How bad is skin color discrimination in Latin America?

Analyzing a 2017 paper on the subject of racism in Latin America.

My dear friend A. M. Castellón drew my attention to a 2017 paper by Daniel Zizumbo-Colunga and Iván Flores, titled “Is Mexico a Post-Racial Country? Inequality and Skin Tone across the Americas”, which analyzes the relationship between skin color and educational and economic outcomes in Latin America and the Caribbean.

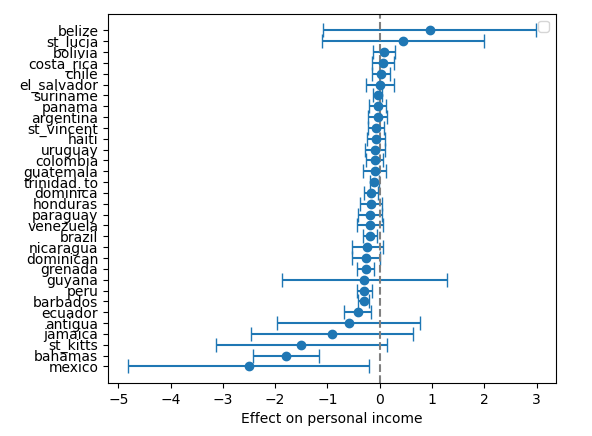

The authors, using data from the AmericasBarometer surveys to do regression analyses, find that the negative economic effect of skin color across the continent is substantial, and particularly severe in Mexico:

Figure 1 shows that the negative toll of skin color on material wealth in Mexico is among the three most extensive in the region, trailing only Trinidad and Tobago and Ecuador1.

As you can see in the previous figure (Figure 1), which presents the regression results from the authors, their findings expose that the scourge of skin color discrimination afflicts not only Mexico but nearly every country in Latin America and the Caribbean. The only exceptions might be Costa Rica and Saint Kitts and Nevis, as their 95% confidence intervals include zero2.

If I understand the chart correctly, the X-axis values in the chart are related to a material wealth scale constructed from the AmericasBarometer survey data3, where each country’s X-axis value represents the change in that scale associated with a maximal change in skin tone (going from the lightest to the darkest skin tone).

To clarify what I, and the authors, mean by changes in skin tone, here’s the color palette interviewers used in the surveys.

In the words of Zizumbo-Colunga and Flores (Z-CF):

Mexicans who were classified by the interviewers as having darker skin tones tend to have lower levels of education and are worse off economically than their lighter skinned counterparts4.

And as Figure 1 shows, the study finds that this holds true not only for Mexicans but for nearly all Latin Americans, even after controlling for variables other than skin tone.

You might think that rural residents have darker skin from sun exposure, and maybe they earn less than urbanites; or perhaps women, who have lighter skin on average, earn less than men. While these are all valid concerns, the study accounts for all these factors.

As I was already familiar with the survey data used in the study, and since I’m very interested in Latin American culture, I decided to take a closer look at this paper and try to replicate its findings.

Income in place of material wealth

The first challenge I encountered when trying to replicate the study’s results was lacking access to the exact material wealth scale defined by Z-CF, despite having all the responses to the survey questions related to material wealth:

Do you have a refrigerator in your household? (question R3)

Do you have a washing machine in your household? (R6)

Do you have a (motor) vehicle? How many? (R5)

Do you have a motorcycle? (R8)

etc…

The good news is, the survey data includes an even better indicator of respondents’ economic standing; one that, in a culture of discrimination, should decrease with increasingly darker skin tones: personal income.

Personal and household wealth are certainly strongly correlated to personal income, yet personal income avoids the effect that personal choices have on some of the material wealth questions5.

So, faced with the apparent impossibility of replicating Z-CF’s material wealth scale, I decided to look at the effect of skin tone on personal income, rather than material wealth.

And at first glance the results hold.

In 19 of the 32 countries studied6, the result is statistically significant (p-value < 0.05). So far, so good.

And just like the authors, I included control variables7 to make sure the effect is not derived from rural-urban differences, etc.

However, just like the authors, I did didn’t control for education.

Controlling for years of education

I’m pretty sure the relationship between education and skin color that the authors found is real, but, after finding that relationship, it makes no sense to then test the effect of skin tone on economic outcomes without controlling for education.

More education increases the chances of finding a better-paying job, earning more income, and acquiring greater material wealth.

Without controlling for education years, you are not really measuring the economic effects of skin tone, but likely measuring the effect on education again.

So, let’s control for years of education, and plot the effects again.

The updated plot shows substantially different results. The effects on personal income are much smaller, and statistically significant in only nine countries.

Nevertheless, the authors’ point still seems to hold: in many LAC countries, darker skinned Latin Americans and Caribbeans experience worse economic outcomes, not due to lower education levels, but seemingly because of the color of their skin.

In fact, both Brazil and Mexico, which together comprise over half the region’s population, show a statistically significant effect, though Brazil’s is far smaller (-0.1888) than Mexico’s (-2.5031).

In the case of Brazil, the -0.1888 value represents the expected decrease in the survey’s personal income scale for an individual with the darkest skin tone compared to the lightest skin tone. In percentage terms, that’s somewhere between 2% and 6%8. In the case of Mexico it’s substantially larger.

Simpson’s paradox

My updated results suggest that Z-CF’s original findings, at least for some countries, represent an instance of Simpson’s Paradox.

In other words, individuals with 10 years of education tend to have darker skin than people who completed 12 years, who in turn are on average darker skinned than those with 15 years, and so on. If those who completed 10 years of education have lower incomes - and less material wealth - than those who completed 12 years, and those with 12 years have lower incomes than those with 15, the overall effect will appear as a correlation between darker skin and lower incomes, even if the effect is entirely due to education.

But this applies only to countries where the effect disappeared after controlling for years of education, right?

Well, seeing as Brazil and Mexico are Latin America’s two most populous countries, and its first and third largest, I decided to check whether the effect might be an artifact of darker skinned people living in poorer regions or lighter skinned people living in richer ones.

For big countries, it seems plausible that some geographical regions might not suffer from skin color discrimination while others do have a culture of discrimination.

Controlling for geographical region

And the results of adding a region control variable are:

The effect is now statistically significant in nine countries, but not the same nine countries as before. Mexico is no longer included, while Saint Kitts and Nevis has joined the group9.

In fact, only three Latin American countries - Brazil, Ecuador and Peru - are now part of the group where skin color discrimination seems to persist after controlling for region, with the remainder being Caribbean countries.

Coming back to Simpson’s paradox, I’ll cite Wikipedia, which quotes mathematician Jordan Ellenberg:

Mathematician Jordan Ellenberg argues that Simpson’s paradox is misnamed as “there’s no contradiction involved, just two different ways to think about the same data” and suggests that its lesson “isn’t really to tell us which viewpoint to take but to insist that we keep both the parts and the whole in mind at once10.”

And in that spirit, we should consider the possibility that there is skin color discrimination in one or more regions of Mexico, even though, when controlling for region, the country as a whole does not show evidence of discrimination.

So here are the results of four regressions I run, each corresponding to one of the four Mexican regions identified in the surveys, to determine whether any of them shows the effects of discrimination.

Notice the (high) p-value and the confidence interval for each region11.

These results indicate that there is no evidence of economic discrimination in any Mexican region once we control for years of education; this is striking given that Mexico, among all Latin American countries, was the central focus of the Z-CF paper.

Brazil, a land of carnival and discrimination?

Having done this regional analysis of Mexico, why not apply it to Brazil? It would be noteworthy if at least one of Brazil’s five regions shows no evidence of discrimination.

Well, applying the same criterion as before (p-value < 0.05), the results indicate that none of Brazil’s five regions shows evidence of discrimination. However, if I relax the threshold to include p-values of less than 0.1, two regions - Center-West and Southern Brazil - show some evidence of possible economic discrimination based on skin color.

While this threshold is not typically used to determine statistical significance, I can’t rule out that discrimination may exist in some Brazilian regions.

Summing up

The 2017 paper by Zizumbo-Colunga and Flores contains a major flaw that invalidates one of its two main conclusions: the claim that economic discrimination based on skin color is widespread in Latin America, which is demonstrably wrong.

The Americas Barometer data does support the conclusion that some Latin American countries - and specific subnational regions - suffer from skin color-based discrimination, with these regions apparently exhibiting some geographic clustering as shown in the map bellow.

You’ll notice I’ve highlighted in pink on the map - indicating likely skin color discrimination - several additional regions in Colombia and Venezuela, based on the regressions I run for each region in those countries.

Even after painting that many regions in pink, these results paint a different, more nuanced picture of discrimination in Latin America (and the Caribbean, if you were paying attention).

Daniel Zizumbo-Colunga, and Iván Flores Martínez. “¿ Es México un país post-racial? La desigualdad y el tono de piel en las Américas.” Proyecto de Opinión Pública de América Latina (2017): 1-11.

“If the confidence interval does not cross the vertical line at zero, the effect of skin tone is statistically significant with 95 percent confidence”. Zizumbo-Colunga and Flores (2017).

Survey questions in the range R3-R16.

Daniel Zizumbo-Colunga, and Iván Flores Martínez. “¿ Es México un país post-racial? La desigualdad y el tono de piel en las Américas.” Proyecto de Opinión Pública de América Latina (2017): 1-11.

On a personal note, I’m certain my own choices would skew my ranking on Z-CF’s material wealth scale. Microwave ovens (question R7) make you lazy and make you a worse cook. Seriously. No, seriously. I mean it.

Five countries have no 2016/17 data, so 2014 data was used instead: Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, Belize and Bahamas.

Gender, Ethnic identity, Urban vs rural.

The personal income scale does not increase monotonously.

Saint Kitts and Nevis had a p-value of 0.072, pretty close to significance, when not controlling for region.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Simpson%27s_paradox

p-value is a probability, so its value ranges from 0 to 1. Also notice the adjusted R-squared values, which indicate that the explanatory power of these models is limited. Personal income is not merely a function of years of education, gender, and place of residence. There’s likely a lot of noise.

Interesting original paper and even more interesting analysis by you, Javiero! Thank you.

An observation: The Caribbean includes many countries that were not included in this data set. For instance, the entire Dutch Caribbean (St. Maarten, Curacao, Aruba, and the special municipality islands of Bonaire, St. Eustatius, and Saba, and which I have an interest in since I live here) is not included. It's also the case that most of the Latin American and Caribbean countries that were included in this analysis have significant income inequality. The more unequal a country is overall, the easier it is going to be to statistically show differences between groups, but also the more that generational consolidation of wealth is going to affect incomes now.

So, for instance, Brazil has a Gini coefficient of 0.52, while my island home of Saba has a Gini coefficient of 0.35--lower than any of the countries included in this analysis. So I wonder about this effect of general income inequality making the effects of income inequality between groups more dramatic. Would we expect to see reduced impacts of skin color on income in places that have greater income equality overall?