A comparison of gender equality between Latin America and Orthodox Europe (Part 2)

About the woman mayor next door, and other issues.

This is the second part of my series of posts on gender equality in Latin America, with a particular focus on the differences between Latin America and Orthodox Europe.

In the first part I talked about Female Labor Force Participation (FLFP) and how for Latin American countries data suggests that the higher average income is for a country, the less women feel compelled to work.

Then I tried to check whether measures of political participation of women, usually the percentage of women holding a parliamentary seat, are a good measure for political participation. For that I calculated the percentage of women mayors for each Latin American country, Orthodox European country, and a few other European countries for good measure. I noticed that by this measure Latin American countries still look better - more gender equal - than Orthodox European countries, although almost every country has a much higher percentage of women parliamentarians than of women mayors, suggesting a high political drive to appear more gender equal.

I now have to go back to the subject of women mayors, and comment on a couple of insights that seemed to emerge from the data.

Pobre pero honrado, poor but honest

There’s a Spanish saying that goes más vale ser pobre pero honrado, which can be loosely translated as: I’d rather be poor but honest. That saying likely reflects the usual mistrust of wealth that is so common in Hispanic culture, and even the usual supposition - oftentimes without proof - that wealthy people probably got their wealth by cunning or trickery rather than hard work.

Just like I noticed several countries being rather consistent in their percentages of women mayors compared to women parliamentarians, I also noticed some countries being very inconsistent in that their percentage of parliamentarians, the more visible measure and the more useful when trying to climb international rankings, is several times higher than the percentage of mayors.

And there are some geographical patterns for countries with poor gender equality when measured by women mayors yet much higher gender equality when measured by women parliamentarians. See Europe for example.

In the case of Europe those countries seem to be concentrated in the Western Balkans except for Austria and Belarus. And for Belarus I’m inclined to explain such discrepancy by similar reasons to those for Nicaragua. Also notice how Bosnia is not exactly an Orthodox country, with only about 30% of its population being Orthodox.

And now let’s see Latin America. Red color again indicates five times as much women participation in parliament as in municipalities and pink color four times.

Here the pattern seems to be that Andean South American countries are the ones whose measures of gender equality show a discrepancy: Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru.

These odd countries whether European or Latin American also have on average between 4% and 5% more female participation in parliament than the average for all countries in their region, which seems to confirm my suspicion that political parties in most of them are intentionally trying for them to appear more gender equal than they actually are not by way of getting more women into political posts but getting more women into highly visible political posts.

Going back to the original question of whether Latin Americans have become much more supportive of gender equality than Orthodox Europeans, I think the percentages of women mayors point in the direction of both being less gender equal than they appear to be, while also agreeing with Latin America being more gender equal than Orthodox Europe in this measure.

This would be the end of my analysis (or musings) about women mayors in Orthodox European countries if not for the fact that while glancing over the figures something unexpected happened. I noticed what I think is an interesting pattern related to when and how voters elect women mayors.

You shall not covet your neighbor’s mayor?

In the first post I briefly mentioned in passing that Mexico has a law that vaguely encourages gender parity for municipal candidates, while not so vaguely designating a particular institution (Instituto Nacional Electoral, INE) with powers to object to the candidates presented by political parties if it believes such an intervention promotes gender parity.

This is one possible intervention with the goal of achieving gender equality in political participation. Have an institution that knows better than parties, and consequently knows better than voters, force as much gender equality as it thinks appropriate. And from the point of view of numbers it works. Mexico has 49.8% women parliamentarians and 25.4% women mayors, the highest percentage of women mayors in Latin America after Nicaragua.

Ecuadorian authorities have recently taken the same route, forcing a higher number of women mayors by law, and managed to increase the number to 19% women mayors.

If we want to reach gender equality in political participation what interventions are desirable or permissible to achieve that goal?

I assume that gender equality professionals (did I get the job title right?) worry about this question and about the effectiveness of different interventions, hopefully using a cost-benefit frame of mind when doing so.

Which brings me to what I noticed when looking at the figures and maps for Serbia. Even though I automated as much as possible the process of estimating the number of women mayors for each country, I did take the time to double check some figures and to read about some of the women mayors I found so I could better understand the who, the how and the where of women being elected mayors.

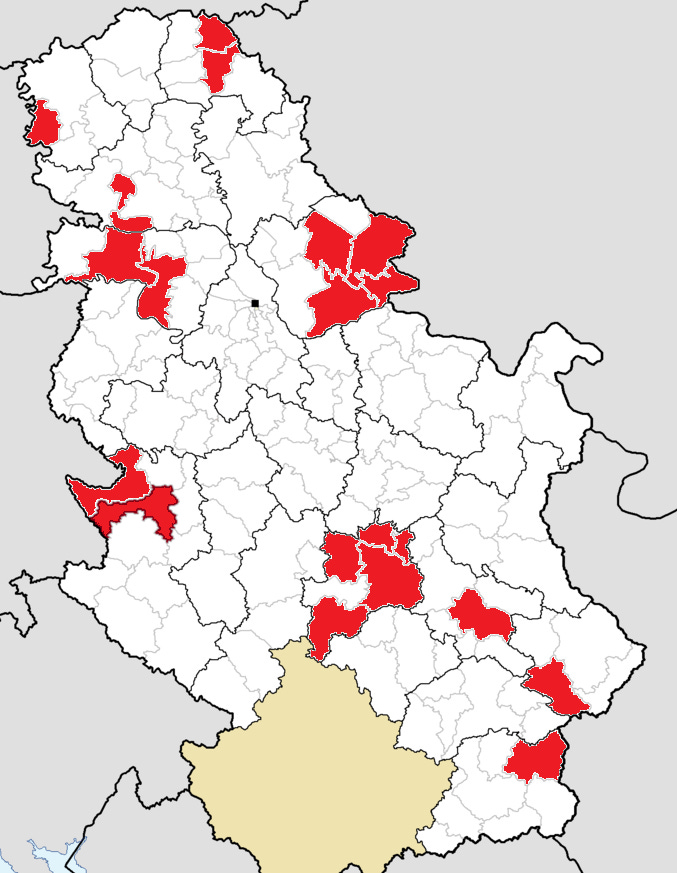

Serbia was particularly interesting to me due to its relatively high percentage of women mayors. But before taking a look at the following map of Serbian municipalities, please accept my apologies for my lack of graphical skills. It’s going to hurt.

The 21 municipalities in red are headed by women mayors. If we assume that women mayors are elected randomly in municipalities of Serbia with a probability of 14.6% for each municipality, then that map seems rather odd.

Of course elections are not random and so it would be interesting to know what factors make more likely the election of a woman, and considering that 17 of those 21 municipalities are bordered by another municipality with a woman mayor it seems to me this points towards one of those factors.

Women participation in politics suffers from path dependence, where levels of female success in an election depend to a large degree in the level of female success of the previous election. The trend is almost always upwards, but it’s easier to go from 20% to 25% in a given period of time, than to go from 10% to 25% in that same period of time.

The fact that most municipalities headed by women in Serbia are adjacent to another municipality (or two, or three, or four) headed by a woman signals that having a neighboring woman mayor is an important factor increasing the chances of electing a woman mayor. If this is a way of breaking a glass ceiling at a municipal level by normalizing the fact that the mayor can be a woman, then it should probably be taken into account when thinking of how to increase women participation in politics.

Does this hold for other countries?

Well, this is a composite map of three northeastern counties of Romania.

11 of 18 municipalities headed by a woman are adjacent to another municipality headed by a woman in those three counties.

And now let’s see a composite map of 7 southeastern counties of Romania.

Notice how besides the large number of red municipalities next to each other (13 out of 26) it also looks like women headed municipalities are much more common in certain regions than in other regions.

And let me end this series of Romanian maps with a composite map of four northwestern counties.

This last map again shows the same patterns. And even though I found one paper in the literature that at least hints at a regional effect of electing women mayors:

Besides, the results unveil that the increase of the portion of women mayors is observed firstly in the south-center part and edge northeastern part of Slovakia. These areas are characterized by high fragmentation of residential structure, low GDP per capita, and higher ethnolinguistic fragmentation. Later, the increase of women’s representation in local governments subsequently continued in the southeastern and southwestern parts of Slovakia.

I did not find anything in the literature describing the neighbor woman mayor effect I just presented. It’s a pitty that I write this Substack anonymously and in the unlikely case that I did find something novel I’ll just get to brag about it to two people over a glass of beer…

A quick note on Serbia before wrapping this up. Apparently Serbian authorities agree with Mexican and Ecuadorian authorities in that forcing higher female participation in politics by law is a good idea, and so they approved a new law in 2021 demanding 40 percent of candidates on electoral lists to be female. This didn’t have much influence in the phenomenon I just described, since only two municipalities headed by women (the two that together form an anvil shape, in the western border of Serbia) participated in the local elections held in 2022.

Maternal mortality ratio and the Adolescent birth rate

Going back to the Gender Inequality Index (GII), two other measures that make up that index are the Maternal mortality ratio and the Adolescent birth rate. I agree with the UNDP in that they are important measures of female well-being and so have an impact on gender equality.

In both of these measures Orthodox Europe fares better than Latin America. For adolescent birth its rate is 19.6 (births per 1,000 women ages 15–19) compared to 57.7 for Latin America, while for maternal mortality its ratio is 11.4 deaths per 100,000 live births vs 66.8 for Latin America.

In the case of adolescent birth it probably affects the rate of households headed by single mothers, an effect that also has several other downstream effects. More on that later.

And in the case of maternal mortality, only the two countries with the lowest maternal mortality in Latin America (Chile and Uruguay) are in the same range as Orthodox European countries (13 deaths and 17). I can’t think of anything that would explain those high rates of maternal mortality that is not related to material conditions (health spending) and the quality of medical personnel.

Here it gets tricky to disentangle what are the effects of poverty or under-development on gender equality from the effects of culture or legal frameworks that might make a country more or less gender equal. Just like FLFP can be negatively affected by the general level of wages in a country, and the solution to low wages seems to be to just get richer, it can also be positively affected by the desire of women for professional fulfillment, higher status and avoidance of boredom.

If the way to reduce maternal mortality and also to increase FLFP is to get richer, then that presents a difficult problem for people and institutions concerned about gender equality. Trying to change the culture of country X for a more gender equal culture will only get you so far. Trying to change the legal framework through more gender equal laws and regulations will only get you so far. Poor countries might progress a great deal, but eventually there’s going to be a point where poor culturally-gender-egalitarian countries will not be able to close the gender equality gap with rich culturally-gender-egalitarian countries. And closing that gap is an economic problem, so it’s outside the focus of people and institutions concerned about gender equality.

Should we care if that gap persists? Should women wish professional fulfillment? Should they care if they can afford all their needs thanks to their hard earned money or thanks to the money earned by their spouse?

My point is that the Gender Inequality Index and all other similar indexes or rankings are making certain assumptions about what women want and what makes them feel good and safe and happy. Some of those assumptions strike me as very reasonable, as I cannot imagine a woman that enjoys domestic violence or doesn’t mind the possibility of being assaulted. But women belonging to different cultures might have different values and preferences, and current assumptions of people and institutions concerned about gender equality may not be valid for certain countries or regions of the world.

If you felt a bit uncomfortable when I said thanks to the money earned by their spouse, and you thought: what about single women and single mothers? then you’re probably a very empathic person and I personally think you should feel good about it.

Like I mentioned before, the adolescent birth rate for Latin America is 57.7 births per 1,000 women ages 15–19, the second highest for any region of the world after Sub-Saharan Africa. And a large part of those adolescent mothers will end up being single mothers.

I checked the United Nations Database on Household Size and Composition in order to better understand the structure of households in Latin America, and it confirms that Latin America has a high rate of single mother households, higher than all other regions of the world except for Eastern Africa and the Caribbean.

I can’t be certain about the exact rate because the Database uses five different sources (DHS, DYB, IPUMS, MICS, LFS) which don’t necessarily agree in their methodologies and in many cases the data was collected and compiled more than 10 years ago. That being said, for Latin America it appears that 9.8% to 9.9% of households are single mother households.

And the rate for Western Europe appears to be 6.3% to 6.7% of single mother households. There’s a difference of around 3.3 to 3.4 percentage points between the rates of both regions.

If I use only one source (DYB) in order to be more consistent yet at the cost of limiting the sample (only 12 countries for Western Europe and only 8 Latin American countries), then the rate for Latin America is 10.70% and for Western Europe it’s 6.56%, with a 4.14 percentage point difference.

Let’s assume the real difference is 3.7 percentage points. And let’s say those 3.7 percentage points represent 3% of women of working age (some households will have more than one woman of working age). If that 3% of women of working age are forced to work in order to support their family but only 1.5% of them would work if they were part of a household with two or more adults, then you could say that FLFP for Latin America is higher, by a small amount yet higher, than it would be if single mother households were not so common. Or more precisely if single mother households were just as common as in Western Europe.

I know 1.5% is a small difference, and given how patchy the data from the Database on Household Size and Composition is you should take this with a big grain of salt. But I thought it was important to make this point in case someone thought my case for Latin American women having a lower compulsion or desire to work than women from higher FLFP countries was not strong enough.

Next time I’ll preface this kind of not so certain small effect analysis with something like: please skip the next few paragraphs if you are not interested in small effects. I promise.

I intend to continue this series of posts on gender equality in Latin America with a third and hopefully last post on this issue.

And if you’ve liked this series of posts so far, please subscribe.