Is the UK a zombie nation?

The second part of my questioning of the British decline narrative. A response to Samuel McIlhagga.

I didn’t mention this in my previous post about the supposed decline of Britain, but my main motivation for writing that post was as a response to Razib Khan’s podcast with Samuel McIlhagga titled Samuel McIlhagga: the UK as a zombie nation.

I haven’t read each and every article or listened to each and every podcast published in the last few years about the supposed British decline, and since I’m too lazy to do so now, I’ll just focus on that podcast and also on the article published by McIlhagga in Palladium Magazine and try to refute a few particular points made by him. Not that they are major points but I do think they contribute to the perception of British decline.

At the 9 minute mark of that podcast McIlhagga says:

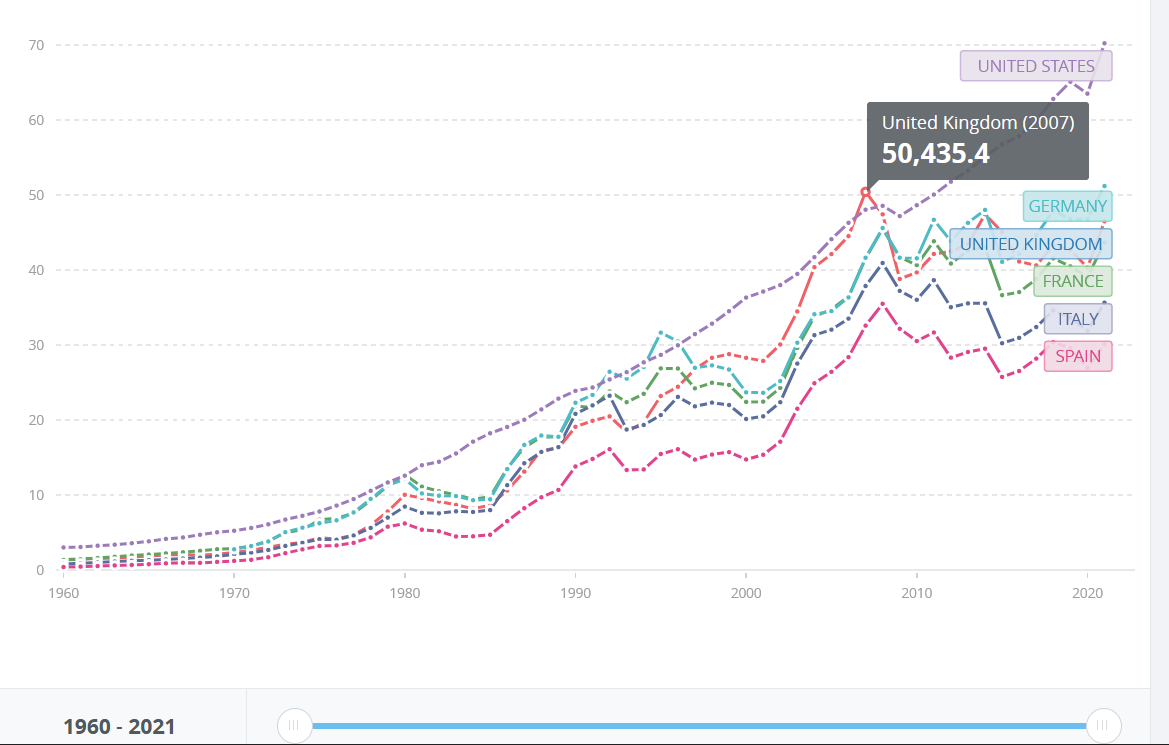

I think there was a point in 2009 when we had a higher GDP per capita… maybe it was 2007, than the US

He’s referring to this:

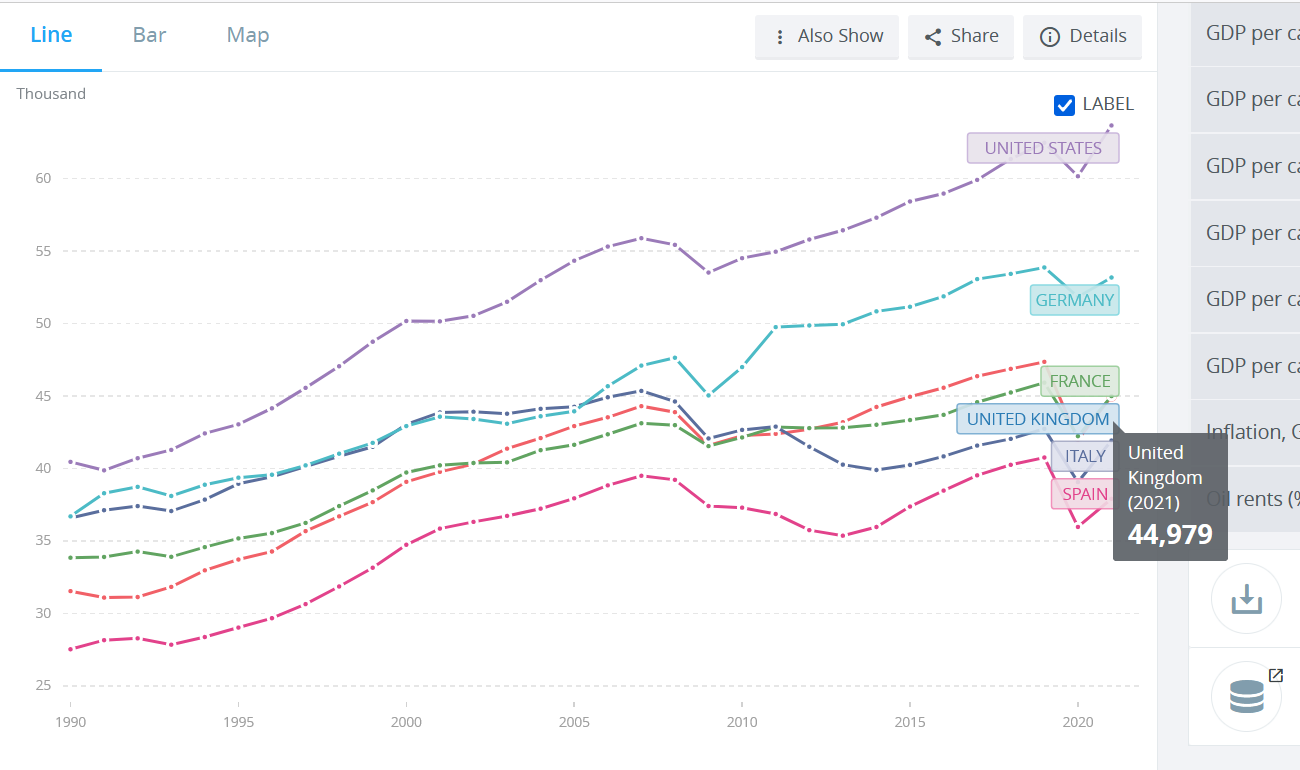

But as you can see by comparing it to the graph in my previous post, that was just the product of using the wrong measure, GDP per capita measured in British Pounds without regard for the exchange rate of those British Pounds against other currencies, at a very particular time. This graph uses the more appropriate measure of GDP per capita PPP (Purchasing Power Parity) in order to eliminate the differences in price levels between countries:

I don’t think any of the commenters making the case for British decline would argue that per capita product in Britain diminished more than 20% in two years just because this graph also seems to imply so, when measuring GDP in US dollars.

And from the Palladium article:

The exact purpose of elite education was, I discovered, a topic of surprising disagreement. James Schneider, once Director of Strategic Communications for former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, believed that the British state faces exogenous forces outside its control. Because of this, educational reforms cannot make it more effective.

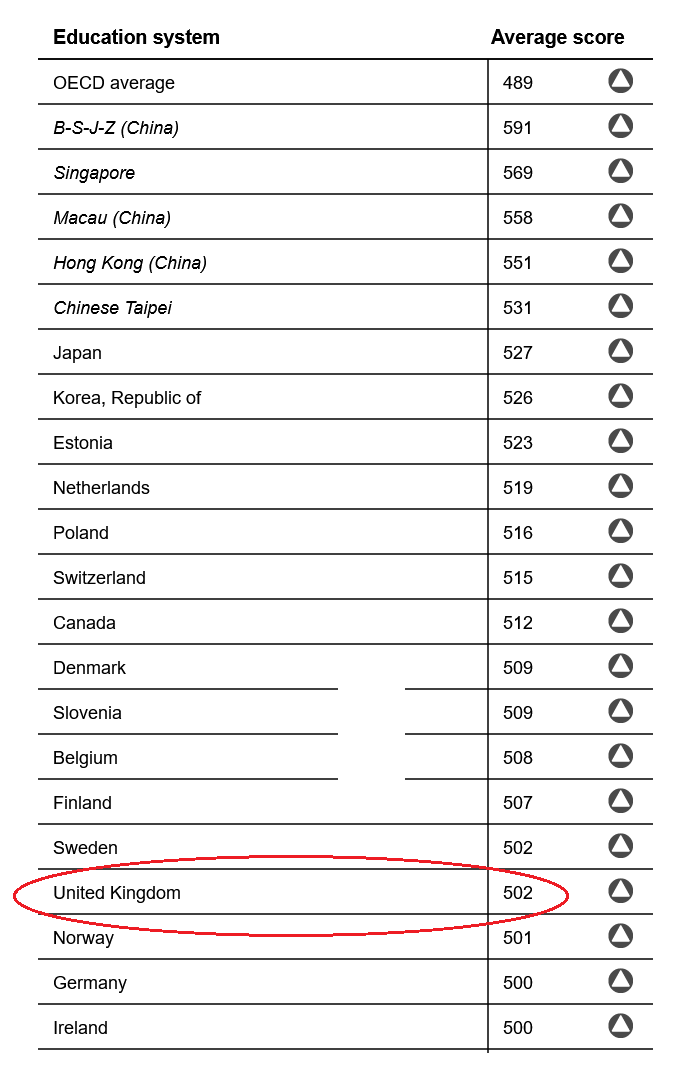

But the UK seems to be doing very well when compared to other countries judging by its results in the international PISA tests. The UK is number 18 out of 78 countries in math, and number 14 out of 78 in reading and science.

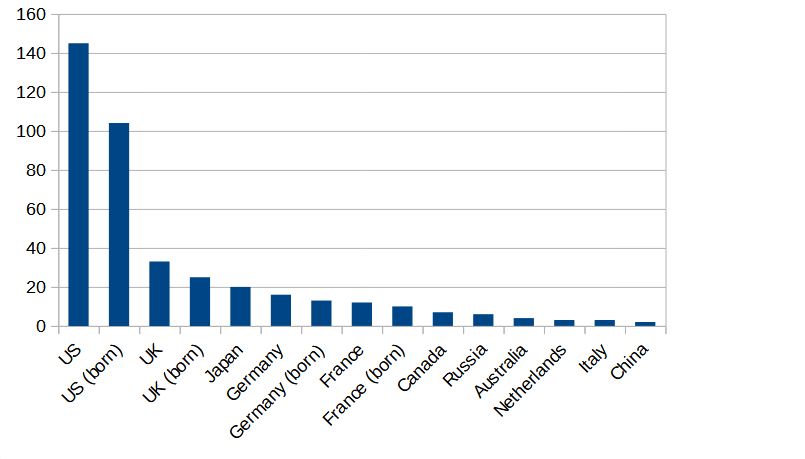

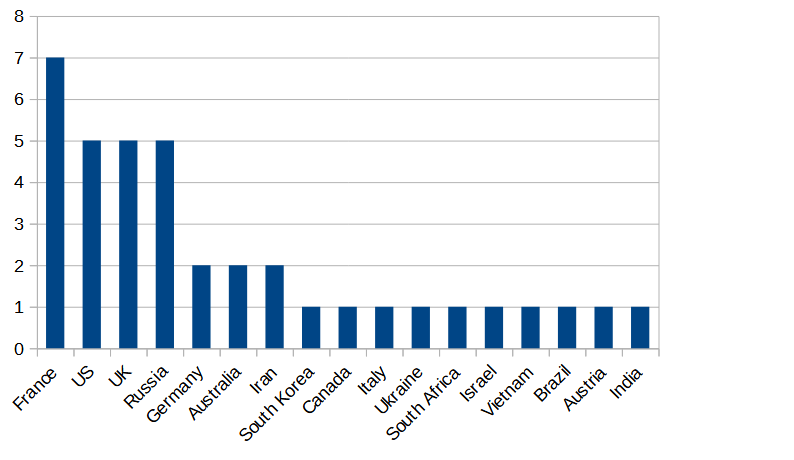

And when it comes to research the outcomes of UK researchers seem to be higher than those of peers countries when measured by the number of winners of the most prestigious prizes in science, science Nobel prizes and Fields medals:

As a corollary to the first graph of science Nobel prize winners by country, the UK seems to also be very good at attracting good researchers - compare UK and UK (born) bars.

Going back to the podcast, at the 53 minute mark Samuel McIlhagga says:

some of the worst outcomes in economics, inequality, productivity and innovation in all of Western Europe

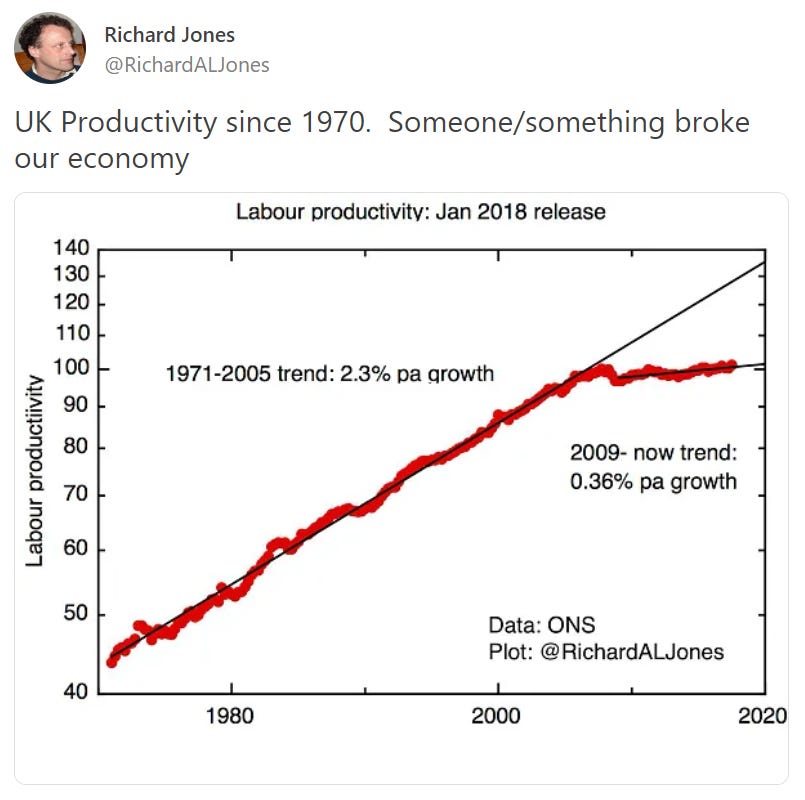

And the “collapse” in productivity is also mentioned by Adam Tooze (citing Richard Jones):

The collapse in real wage growth mirrors trends in productivity, which again show a sharp break with previous experience.

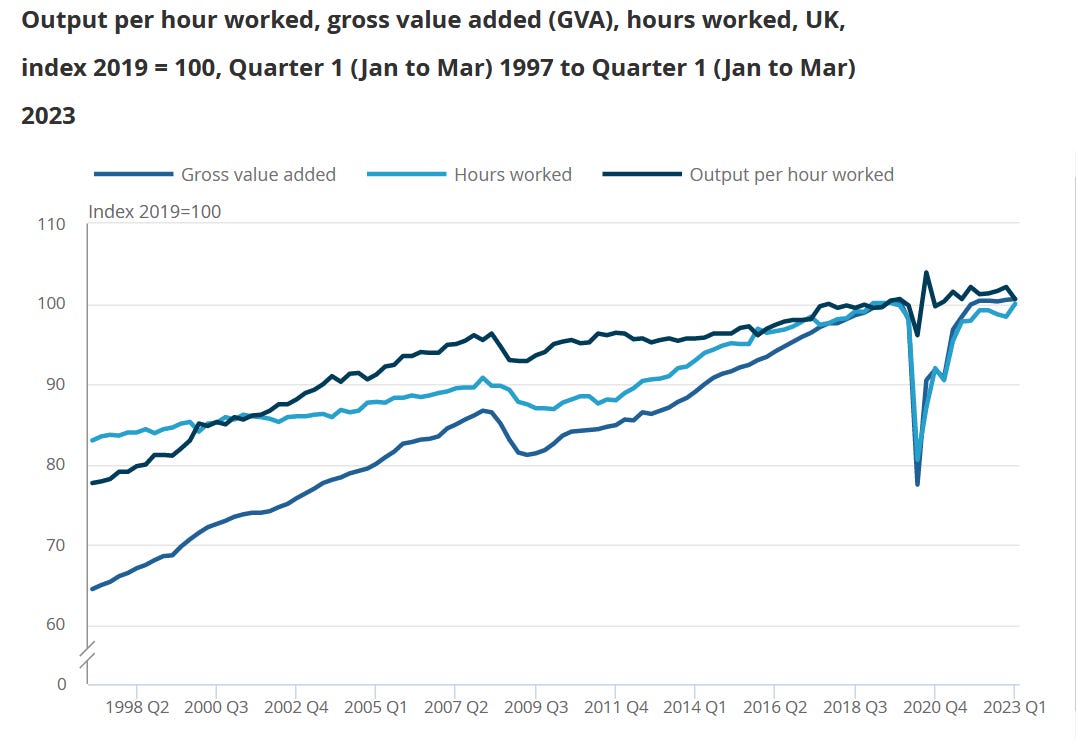

But a closer look at that graph of labor productivity reveals that the scale is not linear. This is the correct graph in order to see if productivity is collapsing in the UK:

Which shows that productivity in the UK has been growing at a slower pace than in the 00’s but is still growing.

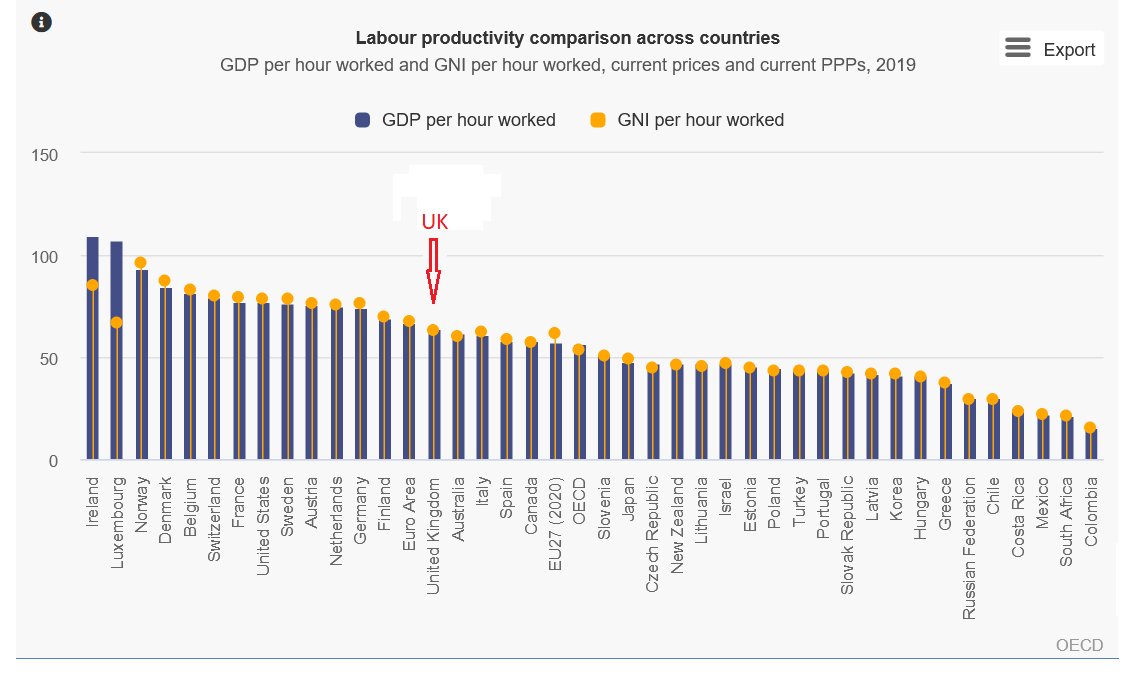

And how does UK productivity compare to other “developed” countries?

That is not stellar, most Northern European countries have higher productivity than the UK, but not horrible either. The UK’s productivity is higher than the OECD average, higher than the EU27 average and higher than the productivity of Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

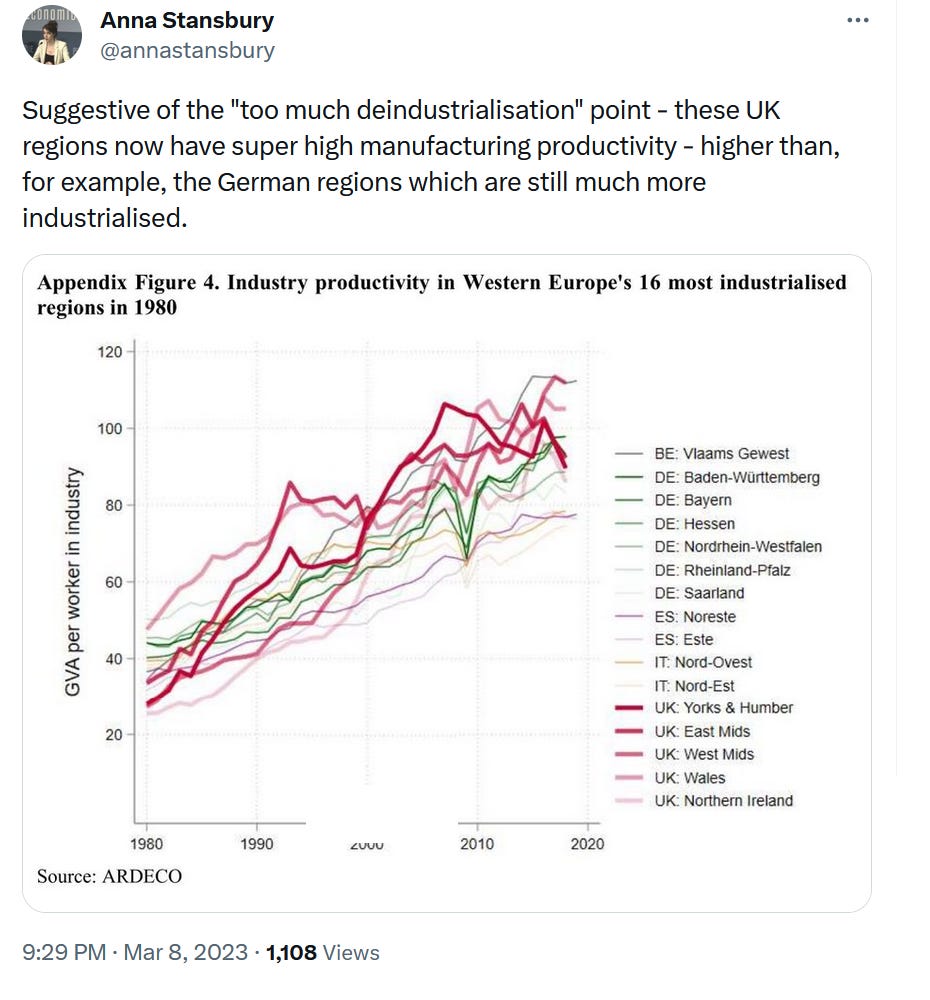

A common objection to that seems to be that high productivity in the UK is concentrated in the financial industry. But if that is the case, this should not happen:

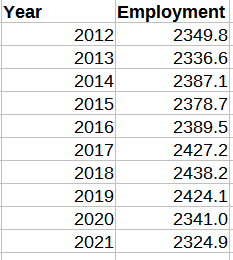

Maybe British manufacturing has high productivity but employment in manufacturing is collapsing?

You can see employment growing at a nice clip from 2012 to 2019, even after the Brexit referendum, and then the unsurprising drop in employment due to Covid-19. We will have to wait until ONS publishes the data for 2022 in order to know if manufacturing employment has completely recovered from Covid-19 or not.

None of these points completely refutes the idea of British decline, just like none of the points made by those who advance that idea taken separately proves their narrative. And that is part of the problem that I see with that narrative. If someone states 20 different arguments all seeming to point in the direction of narrative X over and over again, and you only read a about a clear, data supported rebuttal to 1 of those 20 arguments, then… X must still be true, right?

Well, no. Each and everyone of those arguments should be evaluated separately, probed, and refuted if the data doesn’t support it. And if the picture that emerges after that process is the UK has a problem in the domain of area Y instead of the UK is in serious general decline that would be a very different picture.