Brazil, Uruguay and imperialist interventions in 20th century Latin America

Hegemons don't like messy neighbors

I apologize for the long hiatus; personal commitments kept me busy over the last few weeks.

I return with an account of a little known episode in South American history, one that I hope will illuminate dynamics between Latin American countries and their interactions with so called American imperialism.

It’s early 1970s Latin America. Revolution is in the air. The triumph of the 1959 Cuban Revolution ignited a wave of movements across the continent, each aiming to overthrow what they perceived as oppressive regimes perpetuating an unfair economic system, and fight what they saw as colonialist practices imposed by imperial powers. Either by peaceful means or by violent means.

The small South American country of Uruguay was no stranger to this phenomenon, and in 1962 a coalition of politicians and political parties, chief among them the Uruguayan Communist Party, established the Liberation Leftist Front, better known in Uruguay by its acronym FIDEL1. Yes, like that Fidel.

The following year, in 1963, the Uruguayan political landscape was further transformed with the emergence of the Tupamaros2, a new armed group championing a far-left anti-imperialist ideology. This group began its operations by stealing weapons from shooting ranges and armories, and explosives from stone quarries3. Once sufficiently armed, they launched a series of targeted attacks against their perceived enemies, including business leaders, police officers, and American corporations.

Despite Uruguay's established democracy and a long period of political stability, the social climate - mirroring much of Latin America - provided fertile ground for the emergence of this armed group, with severe economic turmoil, fierce labor disputes, frequent student protests and annual inflation rates exceeding 50%4.

Meanwhile, in Brazil, Uruguay's northern neighbor, the broader Latin American wave of armed insurgency was embodied by groups like the Palmares Armed Revolutionary Vanguard, MR8 and National Liberation Action, all of them with the stated purpose of toppling the military dictatorship that seized power in 1964, and enacting a revolution.

Whether in Uruguay, Brazil, Argentina or other countries, far-left armed groups intent on overthrowing the existing states faced similar challenges, chief among them the opposition from the local state security forces, which were trying to defeat them.

This alignment of goals and challenges, coupled with the aim to maximize their collective impact across different countries, led them to coordinate their efforts through entities such as OLAS, the Latin American Solidarity Organization, established in 1967:5

The Communist Parties were aligned at two extremes; on the one hand were those of Argentina and Brazil, considered right-wing deviationists, who supported the need for political work within the masses, using legal means and rejecting the possibility of violent insurrection. On the other hand, there was the inclination towards armed struggle promoted by the Cubans, an action that was chosen by the Uruguayan communists, led by Rodney Arismendi who in turn was elected vice president of OLAS, while the Presidency was awarded to the then [Chilean] Senator Salvador Allende.

[At the] First Conference of the Latin American Organization of Solidarity (OLAS), in Havana, where hundreds of attendees signed a Declaration that said, among other things:

— That it is a right and a duty of the peoples of Latin America to make the revolution. (...)

- That the essential content of the revolution in Latin America is given by its confrontation with imperialism and the oligarchies of bourgeois and landowners. Consequently, the character of the revolution is that of the struggle for national independence, emancipation of the oligarchies and the socialist path for its full economic and social development.

- That the principles of Marxism-Leninism guide the revolutionary movement in Latin America.

- That the armed revolutionary struggle constitutes the fundamental line of the revolution in Latin America.

- That all other forms of struggle must serve and not delay the development of the fundamental line that is the armed struggle.”

By 1967, the Tupamaros had cemented their presence in Uruguay, gaining notoriety through a series of bombings and robberies that thrust them into the spotlight.

For the average Uruguayan citizen, these subversive activities likely blended into the broader backdrop of the widespread unrest that characterized Uruguay in the late 1960s.

During this period, instances of public violence grew increasingly frequent:6

On May 9 [1968], barricades are set up at crucial points in the city using burning tires. In each episode, both police and protesters are injured. The public banks go on strike. Eight days later, a student rally takes place at the University, which ends with serious riots. Tear gas is used. Three police officers are injured, two hundred people are arrested, and numerous shops are damaged.

The escalation of violence prompted a severe crackdown from the Uruguayan state, highlighting the inadequacies in police training and equipment for handling violent protests and organized subversive activities.

Luckily for Uruguay’s police force, the United States had established a program of cooperation, the Office of Public Safety (OPS)7, through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), providing training, assistance and equipment to law enforcement agencies across many countries.

Kidnapping the agent of the empire

In 1969, the OPS mission in Uruguay, which began in 1964, was taken over by Dan Mitrione, a former police chief of Richmond, Indiana. Mitrione had worked as an advisor to Brazilian police for seven years before being assigned to Uruguay.

Evidently, the establishment of the OPS office in Uruguay did little to foster goodwill among the Uruguayan far-left towards their perceived enemy. On July 31, 1970, barely more than a year since his arrival in Uruguay, Dan Mitrione was kidnapped by Tupamaros with the goal of exchanging him for 150 of their members imprisoned for earlier offenses in Uruguayan jails.

The same day Mitrione was kidnapped, Aloysio Dias Gomide, the Brazilian consul in Montevideo, Uruguay’s capital, was also kidnapped8.

At the time, the Uruguayan left’s view of Brazil was nearly as unfavorable as their already dim opinion of the United States. Uruguay’s northern neighbor had experienced its own wave of robberies and kidnappings by far-left groups, including the abduction of American Ambassador Charles Burke Elbrick in September 1969. This episode likely inspired the kidnappings of Mitrione and Dias Gomide, given that Brazil’s MR8 successfully traded the release of Elbrick for the release of 15 of its members.

In the words of A.J. Langguth, author of Hidden Terrors:9

They had chosen Dias Gomide much in the spirit that the MR-8 had Burke Elbrick, more for the country he represented than for anything in his background… For the last six years, Uruguayan liberals, even those with no admiration for the Tupamaros, had apprehensively watched the developments in Brazil. Arriving in Montevideo, their Brazilian friends would step from the plane and breathe deeply. “It’s wonderful,” they would say, “to be in a democracy again.”

Both, Mitrione and Dias Gomide, were targeted primarily for the countries they represented, rather than for anything in their personal backgrounds10.

The Uruguayan government refused to release the imprisoned Tupamaros or engage in negotiations with the far-left organization, leading to Mitrione's execution by his captors on August 10, 1970.

On the same day Mitrione’s body was discovered on the back seat of a stolen car, Uruguay’s President, Jorge Pacheco, secured the General Assembly's approval for a twenty-day suspension of individual rights, aimed at combating the ongoing insurgency11. There would be no negotiations with the Tupamaros.

Meanwhile, Dias Gomide remained in captivity. Following the Elbrick kidnapping and two subsequent abductions of diplomats12, both resulting in the release of armed group members, the Brazilian government revised its approach to managing such incidents.

The Brazilian state was now less inclined to yield to the kidnappers' demands:13

The [Uruguayan] government sends diplomatic notes to the United States and Brazil, trying to be understood in its firmness. There is no formal response, but its attitude is tacitly accepted. Even Vice-Chancellor Ricaldoni - as has already been explained - travels to Brazil to meet with Chancellor Gibson Barbosa, who formally maintains his claim, but informs him - confidentially - that the Armed Forces of his country are of the same opinion as the Uruguayan government. The Soviets are more clear in their support for the government, making public a favorable opinion.14

Ultimately, the consul’s wife raised a quarter of a million dollars and paid Tupamaros for the release of her husband, after 206 days of captivity15.

1971

The substantial shift in public opinion in the wake of Mitrione’s assassination, which now turned against Tupamaros16, did not deter the armed group. They continued their campaign of bombings, robberies, and assassinations into 1971, an election year17.

Finally, the Uruguayan government decided to involve the armed forces in the fight against the insurgency, deeming police efforts insufficient:18

The battle, until then, had been fought with the police, but less than three months before the election, the shock of the prison escape19 was psychologically too shocking: on September 9, 1971 (decree no. 566/971), the government entrusted the Armed Forces with the leadership of the anti-subversive struggle. It was a qualitative change in the situation, which the country had not yet fully grasped.

Ironically, this escalation by the government happened in a context of reduced violence by Tupamaros, because the armed group, in an effort to bolster the electoral prospects of the left-wing Broad Front coalition, declared a unilateral truce20.

But the truce only lasted until the electoral defeat of the Broad Front, which secured only 18% of the vote in the November election. Once their political ally was defeated in the polls, the Tupamaros resumed their attacks in February 197221.

The victor of the 1971 election, who replaced President Jorge Pacheco, was fellow Colorado Party politician Juan María Bordaberry. It was this same Bordaberry who would later execute a self-coup in June 1973, thereby establishing a civic-military22 dictatorship in Uruguay.

To invade or not to invade?

Up to this point, I’ve provided a very brief summary of Uruguay’s 1960s left-wing armed subversion leading up to the 1973 coup, which delivered the final blow to the Tupamaros. The Uruguayan armed group was not very different from other Latin American insurgencies of the mid-20th century, and the subsequent military dictatorship23 was no less harsh than other Latin American military dictatorships of that era.

What was very unusual was that this episode of Uruguay’s history nearly resulted in the country’s invasion - an extraordinary event considering that, despite the occasional saber rattling, invasions and wars between Latin American countries have been very rare in the past century.

I should also clarify that the perception you might have formed of Uruguay’s political and social climate at that time is not necessarily the same that Uruguayans - and Brazilians - held during that period. The perception of Tupamaros during the late 1960s in Uruguay - whether they were viewed as part of the problem or part of the solution to the prevailing crisis - has been muddled by the political success of former Tupamaros in the 21st century.

At the time, Tupamaros not only persuaded a considerable segment of Uruguay’s elites that their violent route to revolution had substantial support within the country, but they also managed to instill the same belief among many in Brazil.

In the words of Julio María Sanguinetti, Uruguay's first president following the restoration of democracy after the 1973-1985 dictatorship:24

The [Tupamaros] support for the Broad Front - then being formed - was expressed in a public declaration made in December 1970, in which it reiterated the conviction that "the oppressed will conquer power only through armed struggle", since it presumed that "the oligarchy" would not passively hand over the government if it lost the election.

The electoral appearance of the Broad Front changed the landscape of the campaign. Its militancy displayed an unprecedented dynamism and even its final act, on the wide Agraciada Avenue, made its supporters conceive the hope of a victory. There was a climate of euphoria in the leftist groups, which for the first time visualized the possibility of coming to power.

The Brazilian military dictatorship, having nearly eradicated its domestic insurgency by late 1971, was keen to prevent any resurgence, especially one that might be bolstered by a hostile Uruguayan government:25

The Brazilian government was apprehensive about the possibility that the "Broad Front", a coalition of leftist factions, would take power. The authorities, especially the military, were paying attention to the attitude of the numerous Brazilians exiled in the neighboring country and to the large leftist rallies and gatherings that were taking place along our border.

For years, the extent to which the Brazilian government would go to prevent a far-left victory in Uruguay remained unclear. Until, in January 2007, retired Army General Ruy de Paula Couto revealed the details:26

President Jorge Pacheco Areco himself asked Brazil for military aid, offering the possibility of invading Uruguayan territory if the Broad Front won the 1971 elections, according to what retired Brazilian Army general Ruy de Paula Couto said on a television program in Porto Alegre last night.

The Brazilian armed forces anticipated minimal resistance for their planned invasion. In fact, their Uruguayan counterparts had already agreed to cooperate with the intended occupation:27

The agreement meant that the Uruguayan Army would begin sending officers to be trained in Porto Alegre and to make contact with the Brazilian officers belonging to the powerful Third Army, in charge of the invasion. "We were not going to fight with the Uruguayan Army, but there would be an understanding between the two that they would operate in a joint action," said the military officer.

And the objective of the invasion was the suppression of what the Brazilian army perceived as the Tupamaros' near control over Uruguay:28

"I participated in the preparation of 'Operation Charrúa'. We were going to 'invade' Uruguay, almost in the hands of the Tupamaros. The vibe was so great among us that it seemed like we were living a great moment. 'Operation Charrúa' was not launched because the Uruguayans decided to solve the problem through the ballot box"

Even though the invasion never took place, Brazil's planned occupation of Uruguay in 1971 - forestalled by the decisive electoral defeat of Uruguay's Broad Front - underscores the extent to which Brazil, though no longer an empire, was prepared to exert its influence as the regional hegemon to preserve the stability of its periphery.

Throughout history, it's not unusual for larger nations to intervene in the affairs of their smaller neighbors, a pattern often motivated more by pragmatic interests than by ideological reasons.

Focusing on the United States' role as an imperial power might obscure the potential benefits that come from a larger power using its greater state capacity for the betterment of smaller nations.

The Tupamaros focused on a cause popular among the populace: challenging what they perceived as the imperialism from the distant and culturally alien nation of the United States, while overlooking the imperialistic tendencies of their neighboring country, Brazil.

A childish and futile endeavor.

National Liberation Movement – Tupamaros (MLN-T)

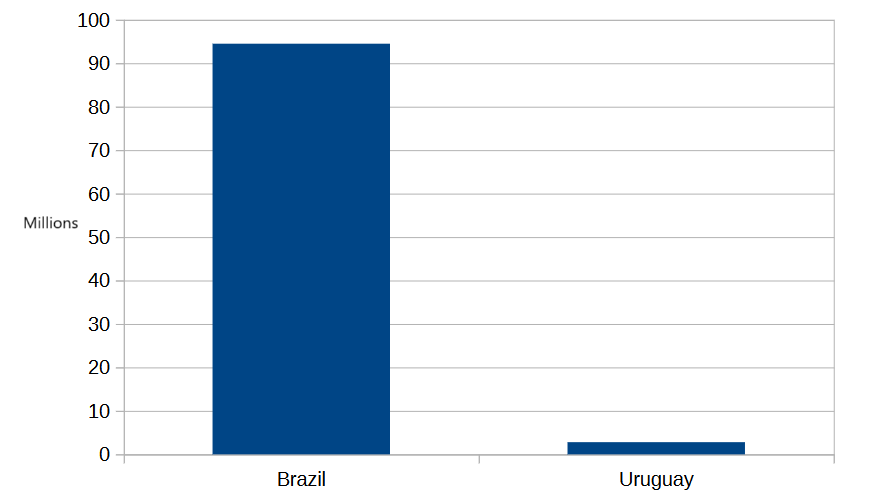

The fact that Uruguay is a small country, with a population of less than 3 million people at the time, surrounded by his larger neighbors Argentina and Brazil, both of which had a semi-autarchic economic policy of import substitution during the 1960s, contributed to its economic challenges.

“OLAS de 1967: la legitimación de la vía armada en Argentina, Chile y el Continente.“ and “La voluntad: una historia de la militancia revolucionaria en la Argentina”, Anguita Eduardo Y Caparros Martin, page 124.

“La agonía de una democracia: proceso de la caída de las instituciones en el Uruguay (1963-1973)”, Sanguinetti, Julio María, page 87.

I’m not going to provide a link to Wikipedia’s article on the Office of Public Safety. It’s filled with errors, distortions and inconsistencies, rendering it largely useless.

Gordon Jones, an American embassy officer, was kidnapped on the same morning as Mitrione and Dias Gomide, but he managed to escape from his captors. Additionally, Daniel Pereira Manelli, a judge, had been kidnapped on July 28, and Claude Fly, an agronomist working for USAID was kidnapped while Mitrione was still in captivity, on August 7. See “El caso Mitrione”, Clara Aldrighi, page 327.

“Hidden Terrors“, A.J. Langguth. Page 257.

Though in Mitrione's case, his captors apparently suspected he might be working for the CIA.

“La agonía de una democracia“, Julio María Sanguinetti. Page 66.

These were the abduction of Nobuo Okushi, the Japanese consul in Sao Paulo, on March 1, 1970, and the kidnapping of Ehrenfried Von Holleben, the German Ambassador, on June 11, 1970.

Later that year, when the Palmares Armed Revolutionary Vanguard (VPR) abducted Giovanni Bucher, the Swiss Ambassador to Brazil, the Brazilian government outright rejected the list of 70 prisoners presented by the armed group, and offered an alternative list of 70 prisoners to be released.

“La agonía de una democracia“, Julio María Sanguinetti. Page 173.

“Hidden Terrors“, A.J. Langguth. Page 286.

“La agonía de una democracia“, Julio María Sanguinetti. Page 169.

“La agonía de una democracia“, Julio María Sanguinetti. Page 216.

He is making reference to the prison escape from Punta Carretas Prison, on September 6.

“Los orígenes del Movimiento de Independientes 26 de Marzo”, Manuel Martínez Ruesta, pages 154 and 157.

It’s usually considered as a civic-military dictatorship because it involved significant civilian participation in the government, including the presidency, which was held by civilians for much of the period.

After dispensing with elections in 1976, the civic-military dictatorship became less and less civic and more and more military, with a former army general assuming as President in September 1981.

“La agonía de una democracia“, Julio María Sanguinetti. Page 230.

“À Sombra da Impunidade”, Dickson M. Grael. page 9.

“OPERACIÓN 30 HORAS”. Brazilian lieutenant Marco Pollo Giordani, cited by UY PRESS.