Did Fidel Castro spoil the party?

Was 1950’s Cuba an (almost) developed country?

Describing 1950s Cuba as a party might seem exaggerated, but I’ve encountered numerous times the claim that the Cuban Revolution not only halted Cuba's economic development but significantly reversed it, causing the country to lose out on several decades of economic growth that had previously placed it as a leader among Latin American nations in terms of development.

In my search for a quotable version of this assertion - a precise and clear claim by a respectable author1- I found this 2016 post by economic historian Bradford DeLong2:

Under Fidel Castro it looks as though Cuba lost two generations of economic growth--generations that other neighboring economies like Mexico, Costa Rica, and Puerto Rico made very good use of. The only good thing you can say about Castro is that Cuba continued to have the social indicators of a middle-income country even as it became a poor one.

I agree that Mexico and Costa Rica seem like good candidates for comparison with Cuba.

A truly remarkable number of well-intentioned people in comments who have not done their homework. They look at Cuba today, and say: "Look at how good its social indicators are for a poor country!" But Cuba back in 1957 was not a poor country.

Was it a middle-income country maybe?

The hideously depressing thing is that Cuba under Batista--Cuba in 1957--was a developed country. Cuba in 1957 had lower infant mortality than France, Belgium, West Germany, Israel, Japan, Austria, Italy, Spain, and Portugal. Cuba in 1957 had doctors and nurses: as many doctors and nurses per capita as the Netherlands, and more than Britain or Finland. Cuba in 1957 had as many vehicles per capita as Uruguay, Italy, or Portugal. Cuba in 1957 had 45 TVs per 1000 people--fifth highest in the world. Cuba today has fewer telephones per capita than it had TVs in 1957.

I assume DeLong’s claim is not that Cuba in 1957 was already a developed country by the standards of 2024. Rather, I understand his claim as: Cuba’s income, consumption patterns and health indicators in 1957 were similar enough to those of developed nations at that time to justify describing Cuba as developed during the late 1950s.

In his own words:

You take a look at the standard Human Development Indicator variables--GDP per capita, infant mortality, education--and you try to throw together an HDI for Cuba in the late 1950s, and you come out in the range of Japan, Ireland, Italy, Spain, Israel…given where Cuba was in 1957 [today] we ought to be talking about how it is as developed as Italy or Spain.

My first issue with DeLong’s statement is that he seems to imply that Cuba was (almost?) the most developed Latin American country in 19573. Yet four other Latin American countries - Argentina, Chile, Uruguay and Venezuela - had a higher per capita income at the time. Should we then conclude that all these four countries were also developed?

I don't think Chile and Venezuela were developed countries in the late 1950s by any means, and Argentina and Uruguay had already partially completed their 20th century transition from being rich countries to middle-income countries.

If Cuba was the fifth most developed country in Latin America, out of 19 countries, is that developed enough to be considered “almost” developed? What about seventh out of 19? Or eighth?

To answer those questions I read the papers cited by DeLong - “The Cuban sugar industry 1959–2019: from front-runner to back of the pack“ by Jorge F. Pérez-López (2019) and “Renaisssance and Decay: A Comparison of Socioeconomic Indicators in Pre-Castro and Current-Day Cuba“ by Hugo Llorens and Kirby Smith (1998) - along with some of the sources referenced in those papers, and a few others, in order to examine whether late 1950s Cuba could be considered a developed country.

What do the social indicators actually say?

Two of the most frequently cited sources by Llorens and Smith are the United Nations Statistical Yearbooks and Demographic Yearbooks. These sources provide a wide range of statistics, including those mentioned by DeLong on telephones, TVs, and vehicles per capita, as well as data on housing, public finances, trade, and many other subjects.

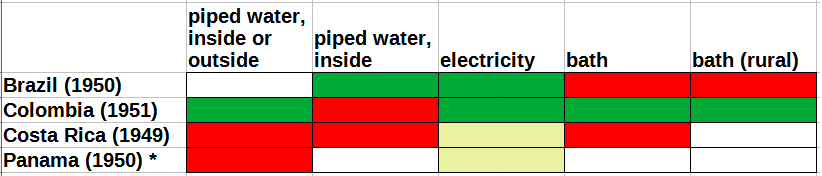

Let’s start with housing. This is how Cuba compares to four other countries4 on five dwelling attributes according the 1959 Statistical Yearbook.

Judging by the Statistical Yearbook data, in terms of urban housing, Costa Rica and Panama appear to be on par with Cuba, if not more developed, while Brazil and Colombia don’t seem to be that far behind.

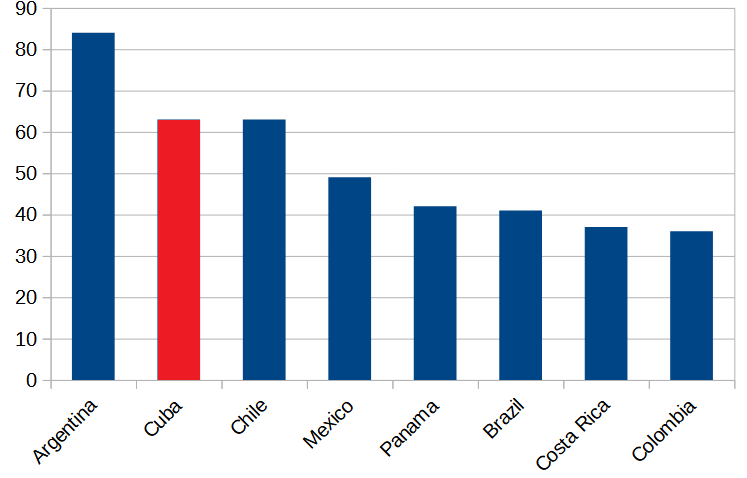

What about radios and television sets?

Cuba had the highest ratio of television sets per capita in Latin America, due to being the first country in the region to adopt television. From Wikipedia:

Cuba was the first Latin American country to begin television testing in December 1946… The first regular commercial broadcasting began in October 1950…In 1958, Cuba was the second country in the world (after the United States) to begin color broadcasting…Luckily Cuban broadcasting coincided with a glut of sets in the US market. Despite the high cost… the Cuban government's Imports and Exports Analysis Agency estimated that Cubans had imported more than 100,000 television receivers by 1952.5

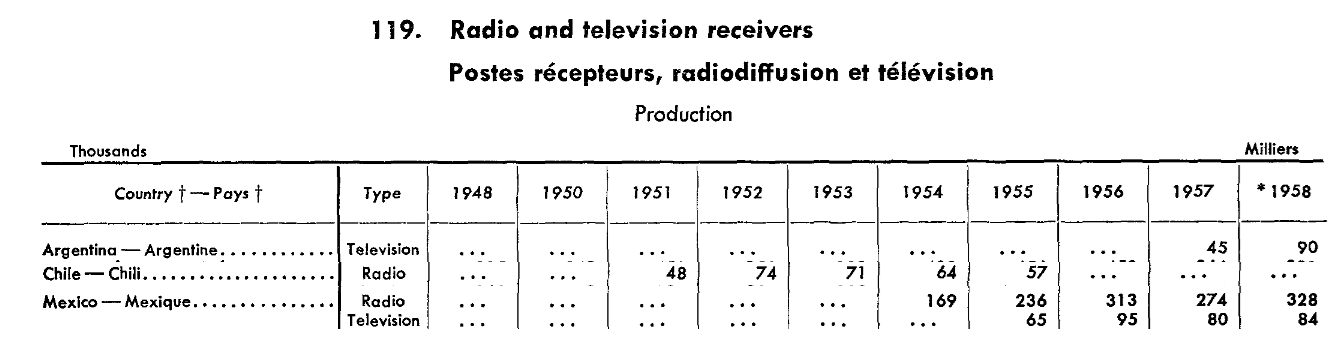

Incidentally, while Cuba was a large consumer of radios and television sets, other Latin American countries were producers of these devices:

Which is a more accurate indicator of a country's development: the ability to use the latest gadgets or the ability to produce them?

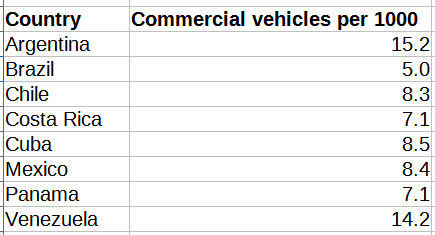

Examining the figures for vehicles per capita presents a similar dilemma. Should we focus on the ratio for passenger cars, possibly boosted by Cuba’s free trade regime with the United States, or on the ratio for commercial vehicles, which may more accurately reflect the overall level of economic activity?

This is the rate of commercial vehicles per 1,000 population for selected Latin American countries:

Cuba fares well compared to Chile, one of the four countries with a higher income, in this metric. However, it shows no difference compared to Mexico and just a 20% higher rate compared to Costa Rica and Panama.

What about consumption of basic industrial inputs?

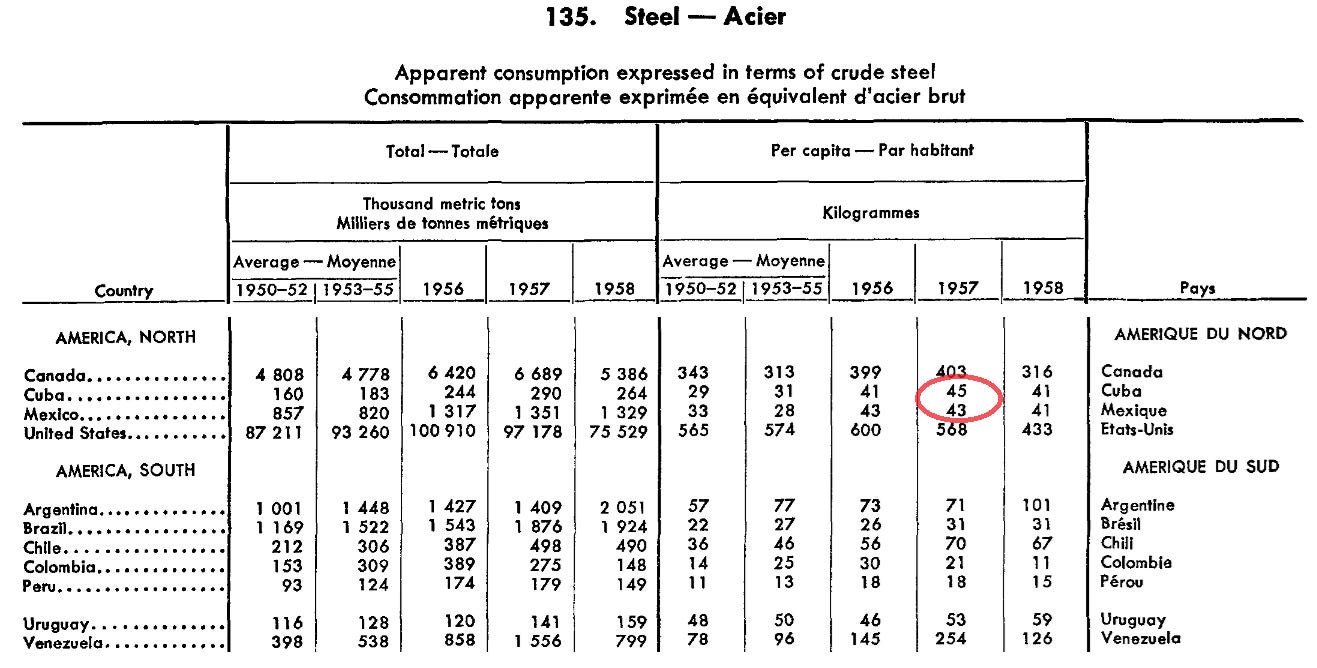

Cuban per capita consumption of steel was nearly on par with that of Mexico:

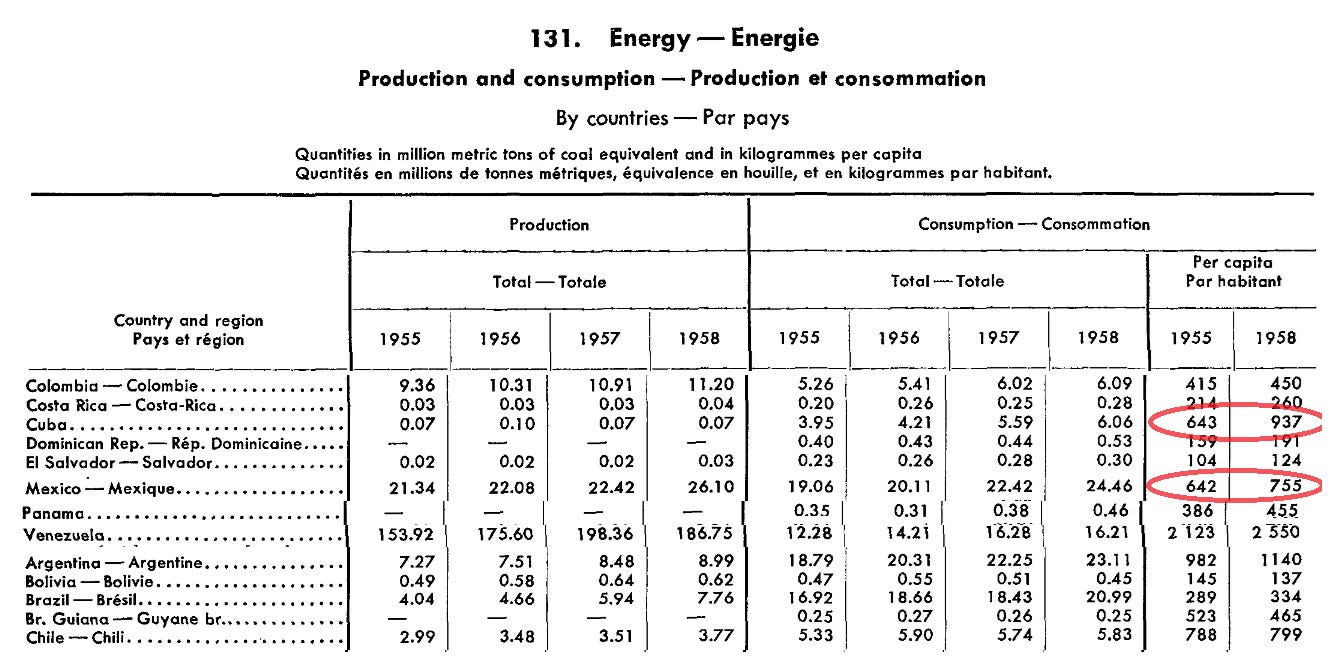

Per capita energy consumption, which had been on par with Mexico in the mid-1950s, briefly exceeded that of Mexico in 19576. This was only temporary, as Mexico again surpassed Cuba in 1961:

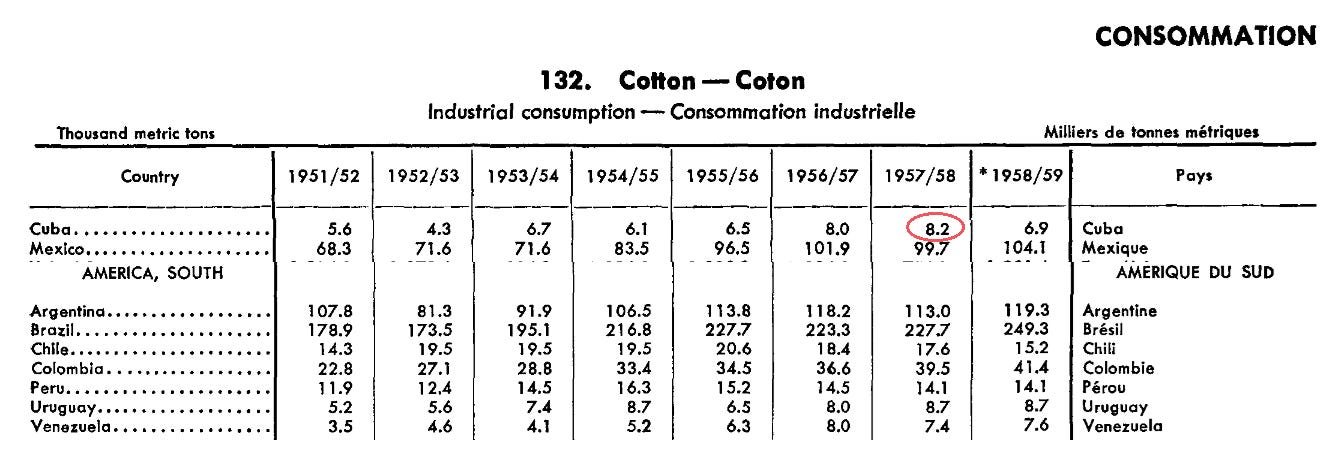

Industrial consumption of cotton, a crucial indicator of the development level of the textile industry, was much lower in Cuba7 than in Mexico, Colombia and Peru:

Also, the per capita industrial consumption of tin in Cuba was significantly lower than that in Mexico and Brazil.8

To summarize, based on the 1959 UN Statistical Yearbook, consumption of all industrial inputs for which there is data suggests that Mexico was a more developed country than Cuba.9

Healthcare indicators

DeLong’s observation regarding Cuba's remarkably low infant mortality rate comes from Llorens and Smith10:

Cuba’s infant mortality rate of 32 per 1,000 live births in 1957 was the lowest in Latin America and the 13th lowest in the world, according to UN data.

I first thought that the figure of 32 per 1,000 live births might come from the Statistical Yearbook, but after reviewing the relevant table (“Infant mortality rate“, page 47) I couldn’t find the infant mortality data for Cuba.11

Next, I tried the 1959 Demographic Yearbook’s table on "Infant deaths and infant mortality rates" (table 28), and again couldn’t find the rates for Cuba12. In fact, Cuba is the only Latin American country for which data was missing in that year’s table.

Then I tried the “Vital statistics rates“ table in the same yearbook. No luck.13

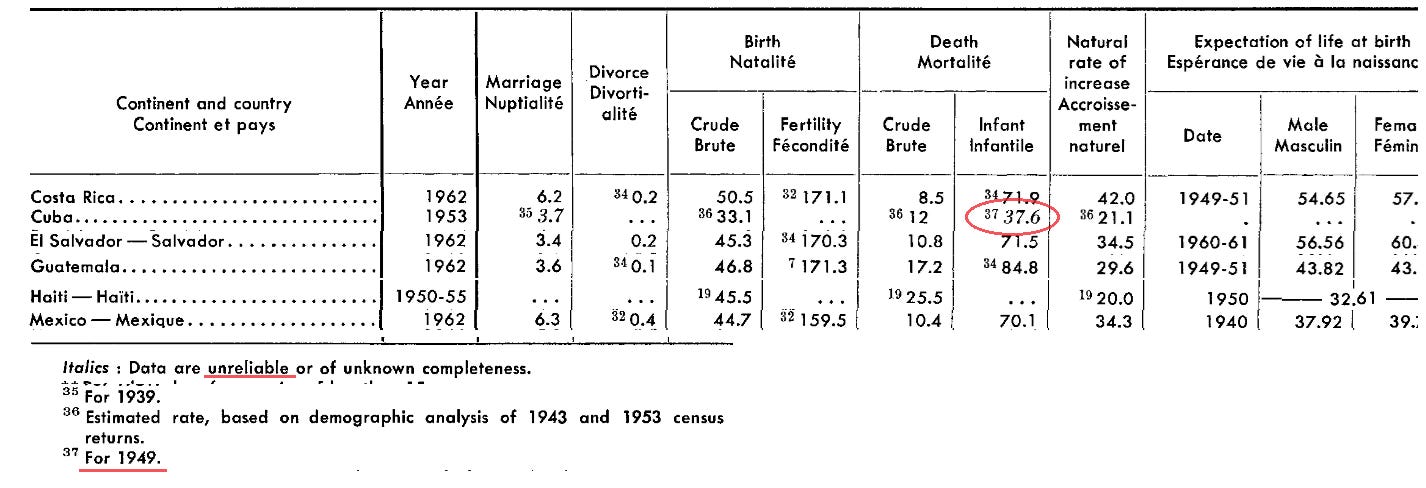

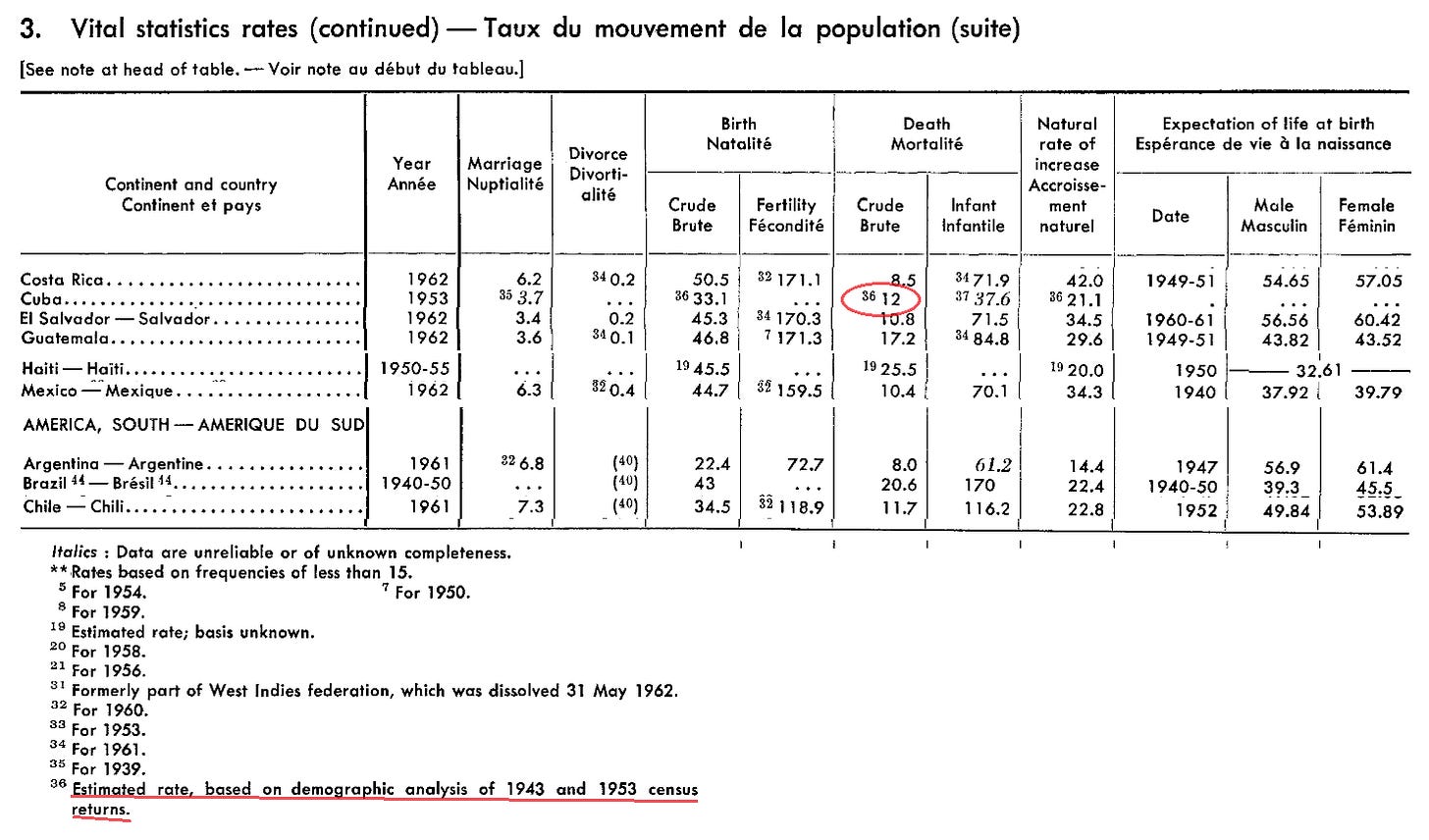

I finally was able to find an infant mortality rate for Cuba in the 1962 Demographic Yearbook’s table on “Vital statistics rates“ (page 141). The figure was 37.6 deaths per 1,000 live births:

That is a different number than the one given by Llorens and Smith, though the discrepancy could be explained by the fact that their data is from 1957, while the number I found is for the year 1949.

After some more digging, I found another rate in the 1962 yearbook’s “Infant deaths and infant mortality rates“ table. This time it was 38.9 deaths per 1,000 live births, specifically for the period from 1945 to 1949.

These numbers suggest a moderate improvement, from a range of 37-40 deaths in the 1940s to a rate of 32 in the late 1950s. At first sight, that seems plausible.

Except, those figures in the 32-40 range are very unreliable and not comparable to the rates for other Latin American countries. I’ve added the relevant footnotes to the previous screenshot, which mention the 1949 rate is unreliable:

Despite its unreliability, a rate of 37.6 is strikingly low. Maybe Cuba’s infant mortality was very low, even if it was not the 13th lowest in the world?

Not really. Allow me to show you a screenshot of the “Infant deaths and infant mortality rates“ table, including its footnotes:

Not only is the 38.9 death rate declared as unreliable, but we now have an explanation for the marvelous Cuban rate: the rate was calculated excluding live-born infants dying within 24 hours of birth. The only rate Cuba reported to the United Nations can’t be compared to other countries’ rate, and is significantly lower than the real infant mortality rate.14

Notice also that, in contrast to Cuba, the death rates for Costa Rica, El Salvador Guatemala and Mexico are reliable and available for all the years in the 1950-1961 range.

Lacking reliable 1950s infant mortality figures that can be directly compared to those of other Latin American countries, what alternative data can we gather that would allow us to evaluate and compare Cuba’s healthcare system?

My first choice would have been life expectancy data. Yet there’s no life expectancy data for Cuba in the two relevant tables of the 1962 Demographic Yearbook.15

Next, I decided to try with crude death rate data. Although this data is missing for Cuba in the Statistical Yearbooks, I did find it in two Demographic Yearbooks’ tables.

The data in the first table suffers from the same issues as the infant mortality rate. It’s specified as unreliable and also excludes deaths of infants dying within 24 hours of birth.

The data in the second table - “Vital statistics rates“16- is an estimate derived from Cuban censuses. Although not precise, it is nonetheless somewhat reliable:

The rate is 12 deaths per 1,000 population. It's important to note that this rate cannot be directly compared to those of other Latin American countries, as seen in the screenshot. This is because most of those countries had healthcare systems that were able to report basic data in a timely manner. You would be comparing Cuba's 1953 rate to other countries' 1961 or 1962 death rates.

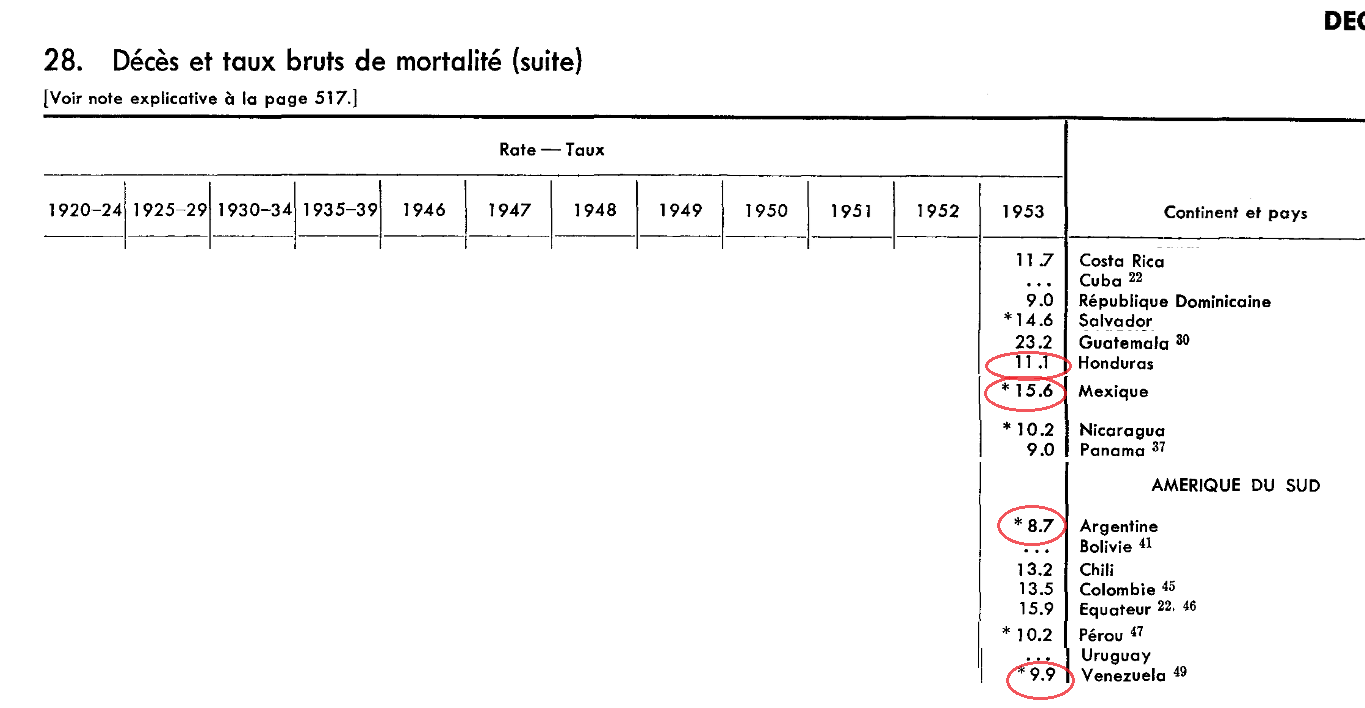

To obtain the comparable 1953 rates, I had to consult the 1954 Demographic Yearbook. These are the death rates I found (I have highlighted the ones declared as reliable):

Considering these numbers, and the fact that Costa Rica’s 1953 rate (11.7 deaths per 1,000 population) would seem to be reliable based on the 1962 yearbook17, Cuba does not have a particularly good or bad crude death rate.

Cuba certainly looks better than Mexico, yet by the late 1950s Mexico’s rate was already in the 11-13 deaths per 1,000 range - a significant improvement - while Cuba’s healthcare system wasn’t even capable of reporting its death rate.

Havana is not Cuba

I believe the data I’ve provided demonstrates that the quality of Cuban housing, industrial development and even healthcare were not exceptional in the 1950s. In fact, they were close to the median development level of Latin American countries at the time.

But there’s a clear objection that could be raised regarding one of the indicators I’ve presented. I’ve shown that housing quality was likely better in Costa Rica and Panama, compared to Cuba, for urban dwellings.

That is not the same as saying that Cuban housing quality was worse for all dwellings. Did I cheat?

Well, yes and no. I’m comparing apples to apples, not apples to oranges. The problem is, Cuba had a very high apples to oranges ratio during the 1950s. Cuba was highly urbanized compared to other Latin American countries, with close to 20% of its population living in Havana.

To a large extent, the illusion of Cuba's reasonably good economic and social indicators is primarily a result of its high urbanization rate:18

Providing electricity, running water, healthcare and education19 is easier when the population is concentrated in urban areas.

This might seem like a moot point when discussing the exact level of development of 1950s Cuba, but it’s very important when analyzing Cuba’s potential and why it didn’t live up to that potential during the next decades (recall “we ought to be talking about how it is as developed as Italy or Spain“).

Cuba had already progressed considerably towards urbanization, and its potential for further economic growth through increased urbanization was lower than that of most Latin American countries.

In conclusion, based on the data, Havana appears to have been a relatively developed city in the 1950s, but Cuba was definitely a poor country.

You can find many more versions of this claim by doing a few online searches. Many results will likely include images of well-dressed Cubans, enjoying what appears like a middle-class lifestyle.

This is not what Llorens and Smith say.

I excluded Argentina, Chile, Uruguay and Venezuela because we already know they had a higher income than Cuba. I excluded Mexico for lack of urban dwellings data. Didn’t consider one other dwelling attribute (gas) because there was no data for Cuba. Didn’t consider rural dwellings, with one exception, because there was no data for the other four countries.

Coincidentally, Cuban fertility declined sharply during the mid-1950s.

This might be related to the fact that construction of Cuba's first steelworks, Antillana de Acero, commenced in 1957.

Cuba seems to have had only one major textile factory at that time: Textilera Ariguanabo.

Table 136 of the 1959 UN Statistical Yearbook.

In 1956, Cuba’s per capita consumption of cement was also lower than that of Colombia and Mexico.

See Llorens and Smith (1998), “Renaisssance and Decay: A Comparison of Socioeconomic Indicators in Pre-Castro and Current-Day Cuba“, https://ascecubadatabase.org/asce_proceedings/renaisssance-and-decay-a-comparison-of-socioeconomic-indicators-in-pre-castro-and-current-day-cuba/

I found 1959 data for Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Chile and Uruguay. I also tried the 1962 Statistical Yearbook with no success.

I found data (1949 to 1958) for Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela.

I found data for Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Uruguay and Venezuela in this table.

The United Nations also collected and published perinatal mortality data in certain years. Yet the 1961 UN Demographic Yearbook does not have perinatal mortality data for Cuba (years 1952 to 1960), while it includes this data for Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico and Panama.

The tables are: “Expectation of life“ and “Vital statistics rates“. Recall that Cuba is notably absent from those tables in the 1959 yearbook.

Only for the 1962 yearbook. Cuba is again missing in the table for the 1959 yearbook.

Based on the 1962 yearbook, we should probably consider Costa Rica’s rate as reliable and Hondura’s rate as unreliable.

Especially beyond the primary level.

Fascinating analysis. Thank you!