He’s our son of a b*tch… but which one?

The Somozas, the Sandinistas, and liberation against...

You’ve probably heard the story about how, in 1939, U.S. president Franklin D. Roosevelt supposedly commented on Nicaragua’s president at the time: "Somoza may be a son of a bitch, but he's our son of a bitch." Although apocryphal, this anecdote still contains a kernel of truth in that it reflects the notion, held by some people within Latin America and beyond, of what constituted American foreign policy towards Latin America during the 20th century.

That policy is perceived as U.S. acceptance of any Latin American dictatorship as long as the dictator was friendly towards America, which, for most of the century, often entailed being against communism1.

I’m not going to argue against that notion. Numerous instances of American actions support the view that this was indeed American policy.

In this post, I aim to examine the idea that anti-American sentiment in Latin America was, at least partially, a response to the aforementioned U.S. foreign policy, whether Somoza in particular was a product of this policy, remaining in power through the active support of America, and whether the Sandinista guerilla (FSLN) was a reaction to Somoza’s despotic rule.

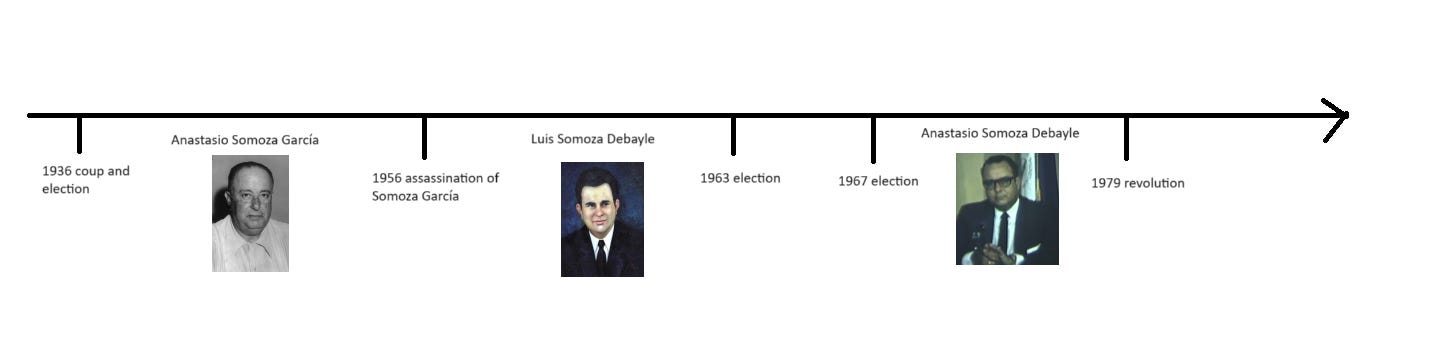

Let’s start with a bit of family history. The Somoza that Roosevelt supposedly mentioned was Anastasio Somoza García, who held sway over Nicaragua from 1936 until his assassination in 1956. He inaugurated a dynastic rule that would last for 43 years, carried on by his sons Luis Somoza Debayle and Anastasio Somoza Debayle.

To avoid any confusion2, I’ll use shortened forms when referring to the sons of Anastasio Somoza García, Luis and Anastasio. Luis Somoza Debayle will be Luis S.D. and Anastasio Somoza - the younger or little - Debayle will be A So the L. D., or ASol D. for short.

One significant fact worth noting is that the Somozas realized the convenience of occasionally letting someone loyal to them to assume the presidency, effectively delegating the daily governmental responsibilities. For instance, in the 1963 presidential election René Schick ran as the Nationalist Liberal Party (PLN) candidate3, and governed the country until his death on 3 August 1966, even though the Somoza brothers maintained paramount power. After Schick’s death, he was succeeded by Lorenzo Guerrero who completed the original term in May 1967.

Nicaraguan politics in the early 20th century was dominated by two major political factions, Liberals and Conservatives, with the former ones grouped around the aforementioned PLN4 and the latter around the Conservative Party. These parties not only embodied the traditional ideologies of classical liberalism and conservatism but also represented the interests of the elites of Nicaragua’s two main cities at the time, the liberal León and the conservative Granada.

Several years before becoming the big man of Nicaragua, in 1919, Somoza García married Salvadora Debayle, the niece of future liberal president Juan Bautista Sacasa, thereby aligning himself with the left-wing Nicaraguan politics of the time, which were represented by the Liberal Party.

He would go on to fight as a general for the liberal side in the 1926 rebellion against conservative general, and coup leader, Emiliano Chamorro. This rebellion culminated in a U.S.-mediated peace agreement between Liberals and Conservatives, paving the way for José María Moncada, a Liberal politician, to assume the presidency in January 1929, right on time to preside over the difficult years of the Great Depression.

Moncada's presidency was marked by a significant economic downturn, with Nicaragua's GDP experiencing a decline of approximately one-third. These catastrophic economic conditions persisted under his successor, Juan Bautista Sacasa, who was elected in 1932 and appointed his relative, Somoza García, as head of the Nicaraguan National Guard, a military force established to suppress the caudillo-led regional militias that had caused so much instability in Nicaragua during the preceding decade.

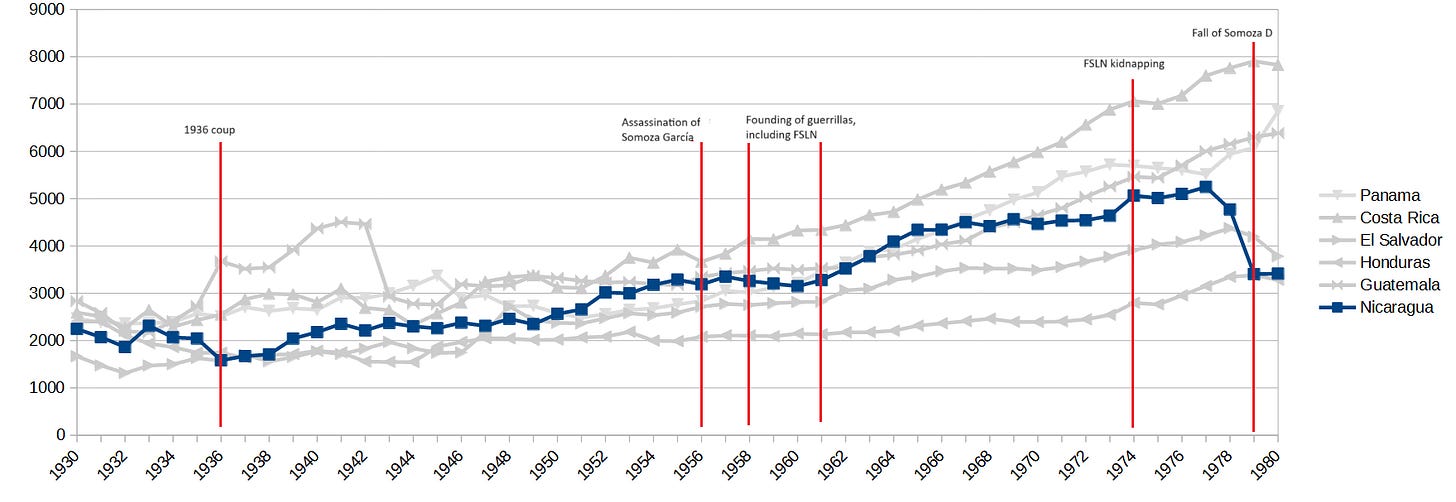

By the time Somoza executed his infamous 1936 coup, the first of two, Nicaragua’s per capita income was still more than 40% lower than what it had been before the Great Depression. Under those conditions and considering his rule over the National Guard it’s no surprise that Somoza was able to seize power in 1936.

But how did he manage to stay in power for the next 20 years?

The following chart comparing Nicaragua’s per capita income to those of its Central American neighbors might shed some light on that question.

You can see in the previous chart that during the rule of Somoza García (1936-1956), Nicaragua moved from the poor Central American countries group to the richer Central American countries group. The fact that income doubled during those 20 years might go a long way towards explaining why Somoza García managed to hold on to power for so long, without having to face much popular opposition to his government. In fact, he largely co-opted the Nicaraguan left and labor movements5:

after the assassination of Sandino on February 21, 1934, a part of the PTN [Partido Trabajador Nicaragüense] leadership began to slowly turn towards General Anastasio Somoza, who aiming to seize power, embraced a discourse in favor of the rights of workers and therefore “social justice”.6

And after seizing power, he continued his efforts to co-opt the labor movement for at least a decade or more. It’s revealing that during the massive demonstrations against Somoza García in June and July 1944, led by students and the newly formed Independent Liberal Party (PLI)7, the Nicaragua Socialist Party (PSN) opposed the demonstrations8, dismissing them as public order agitation.

The Nicaraguan right was also co-opted by Somoza García. As head of the National Liberal Party, he engaged in negotiations with the opposition Conservative Party, leading to a power-sharing agreement that granted Conservatives the role of official opposition in April 1950.

The agreement was known as the pact of the Generals because those who signed it were Somoza García as head of the liberals and General Emiliano Chamorro as head of the Conservative Party. Chamorro had led an insurrection against the regime in September 1947, which was a reaction to a previous May 1947 coup orchestrated by Somoza García.

Why did Somoza García execute a coup in May 1947, when he was already the paramount leader of the country?

Well, after a decade in power even Somoza García’s Liberal Party colleagues were growing weary of his leadership and wanted a different party candidate for the 1947 presidential election9. Somoza acquiesced but still leveraged his influence to select a malleable candidate, Dr. Leonardo Argüello. However, this maneuver backfired as soon as Argüello took office:

I will not be, by the way, a simple figurehead.

Somoza García took issue with this statement by Argüello and had him unceremoniously deposed and exiled.

The U.S. did not approve of the coup and withheld recognition of the new president, or more properly, the new figurehead president, Benjamín Lacayo Sacasa, and his successor Víctor Manuel Román y Reyes until May 194810.

After his “victory” in the May 1950 election, Somoza García found himself largely free from the concerns of having to deal with an organized opposition for the next few years11. Not coincidentally, this period was marked by a notable rise in per capita income, averaging an increase of 5% per year.

The Luis S.D. era

The year Somoza García was assassinated, 1956, Nicaragua entered a period of very low economic growth that persisted until 1961. During this period his sons Luis Somoza Debayle (Luis S.D.) and Anastasio Somoza Debayle would take the reins of the country, with the elder brother Luis assuming the presidency (1957-1963), while the younger brother Anastasio (ASol D) assumed as Chief of the National Guard.

By the time Luis S.D. left the presidency in the hands of René Schick12, Nicaragua was on its path to becoming the second wealthiest country in Central America13, and the Sandinista guerrilla - founded in 1961 but preceded by several revolutionary and guerrilla movements in 1958, 1959 and 1960 - was on its way to becoming irrelevant14.

After a couple of years of guerrilla activity, the National Guard got the upper hand on the Sandinistas:

Between 1963 and 1967 a policy of conciliation [by the FSLN] and working alongside the traditional left was carried out, but it did not obtain results. [The FSLN] made the most of those years to, on the other hand, carry out important experiences within the popular masses and ties with the poor peasantry.15

There wasn't much action. A few years later, things hadn’t improved for the Sandinistas:

In 1970, ... the FSLN launched the slogan of silently accumulating forces, reducing war actions to a minimum16.

From the fray of battle to launching slogans. The armed struggle can wait for a better time.

Coincidentally, according to the U.S. ambassador in Nicaragua, Luis S.D. was taking his job seriously17:

[Luis S.D.] takes his presidential duties seriously, listens to advice and does not make the same mistake twice. He is decentralizing the Government and giving his Cabinet Ministers and department heads increased authority and backing up their decisions. He has eliminated some of the rackets and is removing dead wood from Government payrolls. About one thousand employees have been dropped by the railroad alone. By eliminating the political hacks he plans on saving about three million dollars a year… In short, he has been cleaning house a little too rapidly which is not always politically wise, and as a result he will probably slow up the process temporarily

Luis S.D., apparently unaware of his role as right-wing Latin American dictator, even dabbled in communism:

The President and his Government continue to be friendly to the United States. The Foreign Minister and the Minister of Agriculture are quite nationalistic. They, along with several others, think a little bit of Communism would be a good thing because it would make the United States a little more liberal18

This little bit of communism might refer to Nicaragua’s limited land reform, started in 196419, with the founding of the Nicaraguan Agrarian Institute (IAN)20. A little bit of redistributionism never hurt anyone.

But then, at the same time as Nicaragua’s 1960s economic boom was winding down in 1967, Luis S.D. died due to a heart attack. His death left his younger brother, ASol D, who had recently won the presidential election, in charge of the country.

ASol D takes charge

Riding on the coattails of the 1960s economic boom, ASol D gained further approval from the Nicaraguan people by signing the abolition of the 1916 Bryan-Chamorro Treaty in July 1970. This treaty granted the U.S. full rights over any future canal built through Nicaragua, a condition widely perceived by Nicaraguans as infringing upon their sovereignty.

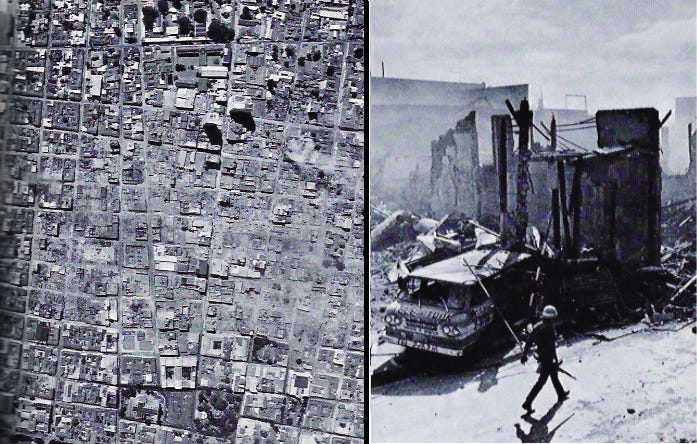

However, ASol D's fortunes would eventually decline. In addition to the lack of economic growth that characterized the period from 1967 to 1972, the 1972 Nicaragua earthquake struck a devastating blow, causing extensive damage and destruction to significant parts of the capital city, Managua.

The earthquake leveled large parts of the city, including several hospitals, fire stations, and the homes of hundreds of thousands of Nicaraguans.

The earthquake could not be blamed on the president, but the government response to the catastrophe was blamed on him. Despite substantial international aid, the reconstruction process was painfully slow, testing the patience of Managua's residents.

Countries such as Mexico, Costa Rica, Cuba, China, the Soviet Union, the United States, Spain, Japan, Venezuela, among others, joined in these humanitarian support efforts, sending rescuers and supplies21.

The sluggish pace of the process might have been influenced by the uncertainty among Nicaraguan leaders, including Somoza, regarding the wisdom of rebuilding the city in the same location.

In Somoza's opinion, it was necessary to look for another place that offered better guarantees, since the city was built between some thirteen volcanoes, which logically represented a constant danger.22

Ultimately, the downtown area of Managua was never fully reconstructed, and even today, a significant portion of the original downtown consists of parks, open spaces, and parking lots.

Whether due to corruption, incompetence or just lack of funding, the slow reconstruction and haphazard displacement of the downtown’s former residents generated further discontent with the regime.

Residents had long complained of the water stations interspersed throughout the neighbourhoods. When the government finally responded to their entreaties, it announced that the public water services would be removed and the residents would be charged to install taps in their homes. Riots broke out on the night of 7 October 1974. Residents destroyed the government-installed facilities.23

And Nicaraguan public opinion leaned towards the notion that their predicament was caused by corruption:

for example, Col. Rafael Adonis Largaespada, military aide-de-camp to General Somoza, paid $71,428 for a piece of land on June 4, 1975, and sold it to the Government for $3,342,000 on Sept. 24 of the same year. Such practices were exposed by an A.I.D. investigation, but the abuse of foreign assistance continued nonetheless.24

In addition to the earthquake’s aftereffects, ASol D’s government faced another challenge. The Somozas never enjoyed significant support from the Catholic Church, which was traditionally close to the right-wing conservative party, yet they also didn’t have to worry about the church actively denouncing their regimes.

This dynamic shifted with the ascent of ASol D. Under his rule, the Church, led by Managua Archbishop Miguel Obando y Bravo25, began to openly denounce the regime's political intolerance and escalating human rights violations.

This was particularly bad for Somoza due to the deeply religious nature of the Nicaraguan people and the close ties between the Nicaraguan clergy and many elite families.

In the aftermath of the earthquake, ASol D abandoned his latest half-hearted attempt to co-opt the political opposition. Although a triumvirate had ostensibly governed Nicaragua since May 197226, while Somoza remained as National Guard Chief, he circumvented the triumvirate and assumed the presidency of a newly established National Emergency Committee.

The next few years were marked by continued economic stagnation, increasing Sandinista activity - attacks on the National Guard, kidnappings, robberies, etc - and a devastated downtown Managua left to decay.

In October 1975, United States ambassador James Theberge described the situation in Nicaragua as follows27:

Sentiment in favor of the FSLN as the only active vehicle to challenge the regime seems to have grown in the past several weeks. This is generally attributed to the silencing of the overt opposition through censorship rendering it incapable of competing for the anti-government constituency. Overt opposition groups are experiencing grass roots pressures to cooperate with the FSLN as impatience among youth and unrest among campesinos makes itself felt… organized private sector sentiment has been muffled by timely GON28 concessions on energy rates and appointments to key government posts…the Church, has been silent and complacent encouraging the suspicion that Somoza has enticed it into an inoffensive posture through promises on Church reconstruction in Managua.

The final days

Until early 1978, ASol D had the support of the Nicaraguan business community, or at least he did not face significant opposition from it.

That situation changed in January 1978, following the assassination of Pedro Chamorro Cardenal, the owner and editor of Nicaragua's most widely circulated newspaper, La Prensa. Given that Chamorro Cardenal was a vocal critic of ASol D, his murder immediately raised suspicions of involvement by the Somoza regime.

Moreover, Chamorro Cardenal played a crucial role in the 1974 founding of the Unión Democrática de Liberación (UDEL), a political coalition that aimed to unify all peaceful opposition to Somoza - only to be eventually sidelined by the Sandinistas. His death marked a definitive break between the dictator and the Nicaraguan business community - shocked by the assassination of such a prominent business and political figure - whose leaders organized a 10-day business strike29, demonstrating their collective strength and capacity to exert pressure on Somoza.

After the assassination of Chamorro Cardenal, the days of the Somozas as supreme leaders of Nicaragua were counted. The Nicaraguan elite not only opposed ASol D politically, but also took up arms to challenge his rule.

The initial trickle of young Nicaraguans from elite families into the FSLN, a flow that had been going on for years, now became a torrent30. And the small, ineffective guerrilla grouping now became a growing and increasingly sophisticated movement.

By September 1978, the U.S. government was already preparing for the impending transition away from the Somoza regime:

Our preferred outcome is to see a moderate transitional government succeed General Somoza. While the Sandinistas, through the Group of 12, will no doubt participate in some form in this transitional government, our goal should be to try to isolate them and to minimize and to gradually reduce their influence. (If their influence is reduced gradually, that would permit the new government sufficient time to cohere, to gain the support of the Guardia, and to ultimately defeat the Sandinistas.)31

Eventually ASol D left Nicaragua in July 17, 1979, after writing a short resignation letter, leaving the country in the control of the Sandinistas. For weeks prior to his resignation, the FSLN - operating from its bases in Costa Rica and Honduras - had been steadily gaining ground, capturing city after city and closing in on Managua.

In July 19, 1979, the Sandinistas were welcomed into Managua as liberators by a population eager for change after years of devastation, economic stagnation, and, particularly in the final months of the Somoza regime, increasing physical violence.

I apologize for not providing more evidence in support of the argument I’m making (do read the footnotes please). This post is too brief to adequately explore all the material needed to substantiate my points effectively.

But I hope I have at least persuaded some of you of the following: the Sandinistas were not brought to power by a bottom-up rebellion of the Nicaraguan masses, driven by a longstanding aspiration for democracy.

The Nicaraguan revolution was led by young middle and upper-class Nicaraguans, who had no support from the popular classes until those impoverished Nicaraguans realized that Somoza was not capable of lifting them out of poverty. They did not support a leftist liberation movement against a supposed rightist dictatorship out of ideological conviction.

I plan to write a follow-up post that will enable me to explore this and other points in greater depth and breadth.

Costa Rica’s president, and one-time revolutionary, José Figueres commented on Central American dictatorships: “It seems that the United States is not interested in honest government down here, as long as a government is not communist and pays lip service to democracy.“

Confusing the different Somozas seems to be the most common mistake in casual conversations about Nicaragua’s history. It would be much simpler if they had short, distinct-sounding names like Kim Jong Un, Kim Jong Il, or Kim Il Sung. Or maybe just go regal with Anastasio I, Luis I, Anastasio II.

He won the election with an implausible 90.5% of votes.

It’s worth noting that the word Nacionalista was added to the PLN’s name in 1928, during the Constitutionalist War, which arose amidst the backdrop of the American occupation of Nicaragua. This war pitted the American-supported Conservative government against the Liberals, Somoza’s party. Nationalist should probably be interpreted as anti-American.

The PTN, Nicaraguan Labor Party, was the main party representing labor union interests in Nicaragua.

“3 de julio de 1944: fundación del Partido Socialista de Nicaragua (PSN)“, https://elsoca.org/index.php/america-central/movimiento-obrero-y-socialismo-en-centroamerica/5466-nicaragua-3-de-julio-de-1944-fundacion-del-partido-socialista-de-nicaragua-psn

Somoza García’s leadership within the Liberal Party was not absolute, and the PLI, formed by anti-Somozistas in the mid 1940s, would go on to compete against Somoza García in the 1947 election. The PLI not only survived the Somoza regime but also remained a relevant political force in Nicaragua up to the 21st century.

The PSN would only break with the Somoza regime in the 1960s, during the rule of Luis Somoza Debayle, when the party split on the issue of whether armed combat against the regime was justified or not.

The 1947 presidential election seems to have been comparatively less fraudulent than others, with the opposition candidate, Enoc Aguado, garnering 38% of the vote. This era of reconciliation to the Conservatives coincided with a distancing, and at times, suppression of the Nicaraguan far-left, partly motivated by a desire to align with the U.S. during a period of intense anti-communist policy.

See: https://history.state.gov/countries/nicaragua

See “Nicaragua: Elections and Events 1937-1970“, Social Sciences ad Humanities Library, UCSD, https://web.archive.org/web/20070709121820/http://sshl.ucsd.edu/collections/las/nicaragua/1937.html

This was not as straightforward as Luis S.D. simply appointing his “puppet” and everyone going along with his decision: “Internal animosity exploded into an open, ongoing controversy when Somoza announced his support for Foreign Minister René Schick as the Liberal candidate for president in January 1962…Many within Somoza’s administration took exception to the decision. An early front runner for the nomination, Minister of Government Julio Quintana, bitterly opposed Schick…Quintana threatened to take his supporters within the PLN to a floor fight at the party’s national convention in 1962”, Gambone 2001.

In 1965, Nicaragua was the seventh richest country in Latin America.

Those same years saw the conservative opposition revitalized, led by a new young leader, Fernando Agüero, and the creation of several new movements and parties.

See: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frente_Sandinista_de_Liberaci%C3%B3n_Nacional#Popularizaci%C3%B3n_del_FSLN

See: https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frente_Sandinista_de_Liberaci%C3%B3n_Nacional#Popularizaci%C3%B3n_del_FSLN

See “Despatch From the Ambassador in Nicaragua (Whelan) to the Department of State“, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1955-57v07/d115

See “Despatch From the Ambassador in Nicaragua (Whelan) to the Department of State“, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1955-57v07/d115

“In the period 1925-49, overall yields per area dropped continuously, and by 1957-58 the yield per tree or hectare in Nicaragua was 50% lower than Costa Rica or El Salvador. This changed by the 1950s.“, Johannes Wilm 2014, The Significance of the Agrarian reform in Nicaragua, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267153814_The_Significance_of_the_Agrarian_reform_in_Nicaragua

See: https://www.alainet.org/es/active/9714

See: https://proceso.com.do/2022/12/23/50-anos-del-terremoto-de-managua-uno-de-los-peores-desastres-de-la-historia-de-nicaragua/

See: https://www.prensalibre.com/hemeroteca/tragica-navidad-en-managua-nicaragua/

“De-centring Managua: post-earthquake reconstruction and revolution in Nicaragua“, David Johnson Lee 2015, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/urban-history/article/decentring-managua-postearthquake-reconstruction-and-revolution-in-nicaragua/A59112F3365B34D34D0A51B3D6932FA0#fn45

See: https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1978/07/30/110909196.pdf?pdf_redirect=true&ip=0

Later Cardinal Obando y Bravo. He would go on to openly support the Sandinista grab of power just before the fall of ASol D, then turn against the Sandinistas dictatorship once they assumed absolute power in the early 1980s, and finally support Sandinista leader Daniel Ortega’s return to power in the mid 2000s, in exchange for a ban on abortion in the country.

The negotiations that culminated in the Kupia Kumi Pact, ultimately resulting in the formation of the triumvirate government, began in November 1970. So ASol D got a good two years out of the patience, or naivety, of the Nicaraguan opposition. Fernando Agüero (see footnote 13) was part of that triumvirate until March 1, 1973, when he resigned realizing that the National Emergency Committee President was in full control of the country.

See “Telegram 3875 From the Embassy in Nicaragua to the Department of State“, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76ve11p1/d257

Government Of Nicaragua.

At its inception, the business strike was declared with no set end date, suggesting it might have been conceived as a strategy to pressure Somoza into resigning.

These children of elite families, by leveraging their high human capital, quickly ascended the ranks of the guerrilla. When the Sandinistas eventually seized power, some of them, including Chamorro Cardenal’s children Claudia and Carlos, secured high-ranking positions within the new government. Claudia became an ambassador and Carlos became the head of the main Sandinista newspaper.

Quote from “Memorandum From Robert Pastor of the National Security Council Staff to the President’s Assistant for National Security Affairs (Brzezinski) and the President’s Deputy Assistant for National Security Affairs (Aaron)“, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1977-80v15/d98

Fascinating. I had never known any of this history beyond a vague right-wing Somozas vs. left-wing Sandinistas, and it's very interesting to learn how wrong that impression of mine had been.

So...with that caveat that I'm real ignorant about all this, is the Pedro Chamorro Cardenal here the husband of President Violeta Chamorro?

Thank you for this very educational essay.