America as an early 20th century Central American policeman

Judging American interventions in Central America by their results

In the wake of the Spanish American wars of independence, the former Central American colonies of Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua and Costa Rica formed the Federal Republic of Central America1, but internal strife and power struggles led to its dissolution by 1840.

Before and after the dissolution of the Federal Republic, the region was characterized by conflict between liberal and conservative factions. The liberals sought to implement reforms inspired by the Enlightenment, while the conservatives aimed to maintain the traditional social order and the influence of the Catholic Church.

Yet, after having been part of the same republic, the young Central American nations were not filled with brotherly love and respect for each other’s sovereignty. Instead, they seemed to have a penchant for invading each other, supporting coups and rebellions in neighboring countries, and generally meddling into each other’s political affairs by military means.

Many of these military interventions were motivated by ideological allegiances, with conservatives attacking a neighboring liberal government and vice versa. Others were simply motivated by the personal affinities of Central American leaders. Regardless of their diverse motivations, Central America hardly saw more than a decade of international peace during the time period going from the 1840s to the early 20th century.

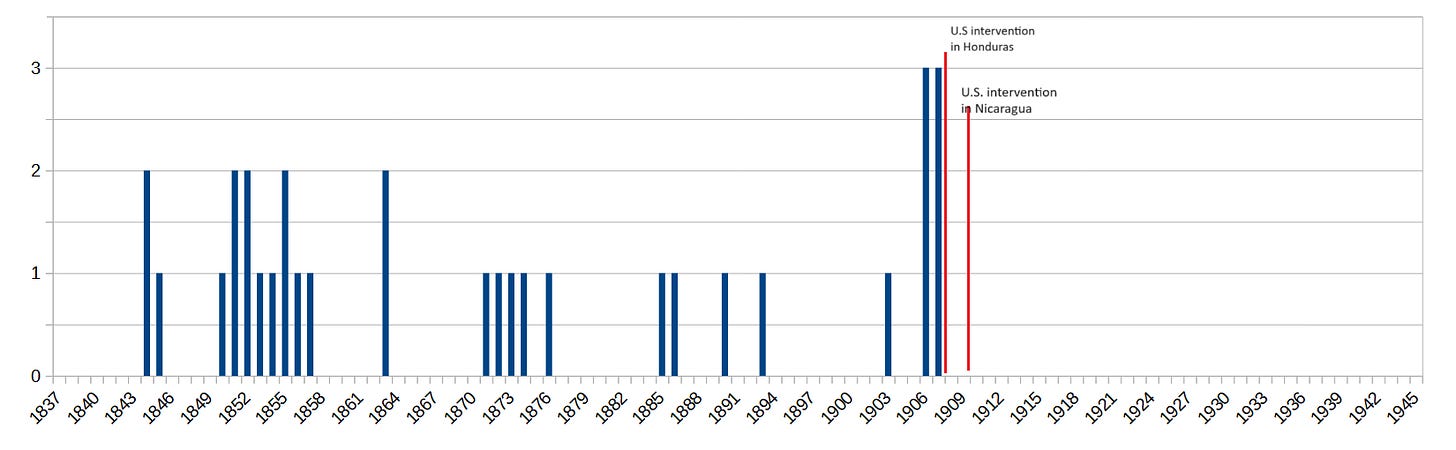

Here’s a chart showing the yearly number of wars, involving at least one Central American country on each side, spanning from 1840 to 19452:

You’ll notice the two red lines I've included in the chart. Those two red lines mark the beginning of American military interventions in Central America3, which intermittently continued for a number of years in Honduras and Nicaragua.

Several of these interventions involved limited military deployments aimed at quelling rebellions, restoring constitutional order, or compelling conflicting parties to negotiate a peaceful settlement to their dispute.

Yet not all American deployments were entirely successful:

On February 28 [1924], a pitched battle took place in [the Honduran port of] La Ceiba between government troops and rebels. Even the presence of the U.S.S. Denver and the landing of a force of United States Marines were unable to prevent widespread looting and arson resulting in over US$2 million in property damage.4

Whether successful or not, American interventions had another goal in addition to promoting internal peace: preventing military interventions by Central American countries into their neighbors' territories.

To achieve this goal the United States would try to dissuade Central American states or factions from conducting incursions into foreign territory:

Department has requested Navy Department to issue orders for an officer and Marines of the Legation Guard in Managua to proceed to territory from which revolutionary activities are directed against Honduras. This action taken at suggestion of President Chamorro. These Marines will be instructed not to enter Honduran territory but to make a thorough investigation of alleged activities by Honduran revolutionists.5

In many instances, the United States didn't need to deploy troops to achieve its goal. Often, the mere threat of intervention was enough to get the job done:

In 1919 it became obvious that [Honduran President] Bertrand would refuse to allow an open election to choose his successor. Such a course of action was opposed by the United States and had little popular support in Honduras...General Rafael López Gutiérrez, took the lead in organizing [liberal] PLH opposition to Bertrand. López Gutiérrez also solicited support from the liberal government of Guatemala and even from the conservative regime in Nicaragua. Bertrand, in turn, sought support from El Salvador. Determined to avoid an international conflict, the United States, after some hesitation, offered to meditate the dispute, hinting to the Honduran president that if he refused the offer, open intervention might follow. Bertrand promptly resigned and left the country.6

This active policy was not limited to military means but also included diplomatic measures, as exemplified by the American sponsorship of the 1907 Central American Treaty of Peace and Friendship7, and the Central American Court of Justice that was established concurrently with the signing of that treaty.

Even after the 1907 treaty fell apart, the U.S. once again convened the five Central American nations and persuaded them to sign a new General Treaty of Peace and Friendship in 19238. This agreement precluded the recognition of any government which may come into power through a coup or revolution.

The thin red lines

Going back to the chart of yearly number of wars in Central America, a clear conclusion can be drawn from that chart. Wars between Central American countries stopped following the U.S. interventions in Honduras and Nicaragua.

There are no more blue bars to the left of those two red lines.

Later in the 20th century, Central American countries did experience new conflicts, such as the Football War in 19699. However, these wars were significantly less frequent than those in the 19th century.

Those later conflicts included the Contra rebellion against Sandinista rule in Nicaragua, where the United States provided support to the rebels operating from Honduran territory, breaking with previous American policy.

Yet, in the early 20th century, whatever you may think of the motivations behind American interventions in Central America, the result of those interventions was peace between Central American nations.

For the purposes of this post, I’m ignoring Panama, which didn’t exist as an independent country until 1903, was not part of the Federal Republic of Central America, and whose only border with another Central American country was barely populated until recently.

Sources are Wikipedia lists, so please take with a grain of salt: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_wars_involving_Nicaragua, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_wars_involving_Costa_Rica, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_wars_involving_Honduras, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_wars_involving_El_Salvador

I decided on using single lines representing the beginning of the periods of intervention in Honduras and Nicaragua. Depending on how you define intervention, I could have depicted a series of lines or a broad red bar spanning multiple years. Regardless of the chosen definition, by the final year of that chart, the United States had not stationed troops in Honduras or Nicaragua for more than a decade.

Tim Merrill, ed. Honduras: A Country Study, https://countrystudies.us/honduras/17.htm

See “The Acting Secretary of State to the Consul in Charge of the Legation in Honduras (Lawton)“, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1920v02/d771

Tim Merrill, ed. Honduras: A Country Study, https://countrystudies.us/honduras/17.htm

“Relations between the United States and Nicaragua, 1898-1916“, Anna I. Powell, https://www.jstor.org/stable/2505819?seq=4. The peace conference that that resulted in the signing of the treaty was also sponsored by Mexico.

Yes, that was an actual war sparked by a football (soccer) match between Honduras and El Salvador.