Haiti and the Dominican Republic

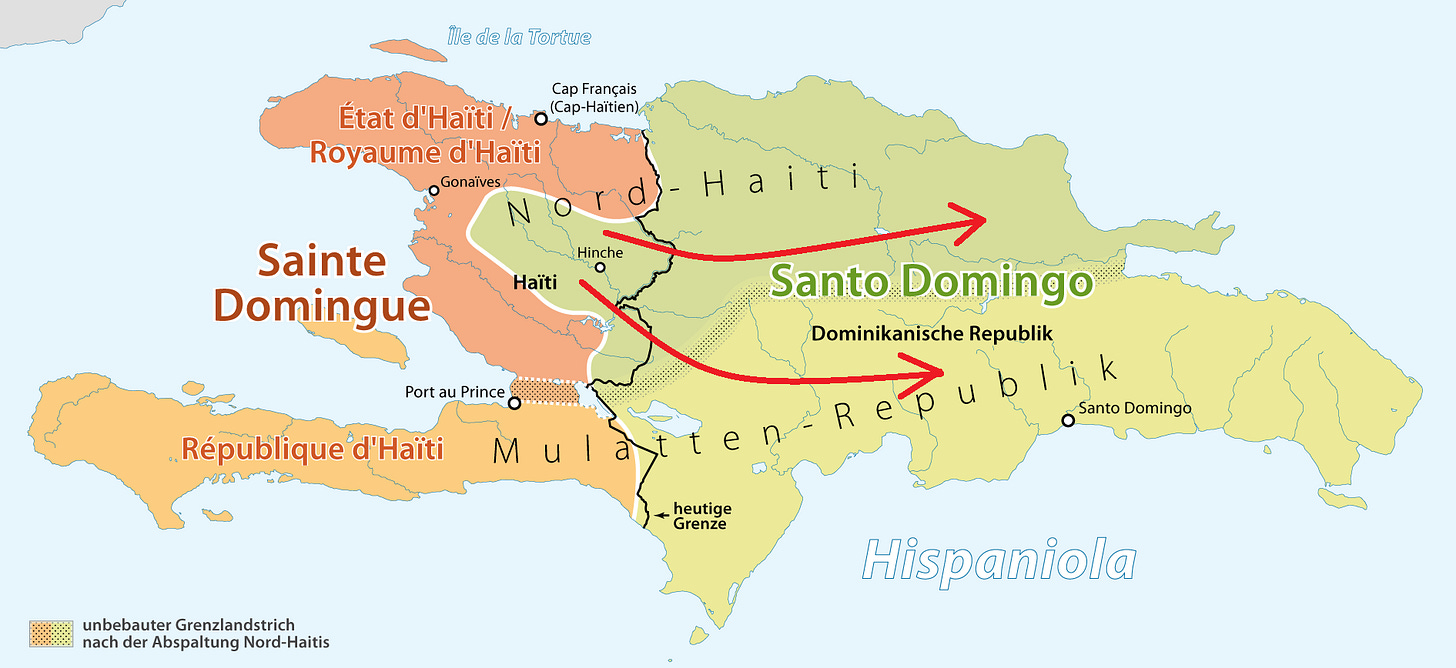

A comparison of immigration east and west of the border of Hispaniola Island

A puzzling phenomenon in the area of development economics is the enormous difference in human development between Haiti and the Dominican Republic, two countries which share the same island, have similar populations, share many elements of culture and history in common, and yet have such a large disparity in wealth between them. The Dominican Republic’s GDP per capita PPP is more than 10 times higher than Haiti’s.

In this post I’ll try to shed some light on a topic not often discussed when trying to explain how these two countries have reached such different economic outcomes in the less than two centuries since their splitting apart.

I will not go into too much detail concerning very important events in Haitian and Dominican history unless they have a bearing in the history of immigration for both countries, so you might want to brush-up on the history of both countries if you feel like you need more context.

Arguably the most successful slave rebellion in the history of the world was the Haitian Revolution of 1791. The rebellion ended French rule in what had been until that time the very rich colony of Saint-Domingue, and it’s abolition of slavery was followed by a successful defense of the freedoms the former slaves had won, eventually leading to the massacre of almost the entire remaining population of white French people on Haiti.

I’ll spare you the gory details about the massacre but I will quote a couple of paragraphs from Wikipedia that might help to understand its effect in the long term.

The course of the massacre showed an almost identical pattern in every city [Dessalines] visited. Before his arrival, there were only a few killings, despite his orders. When Dessalines arrived, he first spoke about the atrocities committed by former French authorities, such as Rochambeau and Leclerc, after which he demanded that his orders about mass killings of the area's French population be carried out.

This allowed certain categories of whites to be excluded from massacre… select male Frenchmen; and a group of medical doctors and professionals. Reportedly, also people with connections to Haitian notables were spared. In the 1805 constitution that declared all its citizens as black, it specifically mentions the naturalizations of German and Polish peoples enacted by the government, as being exempt from Article XII that prohibited whites (“non-Haitians;” foreigners) from owning land.

I would dare say that the local population in each Haitian city not only hesitated to kill the local white population owing to their sense of human decency but also knew how useful they might be as medics, administrators, etc…

The effect of the massacre from a demographic point of view was small. Only 3,000 to 5,000 white people were killed out of a total Haitian population of more than half a million. Most of the 40,000 white people living in Haiti before the 1791 rebellion had already left the island, fled to the Spanish side of the island (Santo Domingo), or had been killed during the rebellion and the bloody and ruinous attempts by the French, British and Spanish to reconquer Haiti.

But the effect in terms of how the rest of the world saw Haiti was probably large. Any European or white person who might have considered settling in Haiti to exploit the island’s exceptional conditions for growing coffee and sugar probably thought better of it.

It probably also made legal restrictions in the settling of foreigners in Haiti easier to enforce. Most early Haitian constitutions made it clear that whites were not welcome and could not own property in the island, and even by 1843 long after Haiti had obtained recognition as an independent nation and regularly traded with the rest of the world whites were not allowed to acquire Haitian citizenship or own property in Haiti.

Eventually, some foreigners seem to have tried to settle in Haiti as evinced by this passage from Jacques Nicolas Léger’s Haiti: Her History and Her Detractors.

Until Geffrard's advent the foreigners in Haiti, whilst enjoying the greatest protection, were subjected to many restrictions; thus they were not allowed to marry the natives. On the 18th of October, 1860, a law was enacted authorizing such marriages.

Yet even after obtaining the right to marry Haitians, foreigners still could not become Haitian nationals themselves. The naturalization of foreigners only became possible in 1889 and owning property as a white foreigner only during the United States occupation of Haiti (1915 - 1934).

Meanwhile… east of the border

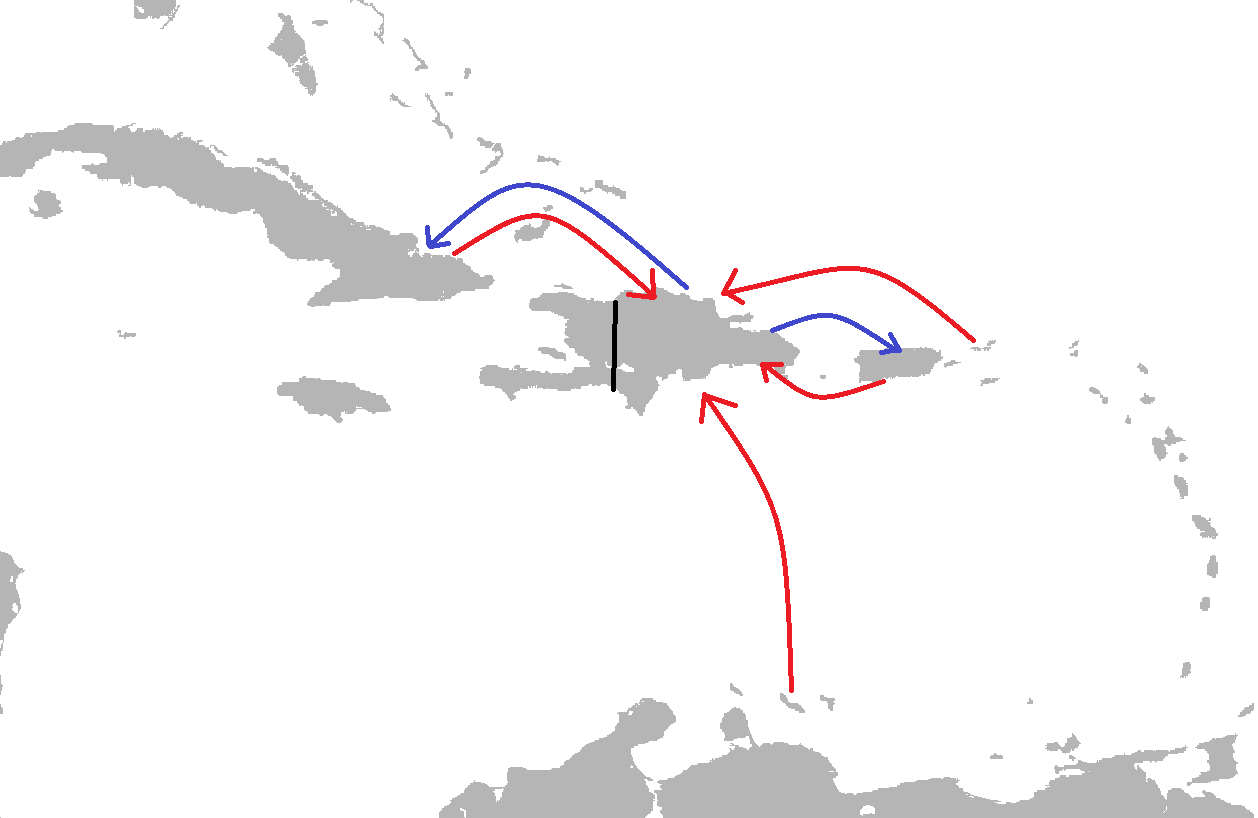

In the meantime in the Spanish half of the island people were on the move, fleeing from the chaos of the Haitian rebellion and the subsequent European and Haitian invasions. While Haitians were closing off their country not just to the French but other Europeans, Spanish Dominicans were moving to Puerto Rico or to Cuba and then returning to Santo Domingo when things calmed down. A temporary calm that meant the return of the Spanish as nominal rulers of Santo Domingo and so its reintegration into the world economy during the España Boba period.

Also internal migration was a factor in shaping the population of the future Dominican Republic due to the migration of those who lived in the westernmost part of Spanish Santo Domingo, and thus more exposed to the troubles of western Saint-Domingue, to the safer lands to their east.

That area, centered in the town of Hincha (nowadays Hinche) accounted for close to 14% of the population of Santo Domingo at the time and so many descendants of these migrants where among the later generations of Dominicans.

After having dealt with internal migration, welcoming French Saint-Domingue refugees and also Dominican refugees returning from Cuba and Puerto Rico it’s no wonder that when Santo Domingo recovered its independence, after the Haitian occupation of 1821 - 1844, nationality was defined in a very loose way.

The Dominican Constitution of 1844 did not define nationality or citizenship, but rather specified that Dominicans were people born in the territory, Spanish citizens who had Dominican parents and descendants born abroad to ancestors of the territory. All three classifications, required establishing residence in the country. It also allowed foreigners married to Dominican women to become Dominican after a three-year residency period.

Even before Santo Domingo achieved its independence as the Dominican Republic in 1844 a few immigrants had already made it their home and more would come after independence. Some of them were French like general José María Imbert who fought many battles against Haiti or Furcy Fondeur who would went on to fight in the Dominican Restoration War as a colonel.

Many came from small sugar producing Caribbean islands like Curaçao (doctor, politician and educator Francisco Henríquez y Carvajal’s father) and Denmark’s Saint Thomas (future three-time president Ulises_Heureaux’s mother, and future president Carlos Morales Languasco’s father) looking for opportunities in the sparsely populated Dominican Republic where land was plentiful and the sugar industry was in its infancy.

By the 1860’s even Italians were arriving in the DR to try their luck in the sugar industry:

Juan Bautista Vicini Canepa, was born in 1847, in Zoagli, a coastal village near Genoa. Vicini left Italy and went to the Dominican Republic in 1860 at the age of 12 . He was invited to travel to the Dominican Republic as an apprentice to join his countryman Nicole Genevaro who was an exporter of coffee and sugar. After a few years, he purchased the operations belonging to Mr. Genevaro.

Juan Bautista, better known as "Baciccia", was very successful in business. Thanks in part to his hard work and his savings, he managed to acquire land for the cultivation of sugar cane.

Eleven children were born of his marriage to Mercedes Laura Perdomo Santamaría. Seven of them went to live with her to Genoa, Italy. While being married, he had an affair with María Burgos Brito and begat 3 children, among them, President Juan Bautista Vicini Burgos.

Also, immigrants from English speaking Caribbean islands began settling the Dominican Republic’s northern coast in the middle 1800s and were so numerous by the end of the century that they received their own appellation, Cocolos, which also became associated with their culture:

The first Turks and Caicos Islander immigrants began arriving in Puerto Plata after the Dominican War of Restoration, long before the modern sugar industry was established. There were carpenters, blacksmiths and schoolteachers who emigrated due to the economic crisis in the Bahamas and Turks and Caicos. Many also came as stevedores on the Clyde Steamship Company boat line, which dominated trade for many years. When the railroad of Puerto Plata-Santiago was built in the late 19th century, many came from these islands to work on the railroad as well as others from Saint Thomas, which was then a Danish colony.

The Dominican War of Restoration by the way was fought at the end of the Spanish re-annexation of 1861–1865 after Dominican president Pedro Santana asked the Spanish back (yes, I’m no longer a colony but I would like to be a colony again is a thing) prompted to a large extent by the fear of new Haitian invasion. Thousands of Spanish citizens arrived into what was then the Captaincy General of Santo Domingo - effectively a part of Spain - either to trade, serve in the Spanish army, serve in the local bureaucracy or just to try their luck in the new world.

And many of those Spaniards remained in the island once it became the Dominican Republic again, among them one José Trujillo Monagas, a sergeant from the Spanish Canary Islands who would be the grandfather of the infamous dictator, ladies’ man and unabashed collector of medals Rafael Leónidas Trujillo.

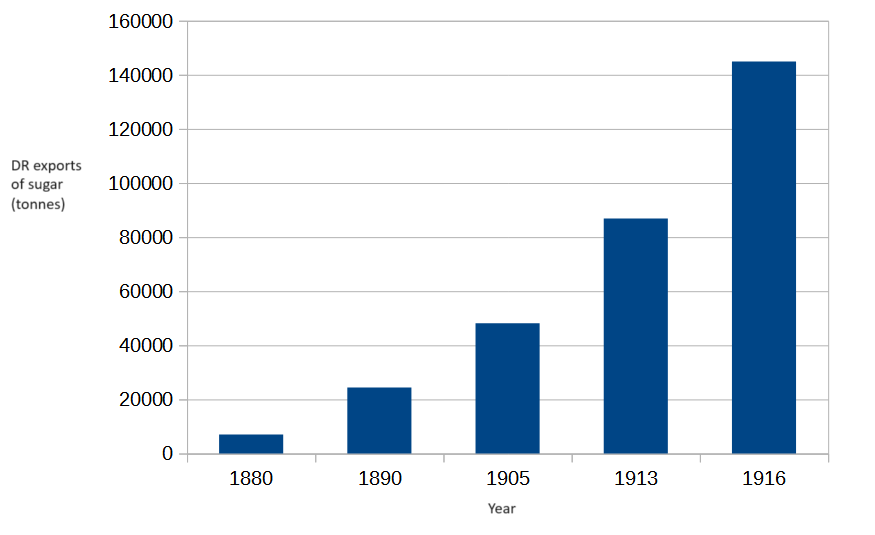

Some of those immigrants not only were attracted to the sweet wealth that the Dominican Republic was beginning to produce but actively participated in the process of generating that wealth, with sugar exports climbing from 7,000 tonnes in 1880 to 24,352 tonnes in 1905 and 144,911 tonnes in 1916, the first year of the United States’ occupation.

By contrast, Haiti did not export any sugar at the beginning of the 20th century.

From the middle east to the east side

Another source of immigration during the last decades of the 19th century was the Eastern Mediterranean, especially Lebanon which was the birthplace of José Sesin Abinader who after emigrating to the Dominican Republic in 1898 and marrying a Dominican-born daughter of Lebanese immigrants became the father of businessman and three-time presidential candidate José Rafael Abinader Wassaf. And where Abinader Wassaf failed his son Luis Abinader Corona succeeded. Abinader Corona is the current president of the Dominican Republic (elected in 2020).

By contrast on the other side of the border there seems to be little chance that Haiti will join the long list of Latin American countries which have had a president of Arab descent:

But before he can even test his platform, Mourra, a Haitian of Arab descent, will first have to get on the ballot.

“Haiti is a black country and should be led by a black person,“ said Herntz Phanord, a Miami-based Creole-language radio personality who has been raising the issue of race on his popular call-in show on WLQY-AM (1320).

Like many Haitians, Phanord has strong views about Haitian Arabs, believing they have not done enough for Haiti. He said he respects Mourra's right as a Haitian to run for president but hopes “he doesn't make it.“

Mourra said such opinions are divisive and hamper Haiti's progress. Not only does he believe the country is ready for a nonblack leader, but he believes he has the support of public opinion behind him.

And those bad feelings towards Arab Haitians are not new, having a precedent already in the early 1900’s. In fact they seem to have arisen soon after the arrival of Arabs into Haiti.

[President Leconte] pursued a discriminatory policy toward the local Syrian population… Prior to ascending to the presidency, he had promised to rid Haiti of its Syrian population. In 1912 Leconte's foreign minister released a statement stating that it was "necessary to protect nationals against the disloyal competition of the Easterner whose nationality is uncertain." A 1903 law (aimed specifically at Syrians) limiting the immigration levels and commercial activities of foreigners was revived, and the harassment of Syrians that had been prevalent in the first few years of the 1900s was resumed. When Leconte died suddenly in 1912, a number of Syrians celebrated his passing and were imprisoned as a result, while others were deported.

If you want more details on this episode, the New York Times Times Machine is at your service.

Migration into the DR from all those different sources was not massive but it was high enough that a 5.5% share of the Dominican population in the year 1920 was foreign-born, though only 2.4% of the population were non-Haitian immigrants. A share of 2.4% of the population may not seem like much, but it’s comparable to the figures for other Latin American countries at the time: 0.78% for Mexico in 1921; 3.2% for Chile in 1920; 4.7% for Costa Rica in 1927.

By contrast migration into Haiti seems to have been very low. I couldn’t find any data on the foreign-born population of Haiti during the first decades of the 20th century (only a dubious claim of 15,000 Syrians and a less dubious one of 500) but judging by the legal hurdles in place for immigrating to Haiti and the very few notable 19th or 20th century Haitians who have foreign ancestors the numbers were never large.

In fact it’s very telling that the two noteworthy Haitians in politics who descend from immigrants have a black Caribbean ancestor, though in contrast to immigrants to the DR they are immigrants from French speaking or Creole speaking islands. These are president Paul Magloire (1950-56), whose grandfather Jean-Jacques Magloire immigrated from Dominica (the Commonwealth of Dominica, not the DR), and Haiti’s own infamous dictator François Duvalier, whose father Duval Duvalier immigrated from Martinique.

This fact attests to the meager number of immigrants to Haiti, even those of African ancestry that were allowed to settle in Haiti without difficulties, and also to the enormous success those few immigrants achieved in Haiti.

The 20th century

Haiti and the DR were not immune to the decrease in migration flows experienced by most countries in the Americas after the first couple of decades of the 20th century. And in the case of the DR it implemented its first restrictive measure in 1912 by demanding a permit for potential immigrants from Asia, Africa, Oceania and the French and British islands of the Caribbean.

Haiti on the other hand seems to have taken the opposite route and decided to relax some rules regarding naturalization of foreigners, starting with a 1902 treaty with the US on naturalization. This might be related to the fact that the US was becoming the most important and influential foreign power in Haiti eventually occupying Haiti for 19 years (1915 - 1934). Like I mentioned before, it was only during said occupation that owning property as a white foreigner was finally allowed in Haiti.

Does this mean Haiti and the DR were finally converging in their immigration policies during those years?

Hardly.

We must also not forget that policies and regulations do not guarantee the desired results. In 1860 the Haitian government headed by Fabre Geffrard promulgated a law promoting the immigration of persons of African and Indian race into Haiti, but the absence of a population of Indian ancestry in today’s Haiti should make it clear the law failed in its purpose.

Around the same time this law was being published, faced with a lack of labor to develop the sugar industries of its Caribbean and Indic colonies the French government also decided to promote the immigration of Indian laborers to those colonies. Yet France didn’t just enact a law but had to actually sign an agreement with the colonial power controlling India at the time, Britain, and put in place a relatively complex organizational structure in order to reach its objective.

On 25th July 1860, a Franco-British agreement was signed, authorising an initial recruitment of 6,000 Indians destined for Reunion. On 1st August 1861, this agreement was extended to France’s other sugar-producing colonies, with no limit in numbers: these agreements provided the terms and conditions for Anglo-Indians immigrants, all the way from the recruitment process to the details of everyday life. In exchange, a British Consul was appointed in order to ensure that these contracts were respected and to manage any complaints from the indentured workers.

And the results of this organizational structure speak for themselves. Between 15% to 25% of the current population of Reunion descends from Indian immigrants while Indo-Guadeloupeans constitute around 10% of the population of Guadeloupe.

It’s fair to say that the Haitian government did make a serious attempt at organizing a successful immigration scheme in 1824 under president Jean-Pierre Boyer, who coincidentally anticipated many of Geffrard’s policies, by promoting the resettling of thousands of free African Americans to Haiti. In this case the Haitian government recruited the settlers, paid their full passage to Haiti and distributed land for them so settle in.

Ironically even this one successful immigration scheme did not ultimately benefit Haiti but the Dominican Republic. During president Boyer’s rule Santo Domingo was under Haitian occupation, and since the eastern half of the island was sparsely populated compared to the western half it seemed reasonable to give land to the African American settlers in the eastern half, what would become the DR. And so the approximately 6,000 immigrants settled in Samaná, and after the Dominican Republic achieved independence they became citizens of this new nation.

It would seem that at least some of the first heads of government of Haiti did understand the consequences of closing off to the world, including Toussaint Louverture who not only preceded Boyer and Geffrard but is usually considered as the Father of Haiti.

They strongly disagreed about accepting the return of the white planters who had fled Saint-Domingue at the start of the revolution. To the ideologically motivated Sonthonax, they were potential counter-revolutionaries who had fled the liberating force of the French Revolution and were forbidden from returning to the colony under pain of death. Louverture on the other hand saw them as wealth generators who could restore the commercial viability of the colony. The planters political and familial connections to Metropolitan France could also foster better diplomatic and economic ties to Europe.

In summer 1797, Louverture authorized the return of Bayon de Libertat, the former overseer of the Bréda plantation, with whom he had shared a close relationship with ever since he was enslaved. Sonthonax wrote to Louverture threatening him with prosecution and ordering him to get de Libertat off the island. Louverture went over his head and wrote to the French Directoire directly for permission for de Libertat to stay.

Haiti’s closing off to immigration was apparently a gradual process that took several decades to arise.

I’ll take them all

By the 1950’s and 60’s the DR was catching up with Haiti in terms of population density and that meant less opportunities for enterprising immigrants who might want to make a future for themselves in the agricultural sector. Land was not so abundant anymore and even though sugar production was still climbing (300,000 tonnes in 1925, and 550,000 tonnes in the 1950s) that increase mostly hinged on mechanization and cheap labor, not an appealing prospect for most migrants.

Thinking of migration as a push-pull phenomenon, the pull towards the DR was not so strong anymore while the push was also getting weaker in the DR’s traditional sources of immigrants.

But the push was not completely gone. The mid-20th century had a large enough number of wars and genocides that millions of people were pushed to look for a safe haven far away from their home countries.

In 1939, with the end of the Spanish civil war hundreds of thousands of Spanish Republicans went into exile crossing the French border only to be locked in concentration camps at the other side. And with the start of the Second World War the need to find a new home, preferably outside of Europe, reached a new urgency for many of them.

Latin America seemed like a logical destination for these refugees but their ideological bent meant that many Latin American countries - the ones ruled by right leaning governments at the time - did not want them, while those who where receptive (Chile, Mexico) put restrictions in the number of refugees they were willing to accept. But not the Dominican Republic, already headed by Trujillo at the time, who welcomed as many Spanish Republicans as wanted to settle in the DR. And many did take Trujillo up on his offer. Communists, Basque nationalists, Trotskyists, Anarchists, all of them were welcome in the DR.

This openness to migrants was in line with the DR’s attitude towards Jews shown during the 1938 Evian conference when Trujillo offered to accept up to 100,000 Jewish refugees, offering them land to settle in the town of Sosúa.

Even though less than 1,000 Jewish refugees eventually settled in the DR, it’s estimated that approximately 5,000 Dominican visas were actually issued for Jewish refugees during the Second World War.

Even Hungarians were welcome in the DR (1956).

Even Japanese were welcome in the DR (1956).

And ironically, when Trujillo’s regime finally ended with his assassination in 1961, one of the plotters involved in the assassination was an immigrant recruited by the Trujillo regime due to his skills.

De Ovín Filpo who was born in Spain, arrived in the Dominican Republic in 1954 from Madrid, hired by the Trujillo regime to work in the State Sugar Council (CEA), being named director of said Council on two occasions.

Should we include Manuel De Ovín Filpo in the list of very successful Dominican immigrants?

While Trujillo was trying to attract anyone who would come to the DR, including people who would criticize and oppose his regime, Duvalier in Haiti was doing the opposite1. Between 1957 (the start of the Duvalier regime) and 1963, 6,800 Haitians entered the US with an immigrant visa while another 27,300 entered with a temporary visa. Between 1964 - when Duvalier declares himself president for life - and 1971 the American immigration services record the entry of 140,000 Haitian immigrants. Many of them were not escaping poverty.

When talking about immigrants and descendants of immigrants to Haiti or the Dominican Republic I’ve mostly focused on politicians as a group that is easy to inquire into, and I’ve left aside other groups such as businessmen and artists. I don’t think that omission negates this analysis, and the only comment I would be compelled to make when looking at other groups is to remark on the relatively large Arab Haitian (and Sephardic Haitian) business community. This again proves how enormously successful Haitians of an immigrant background have been, and is a subject that I plan to discuss in a future post comparing the development of the Haitian and Dominican economies.

Just to make sure I wasn’t unintentionally cherry picking the successful Dominican and Haitian politicians I’ve already mentioned, I went through the whole list of Dominican and Haitian heads of government for the 20th and 21th century. 43% of the 28 Dominican heads of government had an immigrant background, meaning at least one immigrant parent or grandparent. While in the case of Haiti only three heads of government (8%) during the same period of time had an immigrant background.

It’s not my place to make policy suggestions for Haiti, but a clear and honest understanding of the roots of Haiti’s problems would go a long way towards improving the lives of average Haitians. Even today Haiti is one of only two sovereign countries in the Americas that does not apply the principle of jus soli in its nationality law2, meaning being born in its territory is not enough to acquire Haitian nationality.

While the DR has seized every opportunity to welcome immigrants who could contribute to its development and prosperity, Haiti has shut its doors to those who could have helped in creating a better present for all Haitians.

To end on a happy note, I focused on heads of government as examples of successful politicians and successful people in general, but I could have widened my criteria by including mayors of Santo Domingo (the DR’s capital), presidential candidates or leaders of major political parties.

José Francisco Peña Gómez was all of those things. From his Wikipedia page:

Born to María Marcelin, a Haitian woman, and Oguís Vincent, a Haitian immigrant, on March 6, 1937, in Mao, Dominican Republic, Peña Gómez was adopted as an infant by Simón Pichardo and Andrea Rodríguez de Pichardo, a Dominican family, when his parents had to flee to Haiti (where they died) in order to save their lives as the Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo enacted the Parsley Massacre against Haitians that same year.

Yes, even Haitian immigrants can succeed in the Dominican Republic.

You can read the follow-up to this post, focusing on education in the DR and Haiti, here.

Not exactly at the same time. Trujillo’s regime lasted from 1930 to 1961, while the Duvaliers’ regime lasted from 1957 to 1986.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Haitian_nationality_and_citizenship. The other country is The Bahamas.

So I know I'm real late to this party but I just found this piece of yours.

As a proud immigrant to Saba, an island that has a very high percentage of immigrants (~40% of the adult population, here defined as being born outside of the Dutch Caribbean) and also that did the whole, "hey, can we be a colony again?" thing, I found this history extremely interesting. Thank you for your work on it!

On openness to immigrants and also colonizers, maybe, the themes seen here with Haiti and DR reminded me a kind of similar findings Rasheed Griffith writes about, here:

https://cpsi.media/p/colonialism-and-progress-fb9