travel to Venezuela was a very stupid idea.

Or maybe he wasn’t. While Larrazábal was indeed ideologically left-leaning, he was a quintessential example of Venezuela's political class, particularly among high-ranking military officers who have frequently meddled in the country's political affairs.

These Venezuelan leaders firmly believe in the central role of government in directing and planning the economy, have little regard for political and social stability, particularly when it necessitates setting aside their personal egos, and possess unwavering confidence in the power of leadership. Their leadership of course.

And they have ruled Venezuela not for the last 25 years, but for the greater part of the last century.

I know that Dick is not a nickname for Wolfgang, but Master Mozart would probably not object.

It took more than two years for the revolutionary junta to actually call presidential elections.

Delgado Chalbaud was the scion of a wealthy and well connected Venezuelan family. His father, originally from Mérida State bordering Táchira, was involved in the early 20th-century rebellions that occurred in Venezuela, and after taking the side of dictator Juan Vicente Gómez (1908-1935) established himself as a successful businessman in the naval commerce branch. After siding with dictator Juan Vicente Gómez (1908-1935), Delgado Chalbaud Sr became a successful businessman in the naval commerce sector. However, after falling out with Gómez, he was killed in 1929 while attempting to overthrow the dictator. His son, who also took part in the attempted coup, subsequently fled to Paris and married a Romanian communist student named Lucía Devine. See: Carlos A. Rossi, “The Rise and Fall of the Oil Nation Venezuela“.

Trejo was, yet again, from the Andean region of Venezuela, specifically Mérida State right next to Táchira. And he was, yet again, a left-leaning army officer who would eventually found his own political party, the Integral Venezuelan Nationalist Movement (MNVI). The MNVI backed Hugo Chávez during the 90s, and Chávez - you can’t say he was ungrateful - posthumously promoted Trejo to Army General after his death in 2008.

Colonel Abel Romero Villate served in the Air Force. Colonel Roberto Casanova served in the army. General Carlos Luis Araque, born in Táchira State, was a General in the National Guard. And Colonel Pedro José Quevedo, director of the Military Academy.

It should be noted that Larrazábal had help various positions within the Pérez Jiménez administration, beyond the armed forces hierarchy. These included his appointment as director of the National Sports Institute and director of the Armed Forces (Social) Circle, with the latter one probably contributing to his popularity among other members of the Armed Forces.

I should mention that apart from Argentina, which had banned the Peronist party from politics, and Paraguay, where Stroessner had won a less-than-fair election, all the countries on the tour enjoyed a democratic regime at the time, or were in the process of calling elections. Brazil was not included in the tour because Nixon had already visited that country in 1956.

Luis Lauriño (2015). “Evolución del pacto de avenimiento obrero-patronal, fundamento instrumental del pacto político y del ‘contrato social’ liberal democrático“.

It was certainly the fastest among a group of six major Latin American countries: Argentina, Chile, Colombia, Cuba, Mexico and Venezuela.

Luis Lauriño (2015). “Evolución del pacto de avenimiento obrero-patronal, fundamento instrumental del pacto político y del ‘contrato social’ liberal democrático“.

Luis Lauriño (2015). “Evolución del pacto de avenimiento obrero-patronal, fundamento instrumental del pacto político y del ‘contrato social’ liberal democrático“.

From Elvis Padilla, Jonny Sequera (2005), “Demanda de automóviles nuevos en Venezuela“: “During the period 1958-63, Venezuela suffered a high and growing rate of unemployment, reaching 10.19% in 1958, 12.32% in 1960 and reaching an alarming figure for that time in 1962 of 14.18%. One of the main causes of this fact was the sharp drop that both national and foreign investments suffered, this is evident in the great deterioration that the gross fixed capital formation presented at that time“. In other words, Venezuelans were consuming all those dollars from the production of oil, and moving to the cities where that welath was more easily attainable, but not investing this new found wealth.

Carlos Alfredo Marín (2013). “Dos islas, un abismo. AD-MIR 1948-1960“. In Spanish “salario del ocio“. That was the informal term for the salary given to individuals on the Emergency Plan. Approximately 18,500 workers, representing nearly 2% of the urban male workforce at the time, were “employed” in small-scale public works, such as paving sidewalks, constructing access stairs for hill slums, cleaning sewers and ravines, and other similar tasks.

A very renowned project from the Pérez Jiménez era was the construction of the Caracas-La Guaira highway, a 17 km road connecting the capital city of Caracas with the port of La Guaira. This ambitious project, which cost a staggering 3.5 million dollars per kilometer, was described at the time as the world's most expensive highway.

In 1961, Sucre Parish, the local district encompassing the January 23 neighborhood, had a population of 193,000, a very large increase from its 1950 population of 112,000. This makes sense considering the current population of January 23 Parish, which was split from Sucre Parish in 1966 and now has a population of 84,000.

More on Mayobre: https://venezuelaehistoria.blogspot.com/2018/08/jose-antonio-mayobre-cova.html

Castro León eventually left the country, only to return in April 1960 leading an ill-fated rebellion from his home state of Táchira.

One of the main leaders of the rebellion was Major Luis Alberto Vivas Ramírez, who was born in Táchira. He would go on to lead another rebellion in June 1961.

I was unable to definitively determine whether the airport used by Nixon and his group was La Carlota, located east of Caracas, or Maiquetía, near the port of La Guaira. Former USAF Air Attaché Manny Chavez mentions Maiquetía, but he seems to be a less than reliable witness. Maiquetía underwent significant expansion between 1952 and 1962, coinciding with the infrastructure development boom of the Pérez Jiménez dictatorship.

FOREIGN RELATIONS OF THE UNITED STATES, 1969–1976, VOLUME E–10, DOCUMENTS ON AMERICAN REPUBLICS, 1969–1972. Conversation Among President Nixon, the President’s Assistant for National Security Affairs (Kissinger), the President’s Assistant (Haldeman), the President’s Deputy Assistant for National Security Affairs (Haig), and Director of Central Intelligence Helms.

Previously, in July 1958, Larrazábal had denied sending weapons to Castro. However, in the final months of 1958 he might have felt confident enough to take make the weapons shipment to his favorite guerrilla leader.

Urrutia, like his contemporaries José Miró Cardona (the first Prime Minister) and Roberto Agramonte (Foreign Minister), was a university professor before assuming his political role. Due to his conflicts with other left-leaning members of the revolutionary government, Urrutia was pressured to resign, effectively being mobbed out of his position.

I’m not sure whether Larrazábal was legally bound to resign. He vacated the presidency just 23 days before the election took place.